Four and a half years ago, I was working at a startup music website that never ended up launching; the parent company decided that it wasn't worth the investment and laid all of us off. But for months, we went into work in a gleaming midtown office every day, concocting possible recurring features and tinkering with possible editorial voices and figuring out the eventual identity of a site that never got a chance to exist. One day, our editor called all of us to the table at the center of our office and decided to run a drill. Here was the situation: David Bowie had died that morning of a heart attack in his Manhattan apartment. Our editor laid out the situation and then barked out assigments: One of us would write the comprehensive obit, one would get on the phone and try to get quotes from his contemporaries, one would set up shop outside his building. I'd never really considered the possibility of a post-Bowie world, but it suddenly became a lot more tangible. Here was an aging icon, deep into his 60s, who had lived hard and had, from all appearances, faded into retirement forever, content to putter around New York and to show up at the Bowery Ballroom every time a mid-'00s indie buzz band made its inaugural NYC appearance. He was, from all appearances, satisfied with his life's work and enjoying his dotage, and rumors about his failing health started to circulate not long after. So it's pretty stunning to hear a 66-year-old Bowie, refreshed and vigorous, preening his way through a happy surprise of a new album. He didn't owe us anything, and he had nothing left to prove, but he's given us another characteristically self-aware and adventurous piece of work, the latest in a long, long line of them.

The first time Tony Visconti produced a David Bowie album was 44 years ago, and that album was Space Oddity. Visconti has done a ton of work with Bowie over the years, and he understands Bowie's aesthetic -- or his panoply of aesthetics -- better than any other prospective collaborator would. Visconti also co-produced Heathen and Reality, the generally unremarkable 2002 and 2003 albums that, most of us assumed, marked the end of Bowie's career as an active recording entity. I don't remember much about those albums, except that they sounded tired and inessential. And they came at the end of a period when Bowie, who spent years adjusting his presence a few steps ahead of mass culture at large, seemed to be playing catchup, seizing on jungle beats or Trent Reznor collaborations during those things' mid-'90s heyday. One thing about The Next Day: It exists entirely within the world of Bowie's back catalog, especially his late-'70s Berlin trilogy. The guitars are grim and dry and spartan, the dynamics spacious and cold, the rhythms sharp and ungainly. Occasionally, you'll hear flashes of astral flower-child Bowie or ripsnort glam-stomp Bowie or impressively pompadoured soul-funk Bowie. None of it nods toward any recent trends that can't be traced back to him, and yet it sounds completely of-the-moment anyway, largely because Bowie's own work has seeped so completely into music as it exists in 2013. Bowie is not the only person these days recording music that sounds a bit like Low.

Given recent chatter about his health, it's important to note that Bowie's voice is pretty much the same mannered and bitchy ice-wail that it's always been. It's a bit deeper in the mix this time around, but he's not audibly straining to hit notes or holding his delivery back. And it's also telling just how hard some of it sounds. "Dirty Boys" is a sputtering lurch with a glorious hook. The whoo!s and yeah!s at the end of "Valentine's Day" feel entirely earned. Album closer "Heat" sounds vaguely like recent Scott Walker, if he was more interested in melody than in breaking your head. And some of the melodic moments here -- the bridge on "I'd Rather Be High," the clipped and nervy verses on "Dancing Out In Space," the swelling-up choir at the end of "You Feel So Lonely You Could Die" -- serve to remind that Bowie was always a pop craftsman as much as he was an innovator. I can say firsthand that "The Stars (Are Out Tonight)" sounds good on the actual radio, removed completely from the context of the album or the internet.

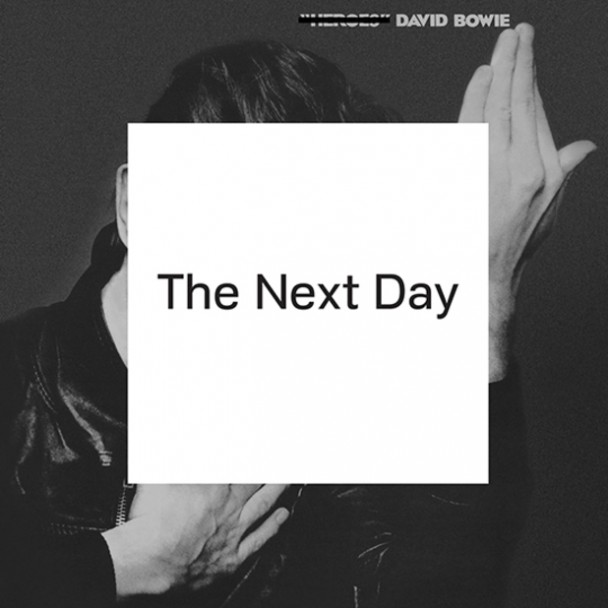

Already, reviews are circulating that call The Next Day one of Bowie's best albums. That's patently absurd. This is the guy who made Ziggy Stardust and Diamond Dogs and Young Americans and Low and Heroes, the cover of which suffers a bit of a subway-poster disfiguring to become the cover of this one. On The Next Day, the songs are too diffuse for that, the ideas not quite focused enough. The album doesn't carry the sense that Bowie is knowingly reshaping the world around him. For all its spartan sonics, it radiates the warmth of an old man happily flipping through photos of his younger self. But The Next Day does feel like a fully developed David Bowie vision, in a way that his past handful of albums don't. It's not a pantheon album, but it's far from an afterthought.

The Next Day is out 3/12 on Columbia. Stream it here.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]