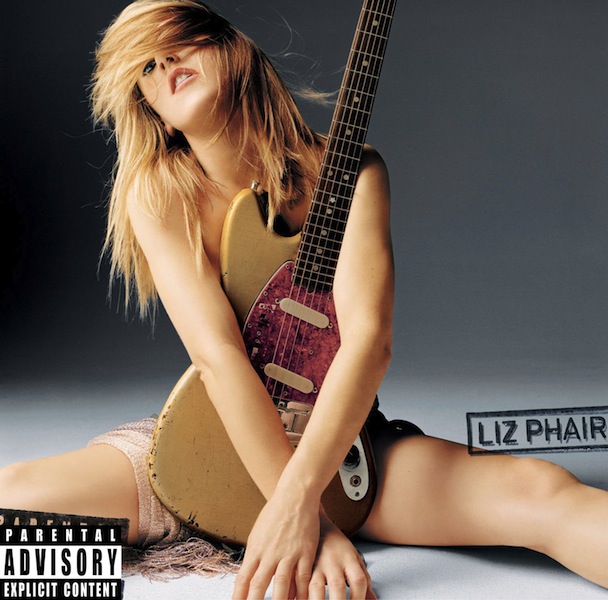

As chronicled by Tom last Friday, Exile In Guyville made Liz Phair an indie rock hero. The album blazed new trails: a woman invading (and mostly besting) a boys-club genre, addressing the thrills and spills of modern sexuality in bracingly honest fashion, delivered in the context of short stories deftly disguised as songs. She was a blowjob queen for the rest of us. Almost exactly 10 years later — and 10 years ago today — Phair released a record that undid most of that goodwill, turning her into a pariah among the audience that once heralded her as a genius. In its own way, though, that legendarily derided self-titled offering was as much of a trailblazer as Exile.

That's not to say it was anywhere near as good. Liz Phair was a weird record, and not weird in the art-damaged sense Phair's indie rock fan base might have hoped for; "awkward" is a better word for it. There were flashes of Phair's fearlessness and barbed wit, sometimes attached to melodies that ingratiated themselves immediately. But the good stuff mingled with garbage lyrics ("Oh, baby, know what you're like?/ You feel like my favorite underwear") and glossy boilerplate Top 40 production that couldn't have been farther from Exile's roughshod minimalism. The A.V. Club called it an identity crisis — "Even Phair doesn't seem to know who she is anymore" — but Phair repeatedly insisted it was exactly the record she wanted to make.

The album was cribbed from three separate recording sessions, which partly explains the lack of focus [1]. First, Phair and her touring band cut some tracks with Pete Yorn producer R. Walt Vincent, but not enough for an album. Next, at the suggestion of Capitol Records president Andy Slater, Phair wrote and recorded some songs with Michael Penn, but neither she nor the label was satisfied with the results. When Phair asked for funding for another round of recording, Slater agreed on the condition that she work with the Matrix, the production team behind hits by Avril Lavigne, Jason Mraz, and Hilary Duff. Those sessions yielded the most blatant radio bait of Phair's career, and neither she nor Capitol made any effort to hide the crossover motivations.

That went over with Phair's fan base about as well as Ted Danson in blackface at the Friars Club. To call Liz Phair a polarizing record among critics would wrongfully imply that there was a faction who vocally supported it. To be fair, the disc scored a handful of good grades: Entertainment Weekly declared it "an honestly fun summer disc," and Robert Christgau gave it an A in the Village Voice, explaining, "she further insults the indie world by successfully fusing the personal and the universal, challenging lowest-common-denominator values even as it fellates them." But even most of the positive reviews read more like faint praise. Rolling Stone shrugged, "Phair is a fine lyricist, and although she's lost some musical identity, she's gained potential Top Forty access." E!'s relatively friendly review said Phair "flirts with being Sheryl Crow-y bland now."

Most reviewers didn't fuck around with such passive aggression. The UK website No Ripcord called it "the ultimate middle finger." All Music Guide lamented, "she makes a long-delayed stab at superstardom, glamming herself up like a Maxim MILF of the Month and inexplicably pitching herself somewhere between Sheryl Crow and Avril Lavigne..." The Guardian complained, "Where she used to be smart and provocative, Phair has become crass and bloated, her lyrics crude and her image apparently a grotesque exercise in self-parody." Stylus gave it an F: "The tragedy is that Phair is wholly complicit in this utter waste of talent." Most famously, the record earned a 0.0 from Pitchfork, whose Matt LeMay fumed, "Ten years on from Exile, Liz has finally managed to achieve what seems to have been her goal ever since the possibility of commercial success first presented itself to her: to release an album that could have just as easily been made by anybody else." The only releases that scored worse on Metacritic that year were Puddle Of Mudd's Life On Display and Limp Bizkit's Results May Vary.

There was an overwhelming sense of betrayal in these reviews. This was personal. (Note LeMay's use of Phair's first name, as though they were pals.) Over the phone from L.A. last weekend, Phair remembered fielding interviews from furious scribes: "It was like therapy for these reviewers. They were angry at me. They were upset ... I really felt like I had to be this kind of therapist for these people, and let them vent their frustration at me." To critics who had embraced Phair as the leading lady of indie rock, releasing Michelle Branch soundalikes was a heel turn worthy of Dylan plugging in. She went from a messiah to a leper. "It was about me representing a movement for them or representing a type of person who was anti-establishment, who wouldn't be party to such mainstream-y music. They felt like I was a political candidate in a way."

Phair told me she didn't want to bear the burden of every album being an important artistic statement. From her perspective, she was just showing off a different side of the same person, a woman who could wear Chucks and jeans at the dive bar, then slip on a designer dress for her mother's garden party the next day (her example). "I just felt like, big picture, it's music," she said. "Really, if you don't like it, don't buy it, don't listen to it. But don't let it give you an ulcer, you know?"

Phair's analysis is astute. It would be dishonest to reduce the critique of that 2003 album to mere anti-pop bias, because some primary criticisms of the record run much deeper than that, and they ring true: Yeah, "H.W.C." is a dumbed-down version of Exile's sexcapades, and yeah, there's a lot of filler. There are legitimate reasons this record didn't make her a star. But many of the reviews read like Facebook screeds from spurned lovers — dispatches from the heart, not the brain. Critics felt like Phair was slumming. Why not leave this kind of thing to lesser talents? She had masterpieces to make. Mim Udovitch's insightful review at Slate summed up Liz Phair succinctly: It's "not so much a very bad record as it is a record about which it's easy to say very bad things."

Phair's pop pandering offended her old fans, but frankly, other than the aforementioned "Favorite" (as in "underwear"), the Matrix-produced songs are the best on the record. "Rock Me," in which Phair serenades a youthful lover with lines like "I want to play Xbox on your floor," doubles as a sequel to Exile's romantic foibles and a playful cougar prequel to Lana Del Rey's "Video Games" [2]. Opening number "Extraordinary" sounds like it emerged from a state-of-the-art songwriting machine, mostly in a good way. Lead single "Why Can't I," which could have easily been written for Avril, soars nonetheless and bears Phair's stamp in the form of the foul-mouthed outburst, "We haven't fucked yet but my head's still spinning" [3]. It's not epochal stuff, but I'm not turning it off if it comes on the radio either. There's no way the reaction would have been so visceral had anybody else been behind the mic.

That said, it's hard to imagine any indie musician taking so much flack today for going pop. Just a year after Liz Phair dropped, Kelly Clarkson's factory-built "Since U Been Gone" was accruing rave reviews and indie rock tributes [4]. Since then, critical thought and underground taste have transformed so much that, as Grantland's Steven Hyden pointed out, indie blogs were tripping over each other to post the new Mariah Carey song last month. The Village Voice critics poll, Pazz + Jop, still an accurate barometer of critical consensus, named "Call Me Maybe" the best single of 2012. Also in the Top 10: Country-pop superstar Taylor Swift, who would have the music press gargling "Why Can't I" like the mint Listerine it is if she released it as a single tomorrow. Pop stars including Katy Perry, Ke$ha, and even Justin Bieber merit serious critical adulation, whereas dismissing their kind used used to be a given. As Hyden tweeted, "Hipsters like Justin Timberlake and Beyonce in 2013, not the National. Please adjust your jokes accordingly."

It's not just fans and critics embracing pop, but artists too. If you're a hot new underground act, it's just as likely you make dance-pop as post-punk; the likes of Charli XCX, Jessie Ware, and Ellie Goulding get at least as much blog burn as Waxahatchee, White Lung, and Savages. Hip-hop and R&B have become the vanguard — Kanye West is our new Pink Floyd, you know. (Speaking of blurring the lines between mainstream and underground …) Furthermore, the concept of selling out no longer seems to raise hackles outside of certain DIY circles. Kurt Vile ruffled some feathers with pull quotes like, "I definitely think about success and I crave making more money," and, "In this day and age, 'punk ideals' are totally irrelevant," but there's an underlying understanding that the industry is crumbling and musicians gotta get paid somehow. Nobody is shitting on Icona Pop for making the leap to the Top 40. For indie audiences, making a break for the mainstream is no longer betrayal; it's aspirational.

None of this is news, and that's the point. In 2013, poptimism is the air we breathe. Why that happened is a complicated argument for another essay; just know that when the underground made its pilgrimage to pop, Liz Phair was already there waiting.

///

///

[1] In our interview, Phair cited splicing together material from different sessions with different producers as one of the ways this album was ahead of its time. That practice hasn’t really taken root in rock — bands still usually work with one producer, as opposed to pop, rap and dance projects that often mix and match producers — so it seems more like evidence of Phair leading an indie exodus toward pop than evidence of her changing the way rock records were made.

[2] Phair defended Lana Del Rey in a Wall Street Journal op-ed last year: "Let me break it down for you: she's writing herself into existence. She’s giving herself a part to play because, God knows, no one else will and she wants to matter in this life. As far as I can tell, it's working."

[3] LeMay's Pitchfork review suggests you could "change" ('fucked') to 'kissed' and stick a 16-year-old girl in front of the mic and no one could tell the difference,” but he's off base. That "fuck" means something. Replace "fuck" with "kiss" in "Fuck And Run," and you’d have a kiddie song too.

[4] Yes, Ted Leo was nodding at the shared riff between "Since U Been Gone" and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs' "Maps," but his cover seems to come from a place of admiration.