Thanks to years of label drama and just the simple passage of time, it's easy to forget the various ways that Anne Lilia Berge Strand changed the way dorks on the internet listened to, and thought about, music. When Pitchfork named Annie's "Heartbeat" the #1 track of 2004, Scott Plagenhoef, then the site's editor in chief, placed it at the forefront of a "new wave of fluxpop," defining that term as "tracks with a pop sensibility and communicative, crossover potential that are nevertheless more often transferred via 0s and 1s than Hot 97s or Radio Ones." Annie had earned some level of actual pop stardom at home in Norway, but over here, she was a curiosity, and her brand of curiosity was suddenly a fascinating thing for critics like me. Thanks to MP3 spots like Fluxblog, a song like "Heartbeat" could catch certain American and British ears and go low-level viral, its slight dissonances suddenly feeling weirdly important. Annie might talk about Death From Above 1979 or whatever in interviews, but she had no overt indie influence in her music; it sounded like straight-up Euro-pop froth, and it still got over with people who'd subsisted on a steady diet of Modest Mouse in the years before. At the time, a friend sniffed that "Heartbeat" was no different from Britney Spears, but that wasn't right, either. It was a song, with no brash edge to it, about longing and loneliness, topics with (ahem) some currency for indie dorks, but that feeling was artfully rendered as frothy Euro-pop rather than guitars-plus-bleats. And the realization that a song like this could be transcendent led publications like Pitchfork to hire assholes like me (first track review: Lil Scrappy, "No Problems," August 2004) and to notice that maybe Britney also had some transcendent songs (like "Toxic," Pitchfork's #3 track of 2004). A song like "Heartbeat," besides being an on-its-own-merits great song, had a lot to do with creating the internet-indie universe that we currently occupy -- a world where I work for an ostensibly indie site like Stereogum and I've already posted two different Drake pieces this morning. Maybe you hate Annie for that. I'd understand. But she's still very, very good at making frothy Euro-pop music.

Britain's Richard X didn't produce "Heartbeat," though he did do "Chewing Gum," the nagging almost-as-great second single from Annie's 2004 debut Anniemal. And Richard X has had a pretty great working relationship with Annie ever since, peppering tracks on the two albums she did manage to squeak past the record-label shitheads who kept pushing back her release dates, and now he's the other half of Annie's new A&R (which, yes, fine, is an EP and not an album, but sometimes an EP really is the best album of the week). Like Annie, Richard X had a pivotal role in the critical legitimization of slick pop music. He made his name by creating the first and best big song from the early-'00s mash-up wave, throwing Adina Howard's ravenous "Freak Like Me" vocal over Tubeway Army's harsh and monumental "Are Friends Electric?" instrumental on the internet-hit "We Don't Give A Damn About Our Friends." Later, he turned that into an actual British #1 hit when the British girl group Sugababes sang those "Freak Like Me" vocals over that same Tubeway Army beat. He made a few other UK hits, too, for people like Liberty X and Kelis. Those tracks turned up on his sole album, 2003's kinda-compilation Richard X Presents His X-Factor, Vol. 1, a slept-on minor masterpiece of theory-driven pop music. "Into U," on which Jarvis Cocker softly croons over a cascading "Fade Into You" sample, is a mixtape classic from the last historical moment that couples were making mixtapes for each other. Richard X and Annie just make sense together, on a theoretical and a chemical level. They're two people who think hard about pop music, who know that pop music can make you feel things.

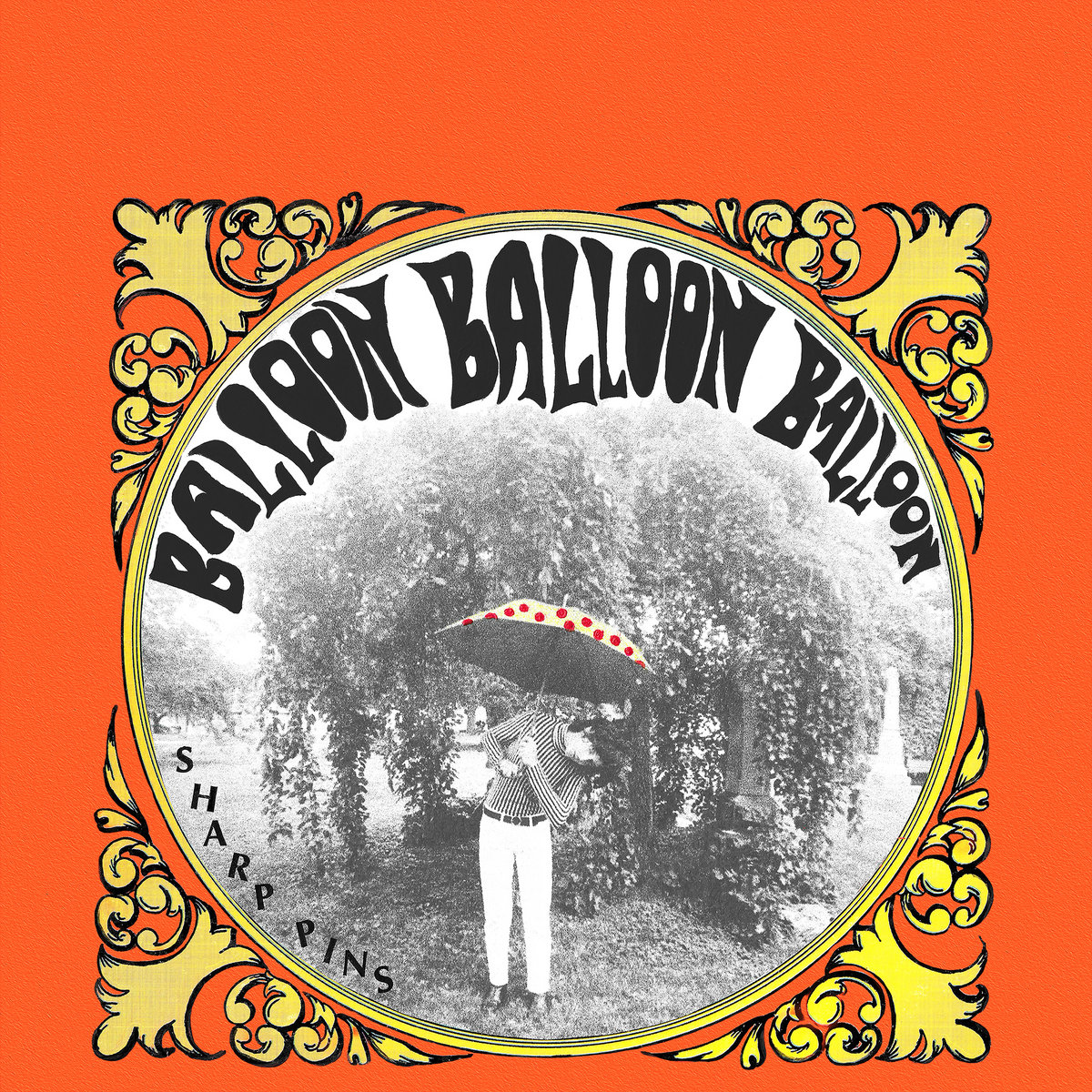

The liner notes to Richard X Presents His X-Factor, Vol. 1 (still waiting on that Vol. 2, homey) had all these fake 12" single covers, the brand-new Kelis track made to look like something you'd dug out of a thrift-shop vinyl bin, with the actual imprint of the record slowly wearing a circle into the cover art. This was a pop-music version of the fake film-crackles in Grindhouse: Unashamedly retro stuff done with such attention to detail that it never comes off as anything too obnoxious. That same aesthetic is still there on A&R, which self-consciously looks like something Robyn would've put out around the time she made "Show Me Love." (That whole throwback thing is even more evident in the "Back Together" video, which has clips of other fake videos from a fictional mid-'90s dance countdown show.) And the five song songs on the EP are extremely dialed into the dance-music virtues of that bygone era. "Invisible" has a skittering breakbeat and a dark synth pulse and a clumsy kinda-rap part; it's as German as a non-German song could possibly ever be. "Hold On" has all the dizzy sun-drenched thump of early St. Etienne. "Ralph Macchio" is even era-specific in the target of its lyrical desire, though judging by the brisk beeps of the track, Annie is crushing harder on the Macchio of 1992's My Cousin Vinny than the Macchio of 1984's The Karate Kid.

In this Idolator interview, Richard X claimed that the EP's sound is inspired by Deep Heat, a series of dance-music compilations that the British label Telstar released in the late '80s and early '90s. These were double-cassettes that they'd advertise on TV, and they made no distinctions between goofy money-grubbing dance-pop and underground acid-house. During the childhood year that my family spent in England, I bought the first of those comps, and it was awesome. Milli Vanilli's "Girl, You Know It's True" transitioned directly into a dark and heavy Detroit house track from Kevin Saunderson, and to a nine-year-old hearing all these sounds for the first time, that heterogeneous mix made totally sense. And you can hear the influence in the EP, in the way Annie and Richard X combine sugary pop hooks with deep, gratifying old-school house whumps and sonar pings -- a sound that seemed futuristic a long, long time ago.

But I wonder if Annie and Richard X realize that the era they're reviving here isn't the late '80s or the early '90s. It's the mid-'00s moment that they helped engineer, where all the received wisdom about dude-with-guitar primacy was starting to go out the window. It was weird to go back and read this thing I wrote about an Annie show at Mercury Lounge in 2006. I was honestly worried that the powers that be would wake up from their blissful nap one day and take all that smart music away, declare M.I.A. and LCD Soundsystem to be no longer cool, and that we'd all be sent back to white-growl purgatory. That didn't happen, and now we live in a world my bosses at Stereogum are actively asking me to write about K-pop or whatever. That world exists, in part, because of the smart, emotive, precise, canny disco-pop that Annie and Richard X were making together years ago. They're still making it, and it's still great. Respect is due.

Stream the A&R EP here.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Other albums of note out this week:

• Pond's fuzzed-out psychedelic stargazer Hobo Rocket.

• Moderat's heartfelt sputter-thump sophomore joint II.

• Blondes' trippy analog-electronic zone-out Swisher.

• Early-'90s shoegazers Medicine's reunion effort To The Happy Few.

• Empty Flowers' post-hardcore sophomore slammer Five.

• Explosions In The Sky & David Wingo's collaborative score to the David Gordon Green film Prince Avalanche.

• Pop. 1280's cantankerous, feedback-abusing Imps Of Perversion.

• Black Dice member Eric Copeland's solo bow Joke In The Hole.

• MINKS' jangly, synth-streaked Tides End.

• The Polyphonic Spree's dizzy, uplifting comeback Yes, It's True.

• Ultraísta's cleverly titled remix collection Ultraísta Remixes.

• R. Stevie Moore's cult-hero lo-fi compilation Personal Appeal.