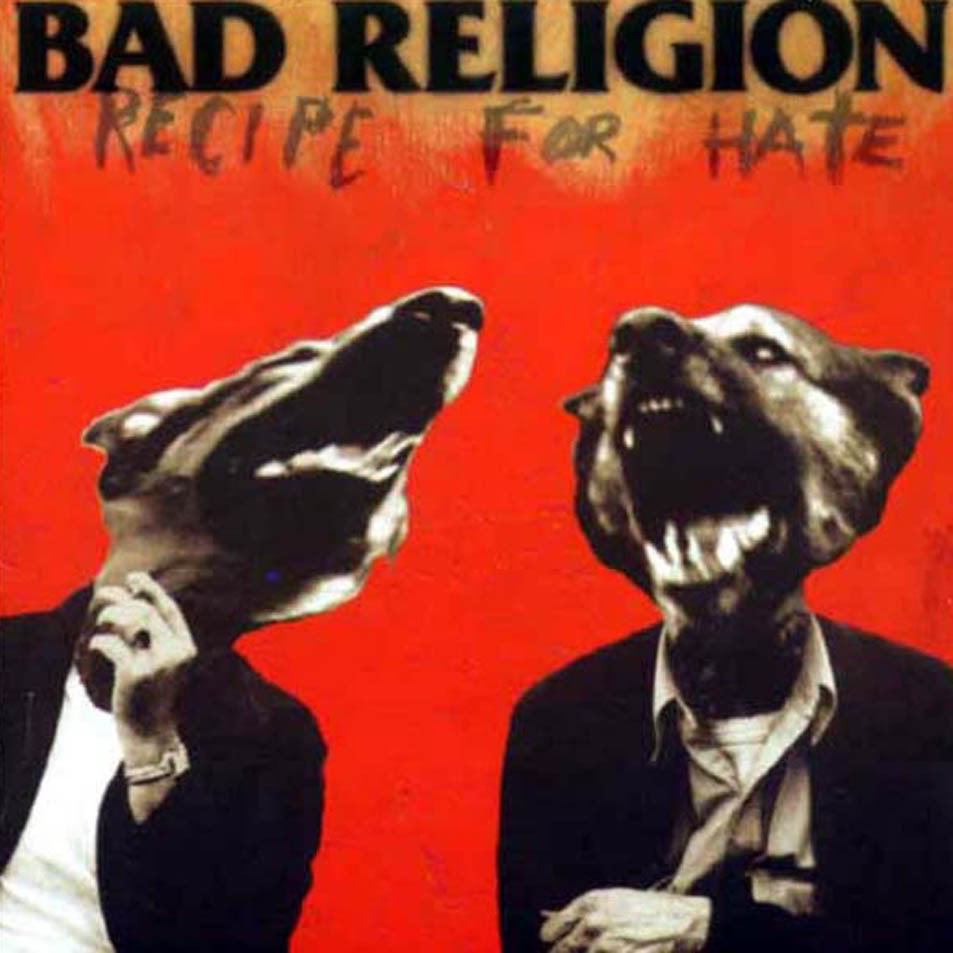

Bad Religion have existed for 33 years and released 16 albums, and the vast majority of those fit into one strict template: Rocketing muscular guitar grooves, hoarsely declarative Greg Graffin vocals, weirdly folky backing harmonies, syllable-crammed and vaguely political the-world-is-fucked lyrics, surging fists-up choruses. It's probably the most durable model in punk rock history, and it still sounded pretty great as recently as this year's True North. But within Bad Religion's vast discography, albums don't tend to stand out as big achievements. There are a couple of exceptions, though. Into The Unknown, the band's 1983 sophomore record, is an absolutely batshit-nuts piece of experimentation, one that finds the band pushing its feral early sound toward synth-prog grandiosity. It's a fascinating look at a road less taken, and the band almost immediately disowned it completely, breaking up for a couple of years after its release and then following it up with an EP called Back To The Known, thus pulling off one of the very few successful reboot moves in rock history. (Into The Unknown has been out of print since about 10 minutes after its release, but you can still find a shitty-quality rar if you put in enough Google work. You should. Shit is crazy.) And then there's 1993's Recipe For Hate. Musically, it's more or less an orthodox Bad Religion record with a few weird touches. But the circumstances around its release are, in retrospect, pretty fascinating: The band jumped to a major label for this one, and that major label did what it could to sell them as an alt-rock band, in the final moment that a wizened and respected California hardcore band wouldn't be an easy sell.

Recipe For Hate was the band's seventh album, and the previous six had all come out on Epitaph, the label that BR guitarist and co-leader Brett Gurewitz had founded (mostly just to put out Bad Religion albums). And they'd done just fine for themselves. The four albums after Into The Unknown, all great, had racked up crazy-impressive indie sales and built an honest-to-god cult around the band, to the point where half the young California punk bands in the early '90s sounded just like Bad Religion. (Gurewitz signed some of those soundalikes, like Pennywise and the Offspring, to Epitaph.) Bad Religion were also respected enough within their scene that, a few years before Recipe, Maxiumumrocknroll, the rigidly ascetic punk zine, released a goddam Bad Religion/Noam Chomsky split 7". But then the Nirvana wave happened, and every band who seemed remotely alternative found itself weighing competing major-label offers. First-wave hardcore bands like X and Circle Jerks and Flipper all ended up on big labels, presumably mostly because Kurt Cobain had said nice things about them in interviews. But they were all long past their peaks, and their post-grunge records were mostly pretty bad. (I will confess a soft spot for X's live acoustic record Unclogged.) But with Bad Religion, Atlantic somehow ended up with one of those early hardcore bands still operating at the peak of its powers -- one who had plenty to lose by aligning themselves with a bigger label. I don't know why Bad Religion left the house that they'd built for Atlantic, especially in an era when punks regularly excommunicated bands for reasons even dumber than that.

Musically, Recipe For Hate just sounds like a pretty good Bad Religion album, maybe one that's a step or two behind their previous few. A few of the songs -- "American Jesus," "Don't Pray On Me" -- absolutely whomp ass, hurtling along with the speed of righteous fury. And a few others make minor tweaks, letting in a big more guitar clangor than the generally tidy band had previously allowed. Eddie Vedder, of all people, sings backup on "Watch It Die," sounding pretty great, though I have to imagine this almost counted as a troll move in 1993. And Concrete Blond leader Johnette Napolitano absolutely crushes her spot on the single "Struck A Nerve." It's a big weird hearing a female voice on a Bad Religion song, especially one that can actually sing, but it works; "Struck A Nerve" probably stands as the album's best song. Still, by including those people, Bad Religion were probably inviting old fans to question their motives. And if they were trying to seem more like an alt-rock band, they were doing it wrong, since it turned out to be the exact wrong time for that.

About a year after Recipe For Hate, the Berkely popcore band Green Day blew the fuck up by releasing Dookie on a major label, and part of that album's appeal was that it seemed to have nothing to do with the post-Nirvana moment. Green Day were California punks who came off like California punks, while Bad Religion were California punks who came off like middle-aged guys with advanced degrees. (They were that, too.) And after Green Day, the Offspring, one of the Bad Religion disciples still on Epitaph, also had a titanic pop moment, and they had it without leaving Epitaph. Bad Religion could've stayed where they were, avoided alienating their base, and blown up anyway. Their whole situation reminds me of that scene from Office Space where the guy is stuck in traffic, and things always speed up in his lane as soon as he leaves it.

Things worked out fine for Bad Religion. A little more than a year later, the followed up Recipe with Stranger Than Fiction, which swapped out Vedder and Napolitano for guest vocals from Rancid's Tim Armstrong and Pennywise's Jim Lindberg, and the album ended up going gold. (Side note: I know this without looking it up because the great O.G. rock critic Robert Christgau, for the entire time I worked with him at the Village Voice, had a framed Stranger Than Fiction gold plaque up in his cubicle for some reason. It was the only decoration in there, and I thought about stealing it at least once a day.) A few albums later, they were back on Epitaph. They're still around. They won. But Recipe For Hate still marks a weird and fascinating moment, the rare occasion where they let a label attempt to sell them as something they weren't. Two decades later, there are still lessons to be learned from that album's story.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]