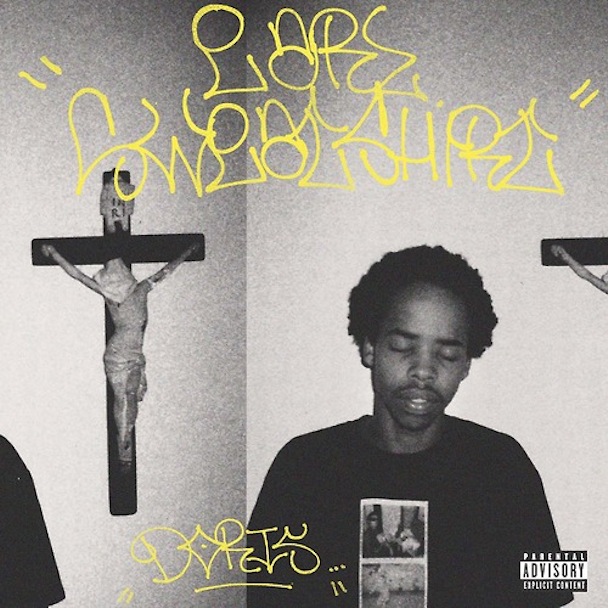

I'd been waiting for this moment for literally years: Earl Sweatshirt's triumphant return to the stage after being shut away in a Samoan reform school during his Odd Future crew's entire rise to fame and infamy. But there was nothing triumphant about the Earl I saw at the Fader Fort during this past March's SXSW. He looked nervous, withdrawn, confused at why the drunk free-wristband crowd wasn't losing it to his introverted new songs. He didn't perform "EARL," the song he recorded before his departure to Samoa, the one that practically caused riots when his disembodied, recorded voice would rap it at Odd Future shows. There was nothing neat about this Earl's narrative, and he'd been absent -- and, presumably, working on his own mental health -- during his entire ascent to fame. It would be hard to imagine anyone -- let alone a fatherless teenage kid with a troubled past -- adjusting gracefully to this sudden change of circumstances. And yet that same blinking insularity have now lead Earl to make Doris, the best Odd Future album since the last Earl album. Sometimes, insularity is your friend.

Earl's mother was the great villain of Odd Future's rise, the woman whose dream-squashing paranoia kept a great rapper from his faithful growing audience. And while the members of Odd Future remained taciturn on Earl's whereabouts, they seemed happy enough to play into that story. But the real story is a little more complicated. We still don't know why, exactly, Earl's mother sent him away, but he was rapping about pills and rape, and that's a legit cause for parental concern. As someone who's spent a bit of time around Lil Boosie, I can tell you that violent-rap child-stardom isn't exactly a recipe for healthy, happy adulthood, and so it makes sense to speculate that Earl's mother might've had some honest-to-god best interests in mind when she sent him away. Earl himself carefully picks through the debris of that period on Doris -- cursing the journalists who played digital gumshoe and tracked him down in that boarding school, admitting the difficulties in repairing his relationship with his mother, describing the headlong hooliganism that he experimented with before going to reform school. He seems to know that he was a broken kid, and he seems to be trying to be a better grown-up. Compare that to Earl's buddy Tyler, who seems to be stuck in a permanent state of arrested-development provocation, still spitting "faggot" on a 2013 album, unable to let go of the teenage rebellion that helped make him famous. Doris, by contrast, is a document of an insanely gifted kid trying to figure his shit out.

The album is also a dense tangle of words, a rappity-rap excursion that digs as deep into its maker's technical virtuosity as, say, a Joe Satriani album. For the first time since Good Kid, m.A.A.d. City, I find myself digging through lyrics on RapGenius -- not because I care what the chucklehead community there thinks, but because I have an easier time processing these lyrics if I can see them typed out, and because the lyrics actually seem worth parsing. Rap albums can be good for a lot of things, and Doris leaves a lot of those things out completely. There's very little songcraft here, hardly any hooks, no real catharsis, not much textural variation. There's not a single anthem here, nothing that will induce a rap-hands car-radio shout-along unless you're in a very particular mood. Earl raps everything in an inward half-swallowed monotone, and RapGenius also helps with the album because it can be hard to hear the actual words without it. Earl produced much of the album himself, and he favors a digital fog, a jazz-based musical palette that gives his voice space but never demands attention. "Hoarse" has production from the Toronto jazz trio BadBadNotGood, and, bless them, they seem to be reviving the knife-edged trip-hop of Tricky's Pre-Millenial Tension. The album's first verse comes from the total-unknown SK La' Flare, and Earl gives plenty of mic time to his friends, almost using them to fill up the time while he gets his thoughts together. Some of those friends, like Vince Staples on "Hive," even make as much of an impression as Earl himself. And when Tyler shows up in his usual barking-demon form, he briefly kills the album's heavy-nod vibe.

But despite all the extra voices, this isn't really an Odd Future album, or an Earl-and-friends revue. It's a knotty and personal rap-as-therapy piece of work -- an In Utero from a guy who made his Bleach but skipped the Nevermind. Throughout the album, he namechecks Gil Scott-Heron as often and as happily as he did Eminem on EARL, and that's telling. "Chum" is both the first single and the deepest track, the one where Earl most plainly attempts to figure out the impossible arc of his own young life. "Sunday" is an actual relationship-song, with Earl and Frank Ocean trading verses about trying to keep the people who makes them happy, even as they know their lives make them totally unavailable to those people. On "Burgundy," Earl practically spells the album's entire theme out -- "Nigga, I'm 'bout to relish in this anguish" -- before threatening kamikaze car-attacks and name-checking Clark Gable in The Misfits.

And really, those allusion-heavy asides are as central to the album as the actual emotional stuff. Earl isn't trying to present himself as some struggling saint here; there's too much talk of bongs and blowjobs for that (though I'm delighted to report that he's ditched the rape/homophobia/kidnap-your-daughter stuff). There's joy to be heard on Doris, and it's the joy of rapping -- of putting words together and being really good at it. Throwaway lines are so perfectly, awkwardly constructed that I just want to stare at them for a while: "Bars hotter than the blocks where we be at / Stuntin', these niggas gon' flop like Divac"; "In the land of the rent-less, stand with my chips in a stack and grin, fuck 'em." Sometimes, those lyrics are so tortured and dorked-out -- "Hat never backwards like the print off legit manga" -- that you can't help but remember that this is a kid, a really smart one who maybe has too much fun sometimes in showing how smart he is. (Once upon a time, no major-label rapper would admit to reading Japanese comic books, and here we have one who not only reads them but draws elitist distinctions between the ones that read forward and backward.) And sometimes, as on "Hive," the tiny shards of lyrical brilliance -- "desolate tenements, tryna stay Jeckyll-ish" -- match perfectly with the tingly, evocative beat and the deep-in-the-pocket delivery, working on the same uncanny plain as, say, Prodigy's stab-your-brain-with-your-nosebone threat on Mobb Deep's "Shook Ones, Pt. 2."

Prodigy was 19 when he wrote that line, just like Earl is now. And just like Prodigy, Earl's mind is old. That's good. He'll need an old mind to navigate the absurd fame-world he found when he came home. And the dark, heavy, introverted Doris is the best album we could've reasonably imagined he'd make right now. I hope that, as Earl keeps rapping, he finds some of the breezy fun that rap can bring even when it isn't just words on words. But Earl's got a lot to work through right now, and we're lucky that we get to hear him do it.

Doris is out 8/20 on Tan Cressida/Columbia. Stream it here.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]