"My brother's back at home with his Beatles and his Stones/

But we never got it off on that revolution stuff/

What a drag/ Too many snags/

Now the television man is crazy saying we're juvenile delinquent wrecks/

Oh man, I need TV/ when I got T. Rex?"

-- David Bowie, "All The Young Dudes"

"I got your body right now on my mind/

but I drunk myself blind to the sound of old T. Rex"

-- The Who, "You Better You Bet"

In his famous 1953 essay of the same name, the German academic Isaiah Berlin elucidated a distinction between what he termed "the hedgehog and the fox." The essence of his hypothesis was that the two animals represented distinctly different kinds of thinkers: The fox knows many small things, but the hedgehog possesses one fundamental, overarching understanding. In terms of style quotient and sex appeal, T. Rex frontman Marc Bolan was certainly foxy -- a pixie-ish androgen capable of delivering nearly all of the UK into a multi-year pandemic known by the media's shorthand as "T. Rextasy." But in musical and songwriting terms, he was something like the ultimate hedgehog -- mining highly similar grooves and drum beats time and time again, recognizing their nearly primal capacity to move bodies and raise spirits. At the peak of his powers, on the classics Electric Warrior and The Slider, the songs could turn nearly indistinguishable at points. Amazingly the music became no less sublime for all the unselfconscious repetitiveness. Many great bands have possessed "signature sounds," but it requires a special temerity to essentially say: I am going to do the same thing over and over again every time and you are going to LOVE it every time. So what was the big thing Bolan knew?

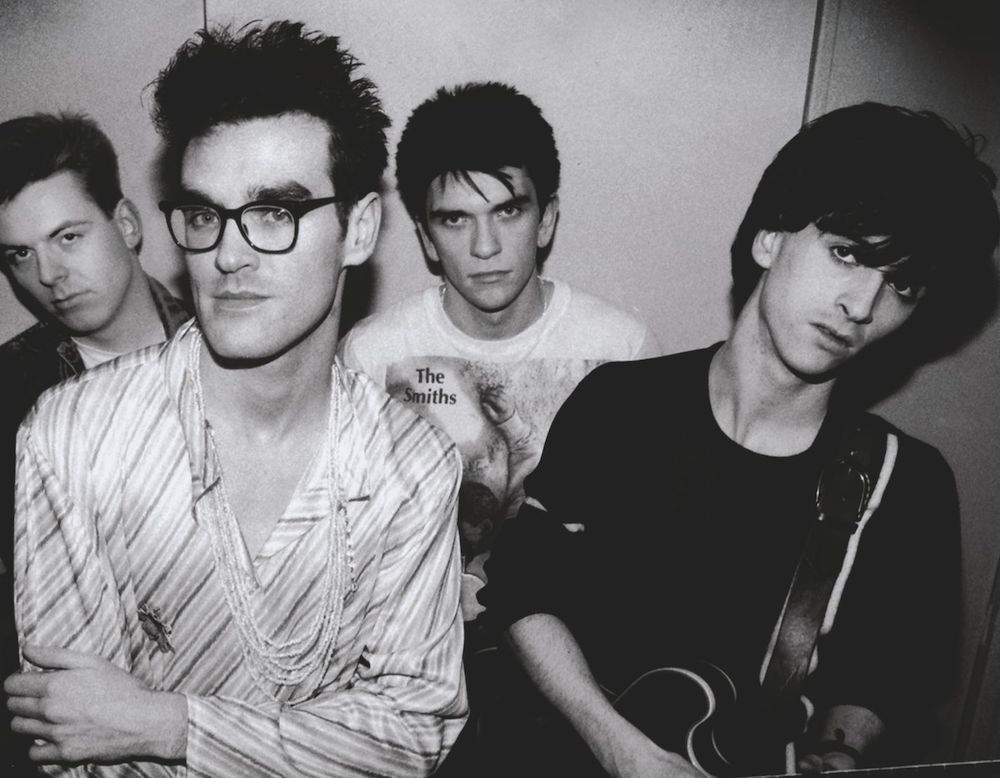

Few bands are as universally beloved as T. Rex, by fans and artistic peers alike, and part of Bolan's paradox is the deep meaning he embodied for hugely ambitious (and more than occasionally pretentious) artists like Townshend, Bowie, and Morrissey. While those performers have digressed and experimented at infinite length over marathon careers, Bolan represented an opposite approach. He was enormously nimble as a writer, player and a singer, but it cannot be asserted with absolute certainty that the man was actually terribly bright. His signature two-note guitar riff, as heard rumbling off the low E string on "Bang A Gong (Get In On)" is as individually characteristic and wonderful as Bo Diddley's shuffle or Chuck Berry's up-the-neck intros. It is also, perhaps not coincidentally, about the single most obvious thing to do for any person who happens to pick up a guitar. During the social and political hothouse of the early 1970's, Bolan remained steadfastly apolitical, or at least far from doctrinaire -- Vietnam and Altamont could scarcely turn his attention from the infinite carnal possibilities of well-rendered, bare-bones rock and roll. Somehow belying the R-rated nursery rhyme simplicity of their approach, his lyrics were curiously effective and affecting. It is difficult now to think of the artist who could delightfully deliver the lines "Woman/ I love your chest/ Baby, I'm crazy 'bout your breasts" without a single shred of shame or irony. This was a million miles from "Gimme Shelter."

But T. Rex's level of remove from proselytizing demagoguery was an understandable relief to rock music fans who had at this point been preached to at great length by the likes of Crosby, Stills & Nash. Acts like that had brought so much peace, love, and understanding to the popular consciousness that nothing less than a strict course of defiant hedonism could ever have corrected the balance. Bolan himself, always a latent hippie warrior, had begun his career with a series of forgettable "Summer Of Love"-era releases under the name Tyrannosaurus Rex. When he and Brooklyn-based producer Tony Visconti trashed that approach and functionally invented glam, it was the best thing to happen to rock and roll since the Elvis "Comeback Special" of 1968. What was revolutionary about T. Rex was its boundary pushing openness -- a fully recognized bending of gender concerns that considered the spectacle of fey, glitter-spackled waif-boys as fully normative two years in advance of Transformer and The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars.

His legacy lays not only in the spectacular nature of his unforgettable songs, but in the environment of early acceptance to a growing audience tired of being disenfranchised for not conforming to the macho/femme divide that had persisted through the early years of rock and roll and into the '70s. No wonder a captivated young Morrissey admittedly stole the riff and melody for the Smith's classic "Panic" from the great T. Rex track "Metal Guru." Bolan was never as erudite as his some of his followers, but he was never less honest, inspiring, and hugely entertaining.

Marc Bolan died in 1977, too young, the victim of a car accident. Although his demise at age 30 is awfully sad to consider, an honest critical assessment must ponder how much he really had left to offer creatively. By that time his vision of glam had been usurped in a number of ways -- on the industry end KISS had taken glitter and theatricality to new levels of cynical filthy lucre, while the far more underground New York Dolls had upped the ante on unalloyed rock sleaze. Bolan's late offerings never failed to provide flashes of his genius, but he was not the kind of artist to engage a sudden seismic shift in approach, and it feels likely that we were ultimately treated to the finest work he was capable of.

As for his legacy, Bolan's contribution feels as perversely polygamous as the sentiments expressed in his music. Other artists have been more influential, but have any been more imitated? It's impossible to imagine the Black Keys "Gold On The Ceiling" or Prince's "Cream" without Bolan. The Replacements, who covered T. Rex frequently, owe more to that band than any progenitor save the Faces. And the much maligned hair metal bands of the 1980s Sunset Strip, some of which will be redeemed by history, would never have been conceivable without their example.

Anyway, here are 10 of their best tunes. Check them out and raise a glass to old T. Rex.

10. "Ride a White Swan" (single, 1970)

In 1969, Marc Bolan parted ways with percussionist Steve Peregrin Took, hired drummer Mickey Finn, secured the services of Tony Visconti behind the board, and began the band's transformation from acoustic to electric. "Ride A White Swan" rose from the ashes of the extinct Tyrannosaurus Rex like a sparkly, glittering phoenix and flew in the face of listener expectations. As the first T. Rex hit single, it is replete with the big beats and memorable hooks that would define the newly minted band and introduce the world to glam. As a song, it's short, sweet, and indicative of the greatness to come.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

9. "Raw Ramp" (B-side to Get It On single, 1971)

Here, at the crossroads of Sleazeville and Raunch City, we have "Raw Ramp," perhaps the most unfettered instance of Bolan's id run wild, and a track which might make Dirty Mind-era Prince blush and retreat back to his Paisley Crib to think things over. Over a typically killer groove, Bolan begs and pleads to his chosen lady, whose lips, breasts, and "raw ramp" are objects of borderline obsession. He is literally on his knees. You have to accede to his overtures, lady, or Marc Bolan is probably going to spontaneously combust from sheer desire. As a bonus, the key-changing, tangentially related outro, touting the virtues of "electric boogie" is absolutely priceless. At this point in their trajectory, all cylinders were firing: Bolan and T. Rex could do no wrong.

8. "Telegram Sam" (from The Slider, 1972)

Yet another instant classic seemingly tossed off with shoulder shrugging ease during the Slider/Electric Warrior period, "Telegram Sam" evokes a more friendly version of the Velvets "Run, Run, Run" -- presenting a series of genially debased characters like "Jungle Faced Jake" and "Golden Nose Slim" who seem to mill about the ingratiating riff and melody, prepared to dispense pleasures at the ready. Most heroic of all is the titular hero -- possibly a drug dealer, maybe just a normal delivery guy -- but either way celebrated in one of the more soaring and inspired choruses in early '70s rock. He is, we're told, Bolan's "main man." And believe us -- that ain't nothing to sneeze at.

7. "Cosmic Dancer" (from Electric Warrior, 1971)

Here we have the essence of the soft soul behind all of the hedonism -- Bolan at his strangest and most melancholy. "Cosmic Dancer" is all wide eyed wonder and no small amount of existential terror, as the singer strikes a strangely confessional tone while explaining that he has ALWAYS been dancing, "danced himself right out of the womb," and in fact will ultimately dance until he dies. As acoustic guitar is gradually abetted by a lush orchestration, the song reaches a sort of panoramic transcendence, the more moving for being such an uncharacteristic moment amidst all the T. Rex revelry. What is keeping Bolan constantly boogie-ing, and why doesn't he seem able to stop? The song functions almost as a glam rock Grimm's Fairy Tale, sung by one who seems to recognize his light will burn brightly but briefly.

6. "Children Of The Revolution" (single, 1972)

One of the major preoccupations of glam, at least when it came to Marc Bolan and David Bowie, was with "the children": the young dudes, the children that you spit on, the children of the revolution. In an era when songs about revolution of one kind or another were nearly ubiquitous, it should come as no surprise that T. Rex would have their own unique take on the idiom. For Bolan, revolution was something less political and more social and sexual, and "Children Of The Revolution" seems to want to give an anthem to any bi-curious person who wanted to walk around in drag or glitter or heels. Their particular revolution wasn't against an oppressive class system or an outrage over Vietnam, but instead created an ersatz army of social outcasts who didn't fit into the cookie cutter roles of gender or behaving as typically macho or feminine. And there are legions of these children and in some sense the revolution they were leading was equally -- if not more -- important to dismantling the status quo. This was the sort of revolution that was adopted by everyone from Elton John to Lady Gaga.

5. "Bang A Gong (Get It On)" (from Electric Warrior, 1971)

Nothing about "Get It On" should work -- from the multiple saxophones, to piano virtuoso Rick Wakeman's talents used only to play the occasional glissando, to Bolan's preposterous lyrics (nobody, not a sex therapist, not a best friend, should ever offer the two pieces of advice "Get it on, bang a gong" in the same breath -- who owns a gong, anyway?!), and yet the insane combination of these elements gets the job done and then some. With a killer riff and infectious groove, "Bang A Gong (Get It On)" takes us from the ridiculous to the sublime. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this was the only track to make serious inroads into the recklessly depraved American market of the early '70s.

4. "20th Century Boy" (single, 1973)

By the time of this epochal 1973 single, the T. Rex creative juggernaut had begun to show signs of slowing up a bit. But beginning with a spate of feedback and a furious two note opening riff, "20th Century Boy" is one last hit of pure crystalline magic. Bolan is clearly not fucking around here -- the track is unusually crowded and aggressive, pushing glam towards its harder edges and logical extremes. While the lyrical content is a fairly standard advertisement for the availability of Bolan's affections, the metallic edge and amphetamine drive lend the entire track a profound sense of decadence and desperation -- the nature boy let loose in the city on the last night of an epic bender.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

3. "Baby Strange" (from The Slider, 1972)

Certain apocryphal (if plausible) stories tell of Bolan bragging about his ability to write hit songs in the elevator on the way to the studio. With its simple but insinuating two chord riff, pounding back beat and rakishly charming lyrics (what sane woman would not be romanced by the earnestly crooned couplet "I wanna call ya/I wanna ball ya"?) one can imagine "Baby Strange" being just this kind of song. That it actually resolves into a fantastically cool and relatively sophisticated chorus with a couple of Chilton-esque turns and flourishes only serves to remind that T. Rex can throw a melodic curveball with the best of them. They just usually don't feel like it.

2. "Jeepster" (from Electric Warrior, 1971)

The joyous bounce of this insistent, infectious gem is the sort of perfectly manicured pop bauble that only Bolan and the band could carry off and make it appear this easy. The regular presence of congas in the band's lineup frequently lends a winsome, nearly comedic air to T. Rex tracks, but there is no doubt the extra percussion also provides unusual texture to their precision groove, and never more so than here. Meanwhile, Bolan's waxes typically gnomic and horny: "Girl I'm just a vampire for your love/ And I'm gonna suck you!" Is there no end to this man's reservoir of amazing pick-up lines??

1. "Metal Guru" (from The Slider, 1972)

From the Beatles with the Maharishi to Pete Townshend with Maher Baba, British rock stars of the early '70s were drawn in waves to the sketchier sides of Eastern philosophy. It's unclear who T. Rex's metal guru is -- Bolan's preoccupations seemed more along the lines of paganism and magickal thinking -- but the song is in ways apiece with other tributes to spiritual avatars like "Baba O'Riley" or "My Sweet Lord" and is as buoyant and life-affirming as either of these tracks. It underscores the notion that Bolan, at base, was a deeply spiritual cat, profoundly enraptured by music and a lust for life. The resonance of his output has proved timeless -- he is indeed a cosmic dancer.