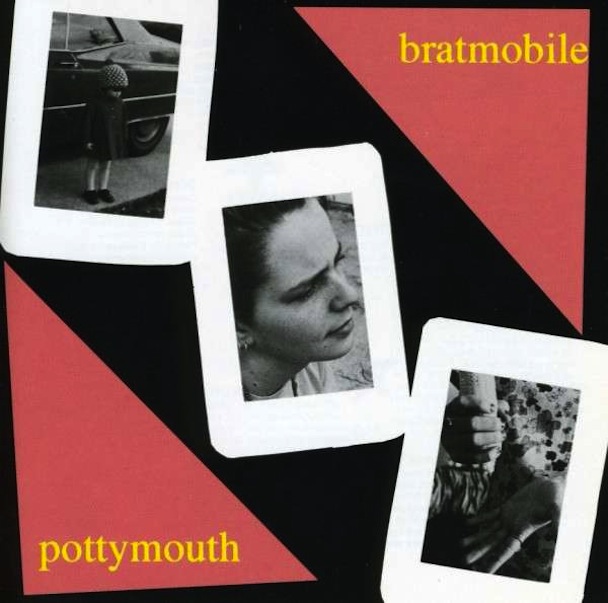

Has any band ever done unalloyed, sneering contempt quite as witheringly as Pottymouth-era Bratmobile? The only competitors I can think of are the Sex Pistols and the Circle Jerks, and I'm not entirely convinced that either one came close. Bratmobile reveled in the feeling. On "Love Thing," the first song from their first album, Allison Wolfe puts things as clearly as she possibly can: "I would die to not turn you on." One song later -- which is to say, 100 seconds later -- she's singing, "You'd like to stab me and fuck the wound" in a taunting playground singsong over a jittery lightspeed guitar jangle. Pottymouth blasts through its 17 songs in under 28 minutes, and its hooks jump and slash. Bratmobile's buddies Bikini Kill, inarguably the most important first-generation riot grrrl band, were about more than rage; they were also about community and friendship and sex and binary-breaking. Bratmobile, with their single-string surf-punk riffs and unflagging tempos, never had that sort of dimension to them. But they were the first riot grrrl band to release a great full-length album, and that makes them pretty goddam important too.

Listening back to Pottymouth today, two decades to the day after its release, it's striking how fun the album is, how viciously hooky and direct their songs are. Wolfe sings just slightly ahead of the beat most of the time, sometimes letting the muffled production swallow up her words, and guitarist Erin Smith plays those riffs as an all-at-once nervous lightspeed jangle. It's almost like they had to get all these songs out as quickly as possible, before they could convince themselves to hold back. Their songs are pointed and personal on at least some level; when Wolfe is screaming, "Get out of my fucking scene! / I hate your fucking scene!," it's easy to imagine that she has one particular individual person in mind as her target. But the album's no excorcism. It's got the total blast of discovery working in its favor. When you learn that the band's members learned their instruments just shortly before playing their first show, it's no surprise; that hey-we-can-do-this-too euphoria is all over this. And they also cranked out hooks like nobody's business; little touches like Wolfe's woo-woo disco call halfway through "Panik" are the sorts of things that stick with you when you hear them as a teenager. Musically, Pottymouth practically works as a basement version of the B-52s, the way most punk rock made by boys is a basement version of the Ramones or the Misfits or whatever.

Last year, when Bikini Kill's first EP turned 20, my wife asked me why I hadn't written one of these pieces about it, I told her that I was only writing these about albums. In retrospect, that was a pretty dumb decision on my part. Important musical moments can take all sorts of forms, and that first Bikini Kill EP was damn sure an important musical moment. Everything about that quick burst of riot grrrl was important, especially when you consider that punk shows, back then, were violent as hell and often actively dismissive of any sort of female presence. Figures like Sonic Youth's Kim Gordon and Black Flag's Kira Roessler were rare exceptions, and the idea of a group of women in the punk scene working in direct contradiction to the punk scene's prevailing attitudes -- well, it was pretty badass, and you probably don't need me to tell you that.

Over the years, the influence of that initial moment diffused a bit as it worked its way outward. A band like Sleater-Kinney, for instance, was able to build on that initial big bang, increasing its scope while keeping its ideals intact. The indie rock underground, as it exists, remains male as fuck, and there's lots of work to do. But we're looking at, for instance, a Pitchfork Music Festival where nearly half the acts are female or female-fronted, and I have to imagine that albums like Pottymouth had a ton to do with that. So the rudimentary urgency of Pottymouth was crucial in starting that wave up. It's a headlong attack of an album, short on insight but long on excitement, and that's what it needed to be. The bands that followed had the luxury of chilling out a bit. But I wish someone, of any gender, in any genre, was making music with the sort of urgency that Pottymouth brought.

In 1994, a year after Pottymouth dropped, Bratmobile broke up onstage, and the other bands of that initial riot grrrl wave didn't last much longer. But in 1999, Bratmobile got back together to tour with Sleater-Kinney, and they hang on long enough to release a couple more pretty good and surprisingly friendly albums. In 2002, the reunited Bratmobile played Baltimore, and I went to see them, mostly because Pottymouth had kicked my ass as a teenager. Double Dagger opened; it was their second show. I bought a pin. It was bright pink. You couldn't miss it. A month or two later, at a Britpop dance party at the same venue where I'd seen Bratmobile, I met the woman who would become my wife, and that Bratmobile pin made me about 500% cooler in her eyes. So, in some tiny way, I might owe Pottymouth my happiness. My kids might owe their lives to that album; there's a vague chance they they wouldn't exist without it. So it's a pretty important album from that standpoint, too.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]