First emerging in the early '80s, They Might Be Giants were compelling, confounding, and arguably without precedent. They remain, 30 years after the fact, relics of a period in which underground rock's largely regional character incubated success stories from gifted weirdos across the country. Just as sunbaked desert days helped to produce the druggy haze of the Meat Puppets' best work, and the Minutemen were products of Southern California's multi-cultural melting pot of influences, TMBG, with their remarkable combination of free-associative intellectual constructs, indelible hooks, and withering humor always felt like a particularly deranged MIT experiment. Something like a couple of very large brains placed in a blender with a handful of Big Star records, some uniquely tasteless exploitation films, and the entire canon of Russian literature. Early TMBG records are so heavily referential with respect to the musical culture that it can feel a bit like an off-brand, aural actualization of the album art for Sgt. Pepper's. On the first record alone namechecks run the gamut from Menudo to the Eurhythmics to Elvis Presley to Marvin Gaye and Phil Ochs, to name but a few. Much in the same manner that Quentin Tarantino has made a career out of re-imagining and reordering the cultural space to create new mythologies, TMBG's brilliance lies in their polymath's knack for taking in every manner of influence, and eventually bending it to the will of their very particular, and very perverse, imaginations.

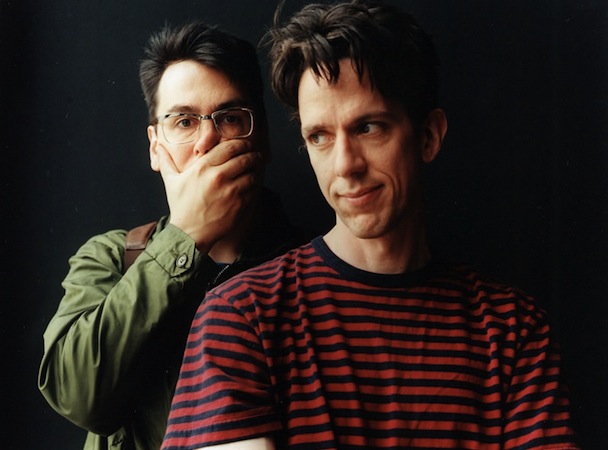

Such a long-running success story (and their two excellent recent albums make it clear the band is as creatively vital as ever) must reflect something inspired in the initial composition of the group. The two Johns who functionally are They Might Be Giants -- John Linnell and John Flansburgh -- are that rare coupling of creative compatriots who are close enough in aesthetic tendencies to tolerate a three-decade partnership, but far enough away that their collaborations still crackle with the intensity of two distinct visions struggling to alchemize into one. In the oversimplified shorthand, Linnell is more of the straightforward pop guy, while Flansburgh is perhaps slightly more inclined towards the experimental and digressive. But crucially, either one can write an unforgettable pop tune at any time, and either can get weird and freak out a whole city block in the span of two minutes. TMBG has every club in the bag, and probably some that aren't even sanctioned.

As many of their early peers have waxed and waned in terms of popularity and influence, or retired, or died, or possibly worse, They Might Be Giants has retained a nearly startling level of popularity amongst both its rank and file fan base and an influential community of fellow musicians who perceive them as both idol and ongoing inspiration. The excellence of the band's catalog aside, this may be partially attributable to the savant-like, pre-internet cognizance TMBG seemed to possess about fan outreach through asymmetrical means. Their habit of tacking flexi-discs to random telephone poles as well as their legendary "Dial-A-Song" series, were brilliant early realizations of the inherent limitations of the rote label/publicist/ad buy approach to promoting records. In this regard, they were brilliant at symbolically working the room -- actually connecting with their fan base on an intimate and populist level -- grasping the notion that reliability and access were ultimately far more charming and likable than the million mile remove of pompous rock stars expressing their bloated selves, willful and indignant, to borrow a phrase from fellow traveler Dan Bejar. So now we take this great, long running band and adjudicate just ten songs that might qualify as their best. Eight might be enough to fill your life with love, but ten is not remotely enough to cover the best of They Might Be Giants. Mistakes will be made, children will be neglected. But at least here is an overview of one of the greatest bands that ever dared to be strange, and vice versa.

10. "Judy Is Your Viet Nam" (from Join Us, 2011)

During the relentlessly vituperative minute and half during which "Judy Is Your Vietnam" unfolds, Flansburgh paints an unmistakable portrait of an ostensibly desirable femme fatale who in fact, for the love of god, must be avoided at every cost. Over an early Who-style rave up, the lyrics are a master class in efficiency. By the time you get through the opening couplet "You met Judy in the '90s/ She threw parties for magazines," a kind of dread has welled up in the listener. Yes … we too may have met someone like Judy. (Or did we actually meet JUDY???) From there, things only devolve -- Judy is an aging bohemian with a revolving cast of roommates and very little regard for the sanctities of romantic fidelity. She is, memorably "the storm before the calm." This is "Positively 4th Street" brilliantly cut in half -- a pivotal moment and a crushing critique.

9. "They'll Need A Crane" (from Lincoln, 1988)

They Might Be Giants have a track record of writing great songs about relationships that have gone sour, but they are usually viewed through something of a comical, occasionally cynical lens. "They'll Need A Crane" stands out in this regard as a surprising outlier because while it has most of the hallmarks of a TMBG classic (wonderful hooks, sharp lyrics, and an impressively short run time) it stands out as being one of the most simply poignant, saddest songs that they have written. "They'll Need A Crane" tells the story of Lad and Gal, two broken souls and their on-the-rocks marriage. Everyone and everything is beyond repair for these two and so the sensible thing is to just tear the whole sorry lot down, all and sundry, completely. It's fucking grim. It shouldn't work as a fast power-pop song. And yet, TMBG managed to nimbly walk the tightrope, splitting the difference at the molecular level between light and dark, making one of the most effective meditations on love lost to ever occupy 2:33 of a record, that manages to get the point across with time to spare for a purely magnificent bridge that captures everything about the band's genius songwriting abilities.

8. "Working Undercover For The Man" (from Mink Car, 2001)

One of TMBG's ingenious tropes is to turn their gaze inward and write songs about bands and the experience of being in a band, either real or imagined. This has been adroitly executed in their delightful, perhaps-fully-manufactured-from-whole-cloth meditation on being in the Replacements, "We're The Replacements," which more or less narrows down that particular experience to moving and locating equipment, finding Tommy Stinson, and having a party. Other examples include "The Mesopotamians", about a fake, but fully realized group that has been around since time immemorial, the aspirational tale of wanna-be drummer "Dr. Worm," and "They Got Lost," a plausibly factual accounting of TMBG getting lost en route to a performance. "Working Undercover For The Man" follows boldly and originally in this tradition, telling the story of a covert agent posing as a rock star as part of an intelligence-gathering mission. Amidst an inspired Flansburgh vocal and lilting horn/synth arrangement, the song makes being a rock and roller actually seem pretty dull. "I've been working hard/ trying to sing and play guitar … paid to fake it in a traveling band/ and I'm working undercover for the man", he tells us. Only They Might Be Giants would think to strip away all of the glamour and mystique of rock and roll quite this way. The narrator here doesn't want to come to your town to help you party down, he's just doing this to tell on people.

7. "XTC Vs. Adam Ant" (from Factory Showroom, 1996 )

No one, but no one, other than TMBG would have ever considered the proposition of a song pitting XTC versus Adam Ant in an epic battle to see who would capture the future of music. For one thing, as legitimately replete with charm as both bands are, neither was ever exactly on the brink of becoming the next Zeppelin. Future historians would not know that from the account given here, where over a bombastic rock attack, the band posits the non-existent XTC/Ant imbroglio as the ultimate contest between content and form. It is a deliriously insane instance of TMBG's cheerful way with reinventing culture as they might have enjoyed it better. Also amusing: despite the colossal, wars-of-Armageddon nature of the song's presentation, absolutely no one can decide who wins. Flansburgh seems apocalyptically driven to render the narrative, but also allows that neither side is wrong. Even the singer from Bow Wow Wow can't make up her mind.

6. "Meet James Ensor" (from John Henry, 1994)

The two Johns have an uncanny knack for putting together truly catchy songs that have the added benefit of being educational. This might be best evidenced by their run of excellent children's records, which are loaded for bear with tracks where you might actually learn something. They've also had storied success teaching their adult audience about James K. Polk (the 11th president) or more recently in their song "Tesla" from Nanobots, which is about the inventor Nikola Tesla (It remains to be seen if they will ever write an homage to the band Tesla). "Meet James Ensor" fits neatly into the category of great TMBG songs that lend itself to a "teachable moment." It is a minute and a half potted history of the Belgian expressionist painter James Ensor, his life and artistic style. It's sprightly and charming, with echoes of Jonathan Richman's previous fine art appreciations, "Pablo Picasso" and "Vincent Van Gogh." There is a kind of confederacy between under-appreciated artists through time and viewing themselves on a continuum, and the best of them never stop enthusiastically testifying on behalf of their cohort.

5. "Birdhouse In Your Soul" (from Flood, 1990)

The quizzical but undeniably triumphant first single from TMBG's major label debut Flood is a straight pop gem with a vaguely subversive agenda. By any standards "Birdhouse" was an oddity. When its video first debuted on regular rotation on MTV, it is fair to say that nothing of the kind had really existed on the network. As a song, it is a real beauty, an amalgam of the comic, baroque, and deeply considered. It anticipated the more whimsical clips from Yo La Tengo and Weezer and set a standard for a new, less self-consciously masculine version of what was then known (unfortunately) as "modern rock." Above all, it was a great tune with a great video and a highwater mark of early-'90s achievement.

4. "Can't Keep Johnny Down" (from Join Us, 2011)

The lead track from Join Us is a reminder that TMBG exists on a unique plane, someplace between audience friendly and fully alienating. Set to one of their most fetching melodies ever, "Can't Keep Johnny Down" possesses all of the hallmarks of an easy introduction into a seemingly innocuous power pop record. That is until the lyrics kick in -- bringing to bear an environment of outsized fear and paranoia that could only yield the world historic great opening salvo: "Outnumbered a million to one/ All the dicks in this dick town/ Can't keep Johnny down." You'd think it couldn't get better from there, but by god, it does. We won't ruin the surprise for the uninitiated, but rest assured that you will not spend a better three minutes this side of a Chicago Blackhawks power play.

3. "Don't Let's Start" (from They Might Be Giants, 1986)

The herky jerky pop gem from TMBG's self-titled 1986 debut helped set the template for the band's patented blend of synth driven hooks, killer melodies and oddly dyspeptic lyrics, which often create a surreal and disorienting sense of disjunction when juxtaposed alongside their seemingly sunny delivery. "No one in the world ever gets what they want/ and that is beautiful," Linnell sings, conjuring a sentiment as dark and existentially cold as any to be found on a Voidoids record. The difference here is that TMBG doesn't sound angry or alienated or even sarcastic -- they sound absolutely tickled. This senseless, empty, meaningless world is truly their oyster. "Don't Let's Start" is a masterful early instance of the kind of difficult to metabolize subversiveness that has always made the band polarizing, but which also makes them great.

2. "I Palindrome I" (from Apollo 18, 1992)

This sublime single from 1992's Apollo 18 is perhaps one of the best examples of the band's polymath minds working overtime. At first blush, it's a captivating pop song with the usual mordant sentiment that is the two Johns' stock-in-trade, with the winning opening lyric, "Someday mother will die and I'll get the money," and the fun, if elliptical chorus, "You son of a bitch, I palindrome I." But closer examination of the lyrics reveal that Flansburgh and Linnell have actually peppered the entire song with palindromes throughout -- Flansburgh's backing vocals are more or less all palindromes, the nonsensical "Manonam" and the somewhat sensical "Egad a base tone denotes a bad age," and the soaring, awesome bridge is one gigantic palindrome. Also, the song's 2:22 runtime might not be an accident. It is a frustratingly clever song that cannot help but get its hooks (and there are many) into you.

1. "Ana Ng" (from Lincoln, 1988)

Perhaps the finest distillation of all of the band's manifold merits, "Ana Ng" possesses all of the infectious dexterity of "Don't Let's Start" but manages to broaden its narrative purview in nearly panoramic ways. Part love song, part war story, and partly a critique of the human condition, this is TMBG at the intimidating height of their intellectual powers, cranking out what is essentially rock and roll's own poignant take on For Whom The Bell Tolls in 3:22 of astoundingly efficient storytelling.