As I began the writing, listening, and reading for this list, I started to think about a weird quality of Bruce Springsteen's catalogue that I hadn't previously considered. For someone I've grown up knowing as an already well-established icon, it's surprising to look at his body of work and realize the bizarre patterns within: it's all kind of fits and starts, multiple "make or break" moments, long stretches of inactivity blowing open with sudden and sustained productivity. You don't really consider this when you're just presented with a list of his classic albums and how they ranked on all these "Best Albums of" whatever lists in whichever magazine in whichever year, but Springsteen did a lot of things that you'd assume should've sunk his career.

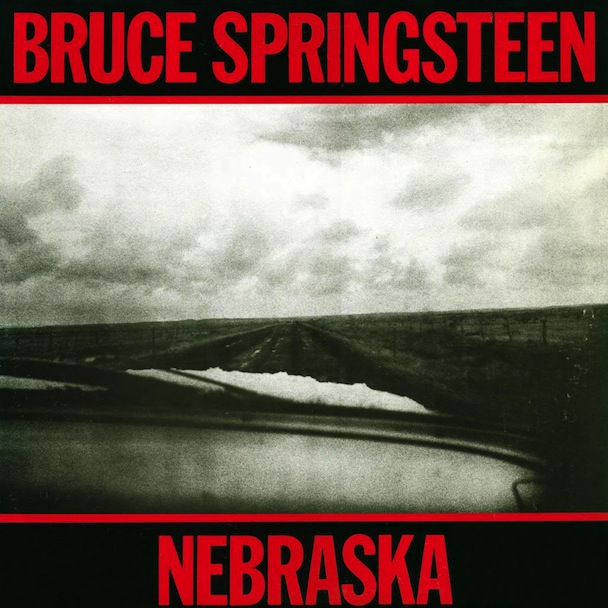

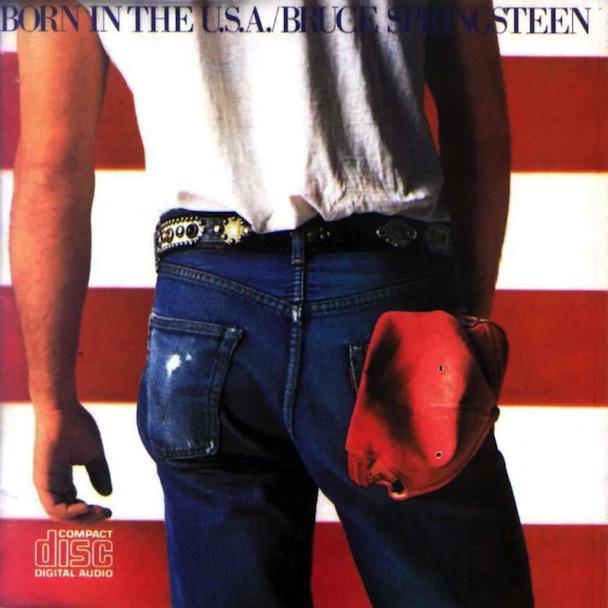

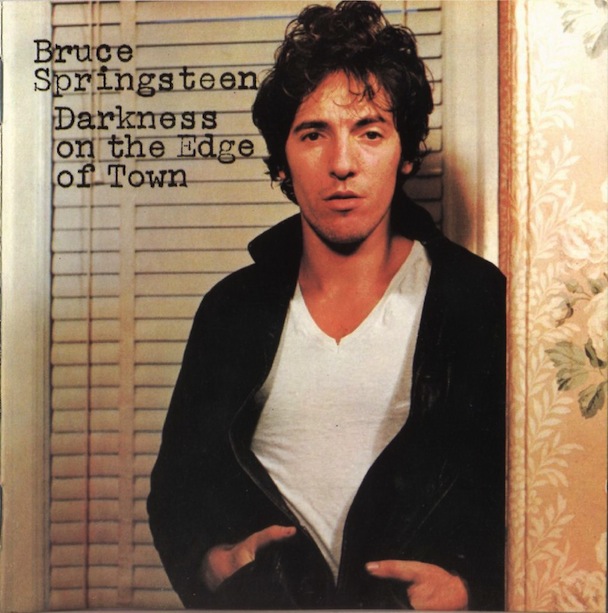

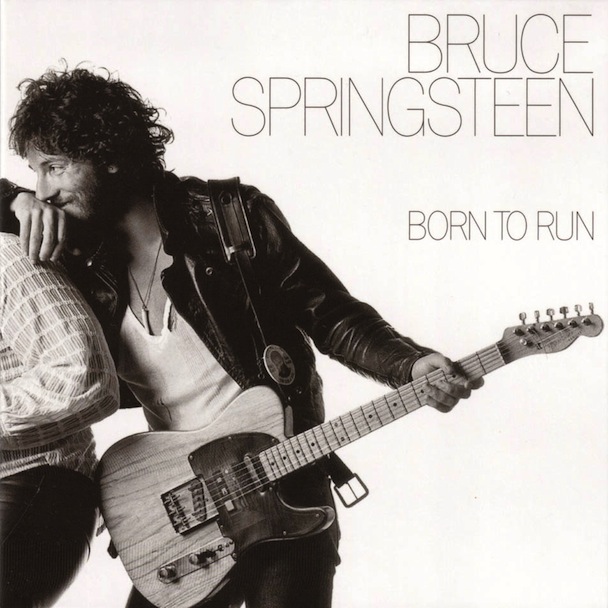

After finally breaking through with Born To Run in 1975, circumstances prevented him from releasing another album until 1978, and he chose to go harder and more bitter, and gave everyone Darkness On The Edge Of Town. In 1980 he released a double album, The River, that rather than being bloated and overblown was a collection of sharply written and fervently performed pop songs that heightened his mainstream profile. Surely, then, he would keep that momentum, release another rock album? Not exactly — he put out the dark, primarily acoustic Nebraska instead in 1982. The same went down with Born In The U.S.A. in 1984 and the mellower, more personal Tunnel Of Love in 1987. And so on. When you're dealing with a retrospective like this for an artist like Bruce Springsteen, it's hard to find your entry point, to figure out who you're writing for. It's harder still when confronted with a recording career spanning four decades that has more twists and turns than are readily apparent.

There have been two narratives in Springsteen's career that have long interested me. The first is the perpetual pull between romanticism and realism within his career, his shifts between mythologizing and reporting. People have written about this, but I think the borders are more permeable on many of his albums than you'd initially suspect. Where relevant, I try to trace his oscillations between the two modes, in the process trying to figure out what each moment means not only to his career but also to a larger cultural narrative.

The second is the uniqueness of Springsteen's artistic trajectory. He was a young, rising rock star, with a hot streak that ran from his early twenties to his late thirties. And then, he stopped putting albums out frequently, largely sat out the '90s, and effectively skipped the middle-aged soul-searching and listlessness of an aging pop star. When Springsteen was fully back on the radar, he was in his fifties and already an elder statesman, a cultural icon, but one who was also (frequently) making new music that people still deemed important. He's also taken on a kind of second life as a luminary for particular wings of the contemporary indie rock world. There doesn't seem to be anyone else who has had a career quite like that, though there are a few parallels with Neil Young and Bob Dylan. Particularly for the entries on Springsteen's '00s work, I've tried to dig into what it means that this has been the shape his career has taken.

With Springsteen's tour in support of last year's Wrecking Ball soon drawing to a close, thus ending this chapter of his career, it seems as good a time as any to dig into the rich history of the man's music. This week also brought the release of the documentary Springsteen & I, making Bruce an even timelier subject. This is a list for Springsteen's studio recordings. That means all the E Street Band and solo records, the Seeger Sessions album, as well as the collections The Promise and Tracks. I've left off live material for multiple reasons, one of which is that a lot of diehard fans will cite certain bootlegs as being superior to any official live release, and that's just a whole messy world for another list to address. The other is that most fans will tell you that you need to see Springsteen live to fully experience his music, and they're right -- it'll change your life. I'll mention how certain songs are translated live, but I'm most concerned with how he's structured his albums and what their stories are, so that's what I'll be focusing on here. For people unfamiliar with Springsteen, I've tried to give an overview of his career through the stories of the albums — an admittedly incomplete introduction, but maybe one that will help you find your way into Springsteen's music. For longtime fans, hopefully I'll be able to present you with some new ideas. If there's a contrarian out there who wants to argue the merits of Human Touch, take it to the comments.

19. Human Touch (1992)

By the end of the 1980s, feeling penned in by his success and the need to explore other creative frontiers, Springsteen dismissed the E Street Band. The process had already started, with him having recorded much of 1987's Tunnel Of Love by himself and various members of the E Street Band contributing to varying degrees after the fact, some quite minimally — or, in the case of saxophonist Clarence Clemons, not at all. Nevertheless, Springsteen wound up working with pianist/keyboardist Roy Bittan (who had joined the E Street Band before Born To Run), excited by Bittan's new synthesizers and a few instrumental tracks he'd written on them. What resulted was the lengthy, reportedly arduous, but enjoyable process of recording Human Touch, the first album Springsteen cut with session musicians.

Released in 1992, Human Touch is easily Springsteen's weakest album. From a production standpoint, most of the material here is sickeningly slick, all terrible synth and guitar tones that, just over 20 years on, sound more like the low-budget soundtrack to a forgotten early-'90s TV show than something put out by one of the most important pop stars in America. On the songwriting front, things aren't much better. Call it an alarming and sudden drying up of the well, or maybe a residual creative confusion of not having his longtime band with him, but Springsteen spends most of Human Touch sounding like what lesser songwriters sound like when they try to be him. The main exception would be the title track, which, despite bearing some similarities to the superior "Tunnel Of Love," is a pretty strong song for the era, and performed well as a single.

Though it received a more mixed reception than past Springsteen efforts — which were almost always received rapturously — Human Touch wasn't universally reviled upon its release. But it has aged badly, and seeing Springsteen tour in support of it with a faceless group of hired hands didn't sit well with fans or longtime members of Springsteen's crew. In the wake of the inevitable but still triumphant reunion with the E Street Band in 1999, most fans seem content to half-forget this album ever happened and resign its memory to the lost years of Springsteen's '90s.

19. Human Touch (1992)

By the end of the 1980s, feeling penned in by his success and the need to explore other creative frontiers, Springsteen dismissed the E Street Band. The process had already started, with him having recorded much of 1987's Tunnel Of Love by himself and various members of the E Street Band contributing to varying degrees after the fact, some quite minimally — or, in the case of saxophonist Clarence Clemons, not at all. Nevertheless, Springsteen wound up working with pianist/keyboardist Roy Bittan (who had joined the E Street Band before Born To Run), excited by Bittan's new synthesizers and a few instrumental tracks he'd written on them. What resulted was the lengthy, reportedly arduous, but enjoyable process of recording Human Touch, the first album Springsteen cut with session musicians.

Released in 1992, Human Touch is easily Springsteen's weakest album. From a production standpoint, most of the material here is sickeningly slick, all terrible synth and guitar tones that, just over 20 years on, sound more like the low-budget soundtrack to a forgotten early-'90s TV show than something put out by one of the most important pop stars in America. On the songwriting front, things aren't much better. Call it an alarming and sudden drying up of the well, or maybe a residual creative confusion of not having his longtime band with him, but Springsteen spends most of Human Touch sounding like what lesser songwriters sound like when they try to be him. The main exception would be the title track, which, despite bearing some similarities to the superior "Tunnel Of Love," is a pretty strong song for the era, and performed well as a single.

Though it received a more mixed reception than past Springsteen efforts — which were almost always received rapturously — Human Touch wasn't universally reviled upon its release. But it has aged badly, and seeing Springsteen tour in support of it with a faceless group of hired hands didn't sit well with fans or longtime members of Springsteen's crew. In the wake of the inevitable but still triumphant reunion with the E Street Band in 1999, most fans seem content to half-forget this album ever happened and resign its memory to the lost years of Springsteen's '90s.

18. Lucky Town (1992)

After all the time and effort poured into Human Touch, Springsteen was apparently struck with a sudden lightness and inspiration that allowed him to cut a whole 'nother record in just weeks. Following the template just set by Guns 'N Roses releasing Use Your Illusions I and II on the same day, Springsteen and manager Jon Landau made their case for doing the same with Human Touch and Lucky Town. It was released on March 31, 1992, along with Human Touch, as they'd wished.

Originally, I was going to just list Human Touch and Lucky Town together, arguing they collectively represented the same low point in Springsteen's career. No doubt, there are plenty of the same issues here — the studio musicians, songs that feel like hollow Springsteen imitations — but Lucky Town is also clearly better than Human Touch by a decent margin. It's still not great, and is still easily at the bottom end of his catalogue, but it's better than I had given it credit for, perhaps due to the fact that it's inextricably linked to Human Touch through their shared release date.

Much of Lucky Town actually feels like Springsteen, which is a marked difference from the generic gloss of Human Touch. Comparatively, it's rougher, but that doesn't make it some raucous echo of The River or something; assisted by the clinical hand of a studio band rather than the E Street Band, there's still a certain soul lacking here. Thankfully, the songwriting talents that were lacking on Human Touch crop up more here. "If I Should Fall Behind" was actually played with the reunited E Street Band, unlike almost anything else from this era, and "Living Proof" seems to have its supporters amongst certain wings of the fan base. Personally, I've always thought "Better Days" and "Lucky Town" were pretty strong.

After the dual release of Human Touch and Lucky Town met with a relatively more muted response commercially and critically, Springsteen spent a lot of the '90s laying low, by his standards. He began raising a family, spent time living in L.A. and traveling through the Southwest. On the heels of the massive success of the 1994 single "Streets Of Philadelphia," he recorded a whole album of like-minded songs, only to never release it, instead putting out the sparse The Ghost Of Tom Joad in 1995. As the decade tipped toward its second half, the idea of reuniting with the E Street Band was already flickering in his mind enough to warrant a one-off, and reportedly awkward, occasion to record a few new songs for his 1995 Greatest Hits. By the end of the '90s the full-fledged reunion would be realized, Springsteen's least productive or engaging decade would be behind him, and Lucky Town would mainly be left in the past with it.

18. Lucky Town (1992)

After all the time and effort poured into Human Touch, Springsteen was apparently struck with a sudden lightness and inspiration that allowed him to cut a whole 'nother record in just weeks. Following the template just set by Guns 'N Roses releasing Use Your Illusions I and II on the same day, Springsteen and manager Jon Landau made their case for doing the same with Human Touch and Lucky Town. It was released on March 31, 1992, along with Human Touch, as they'd wished.

Originally, I was going to just list Human Touch and Lucky Town together, arguing they collectively represented the same low point in Springsteen's career. No doubt, there are plenty of the same issues here — the studio musicians, songs that feel like hollow Springsteen imitations — but Lucky Town is also clearly better than Human Touch by a decent margin. It's still not great, and is still easily at the bottom end of his catalogue, but it's better than I had given it credit for, perhaps due to the fact that it's inextricably linked to Human Touch through their shared release date.

Much of Lucky Town actually feels like Springsteen, which is a marked difference from the generic gloss of Human Touch. Comparatively, it's rougher, but that doesn't make it some raucous echo of The River or something; assisted by the clinical hand of a studio band rather than the E Street Band, there's still a certain soul lacking here. Thankfully, the songwriting talents that were lacking on Human Touch crop up more here. "If I Should Fall Behind" was actually played with the reunited E Street Band, unlike almost anything else from this era, and "Living Proof" seems to have its supporters amongst certain wings of the fan base. Personally, I've always thought "Better Days" and "Lucky Town" were pretty strong.

After the dual release of Human Touch and Lucky Town met with a relatively more muted response commercially and critically, Springsteen spent a lot of the '90s laying low, by his standards. He began raising a family, spent time living in L.A. and traveling through the Southwest. On the heels of the massive success of the 1994 single "Streets Of Philadelphia," he recorded a whole album of like-minded songs, only to never release it, instead putting out the sparse The Ghost Of Tom Joad in 1995. As the decade tipped toward its second half, the idea of reuniting with the E Street Band was already flickering in his mind enough to warrant a one-off, and reportedly awkward, occasion to record a few new songs for his 1995 Greatest Hits. By the end of the '90s the full-fledged reunion would be realized, Springsteen's least productive or engaging decade would be behind him, and Lucky Town would mainly be left in the past with it.

17. Working On A Dream (2009)

After his quietest decade, Springsteen roared back with one of the most productive streaks of his career, releasing six albums in 10 years. It started in 2002 with The Rising, then tumbled through 2005's Devils & Dust, 2006's We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions, 2007's Magic, 2009's Working On A Dream, and finally 2012's Wrecking Ball. This isn't taking into account the perpetual touring in-between these releases, or the reissue of Darkness On The Edge Of Town in late 2010, which came with The Promise, a two-disc archival project of shelved recordings from the late '70s. Somewhere in the midst of this, one would have to imagine there would be a project that felt less thought-through, a bit weaker. That project would be Working On A Dream.

Each of Springsteen's latter day releases of original material has felt like a pointed response to current events in some form or another. In hindsight, Working On A Dream sounds like a knee-jerk, perhaps naïve moment of getting caught up in the wave of optimism just after Obama's election. Throughout, Springsteen deploys a lot of his stock tricks, but also explores lighter, poppier structures that he often resisted in the earlier years of his career. Things are glistening and near-unwaveringly romantic on Working On A Dream in a way that feels foreign to Springsteen's work. This isn't necessarily to begrudge the man a moment of lightness. At this juncture in his career, and in the midst of such a productive streak, and sandwiched between a lot of albums that addressed heavy subject matter ranging from 9/11 to the war in Iraq, Springsteen had certainly earned the right to kick back and experiment a bit. The disappointing thing is that the resulting album just sort of feels like a hodgepodge, populated by songs that feel like brighter B-sides to Magic, released just 16 months prior.

There are some strong moments here. "My Lucky Day" is pretty by-the-numbers latter day Springsteen pop, but has one of the catchier and more enduring melodies from the album. There's "The Last Carnival," a moving tribute to recently deceased organist Danny Federici, a member since the original lineup of the E Street Band. And tacked on the end, as a bonus track, there's "The Wrestler," a poignant song Springsteen wrote for the Mickey Rourke movie of the same name. Elsewhere, though, Springsteen descends into the saccharine ("This Life," "Surprise, Surprise") and self-parody ("Outlaw Pete," "Queen Of The Supermarket"), two things he's usually done well at avoiding. Not all the songs I just mentioned are bad, but a lot of the stuff on Working On A Dream is lesser Springsteen material, and in the midst of a renewed strong streak, it becomes a more or less forgettable album.

17. Working On A Dream (2009)

After his quietest decade, Springsteen roared back with one of the most productive streaks of his career, releasing six albums in 10 years. It started in 2002 with The Rising, then tumbled through 2005's Devils & Dust, 2006's We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions, 2007's Magic, 2009's Working On A Dream, and finally 2012's Wrecking Ball. This isn't taking into account the perpetual touring in-between these releases, or the reissue of Darkness On The Edge Of Town in late 2010, which came with The Promise, a two-disc archival project of shelved recordings from the late '70s. Somewhere in the midst of this, one would have to imagine there would be a project that felt less thought-through, a bit weaker. That project would be Working On A Dream.

Each of Springsteen's latter day releases of original material has felt like a pointed response to current events in some form or another. In hindsight, Working On A Dream sounds like a knee-jerk, perhaps naïve moment of getting caught up in the wave of optimism just after Obama's election. Throughout, Springsteen deploys a lot of his stock tricks, but also explores lighter, poppier structures that he often resisted in the earlier years of his career. Things are glistening and near-unwaveringly romantic on Working On A Dream in a way that feels foreign to Springsteen's work. This isn't necessarily to begrudge the man a moment of lightness. At this juncture in his career, and in the midst of such a productive streak, and sandwiched between a lot of albums that addressed heavy subject matter ranging from 9/11 to the war in Iraq, Springsteen had certainly earned the right to kick back and experiment a bit. The disappointing thing is that the resulting album just sort of feels like a hodgepodge, populated by songs that feel like brighter B-sides to Magic, released just 16 months prior.

There are some strong moments here. "My Lucky Day" is pretty by-the-numbers latter day Springsteen pop, but has one of the catchier and more enduring melodies from the album. There's "The Last Carnival," a moving tribute to recently deceased organist Danny Federici, a member since the original lineup of the E Street Band. And tacked on the end, as a bonus track, there's "The Wrestler," a poignant song Springsteen wrote for the Mickey Rourke movie of the same name. Elsewhere, though, Springsteen descends into the saccharine ("This Life," "Surprise, Surprise") and self-parody ("Outlaw Pete," "Queen Of The Supermarket"), two things he's usually done well at avoiding. Not all the songs I just mentioned are bad, but a lot of the stuff on Working On A Dream is lesser Springsteen material, and in the midst of a renewed strong streak, it becomes a more or less forgettable album.

16. We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions (2006)

We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions is an oddity in Springsteen's catalogue. It's a covers album, first off, and rather than something a longtime fan might expect from that description (like, say, a collection of the classic '50s and '60s rock and roll songs Springsteen often plays on tour), it's a tribute to American folk singer Pete Seeger. Recorded off-the-cuff at his farm in 2006, the project actually has roots in 1997, when Springsteen contributed a cover of "We Shall Overcome" for another Seeger tribute. Returning to the idea nearly a decade later, it's easy to regard The Seeger Sessions as an odd artistic indulgence that wouldn't really resonate with fans — hell, Springsteen himself wasn't even that familiar with Seeger at the time of his initial cover, let alone his fanbase. And yet, it was quite successful given its nature. It won the Grammy for Best Traditional Folk Album in 2007, and garnered a near-unanimous stream of positive reviews from critics (oddly, some of the most uniform praise of his '00s output). It's sold enough to be certified gold — which, you'd have to imagine, is a feat for any traditional folk album in the 21st century, even with Springsteen's name attached.

The praise wasn't necessarily undeserved. The Seeger Sessions is loose and fun where much of Springsteen's '00s output had been (and continued to be) meticulously considered and produced. The degree to which you enjoy it is beholden to your degree of interest in old-timey folk music, though, which is a blight that doesn't seem to apply to any other example of Springsteen's work. Even previous stylistic detours like Devils & Dust and Nebraska feel very much a part of the man's overall career narrative, the latter of course being essential, and definitively still Springsteen in a way that just isn't occurring here. So, despite the project's warm reception and general success, The Seeger Sessions is ranked so low because it can't help but feel like one of the most minor entries into the Springsteen canon. After all, there's something telling about the fact that the accompanying 56-date tour was under-attended in America — in an era where Springsteen is still a touring behemoth when on the road with the E Street Band — and the fact that the whole era was reduced to two and a half pages in Peter Ames Carlin's 2012 biography Bruce.

I also can't say I've witnessed any fan become overly excited when Bruce occasionally trots out one of the old Seeger Sessions covers on subsequent tours with the E Street Band. That's something best left to Live In Dublin, the live album that commemorated the Seeger Sessions tour. Most interestingly, Live In Dublin also featured multiple arrangements of his originals, made to fit with the DNA of the Seeger Sessions album and band. Some of these are excellent, invigorating old classics or more recent standard rock songs in unexpected ways. Despite the project's roots in American folk music, there's something distinctly Old World about some of these arrangements, namely "Further On (Up The Road)" and the incredible re-envisioning of "Atlantic City." This is perhaps the most engaging lingering notion about the Seeger Sessions detour: the idea that within Springsteen there could be the capacity for a new path late in his career. That he could age out, eventually, into a mystic on the borders (not unlike how Dylan has reinvented himself as an ancient, apocalyptically voiced bluesman), and become a purveyor of ramshackle gypsy folk. For now, Springsteen can still bring the bombast though, which keeps We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions from transcending its status as a career footnote.

16. We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions (2006)

We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions is an oddity in Springsteen's catalogue. It's a covers album, first off, and rather than something a longtime fan might expect from that description (like, say, a collection of the classic '50s and '60s rock and roll songs Springsteen often plays on tour), it's a tribute to American folk singer Pete Seeger. Recorded off-the-cuff at his farm in 2006, the project actually has roots in 1997, when Springsteen contributed a cover of "We Shall Overcome" for another Seeger tribute. Returning to the idea nearly a decade later, it's easy to regard The Seeger Sessions as an odd artistic indulgence that wouldn't really resonate with fans — hell, Springsteen himself wasn't even that familiar with Seeger at the time of his initial cover, let alone his fanbase. And yet, it was quite successful given its nature. It won the Grammy for Best Traditional Folk Album in 2007, and garnered a near-unanimous stream of positive reviews from critics (oddly, some of the most uniform praise of his '00s output). It's sold enough to be certified gold — which, you'd have to imagine, is a feat for any traditional folk album in the 21st century, even with Springsteen's name attached.

The praise wasn't necessarily undeserved. The Seeger Sessions is loose and fun where much of Springsteen's '00s output had been (and continued to be) meticulously considered and produced. The degree to which you enjoy it is beholden to your degree of interest in old-timey folk music, though, which is a blight that doesn't seem to apply to any other example of Springsteen's work. Even previous stylistic detours like Devils & Dust and Nebraska feel very much a part of the man's overall career narrative, the latter of course being essential, and definitively still Springsteen in a way that just isn't occurring here. So, despite the project's warm reception and general success, The Seeger Sessions is ranked so low because it can't help but feel like one of the most minor entries into the Springsteen canon. After all, there's something telling about the fact that the accompanying 56-date tour was under-attended in America — in an era where Springsteen is still a touring behemoth when on the road with the E Street Band — and the fact that the whole era was reduced to two and a half pages in Peter Ames Carlin's 2012 biography Bruce.

I also can't say I've witnessed any fan become overly excited when Bruce occasionally trots out one of the old Seeger Sessions covers on subsequent tours with the E Street Band. That's something best left to Live In Dublin, the live album that commemorated the Seeger Sessions tour. Most interestingly, Live In Dublin also featured multiple arrangements of his originals, made to fit with the DNA of the Seeger Sessions album and band. Some of these are excellent, invigorating old classics or more recent standard rock songs in unexpected ways. Despite the project's roots in American folk music, there's something distinctly Old World about some of these arrangements, namely "Further On (Up The Road)" and the incredible re-envisioning of "Atlantic City." This is perhaps the most engaging lingering notion about the Seeger Sessions detour: the idea that within Springsteen there could be the capacity for a new path late in his career. That he could age out, eventually, into a mystic on the borders (not unlike how Dylan has reinvented himself as an ancient, apocalyptically voiced bluesman), and become a purveyor of ramshackle gypsy folk. For now, Springsteen can still bring the bombast though, which keeps We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions from transcending its status as a career footnote.

15. The Ghost Of Tom Joad (1995)

After seeing John Ford's 1940 adaptation of The Grapes Of Wrath on TV in the late '70s, Springsteen would go on to mine the film for inspiration for years, especially as his work would turn towards grittier, more realist depictions of working class struggles. With 1995's The Ghost Of Tom Joad, however, he made it overt, adopting the protagonist of John Steinbeck's novel as a sort of folk icon for social causes and blue-collar woes. A collection of stripped-back, meditative acoustic songs dealing with often dreary accounts of the working life, the album's obvious antecedent is 1982's Nebraska, which was the first time Springsteen had simultaneously turned to darker and folkier methods to tell these sorts of stories.

Unlike Nebraska, however, The Ghost Of Tom Joad can drift by without leaving a mark, which is obviously a major failure for an album so fixated on bringing attention to social ills. Something notable relative to the rest of Springsteen's work is the geographic recalibration. Written during Springsteen's time living in L.A., The Ghost Of Tom Joad is directly inspired by not only his regular motorcycle trips through the deserts of the American Southwest, but also by how he found himself relating with Southern California's communities of Mexican immigrants. Many of the stories and characters here may feel of a piece with his larger concerns — and they are — but they also highlight a specific element of America's class narrative that Springsteen hadn't delved into in quite the same way before. Unfortunately, he doesn't mine that new influence to bring new elements into the music.

In many cases the stories are all that will linger from these songs. Every song is built on gentle and serviceable finger-picked guitar, with the occasional embellishment: a harmonica, a violin, a synth drone in the backdrop. Occasionally, this works beautifully, as in the title track and "Youngstown," both haunting enough to rank with some of the material from Nebraska. This could be traced to the fact that not only do these songs boast the most fleshed-out instrumentation, they also feature memorable vocal melodies. Too often on this album, the story is told in Springsteen's subtle, reedy whispers, and it all begins to feel a bit repetitive and indiscernible. In terms of Springsteen's '90s work, this is certainly more dialed in than Human Touch or Lucky Town, but it's still underwhelming musically.

This isn't a knock against Springsteen doing minimalism; we know from Nebraska that he can excel at that. The thing about Nebraska is that you can't shake it because it's all raw demos that emphasize the desperation and isolation of the stories therein. The Ghost Of Tom Joad is, by contrast, very clearly produced, it's just underdone from a writing standpoint. Many of these songs demand a righteous fury, something all the more obvious after taking in a live E Street Band performance of "The Ghost Of Tom Joad." That's especially true for the times where Rage Against The Machine's Tom Morello has joined them, like on their tour of Australia in March. Likewise, the brooding full-band treatment of "Youngstown" is stunning, particularly when Bruce recites the closing lines: "When I die I don't want no part of heaven/ I would not do heaven's work well/ I pray the devil comes and takes me/ To stand in the fiery furnaces of hell." He extends "hell" into a wail, Nils Lofgren unleashes a searing solo, and you feel the ferocity of the narrator.

There were actually sessions where they attempted to record a full-band version of Nebraska, which have never been released. I'd love to hear those, but I don't suspect for a moment that they'd surpass the album that was released in 1982. But with The Ghost Of Tom Joad, these full-band renditions are striking, suggesting other forms these songs could have taken, a way in which they could have been as gripping and unsettling as Springsteen surely intended them to be.

15. The Ghost Of Tom Joad (1995)

After seeing John Ford's 1940 adaptation of The Grapes Of Wrath on TV in the late '70s, Springsteen would go on to mine the film for inspiration for years, especially as his work would turn towards grittier, more realist depictions of working class struggles. With 1995's The Ghost Of Tom Joad, however, he made it overt, adopting the protagonist of John Steinbeck's novel as a sort of folk icon for social causes and blue-collar woes. A collection of stripped-back, meditative acoustic songs dealing with often dreary accounts of the working life, the album's obvious antecedent is 1982's Nebraska, which was the first time Springsteen had simultaneously turned to darker and folkier methods to tell these sorts of stories.

Unlike Nebraska, however, The Ghost Of Tom Joad can drift by without leaving a mark, which is obviously a major failure for an album so fixated on bringing attention to social ills. Something notable relative to the rest of Springsteen's work is the geographic recalibration. Written during Springsteen's time living in L.A., The Ghost Of Tom Joad is directly inspired by not only his regular motorcycle trips through the deserts of the American Southwest, but also by how he found himself relating with Southern California's communities of Mexican immigrants. Many of the stories and characters here may feel of a piece with his larger concerns — and they are — but they also highlight a specific element of America's class narrative that Springsteen hadn't delved into in quite the same way before. Unfortunately, he doesn't mine that new influence to bring new elements into the music.

In many cases the stories are all that will linger from these songs. Every song is built on gentle and serviceable finger-picked guitar, with the occasional embellishment: a harmonica, a violin, a synth drone in the backdrop. Occasionally, this works beautifully, as in the title track and "Youngstown," both haunting enough to rank with some of the material from Nebraska. This could be traced to the fact that not only do these songs boast the most fleshed-out instrumentation, they also feature memorable vocal melodies. Too often on this album, the story is told in Springsteen's subtle, reedy whispers, and it all begins to feel a bit repetitive and indiscernible. In terms of Springsteen's '90s work, this is certainly more dialed in than Human Touch or Lucky Town, but it's still underwhelming musically.

This isn't a knock against Springsteen doing minimalism; we know from Nebraska that he can excel at that. The thing about Nebraska is that you can't shake it because it's all raw demos that emphasize the desperation and isolation of the stories therein. The Ghost Of Tom Joad is, by contrast, very clearly produced, it's just underdone from a writing standpoint. Many of these songs demand a righteous fury, something all the more obvious after taking in a live E Street Band performance of "The Ghost Of Tom Joad." That's especially true for the times where Rage Against The Machine's Tom Morello has joined them, like on their tour of Australia in March. Likewise, the brooding full-band treatment of "Youngstown" is stunning, particularly when Bruce recites the closing lines: "When I die I don't want no part of heaven/ I would not do heaven's work well/ I pray the devil comes and takes me/ To stand in the fiery furnaces of hell." He extends "hell" into a wail, Nils Lofgren unleashes a searing solo, and you feel the ferocity of the narrator.

There were actually sessions where they attempted to record a full-band version of Nebraska, which have never been released. I'd love to hear those, but I don't suspect for a moment that they'd surpass the album that was released in 1982. But with The Ghost Of Tom Joad, these full-band renditions are striking, suggesting other forms these songs could have taken, a way in which they could have been as gripping and unsettling as Springsteen surely intended them to be.

14. Magic (2007)

I hadn't gone back to Magic for a while until I started working on this list, but now that I have, I've realized two things. First, I like it more than I remembered. The second thing is that more and more I'm coming to view The Rising, Devils & Dust, Magic, and Wrecking Ball as one continuing project, which is making it difficult to rank one against the other.

As I touched on in the intro, since Bruce returned with the E Street Band at the turn of this century, he's become very much an oddity in the pop landscape. He was no longer just another recording artist; he was an operating legend. His classic era is spoken of with awe. The thing is, it wasn't like he was still operational in the same way as older artists like Paul McCartney or the Stones, people who could still make a killing touring but rarely, if ever, made a record that mattered anymore. Instead, each new Bruce album still managed to evoke fervent reactions, deeply considered essays. He managed to do something that you'd assume would be impossible: emerging out of a (relative) 10-year exile as he exits middle age, getting the old band back together, and taking it well beyond the victory-lap celebration of the past and into a period of frenzied productivity in which he was still a relevant recording artist. Some fans may quibble with the new stuff, and of course there are always going to be those who will just straight-up dislike anything post '84 or '87. Conversely, there will always be those who overpraise the new stuff just because it's Springsteen. I'm going to try to walk a path between the two: I've already made my case for Working On A Dream and The Seeger Sessions being minor works, but I think some of these other '00s records are really, really good, and perhaps underrated in the grand scheme of Springsteen's career.

Perhaps more importantly, outside of all this music world business, Springsteen came back and was a cultural icon. People now expected him to issue his statement on Our Country Today, and all that. And, well, he came back in a decade ripe with opportunities for commentary. Magic was, up until that point, the most pointedly political of the latter day Springsteen works. "Gypsy Biker," "Livin' In the Future," "Last To Die," "Long Walk Home," and the title track all addressed the political atmosphere of the mid-aughts in some fashion or another. Collapsed into a few tracks were loads of critique, primarily of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, but also of our government's behavior post-9/11. In a larger sense, there seems to be a dread and a detachment hanging over the whole affair. Whether the searching-through-the-desolation of "Radio Nowhere" or the complicated hometown relationship sketched out in "Long Walk Home," Springsteen seemed to be trying to make sense of a country that no longer seemed familiar to him. For an artist known for social commentary, and now almost mandated to have his finger on the pulse of the country, that disassociation and confusion would be the most telling, and invigorating, strands in Magic.

There's something else we need to talk about with '00s Bruce, and that's the issue of production. Having brought on producer Brendan O'Brien with The Rising, a lot of Springsteen's recent albums have taken on a modern rock gloss (that goes for even the ones done without O'Brien) that doesn't seem fitting to Springsteen's music in general, nor the ideas he's trying to convey. Everything about Magic feels too compressed and synthetically punchy, slick to the point where it feels overcooked and distant at times. The sepia-toned cover art, though appealing aesthetically, seems symbolic: It has a sort of proto-Instagram relationship to authenticity, relying on digital alterations both visual and sonic to achieve the sense of grunginess that the E Street Band could more than easily bring to driving rock music like this on their own. That all holds Magic back from engaging in the same way as some of Bruce's best work. It's all rugged sheen, but underneath we're denied the true grit we need to connect with the issues at hand.

14. Magic (2007)

I hadn't gone back to Magic for a while until I started working on this list, but now that I have, I've realized two things. First, I like it more than I remembered. The second thing is that more and more I'm coming to view The Rising, Devils & Dust, Magic, and Wrecking Ball as one continuing project, which is making it difficult to rank one against the other.

As I touched on in the intro, since Bruce returned with the E Street Band at the turn of this century, he's become very much an oddity in the pop landscape. He was no longer just another recording artist; he was an operating legend. His classic era is spoken of with awe. The thing is, it wasn't like he was still operational in the same way as older artists like Paul McCartney or the Stones, people who could still make a killing touring but rarely, if ever, made a record that mattered anymore. Instead, each new Bruce album still managed to evoke fervent reactions, deeply considered essays. He managed to do something that you'd assume would be impossible: emerging out of a (relative) 10-year exile as he exits middle age, getting the old band back together, and taking it well beyond the victory-lap celebration of the past and into a period of frenzied productivity in which he was still a relevant recording artist. Some fans may quibble with the new stuff, and of course there are always going to be those who will just straight-up dislike anything post '84 or '87. Conversely, there will always be those who overpraise the new stuff just because it's Springsteen. I'm going to try to walk a path between the two: I've already made my case for Working On A Dream and The Seeger Sessions being minor works, but I think some of these other '00s records are really, really good, and perhaps underrated in the grand scheme of Springsteen's career.

Perhaps more importantly, outside of all this music world business, Springsteen came back and was a cultural icon. People now expected him to issue his statement on Our Country Today, and all that. And, well, he came back in a decade ripe with opportunities for commentary. Magic was, up until that point, the most pointedly political of the latter day Springsteen works. "Gypsy Biker," "Livin' In the Future," "Last To Die," "Long Walk Home," and the title track all addressed the political atmosphere of the mid-aughts in some fashion or another. Collapsed into a few tracks were loads of critique, primarily of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, but also of our government's behavior post-9/11. In a larger sense, there seems to be a dread and a detachment hanging over the whole affair. Whether the searching-through-the-desolation of "Radio Nowhere" or the complicated hometown relationship sketched out in "Long Walk Home," Springsteen seemed to be trying to make sense of a country that no longer seemed familiar to him. For an artist known for social commentary, and now almost mandated to have his finger on the pulse of the country, that disassociation and confusion would be the most telling, and invigorating, strands in Magic.

There's something else we need to talk about with '00s Bruce, and that's the issue of production. Having brought on producer Brendan O'Brien with The Rising, a lot of Springsteen's recent albums have taken on a modern rock gloss (that goes for even the ones done without O'Brien) that doesn't seem fitting to Springsteen's music in general, nor the ideas he's trying to convey. Everything about Magic feels too compressed and synthetically punchy, slick to the point where it feels overcooked and distant at times. The sepia-toned cover art, though appealing aesthetically, seems symbolic: It has a sort of proto-Instagram relationship to authenticity, relying on digital alterations both visual and sonic to achieve the sense of grunginess that the E Street Band could more than easily bring to driving rock music like this on their own. That all holds Magic back from engaging in the same way as some of Bruce's best work. It's all rugged sheen, but underneath we're denied the true grit we need to connect with the issues at hand.

13. Wrecking Ball (2012)

Last year, a few months after its release, I wrote at length about Wrecking Ball. While I don't have the space here to rehash that whole argument, I'm going to touch on it again, because a year removed I stand by it, and I think it makes Wrecking Ball possibly the most interesting latter day Springsteen record.

I have a sense that this is an unpopular opinion. Nevertheless, I've never really understood fans who complained about this album. It has a few duds, sure. "Jack Of All Trades" isn't quite "Queen Of The Supermarket" self-parody territory, but is certainly lazy Springsteen-by-numbers. As much as Springsteen put it forth as a mission statement for the album and accompanying tour, I could never really get into "Rocky Ground," probably because of that rap verse, which just sort of felt ridiculous. "You've Got It" is a decent track, but feels off topic, and I still can't decide if the music behind "We Are Alive" is fitting or a bit goofy. Other than that, my main gripe is that "Land Of Hope And Dreams" finally made it on an album and I don't like this version as much as the one they first premiered during the Reunion tour.

Other than a few qualms though, I feel like Wrecking Ball is the most vital Springsteen has sounded in almost the entirety of his '00s streak. "We Take Care Of Our Own" uses a few classic Springsteen tricks, like the glockenspiel accenting a main string melody, but manages to make it feel fresh, perhaps because the song is built on a pulse that's insistent and infectious. (Somehow, bizarrely, there were those who followed in the footsteps of George Will, who infamously called "Born In The U.S.A." a "grand, cheerful affirmation," and mistook the sardonic nature of the chorus as blind jingoism.) I find myself more eager to turn up the stomp of "Easy Money," "Shackled And Drawn," or "Death To My Hometown" than most of Magic. Wrecking Ball still suffers from Springsteen's perennial over-production ills in his latter day work and like with Magic, a rawer sound would probably have evoked the drive of the lyrics better (as would having recorded it with the full E Street Band, rather than partially solo and partially with their contributions). But the best moments here have a muscle and pulse that effectively pull out the defiance of the protest song tradition Springsteen was trying to quote. And in a live setting, he brings a roar to these songs usually reserved for the old classics.

When Wrecking Ball came out last year, a lot of people criticized its protest elements. Some dismissed it because it marked Bruce covering familiar territory, which is partially understandable but also partially bizarre — hasn't he spent most of his career detailing the plight of the working man? And it would seem, post-Recession, that he'd be needed more than ever. This is that sense that there's a mandate for Springsteen to react to each social and political moment now, that of course we would get Springsteen's Recession record, just as we had received his 9/11 and Iraq and Obama records. Perhaps, then, I can relate more to some of the other criticisms: that while this is familiar territory for Springsteen, and while it was a somewhat expected record, the real problem is that the critiques feel more black and white than in the past, less nuanced.

Paradoxically, it's the confusion and failings of Wrecking Ball that make me find it so fascinating or, as I argued in my essay last year, strangely and perhaps accidentally successful. Essentially, yes, a lot of the protest lyrics are more stereotypical than what we've become accustomed to with Springsteen, but that's just part of the messy mashup of romanticism and realism that occurs on Wrecking Ball. After the fantastical left turn of Working On A Dream, Wrecking Ball feels more fully engaged with our contemporary reality precisely because of the way in which it breaks down the supposed barrier between realism and romanticism in Springsteen's career. The music's a bit mythic, the lyrics archetypal but more grounded, and it all comes together in a way that confusingly vacillates between fantasy and reality in a way that feels true to being alive (or perhaps, at least, young) in 2013. More so than Magic or Working On A Dream, when Wrecking Ball came out I felt as if I'd experienced the release of a Springsteen album that felt specifically, pivotally, about the times I was living in, its flaws and failings making it only more so.

13. Wrecking Ball (2012)

Last year, a few months after its release, I wrote at length about Wrecking Ball. While I don't have the space here to rehash that whole argument, I'm going to touch on it again, because a year removed I stand by it, and I think it makes Wrecking Ball possibly the most interesting latter day Springsteen record.

I have a sense that this is an unpopular opinion. Nevertheless, I've never really understood fans who complained about this album. It has a few duds, sure. "Jack Of All Trades" isn't quite "Queen Of The Supermarket" self-parody territory, but is certainly lazy Springsteen-by-numbers. As much as Springsteen put it forth as a mission statement for the album and accompanying tour, I could never really get into "Rocky Ground," probably because of that rap verse, which just sort of felt ridiculous. "You've Got It" is a decent track, but feels off topic, and I still can't decide if the music behind "We Are Alive" is fitting or a bit goofy. Other than that, my main gripe is that "Land Of Hope And Dreams" finally made it on an album and I don't like this version as much as the one they first premiered during the Reunion tour.

Other than a few qualms though, I feel like Wrecking Ball is the most vital Springsteen has sounded in almost the entirety of his '00s streak. "We Take Care Of Our Own" uses a few classic Springsteen tricks, like the glockenspiel accenting a main string melody, but manages to make it feel fresh, perhaps because the song is built on a pulse that's insistent and infectious. (Somehow, bizarrely, there were those who followed in the footsteps of George Will, who infamously called "Born In The U.S.A." a "grand, cheerful affirmation," and mistook the sardonic nature of the chorus as blind jingoism.) I find myself more eager to turn up the stomp of "Easy Money," "Shackled And Drawn," or "Death To My Hometown" than most of Magic. Wrecking Ball still suffers from Springsteen's perennial over-production ills in his latter day work and like with Magic, a rawer sound would probably have evoked the drive of the lyrics better (as would having recorded it with the full E Street Band, rather than partially solo and partially with their contributions). But the best moments here have a muscle and pulse that effectively pull out the defiance of the protest song tradition Springsteen was trying to quote. And in a live setting, he brings a roar to these songs usually reserved for the old classics.

When Wrecking Ball came out last year, a lot of people criticized its protest elements. Some dismissed it because it marked Bruce covering familiar territory, which is partially understandable but also partially bizarre — hasn't he spent most of his career detailing the plight of the working man? And it would seem, post-Recession, that he'd be needed more than ever. This is that sense that there's a mandate for Springsteen to react to each social and political moment now, that of course we would get Springsteen's Recession record, just as we had received his 9/11 and Iraq and Obama records. Perhaps, then, I can relate more to some of the other criticisms: that while this is familiar territory for Springsteen, and while it was a somewhat expected record, the real problem is that the critiques feel more black and white than in the past, less nuanced.

Paradoxically, it's the confusion and failings of Wrecking Ball that make me find it so fascinating or, as I argued in my essay last year, strangely and perhaps accidentally successful. Essentially, yes, a lot of the protest lyrics are more stereotypical than what we've become accustomed to with Springsteen, but that's just part of the messy mashup of romanticism and realism that occurs on Wrecking Ball. After the fantastical left turn of Working On A Dream, Wrecking Ball feels more fully engaged with our contemporary reality precisely because of the way in which it breaks down the supposed barrier between realism and romanticism in Springsteen's career. The music's a bit mythic, the lyrics archetypal but more grounded, and it all comes together in a way that confusingly vacillates between fantasy and reality in a way that feels true to being alive (or perhaps, at least, young) in 2013. More so than Magic or Working On A Dream, when Wrecking Ball came out I felt as if I'd experienced the release of a Springsteen album that felt specifically, pivotally, about the times I was living in, its flaws and failings making it only more so.

12. Devils & Dust (2005)

I seem to have memories of Devils & Dust coming out in 2004, and people talking a lot about Springsteen's politics. In hindsight, I'm convinced this must have had more to do with the controversy over "American Skin (41 Shots)" from a few years before, and from Springsteen's participation in the 2004 Vote For Change tour. Though the title track was written in 2003 and is evidently in reaction to the war in Iraq, much of the album dates back to the time of The Ghost Of Tom Joad ("All The Way Home," a standout here, actually goes back to the early '90s). Fittingly, a lot of Devils & Dust seems to draw more direct inspiration from Springsteen's '90s Southwest wanderings than it does from his frustration with our country's actions 10 years ago.

Brendan O'Brien was brought on board again, and in this instance seems to have helped correct everything that was wrong with The Ghost Of Tom Joad. There are still a few less-defined tracks, but where much of The Ghost Of Tom Joad was nondescript musically, Devils & Dust is mostly fleshed out and the right amount of lush — simultaneously full but organic enough to suggest the power of the desert landscape. Select members of the E Street Band add touches here and there, mostly offering Western stylings that made the music and stories within resonate in a way they didn't on The Ghost Of Tom Joad.

While only the title track is discernibly political, the national conflicts of the day hang over Devils & Dust like a shroud, inevitably casting it as a tale of two deserts. Springsteen might be revisiting old material, but the timing can't be an accident. As he watched our nation stumble awkwardly through one faraway desert, Springsteen returned to America's own wasteland, perhaps as an older traveler looking for (and failing to find) the potential of the frontier that he had sought desperately in his youth. Perhaps it's just a larger idea of wanderers lost in alien landscapes, a man finding no fulfillment with an encounter with a prostitute in "Reno" not all that different from the men at war in "Devils & Dust." There's a subtle interplay between the suggestion of distance between these scenes and their similarities. "We're a long, long way from home, Bobbie/ Home's a long, long way from us," the narrator of "Devils & Dust" says, and he could be talking about being adrift in either desert. In a line, Springsteen seems to sum up the detachment that would result from a decade of a nation's lurching missteps.

For some reason, Devils & Dust has been largely ignored since Springsteen's solo tour in 2005. A few of the songs have been played here and there, but none with any real frequency, which is bizarre considering the power the E Street Band could bring to "All The Way Home" or "Maria's Bed" — the latter a very overlooked song, one of his best latter day tracks. There's precedent, anyway, with Nebraska and The Ghost Of Tom Joad songs getting fairly regular rotation. Whatever the reason, Devils & Dust has always seemed unfairly sidelined. It's easily the strongest material we've yet to hear that has any roots in his '90s writing, and is also one of the more satisfying records to come out during his '00s streak. There isn't much in Springsteen's lauded catalogue that you could call "underrated," but if anything would qualify, it would be Devils & Dust.

12. Devils & Dust (2005)

I seem to have memories of Devils & Dust coming out in 2004, and people talking a lot about Springsteen's politics. In hindsight, I'm convinced this must have had more to do with the controversy over "American Skin (41 Shots)" from a few years before, and from Springsteen's participation in the 2004 Vote For Change tour. Though the title track was written in 2003 and is evidently in reaction to the war in Iraq, much of the album dates back to the time of The Ghost Of Tom Joad ("All The Way Home," a standout here, actually goes back to the early '90s). Fittingly, a lot of Devils & Dust seems to draw more direct inspiration from Springsteen's '90s Southwest wanderings than it does from his frustration with our country's actions 10 years ago.

Brendan O'Brien was brought on board again, and in this instance seems to have helped correct everything that was wrong with The Ghost Of Tom Joad. There are still a few less-defined tracks, but where much of The Ghost Of Tom Joad was nondescript musically, Devils & Dust is mostly fleshed out and the right amount of lush — simultaneously full but organic enough to suggest the power of the desert landscape. Select members of the E Street Band add touches here and there, mostly offering Western stylings that made the music and stories within resonate in a way they didn't on The Ghost Of Tom Joad.

While only the title track is discernibly political, the national conflicts of the day hang over Devils & Dust like a shroud, inevitably casting it as a tale of two deserts. Springsteen might be revisiting old material, but the timing can't be an accident. As he watched our nation stumble awkwardly through one faraway desert, Springsteen returned to America's own wasteland, perhaps as an older traveler looking for (and failing to find) the potential of the frontier that he had sought desperately in his youth. Perhaps it's just a larger idea of wanderers lost in alien landscapes, a man finding no fulfillment with an encounter with a prostitute in "Reno" not all that different from the men at war in "Devils & Dust." There's a subtle interplay between the suggestion of distance between these scenes and their similarities. "We're a long, long way from home, Bobbie/ Home's a long, long way from us," the narrator of "Devils & Dust" says, and he could be talking about being adrift in either desert. In a line, Springsteen seems to sum up the detachment that would result from a decade of a nation's lurching missteps.

For some reason, Devils & Dust has been largely ignored since Springsteen's solo tour in 2005. A few of the songs have been played here and there, but none with any real frequency, which is bizarre considering the power the E Street Band could bring to "All The Way Home" or "Maria's Bed" — the latter a very overlooked song, one of his best latter day tracks. There's precedent, anyway, with Nebraska and The Ghost Of Tom Joad songs getting fairly regular rotation. Whatever the reason, Devils & Dust has always seemed unfairly sidelined. It's easily the strongest material we've yet to hear that has any roots in his '90s writing, and is also one of the more satisfying records to come out during his '00s streak. There isn't much in Springsteen's lauded catalogue that you could call "underrated," but if anything would qualify, it would be Devils & Dust.

11. The Rising (2002)

The Rising is an album loaded with symbolism for its place in Springsteen's career alone, not to mention its moment in a larger cultural context. Not an album of firsts, necessarily, but an album of "firsts in a while." Springsteen's first record of new material in seven years, his first rock album in 10 years, since Lucky Town in 1992. His first record since reuniting the E Street Band, which makes it the first record with the entire E Street Band since Born In The U.S.A. in 1984. Within his story alone, it's full of new beginnings.

The story goes that at some point within the first few days after 9/11, Springsteen sat at the water in Jersey and looked across to see the smoking wreckage at the southern tip of Manhattan. A man passed him, rolled down his car window, and called out, "We need you, man!" In that single anecdote, you get the whole idea that when Bruce & the E Street Band returned, it wasn't in the typical way of just another functioning artist. He was a beacon, a force that people hung upon to provide insight and guidance in one of our country's most traumatic moments (and what would go on to continue to be a traumatic decade).

It wasn't going to be a 9/11 record originally, and some of the songs date back before 2001. "My City Of Ruins," for example, was originally written about the dilapidation of Asbury Park, only to be re-contextualized to be about New York, and about America as a whole. But much of the record was written in the wake of the attacks, and whether you trace it back to the man calling from his car or to Springsteen having the strange experience of seeing multiple obituaries that noted how victims were huge fans of his, there's no real way The Rising wasn't going to be about 9/11. And in terms of his artistic development, this is integral. For better or for worse, Springsteen has now spent 10 years mainly being a chronicler in a way that's more specific to contemporary moments than his past work, but there's no question that taking on that mantle has provided the rush of inspiration that turned away from the mainly uninspired (and uninspiring) '90s and towards his prolific '00s. That starts with The Rising.

Despite it garnering critical acclaim and commercial success upon its release, I feel like whenever I hear people mention The Rising now it's not always in the most complimentary way. It might be a bit overlong, but its epic quality feels fitting for the moment at hand, both a fervent marker of Springsteen's return and an unrestrained attempt to capture the national climate. On that latter note, one of the perennial criticisms could be understood: The Rising does often traffic in vague universalities, especially when compared to the work of Springsteen's heyday. That sort of feels important and specific to the purposes of The Rising, though. Sure, there are a few songs that felt a little adult-contemporary or stock modern rock, and I can't really argue with that, though I don't dislike any of the material here. Maybe some fans are just fatigued — out of any of Springsteen's '00s releases, The Rising doesn't seem to have ever fell out of the live rotation, with its title track and "Waitin' On A Sunny Day" almost as likely to be played at any given show as "Born To Run" or "Dancing In The Dark."

Still, I can't help but be impressed with The Rising. Springsteen emerged out of the '90s with his band after an almost two-decade absence, and he emerged with a fully formed new sense of purpose and sound. In comparison to the '00s albums that followed, this feels like the E Street Band is involved, even though they're playing in an entirely different way than they used to.

And it's a crucial entry in Springsteen's catalogue for the radically different tone it has in comparison to most of his work. The Rising is outside of that realism/romanticism binary. It deals with a sober reality, and has sober realities within its songs, but its uplifting moments are not the moments of romantic escape from his past work, nor the blind optimism of Working On A Dream. Rather, they're hope at a time when our country needed it and when he as an artist had earned the right to seek it. In a way, that might suggest The Rising is rooted in its time. But that's where a vague universality, in a very rare instance, works. We'll always have the bleakness of Nebraska and, later, the anger of Magic and Wrecking Ball to remind us of the realities and troubles Springsteen is reacting to. The Rising doesn't shy away from that stuff either, but holds other possibilities within its expansiveness. With it, we also have a Springsteen album to remind us that, however distant it might seem, things don't always have to be this way.

11. The Rising (2002)

The Rising is an album loaded with symbolism for its place in Springsteen's career alone, not to mention its moment in a larger cultural context. Not an album of firsts, necessarily, but an album of "firsts in a while." Springsteen's first record of new material in seven years, his first rock album in 10 years, since Lucky Town in 1992. His first record since reuniting the E Street Band, which makes it the first record with the entire E Street Band since Born In The U.S.A. in 1984. Within his story alone, it's full of new beginnings.

The story goes that at some point within the first few days after 9/11, Springsteen sat at the water in Jersey and looked across to see the smoking wreckage at the southern tip of Manhattan. A man passed him, rolled down his car window, and called out, "We need you, man!" In that single anecdote, you get the whole idea that when Bruce & the E Street Band returned, it wasn't in the typical way of just another functioning artist. He was a beacon, a force that people hung upon to provide insight and guidance in one of our country's most traumatic moments (and what would go on to continue to be a traumatic decade).

It wasn't going to be a 9/11 record originally, and some of the songs date back before 2001. "My City Of Ruins," for example, was originally written about the dilapidation of Asbury Park, only to be re-contextualized to be about New York, and about America as a whole. But much of the record was written in the wake of the attacks, and whether you trace it back to the man calling from his car or to Springsteen having the strange experience of seeing multiple obituaries that noted how victims were huge fans of his, there's no real way The Rising wasn't going to be about 9/11. And in terms of his artistic development, this is integral. For better or for worse, Springsteen has now spent 10 years mainly being a chronicler in a way that's more specific to contemporary moments than his past work, but there's no question that taking on that mantle has provided the rush of inspiration that turned away from the mainly uninspired (and uninspiring) '90s and towards his prolific '00s. That starts with The Rising.

Despite it garnering critical acclaim and commercial success upon its release, I feel like whenever I hear people mention The Rising now it's not always in the most complimentary way. It might be a bit overlong, but its epic quality feels fitting for the moment at hand, both a fervent marker of Springsteen's return and an unrestrained attempt to capture the national climate. On that latter note, one of the perennial criticisms could be understood: The Rising does often traffic in vague universalities, especially when compared to the work of Springsteen's heyday. That sort of feels important and specific to the purposes of The Rising, though. Sure, there are a few songs that felt a little adult-contemporary or stock modern rock, and I can't really argue with that, though I don't dislike any of the material here. Maybe some fans are just fatigued — out of any of Springsteen's '00s releases, The Rising doesn't seem to have ever fell out of the live rotation, with its title track and "Waitin' On A Sunny Day" almost as likely to be played at any given show as "Born To Run" or "Dancing In The Dark."

Still, I can't help but be impressed with The Rising. Springsteen emerged out of the '90s with his band after an almost two-decade absence, and he emerged with a fully formed new sense of purpose and sound. In comparison to the '00s albums that followed, this feels like the E Street Band is involved, even though they're playing in an entirely different way than they used to.

And it's a crucial entry in Springsteen's catalogue for the radically different tone it has in comparison to most of his work. The Rising is outside of that realism/romanticism binary. It deals with a sober reality, and has sober realities within its songs, but its uplifting moments are not the moments of romantic escape from his past work, nor the blind optimism of Working On A Dream. Rather, they're hope at a time when our country needed it and when he as an artist had earned the right to seek it. In a way, that might suggest The Rising is rooted in its time. But that's where a vague universality, in a very rare instance, works. We'll always have the bleakness of Nebraska and, later, the anger of Magic and Wrecking Ball to remind us of the realities and troubles Springsteen is reacting to. The Rising doesn't shy away from that stuff either, but holds other possibilities within its expansiveness. With it, we also have a Springsteen album to remind us that, however distant it might seem, things don't always have to be this way.

10. The Promise (2010)

In the wake of the artistic triumph and sudden success of Born To Run in 1975, Springsteen found himself in a bind professionally and at a crossroads creatively. Embroiled in a lawsuit with his soon to be ex-manager Mike Appel, Springsteen was prevented from recording or releasing a new album. As a result, it would be 1978 before Darkness On The Edge Of Town arrived. Far from the unproductive stretch this appears to be on paper, the time period saw Springsteen entering his most prolific phase, the late '70s to early '80s heyday in which he produced multiple albums' worth of material that would be shelved, only to be later released in the four-disc 1998 collection Tracks and then, in 2010, with this, The Promise.

Specifically, The Promise arrived as a project interwoven with a slightly late anniversary package for Darkness On The Edge Of Town, and elucidates all the different paths Springsteen was considering in the strained interim between Born To Run and Darkness On The Edge Of Town. Rightfully realizing that Born To Run was the peak of what he could achieve with his earlier themes and sounds, Springsteen looked to new ideas, new structures. The difference between Born To Run and Darkness On The Edge Of Town is striking, and The Promise details all the things that could have been. We could have had an old-school R&B-inflected album if he'd gone the route of "Fire" and "Ain't Good Enough For You." There were chiming pop songs like "Gotta Get That Feeling," "Rendezvous," or "The Little Things (My Baby Does)" that suggested a far more romantic direction than the relative gruffness that eventually greeted listeners on Darkness. Tracks like "It's a Shame," "Come On (Let's Go Tonight)", and "The Promise" point towards the album that eventually came to be.

It may seem odd to be ranking what is basically a leftovers collection above full-fledged albums. The advantage of The Promise, though, is that unlike the more expansive Tracks it focuses on a very specific era, and manages to feel like a lost Springsteen album from the late '70s. A lot of the material here is just as good as stuff that made it on the actual albums, or the stuff that already saw release with Tracks. For me, more work of this caliber from Springsteen's peak era automatically pushes it past many of the official albums that were released before its eventual reveal. Even outside of its musical strengths, The Promise joins Tracks as crucial connective tissue for anyone interested in Bruce, fleshing out more of the musical and personal steps between some of his most iconic albums.

10. The Promise (2010)

In the wake of the artistic triumph and sudden success of Born To Run in 1975, Springsteen found himself in a bind professionally and at a crossroads creatively. Embroiled in a lawsuit with his soon to be ex-manager Mike Appel, Springsteen was prevented from recording or releasing a new album. As a result, it would be 1978 before Darkness On The Edge Of Town arrived. Far from the unproductive stretch this appears to be on paper, the time period saw Springsteen entering his most prolific phase, the late '70s to early '80s heyday in which he produced multiple albums' worth of material that would be shelved, only to be later released in the four-disc 1998 collection Tracks and then, in 2010, with this, The Promise.

Specifically, The Promise arrived as a project interwoven with a slightly late anniversary package for Darkness On The Edge Of Town, and elucidates all the different paths Springsteen was considering in the strained interim between Born To Run and Darkness On The Edge Of Town. Rightfully realizing that Born To Run was the peak of what he could achieve with his earlier themes and sounds, Springsteen looked to new ideas, new structures. The difference between Born To Run and Darkness On The Edge Of Town is striking, and The Promise details all the things that could have been. We could have had an old-school R&B-inflected album if he'd gone the route of "Fire" and "Ain't Good Enough For You." There were chiming pop songs like "Gotta Get That Feeling," "Rendezvous," or "The Little Things (My Baby Does)" that suggested a far more romantic direction than the relative gruffness that eventually greeted listeners on Darkness. Tracks like "It's a Shame," "Come On (Let's Go Tonight)", and "The Promise" point towards the album that eventually came to be.

It may seem odd to be ranking what is basically a leftovers collection above full-fledged albums. The advantage of The Promise, though, is that unlike the more expansive Tracks it focuses on a very specific era, and manages to feel like a lost Springsteen album from the late '70s. A lot of the material here is just as good as stuff that made it on the actual albums, or the stuff that already saw release with Tracks. For me, more work of this caliber from Springsteen's peak era automatically pushes it past many of the official albums that were released before its eventual reveal. Even outside of its musical strengths, The Promise joins Tracks as crucial connective tissue for anyone interested in Bruce, fleshing out more of the musical and personal steps between some of his most iconic albums.

9. Tracks (1998)

In an otherwise musically uneventful decade for Bruce fans, the end of the '90s saw the release of Tracks. Long known for writing way too many songs for any given album, Bruce had by then accrued something like 350 unreleased tracks in varying states of completion, as estimated by his longtime engineer Toby Scott. Sifting through all of it, they came up with the 66 songs that wound up comprising Tracks, aiming to sketch out the alternative history of his career. The final product was a mixture of B-sides from old singles, demos, songs that had previously only been heard live, songs that had been mentioned but never released, and some that had been, until this point, entirely unknown.

Given that it's made up primarily of Human Touch outtakes (yeah, the stuff that didn't make Human Touch), the fourth disc is pretty dispensable. The rest of Tracks, however, is essential listening. Unlike the focus of The Promise, which had an extra "What if?" factor of feeling like a standalone album, Tracks is a wide-ranging, overwhelming listen, less so for any curiosity factor (like "If they had put this on The River rather than ...") than for the sheer amount of amazing material that was never heard simply because it didn't fit quite right on the albums. It starts out slow, with some early solo performance tracks and then a smattering of early '70s outtakes like "Thundercrack" (long a fan favorite at shows) and "Zero And Blind Terry." Things get really crazy on Discs 2 and 3 when you realize there were essentially enough songs to have (multiple) entirely different versions of The River and Born In The U.S.A., and, most preposterously, you can picture how they'd still be classic albums.

That likely sounds hyperbolic, but I don't think it really is. Oddly, Tracks was one of the main releases that I first listened to when getting into Springsteen. To me, the infectious jangle of "Take 'Em As They Come," one of the great overlooked Bruce tracks, trumps almost anything that actually did make The River; the charge of "My Love Will Not Let You Down" blows right past Born In The U.S.A. material like "No Surrender." Those are just my personal, peculiar obsessions, but any given fan could list "This Hard Land," or "Janey Don't You Lose Heart," or "Don't Look Back," or "Loose Ends," or "Shut Out the Light," or "Rockaway The Days," or ... you get the point. There's a ridiculous wealth of material to dig into here, stuff I'd immediately recommend to a new fan sooner than half the albums Bruce has put out. It might be a bonus round, but like The Promise it deepens not only the narrative of Bruce's career, but also your appreciation for just how damn good of a songwriter the guy is. If any fanbase deserves an embarrassment of riches like this, it would have to be Bruce's.

9. Tracks (1998)

In an otherwise musically uneventful decade for Bruce fans, the end of the '90s saw the release of Tracks. Long known for writing way too many songs for any given album, Bruce had by then accrued something like 350 unreleased tracks in varying states of completion, as estimated by his longtime engineer Toby Scott. Sifting through all of it, they came up with the 66 songs that wound up comprising Tracks, aiming to sketch out the alternative history of his career. The final product was a mixture of B-sides from old singles, demos, songs that had previously only been heard live, songs that had been mentioned but never released, and some that had been, until this point, entirely unknown.

Given that it's made up primarily of Human Touch outtakes (yeah, the stuff that didn't make Human Touch), the fourth disc is pretty dispensable. The rest of Tracks, however, is essential listening. Unlike the focus of The Promise, which had an extra "What if?" factor of feeling like a standalone album, Tracks is a wide-ranging, overwhelming listen, less so for any curiosity factor (like "If they had put this on The River rather than ...") than for the sheer amount of amazing material that was never heard simply because it didn't fit quite right on the albums. It starts out slow, with some early solo performance tracks and then a smattering of early '70s outtakes like "Thundercrack" (long a fan favorite at shows) and "Zero And Blind Terry." Things get really crazy on Discs 2 and 3 when you realize there were essentially enough songs to have (multiple) entirely different versions of The River and Born In The U.S.A., and, most preposterously, you can picture how they'd still be classic albums.