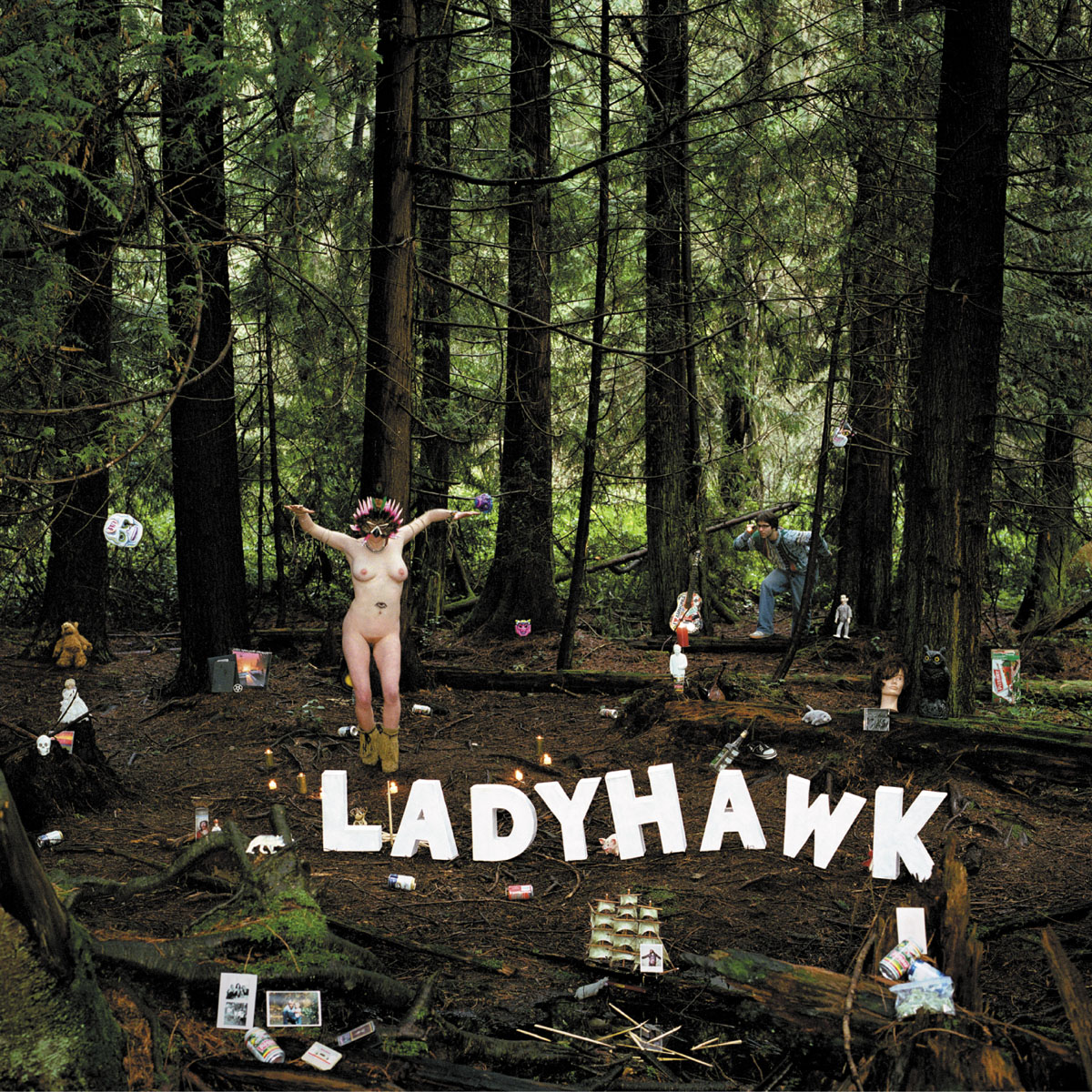

In 2006, Vancouver band Ladyhawk released their self-titled debut album. There are a lot of ways you could describe it: beer-soaked, stoney, depressed, brawny, reminiscent of Crazy Horse. At various points in my writing career, I've described it as all of these, plus a lot more things that never quite nailed what the band was all about.

Ladyhawk shared a label with Jason Molina, but there was more to that kinship.

Singer Duffy Driediger's voice is as much of a force as Molina's, but where Molina's would crack under the weight of the world, Driediger was raging against it. Drinking beers, smoking joints, writing songs about lost loves, being scared and wandering the Vancouver streets wasted, weaving home through wet winter nights. Each Ladyhawk album adds more to this mythology/reality thing Driediger had going. As they moved on to the angrily hallucinogenic EP Fight For Anarchy, through Shots, an album that not-so-subtly grappled with the existence of god, and then even further into various side projects that belied a love of power pop and always, forever, Silkworm. But that debut feels like the most concise version of a world that Driediger created and then dedicated his career to exploring.

"Came In Brave" finds Driediger attempting to go out before realizing it's too much for him to deal with, heading home to get high on his back porch surrounded by empty beer cans and cigarette butts, wishing he had the guts to say what he wanted to say to a girl. It's a pretty universal feeling and it's a pretty quick and easy way to define the mindset that Driediger wrote from on that first album: not a young kid anymore, but not a fully matured adult either. Driediger is writing about the specific purgatory of your 20s, also known as the time when you're meant to figure out a whole lot of terrible things without much preparation or help or warning.

The first time I saw Ladyhawk play was during CMJ at the now defunct Lower East Side club Tonic. I don't even remember how full the room was, or what I did after, or what I was drinking. I just remember that I immediately felt, even at that nascent stage in my writing career, that Ladyhawk had nailed a specific sort of malaise -- a 20-something aimlessness that fell somewhere between despairing about despair and a love of wallowing. It made me feel okay about being unsure about just about everything in my entire life.

Being a relatively young music writer at the time, I got a lot of questions about if my life was like Almost Famous. The short answer was "no," the long answer was also "no." In that movie, Patrick Fugit plays William Miller, himself a stand-in for Cameron Crowe, who directed the movie that was loosely based on his own experiences. Fugit as Miller hangs out with a fictional band, is at first impressed by the world of rockstardom, then discovers it's actually kind of shitty and terrible. He learns about himself and the band learns about themselves and everyone goes home sort of happy, but older, exhausted and possibly in danger of experiencing acid flashbacks.

When I would go hang out with bands for stories, it didn't destroy any illusions, because my illusions mostly weren't there in the first place. The internet made everyone seem pretty regular (except Kanye West and maybe also DJ Khaled), so Ladyhawk, a band that made a point of reminding you, song after song, that they were regular guys with the exact same problems that you had -- the exact same money worries and fears and issues with reaching some imaginary standard that didn't exist -- didn't really strike me as the sort of people that would provide some great insight into my future through the lens of their fame.

I flew to Vancouver in the middle of winter and spent three wet days with the band, lurking bars, going to concerts, eating Chinese food, visiting their frigid practice space. I couldn't really keep up, as much as I wanted to. After a marathon beer drinking session, I got the hiccups so bad that, about an hour before last call, I had to go back to my hotel to lay down so my stomach would stop feeling like it was punching itself from the inside. Not that glamorous.

For their part, the band couldn't have been nicer about it. They were just hiccups! But what was I supposed to do about it? The story that I came back with was decent, but not great. It ended up being sort of about friendship and sort of about being in a band that was really great but not as universally loved as they should be. Being a Ladyhawk fan is like being in a cult. I don't actually know anyone that feels mediocre about their music, just people that really love it, or don't care to know about it at all. But for those that loved it, Driediger illustrated something important in his lyrics: being down is okay. Wallowing -- in moderation -- is totally fine if you can get something out of it. In his case, he wrote these heartbreakingly strong songs about regular life, other people write poems or books or make sculptures or are chefs or whatever. It's not really the point. The point is that Driediger never glorified these moments. It was never about impressing anyone, but it wasn't really about therapy either. It was about ramshackle rock songs that could barely support themselves, often falling apart just as the guitar solo came into play.

"Advice" begins with the lyrics: "Don't take it personal when they forget about you," and as depressing as that sentiment might seem, it's also pretty true. You'll get forgotten. I'll get forgotten. The Almost Famous kid? He gets forgotten by the band like 20 times within the two hour period of the film! It's what allows him to get a good story and learn about himself. It's also what made this album so great. Driediger makes it pretty clear: nothing matters, except when everything matters, which is all the time. You can be bummed or ecstatic or confused by just about every event of your life, just don't expect it to be glamorous.