Neil Young Albums From Worst To Best

Aliens land. They’ve traveled from some distant planet with a specific mission: to find out what this ‘rock and roll’ stuff is all about. Through some curious coincidence, they find you. “What is rock and roll?” they demand, rayguns drawn. You begin to sweat. Still, there is really only one question you need to ask yourself:

“Which Neil Young album do I play them first?”

This is no hyperbole; Neil Young is the personification of rock and roll in human form. From his humble beginnings as a surf rocker in the Squires to his tenure in Hall Of Fame acts Buffalo Springfield and Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, to his most recent blitzkrieg Psychedelic Pill, Neil has spent a career as the embodiment of artistry despite fierce resistance. This iron-willed devotion to the Muse has not come without a price, however: While Neil’s successes have mostly flown in the face of prevailing music biz wisdom, his uncompromising nature has earned him almost as many failures, failures that should have sunk him several times over. His unpredictability and star-chamber business practices have often made him a pariah; his impulsive spirit and mood swings would frequently estrange his fellow musicians and most ardent supporters. Even more than Dylan, Neil Young has made a career of being consistently inconsistent.

As an architect of what we now consider ‘underground music’ there is no peer: For every Great Indie Moment of the past thirty years, there is a Neil Young song correlative. Wanna hear ground zero for Mercury Rev’s Deserter’s Songs? See “Journey Through The Past.” The raw-nerve humanity in the songs of Jason Molina? Check out “On The Beach.” The primary influence on J Mascis’s wild, feedback-laden guitar playing, or his reedy, cracked vocal style? That’d be “Cortez The Killer” and “Mellow My Mind,” respectively. Alt country? “Harvest.” I could do this all day. Of course, it works both ways: Neil Young’s decision to release 1991’s Arc, a 35-minute collage of feedback and noise, seems directly inspired by his run-ins with Sonic Youth, while the Pearl Jam-assisted Mirror Ball would find the newly-sired Godfather Of Grunge an awestruck but reluctant don of the alternative rock revolution.

Neil Young has never lent his music to a commercial. He was the Canadian hippie that publicly supported Reagan (despite the fact that he was not eligible to vote), only to record an entire album arguing for the impeachment of George W. Bush. He vainly made movies that made Cocksucker Blues look like Double Indemnity. His autobiography depicts a man more interested in model trains, vintage cars, and cutting-edge technology than his legacy as a rock star, which seems to bore and trouble him.

This, at least, is consistent: As early as 1966, the reluctant star penned “Out Of My Mind” for Buffalo Springfield’s debut album, a song containing the lyrics “All I hear are screams/ from outside the limousines/ that are taking me out of my mind.” He introduced himself to the world with songs about epileptic seizures, tormented small-town girls, and the rent that always seems to be due. His peers may have been enjoying the nectar of flower power, but Neil’s acute perception allowed him to see the darkness just below the surface.

It is easy to view Neil as a cranky contrarian who takes his gifts and fortunes for granted, but this is an oversimplification. It is equally tempting to define him alongside similarly protean artists from Bowie to Gaga, but this, too, is specious. The genre experiments of other artists often indicate an identity crisis, or an attempt to recreate oneself in the hopes of appealing to increasingly fickle market forces. It could be argued that Neil’s shape-shifting is motivated by the exact opposite reasons: trends, expectations, and market forces be damned, he doesn’t feel like making another country-rock record right now. Whether his imagination leads him to Greendale or to goldrush, it’s all the same to Neil Young. This is why even his most seemingly impersonal, comically overambitious leaps of faith contain, at their core, an honesty — a humanity.

His music may be frequently peevish and outwardly rebellious, but at heart, Neil’s a moralist. His fierce loyalty to talented-but-toxic characters like Bruce Palmer, Rusty Kershaw and Danny Whitten is an example of a probity that undermines a reputation for hardness. Other examples can be found within the songs themselves, full of lessons: Sooner or later it all gets real. Only love can break your heart. Don’t be denied. Don’t wait till the break of day. Time fades away.

It has become customary when introducing Counting Down pieces to note that there is no ‘worst’ album by the featured band, acknowledging that a great artist’s relative failures are often redeemable within a greater context. In previous entries I have written on Sonic Youth and Drive-By Truckers, among others, this has been true and I stand by it. It is not true for Neil. I won’t claim that the bottom five entries on this list are complete turkeys, but they’re certainly pretty close.

Still, I feel I must disclose that Neil Young has created some of the most important music of my life. Since the release of Freedom in 1989 and subsequent concert at Jones Beach that same year, I have unfailingly purchased every Neil Young record on the Tuesday of its release; I have done this even as the digital age has allowed me to audition lousy albums like Greendale and Fork In The Road beforehand. A tattoo on my right wrist reads ‘WWNYD,’ elevating Neil to the status of Jesus Christ, and a promotional poster of Neil at Massey Hall hangs over my writing desk. In some ways, this makes me both the best and worst person for the job of ranking Neil’s albums; I am, and shall always be, a Neil Young apologist.

Living With War (2006)

Manager Elliot Roberts told Young's controversial biographer Jimmy McDonough "If (Neil) watches tv on the road and there's a CNN special on Bosnia, Neil wants to do a record and a benefit within two days." This same impulsiveness sinks Living With War, a joyless album of vapid political screeds that makes Country Joe McDonald sound like Cornel West. Coming on the heels of the also-political Greendale, Living With War finds our hero in "hippie dream" mode, struggling to conjure anything beyond raw passion; there's even a song called "Let's Impeach The President." Written and recorded over a period of nine days, the album is a classic rush job; it bleats its message but forgets to give a shit about the music. In a career marked by strange detours and artistic decisions bordering on the surreal, this one isn't even wacky enough to merit a laugh.

Fork In The Road (2009)

A friend recently argued that even Neil's failures are never boring. He's almost right, as evidenced by several compelling failures on this list, but Fork In The Road, a concept album about the electric car, belies this bold claim. What might have been an intriguing concept album about America's overreliance on oil, the short-sightedness of shady tycoons, and sheeple resistant to change, turns out to be, well, mostly a bunch of songs about electric cars. The music makes even less of an impression than the lyrics, and it's hard to imagine someone choosing to listen to Fork In The Road over pretty much any other Neil Young record. Even the acoustic numbers fall flat: despite a classic Badlands melody and swooping pedal steel, "Light A Candle" is a yearbook quote masquerading as a song, while the gospel-leaning "Off The Road" reaches for poignant and lands at puffy. "It's all about my car," Neil repeats in the listless and vaguely rap-damaged "Cough Up The Bucks." You can't say he didn't warn you.

Americana (2012)

2012: Word on the street was that Toast, the unreleased Neil Young album that has been for years the subject of Smile-like levels of conjecture among Neil diehards, was finally being released. Neil had done his part in stoking the fires of his lunatic fringe, claiming in a 2008 interview with Rolling Stone that Toast had "everything that the best Crazy Horse albums ever had." Imagine the groans when Americana, an album of public domain songs rendered in the Crazy Horse style, was released instead. While it's difficult to imagine that anyone was dying to hear Crazy Horse tackle cornball classics like "Oh Susannah," "Jesus' Chariot (She'll be Comin' Round The Mountain)," and "Clementine," the decision to release this inconsequential collection of singalongs in lieu of Toast seems especially malicious. It doesn't help that the songs plod along interminably, offering little in the way of nuance; even the usually frothing Crazy Horse is toothless here, as if they're straining to read the chord changes from a dry erase board across the room. Still, the album is not a total wash: many of the seldom-heard additional verses of these perennial favorites are featured here, and if you only know these tunes by the sanitized versions you sang in kindergarten, expect some surprises. Also surprising is the unexpected cover of British national anthem "God Save The Queen," which cleverly caps the album with a nod to our English forebears. Still, whether viewed as a dilatory cockblock or as another forgettable Neil Young album, Americana remains, at best, a trifle; at worst, a screaming bore.

Greendale (2003)

Greendale is Neil's first in a series of increasingly uninteresting concept albums (see entries #33-#35) released since the new millennium, and to call it the best of the bunch is to damn it with only the faintest praise. Long on social commentary but short on ideas and songs, Greendale — the album as well as its accompanying book, film, and (gulp) comic book — is half-baked, ponderous, and dull when it isn't downright obnoxious. Submerged within the eighty minutes of this minefield is some quality material, but slogging through the morass to get to the primal, groovy "Double E" or the oddly Yo La Tengo-sounding "Bandit" hardly seems worth the trouble. Most rock operas are messy, incoherent and / or overblown, but, mercifully, very few feature shrill bullhorns. Avoid.

Everybody's Rockin' (1983)

With all due respect to record label-agitators Prince, John Fogerty, and Van Morrison, Neil Young's Everybody's Rockin' remains the most notorious nose-snub in rock and roll history. A 25-minute rockabilly album recorded in response to David Geffen's insistence that Neil make a proper "rock and roll" record following the artistic and commercial disasters of his previous three Geffen albums, this vindictive tribute to 50s rock and roll is pure period piece, one that reaches Christopher Guest-levels of comic surrealism. Neil even dresses the part, appearing on the cover looking battle-ready in conspicuous pompadour and pink suit. While the album is certainly evidence of Neil's continued artistic floundering, it also proves he hasn't lost his sense of humor. The most compelling aspect of Everybody's Rockin' is Neil's inability to actually pass himself off as a rock and roll playboy, which only emphasizes his strangeness: In the accompanying music video for "Wonderin,'" Neil plays a rockabilly heartthrob but looks more like the snarling, smirking psychopath depicted by Jack Nicholson in The Shining, far more like a man who'd threaten to bash his buttercup's brains in than ask her to go steady. The album does contain some decent material, maybe in spite of itself: "Wonderin'" is best heard as a live version that appears on the 2006 archival release Live At The Fillmore East, but the tidy, swinging album version is almost as good; and if you can get past the conspicuous digital reverb of "Cry Cry Cry," you might mistake it for a lost Sam Phillips joint. Nevertheless, Everybody's Rockin' mostly deserves its reputation as one of Neil's least essential LPs. It would also result in a 3.3 million dollar lawsuit: Geffen claimed Neil was making albums "uncharacteristic" of Neil Young. Ever refractory, Neil countersued for breach of contract. Seems to me if Geffen didn't consider an album like Everybody's Rockin' exactly characteristic of this most impulsive and disputatious rock star, one who has never abided a kibitzer no matter how rich or powerful, he clearly wasn't paying close enough attention.

Mirror Ball (1995)

Mirror Ball, an ill-conceived collaboration teaming Neil Young with grunge stars Pearl Jam, was timed to capitalize on Neil's sudden popularity among the burgeoning alternative nation, who identified with the Godfather of Grunge's occasionally disaffected worldview and fondness for plaid shirts. Neil has performed with many backing bands — some great, some less so — but Pearl Jam may go down as the worst. Rather than push the momentum or try to tease at wresting control from their leader, as Crazy Horse is wont to do, the members of Pearl Jam seem to take their auxiliary role a little too seriously; the younger band sounds frequently exerted following their hero through these half-written tunes. That is, except for drummer Jack Irons, who overcompensates, keeping time as if he's sitting in with the Talking Heads. Mirror Ball isn't all bad: dirge-like opener "Song X" provides enough minor key ill-ease to hint at what might have been had Neil teamed up with a band that better defined the era like, say, Unwound, while "I'm The Ocean" imagines Dead Moon draped in mohair. Worth a purchase if discovered in the used bin, where it can always be found.

Old Ways (1985)

This head-scratcher of an album finds our hero suddenly patriotic, and though its roots are in folksy classics like Comes A Time and Harvest, with which the album shares many musicians, the hokey material on Old Ways doesn't come close reaching the vaunted heights of those earlier works. Another large problem is that Old Ways would be the first all-digital Neil Young album, a trend that would continue throughout the decade, until a swift 180 in the nineties. Pandering to flyover country with patriotic clichés and vaguely jingoistic platitudes, not even appearances by Waylon and Willie can legitimize this drab, formless album. Several songs from Old Ways would appear over 25 years later, on 2011's archival release A Treasure, which documents the Old Ways tour and finds Neil backed by a short-lived band of session musician royalty called The International Harvesters. The hot-shit versions of "Bound For Glory" and "Get Back To The Country" found here are almost enough to pardon Old Ways. Almost.

Landing On Water (1986)

Following Geffen-frustrating genre experiments like Everybody's Rockin', Trans and Old Ways, Landing On Water was Neil's return to hard rock -- sort of. Backed by a band of studio musicians and produced by the untested Danny Kortchmar, Landing On Water is also the first album Neil would make with engineer Niko Bolas, who would preside over the next few equally difficult albums. One of the only modern Neil Young albums to feature overdubbed lead vocals, Landing On Water is a claustrophobic, digital mess of synth bass, click tracks and sound effects that dated the album before it was even released. Created, inexplicably, by recording a full band overdubbing atop Neil's skeletal acoustic guitar and drum machine demos, the album's monstrous, gated drums frequently drown out the guitars, making the record sound both heavy and neutered simultaneously. Somehow, the results aren't wholly objectionable: "Pressure" isn't too far from the sort of motorik post-punk on which Spoon would build their reputation, while the David Crosby-blasting "Hippie Dream" finds Neil caustically dismantling his friend — "Another flower child goes to seed / In an ether-filled room of meat-hooks / It's so ugly" — like Lennon going for McCartney's throat on "How Do You Sleep?" And yet, the most positive thing to say about the much-despised Landing On Water is that it isn't a fiasco. Neil himself was not as charitable when, a year later, he foreshadowed a future song title in his summation of the album to British radio deejay Dave Ferrin: "It's a piece of crap."

Prairie Wind (2005)

A sort of unofficial sequel to 2000's superb Silver & Gold, Prairie Wind similarly recasts old songs as country-rock numbers in the Harvest Moon mold. Neil has done the 'aww shucks' bit better at least three different times, but if you're one of those people who can't get enough of Neil's nostalgic rambling and overproduced country rock, Prairie Wind delivers. Following as it does Neil's 60th birthday, which arrived with a brain tumor and the death of his father, the maudlin mood of Prairie Wind is perhaps defensible, even as it veers perilously between profundity and schwarmerei. The only unforgivable number is the baroque "When God Made Me": Built on the sort of rococo arrangement that resulted whenever Jack Nitzsche meddled with a Neil Young song, this turgid album closer competes with "Such A Woman" and "Let's Roll" for Neil's most embarrassing song. The rest of the album is all bucolic and loamy atmosphere that only lets up when something unexpected occurs, like a reference to Chris Rock, but such moments are scarce. Mostly, Neil just sounds resigned, resting comfortably.

Broken Arrow (1996)

Reeling from the death of David Briggs, his foil, frequent producer and close friend of 27 years, Neil rushed out Broken Arrow, an album that sounds more compulsory and half-assed with each passing year. Though over half the tunes exceed five minutes, it's nevertheless difficult to imagine these perfunctory plods exciting fans of Crazy Horse's more adventurous jamming. Even worse is a cover of Jimmy Reed's blues classic "Baby What You Want Me To Do," included here in such gauzy low fidelity it would send even Bob Pollard scurrying for the Hear-Os. The pensive and acoustic "Music Arcade" is the only saving grace, helping the rest of this bad medicine go down. Perhaps Neil was preoccupied: his soundtrack to the Jim Jarmusch surreal western Dead Man had been released just five months earlier. This may excuse any infractions committed by the largely forgettable Broken Arrow: Dead Man, though an outlier inappropriate for inclusion on a list ranking proper studio albums, remains the more crucial 1996 Neil Young release, containing noisy guitar improvisations that sound like Six Organs of Admittance impersonating Bill Frisell.

Are You Passionate? (2002)

Recalling 1988's similarly unexpected This Note's For You, Neil's R&B-laced Are You Passionate? finds him backed by no less a formidable band than Booker T. and the M.G.s. The result is long-winded and weird, but it contains some great, often overlooked tunes: the haunting "Mr. Disappointment" could have fit snugly on Sleeps With Angels, while "Goin' Home," a lone number performed with Crazy Horse, provides the trademark chug the rest of Are You Passionate? lacks. The album also features what might top a list of Neil's Very Worst Songs, the manipulative and idiotic "Let's Roll," written, in what could only be excused as a delusional patriotic fever, in response to the bombing of the World Trade Center. This aside, Are You Passionate? is an enjoyable, if dispensable, late period entry.

Chrome Dreams II (2007)

Referencing a famously aborted Neil Young album (and subsequent bootleg) was a clever move, but to consider the name-check anything more than an impish wink at his fanbase is to give Neil far too much credit for giving a rat's ass what his fanbase thinks. Not the return to form its title suggests, Chrome Dreams II begins brilliantly, but ultimately fails to leave much of an impression; its second half, in particular, is full of barely-there songs that never seem to gel. Knowing Neil, this may be the point, as Chrome Dreams II plays like a fan-assembled bootleg, with little in the way of an overarching theme. Still, the Harvest Moon-worthy "Beautiful Bluebird" kicks things off beautifully; "No Hidden Path" is molten and mystical; and the long-but-glorious "Ordinary People" recalls some of Dylan's eighties masterpieces. These three — which, taken together, are longer than several entire albums in Neil Young's catalog — are alone worth the sticker price.

Life (1987)

Unfairly lumped in with its inferior predecessor Landing On Water, Life may be as boxy, gelid and oppressive as the rest of Neil's Geffen albums, but it also has something those albums lacked: good songs. Ignore the digital sheen and silly sound effects and the live-recorded Life displays much of the old Neil sparkle. The irresistibly moronic "Prisoners of Rock and Roll" offers a sneak peek at the sort of gargantuan power-garage of Ragged Glory; the slow dance-ready "When Your Lonely Heart Breaks" recaptures old songwriting glories despite production that sounds like something rejected by Richard Marx; "Long Walk Home" imagines Phil Ochs confronting MIDI; and "Inca Queen" boldly attempts to introduce New Age to new wave. The album's not-so-subtle cover art depicted Neil behind bars, a transparent jab at his increasingly adversarial label and its head honcho David Geffen. Emancipation, however, was imminent: upon the release of Life, Neil Young would be unceremoniously dropped by Geffen, leaving five of rock and roll's oddest and most controversial albums in his wake. But if Neil's own discography is his greatest enemy, as he has repeatedly theorized, Life poses an interesting question: If this perfectly decent synth-rock album had been released as a debut by an upstart, rather than the work of a prestige artist, would the response have been different?

Hawks & Doves (1980)

Like Rust Never Sleeps and American Stars & Bars before it, Hawks & Doves is an album that uses the two sides of an LP to showcase two different sides of our ever-eclectic hero. Unlike those previous two entries, however, the grab-bag approach of Hawks & Doves doesn't make for an easy listen. Side one, mostly made up of seemingly incompatible flotsam from the aborted Homegrown album, features at least one winner in the form of the quixotic "The Old Homestead," while the intriguing-but-overrated "Captain Kennedy" provides another minor highlight. The album was released on November 3rd, 1980; the following day, Ronald Reagan would be elected President of the United States, and Hawks & Doves' thorny, cranky second side of down-home heartland horseshit portends all kinds of doom by association.

This Notes For You (1988)

Reinventing himself as a bluesman named Shakey Deal, Neil Young commemorated his vow renewal with Reprise with a new band and a new attitude. Complete with a 6-piece horn section, This Note's For You would garner more acclaim — and notoriety — for its title track's anti-corporate message and subsequent Julien Temple-directed music video than for anything else on this difficult but undervalued album. Though the flat recording does Shakey Deal and his band no great favors, a handful of tunes cut through: The churning juke joint nod-out that is "Coupe De Ville" recalls the wall-gazing desperation of On The Beach; the soft rock horns on the lonesome-sounding "Twilight" are deliciously incongruent with Shakey's stinging, scalding-tube guitar tone; and "Can't Believe You're Lyin'" is a scarecrow of a song that imagines a Narcotics, Anonymous meeting disrupted by an impromptu concert by Robert Jr Lockwood. All the while, The Bluenotes — actually a random assortment of allies, studio hacks and Neil regulars — provide crests of just enough airbrushed nightclub schmaltz for their zooted leader to surf over. MTV initially banned Temple's controversial music video, then honored it with a Music Video Of The Year award several months later, foreshadowing the kind of fair-weather corporate revisionism Wilco would famously endure at the hands of their label over a decade later. This Note's For You is a good album, and one of Neil's most unfairly maligned.

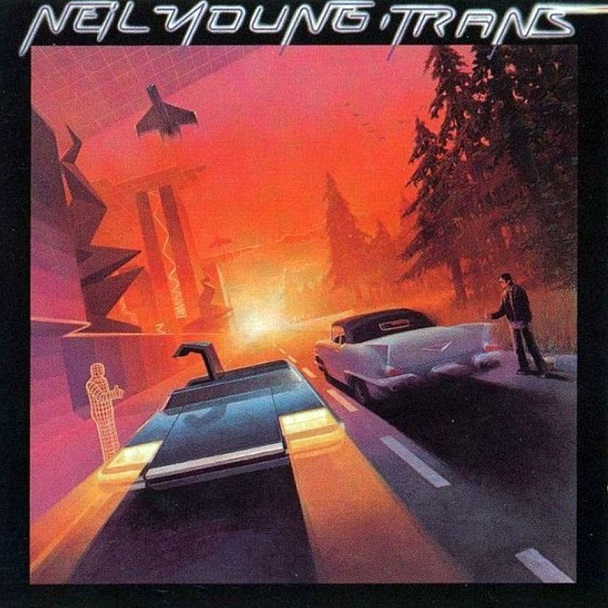

Trans (1982)

Trans fails not because of what it is but what it is not. The album's reputation as a catastrophic failed experiment has in recent years been disputed by revisionist hipsters, who cite it as a precursor to minimal wave, techno, and countless electronic music subgenres. If only that were true. Truth is, Trans could have been such a defining, trendsetting album, but Neil's inability to wholly commit himself to the experiment results in an album that sounds indecisive and occasionally dilettantish. Struggling to communicate with his mostly non-verbal son, and under the influence of Devo, Neil immersed himself in a world of synthesizers, vocoders and synclaviers. Total immersion would have resulted in an album far ahead of its time, for much of Trans is incredibly prescient: the fantastic "Computer Age" still has no sonic analogue anywhere in music; the proto-electro "Sample And Hold" invents Daft Punk; a re-recording of "Mr. Soul" sounds like Thomas Dolby off the meds; and the gorgeous "Transformer Man" proves that Grandaddy was not the first to outfit artificial intelligence with a heart of gold. Unfortunately, the spell is broken by three songs from the aborted Island In The Sun album that bear little of the technological curiosity found elsewhere. Still, it's true that Trans' reputation could use some reevaluating; it is widely misunderstood as another vindictive raspberry by Neil the provocateur, but to compare it to pranks like Everybody's Rockin' is to ignore its deeply personal nature. It is a record about failure to communicate, and Neil, through gadgetry, articulates this failure with the same humanitarian depth as that found on his finest love songs.

Psychedelic Pill (2012)

2012's double-disc Psychedelic Pill contains long-form jams recalling Zuma's virile sprawl and finds Neil Young and Crazy Horse revitalized; the band hasn't sounded this lively in years. The two discs fly by: even the 27+ minute opening track, "Driftin' Back," which finds Neil free-associating about hip hop haircuts and fine art, seems oddly brief. It sets the tone for an excellent double LP: thick tussles of fuzz permeate the irresistible "Ramada Inn," an idiosyncratic tale of empty nest syndrome; "For The Love Of Man" finds Neil vocally aping his hero Roy Orbison and guarantees goosebumps; and "Walk Like A Giant" features some of Neil's most raucous, twisted guitar playing in years, hinting at the possibility of a few Acid Mothers Temple discs in the glove compartment of the Lincvolt. In a revealing 1985 appearance on New Zealand television, Neil explains Crazy Horse's appeal: "Crazy Horse is a very simple sound. It's mostly emotional. It's not very technical." On Psychedelic Pill, Neil reminds us, and maybe himself in the process, that sometimes a very simple sound is all a giant needs.

Le Noise (2010)

Le Noise pairs Neil with vibe-master producer Daniel Lanois, resulting in one of the most richly idiosyncratic albums in his vast catalog. Lanois' fingerprints are all over Le Noise, and his contribution, more collaborative than facilitative, makes the record. Neil's heavily treated acoustic guitar, sopping wet with all manner of effects, adds new and previously unheard colors to his sonic palette. Rich echo and bold sonic effects augment even the lesser tunes, lending them a moody weight that seems almost focus-grouped to entice the lava lamp-gazing unemployables in Neil's fanbase. Neil rises to the occasion with a solid batch of stormy, hypnotic songs, two of which are canon-worthy: the eternally-bootlegged and autobiographical "Hitchhiker," an unflinching laundry list of Neil's drug experiences, and the haunting and detail-rich "Peaceful Valley Boulevard," as gorgeously downcast as anything Neil ever committed to tape.

Neil Young (1968)

Produced by his new friend David Briggs, Neil's debut is unlike anything else in his catalog. The infamous stickler nevertheless lacked the music industry clout to mastermind his own debut, resulting in an overproduced, too-many-chefs type album that nevertheless contains magic in abundance. Recorded at several different studios and meticulously labored over, Neil Young is mostly what you'd expect a solo album by Buffalo Springfield's resident weirdo to sound like. Powerful downers like "The Old Laughing Lady," the epic "Last Trip To Tulsa," and the vaguely Bee Gees-y "The Loner" are logical extensions of Neil's Buffalo Springfield contributions like "Flying On The Ground Is Wrong" and "Nowadays Clancy Can't Even Sing." Pianist Jack Nitzsche co-produced three songs, adding strings and bombast that foreshadow future collaborations like "A Man Needs A Maid," while Ry Cooder adds stock guitar licks throughout. Despite the meddling and the polish, or because of it, the album sounds incredible; play a vinyl copy on a decent turntable and you'll never look at your iPod the same way again. Neil would do an almost complete about-face on his next album, releasing an album as reductive as Neil Young is glossy, but the debut remains one of the more telling snapshots of a fine artist on the cusp of a greatness.

Ragged Glory (1990)

Older would-be-hits like the Chrome Dreams-era "White Line" (originally titled "River Of Pride") and "Country Home" are given a second life amongst other primitivist yowls on the raucous Ragged Glory, a relatively loose and joyously uncomplicated album in the vein of Zuma. Half of the songs here exceed five minutes, and two are over ten; clearly, Crazy Horse came to jam. Occasionally, things get a little too ragged, as on a tone-deaf cover "Farmer John," but it's hard to begrudge Neil a victory lap with his old comrades after what many considered a career-redeeming album in the previous year's Freedom. The songs are mostly terrific: "Country Home" finds Neil The Naturalist acknowledging the style of city life but opting, as always, for the peace of mind associated with more bucolic purlieus, while Crazy Horse sounds possessed on the mesmerizing "Over and Over" and punk-fugly "Fuckin' Up"; these and other songs are pleasant reminders that Crazy Horse's block-headed garage pummel will always be the most natural musical correlative to Neil's lyrics, his voice, and his vibe. In a rare interview with CNN to promote the album, Neil concurs: "I think the purest essence of my music…is the stuff that I do with Crazy Horse."

Silver & Gold (2000)

Melancholic, wistful, and overly sentimental: if these sound like descriptors interchangeable with at least four other Neil Young albums, fair enough. But Silver & Gold, Neil's first album of the new millennium, is his finest collection of such songs since Harvest Moon. Neil has written nostalgic tunes before, like Harvest Moon's "One Of These Days" and Ragged Glory's "Days That Used To Be," songs full of loose-end tying, let-bygones-be-bygones lyrics that left one wondering if Neil was twelve-stepping, dying, or both. On Silver & Gold, these earthbound acknowledgements of mortality constitute a theme, and Neil has rarely written so fluently of friendships, family, and the passage of time. The romantic title track, which dates back to at least 1985, is a clear highlight, as is the deeply penetrating "Razor Love," but the lean Silver and Gold is truly without a weak track. The musical accompaniment is appropriately easy-breezy, from the mellow gait of the rhythm section, which comprises the legendary Jim Keltner and Donald "Duck' Dunn, to Ben Keith's swooping pedal steel and Spooner Oldham's exquisitely minimal electric piano. If it all sounds a bit stodgy, give it another chance; Silver & Gold is one of Neil's most beautiful and consistently rewarding albums.

Re*ac*tor (1981)

…or, "Neil checks out." Written and recorded shortly after his son Ben was diagnosed with cerebral palsy, Neil allegedly zombie-walked through these sessions, preoccupied with a unique and intensive 'patterning' program for Ben that required his constant, round the clock attention. Taking this into account, it's remarkable how compelling Re*ac*tor is despite the eternally micro-managing Neil's inability to be emotionally or mentally present. This context may also excuse, or even validate, the lyrics on the album, which read like afterthoughts, as well as the playing of the historically ragged Crazy Horse, who perform like metronomic robots. The tempo on low-IQ jammers like the dense "T-Bone" hints at frustration and claustrophobia, while other songs, like the suitably locomotive "Southern Pacific," the record label brass-baiting "Surfer Joe and Moe The Sleaze," and the should-have-been-a-masterpiece "Shots" make Re*ac*tor more a missed opportunity than a failure. The rubric on the back cover, rendered in Latin, is nothing so obscure as the Serenity Prayer, popularized by its adoption by Alcoholics Anonymous, but obviously holding a different meaning for the troubled but longanimous Neil. With its stiff tempos and monotonous minimalism, Re*ac*tor is Neil's Accidental Krautrock album, which alone should entice immediate reevaluation.

Sleeps With Angels (1994)

Oversold at the time of its release as an elegy for recent suicide Kurt Cobain, this solemn, affecting album is denied a higher ranking due only to bloat: omit a third of Sleeps With Angels, and it's a top ten classic. The overarching mood of the album may be melancholy, but the sounds are spontaneous and inspired. The album opens with vibraphone and saloon piano on the dramatic "My Heart," but this proves an outlier; from here, the band rarely lets up the noir-ish grind. This is not to say Sleeps With Angels has the same lovably tossed-off quality of previous Crazy Horse LPs; piano, acoustic guitar and even flutes find their way into the mix this time around. The increased production value doesn't spook the Horse, however, but proves an asset; even the band's abundant background vocals sound well considered for a change.

The songs are sharp and somber; that Neil still possesses the ability to produce songs of such grainy realism only two years after the pastoral and hushed Harvest Moon is a testament to his remarkable and continued versatility. If Freedom explored the corruption and crime of an urban eventide, Sleeps With Angels gazes into the embers left at sunrise. Grim and bluesy tunes like "Safeway Cart" and "Trans Am" split the difference between JJ Cale and Dire Straits, while the sobering "Driveby" is a great example of Crazy Horse's rarely-heard lighter touch. Neil must have really liked the melody and arrangement of "Western Hero," as the song reappears on the album under the title "Train Of Love," with only a different set of lyrics to distinguish it. The 15-minute "Change Your Mind" overstays its welcome a bit, as do a cluster of songs in the third act that seem to slip by unnoticed, but much of Sleeps With Angels is latter-day Neil at his brooding best. File under: Dark Side Of The Harvest Moon.

Freedom/ Eldorado (1989)

The eighties were no harder on Neil than they were on any of his boomer peers; one might even argue that, in hindsight, his decade of failures paints a far less embarrassing picture. Sure, there was Landing On Water, but at least there was no Cloud 9 or Dirty Work. Nevertheless, Freedom, released in the final months of the decade, would constitute a rebirth. The decision to bookend the album with acoustic and electric versions of "Rockin' In The Free World," nodding to his last great album Rust Never Sleeps, is no more coincidental than Neil's sartorial appropriation of sixties Dylan on the front cover. Neil answers the bell, though, as the entirely of Freedom finds him renewed and in fine form. In addition to the enormous and widely acclaimed "Rockin' In The Free World," "Cocaine Eyes" points to the sludgy indulgences of Ragged Glory and Psychedelic Pill, while "Too Far Gone," written in the 70s and bootlegged ever since, is given a superb, Stones-y reading complete with mandolin. The real draw here, though, is the evocative "Crime In The City (Sixty To Zero)," whose episodic, half-empty vignettes recall some of Dylan's picaresque masterpieces. As comebacks go, Freedom is a knockout punch.

American Stars 'n Bars (1977)

Easily Neil's most underrated album, American Star 'n Bars is another in a long line of Neil Young 'identity crisis records,' but taken as a collection of songs, it's practically perfect. One of several albums to provide sanctuary for songs orphaned by the aborted Homegrown album (others ended up on Hawks & Doves and the retrospective Decade), American Stars 'n Bars contains a first side of mostly excellent country rock material and a particularly strong second: "Star Of Bethlehem" is an Emmylou Harris-assisted bit of folk rock confection that would have been right at home on Harvest; pot-paean "Homegrown" is silly but irresistible; and the dosed-sounding "Will To Love" is a heartfelt loner folk tune about, err, salmon. This leaves the fireworks display that is "Like A Hurricane," one of Neil Young & Crazy Horse's most potent guitar epics, on par with "Cortez The Killer," "Down By The River" and "Cowgirl In The Sand." Any Shakey disciple who doesn't own a copy of American Stars 'n Bars should have their fan club membership revoked at once.

Harvest Moon (1992)

1991 is the year punk allegedly 'broke,' as sarcastically suggested by the title of a 1993 film documenting Sonic Youth's European tour with Dinosaur Jr, Mudhoney, and Nirvana. Only a character as confident as Neil Young would show his appreciation for being honored by the stalwarts of the burgeoning alternative rock scene by releasing the most grown-up album of his career. The commercial sound of Harvest Moon risked potentially alienating his new grungie fans the way he'd been alienating boomers, hippies, and, well, everyone else, for years. Of course, it was not Neil's intention to vex his new street team with an accessible, middle-aged sounding record; the truth is decidedly more mundane: after decades of skull-rattling live performances, Neil was finally having hearing trouble. In my anniversary piece on the album last year, I describe Harvest Moon as the 'mellow, ethereal' antidote to the previous year's Ragged Glory. Though comparisons to Harvest are facile, Harvest Moon does share many of the laid back qualities of that classic album, but where the former is understated, even rudimentary, the latter is spectral and lush, and would provide a formula for several future Neil Young albums. And why not? Harvest Moon is a rarity: a platinum, top twenty, Grammy-nominated album that stands the test of time.

Time Fades Away (1973)

The oft-neglected third part of the so-called Ditch Trilogy that also comprises On The Beach and Tonight's The Night, Time Fades Away has been commercially unavailable for years: as of this publication, it is joined only by the Journey Through The Past soundtrack as the only Neil Young album not available on CD. This obscurity may explain, in part, its current status as ugly duckling. At first listen, Time Fades Away also appears sunnier, if only relatively so, than the tormented Tonight's The Night and the down-and-out On The Beach. The truth is far more complicated: for all of the talk of Tonight's the Night as Neil's booziest, bleakest LP (it is surely one of the booziest and bleakest ever made), it is the tequila-fueled Time Fades Away that captures Neil at his most blasted and punk-petulant. Performed and recorded entirely live to arena crowds unfamiliar with the new material and waiting to hear "Heart Of Gold" and "Only Love Can Break Your Heart," Time Fades Away is the sound of an increasingly estranged Neil actually going through the dark stuff he'd write about and perform later on Tonight's the Night. The album casts Neil as both the sadist and the masochist, baiting his faithful audience like some hostile punk rocker hocking gobs of mucus into the crowd, only to have the spurned, disapproving crowd spit back. As for the songs, they're great: "L.A." is a cutting ode to the seedy 'city in the smog' of its title; the homicidal-sounding title track throws the same sort of barrelhouse haymakers as "Tonight's the Night" or "Southern Man"; and the resplendent piano ballads "Journey Through The Past" and "The Bridge" are clinics in heartfelt, honest songwriting. Fans of On The Beach and Tonight's the Night who are unacquainted with Time Fades Away should consider tracking it down at any cost; I'm envious of anyone who gets to hear it for the first time.

Comes A Time (1978)

Comes A Time began as a solo album of plaintive, acoustic songs, but would soon morph into a grandiose to-do recalling the majesty — and expense — of Harvest following Neil's decision to augment the songs with overdubs by a host of A-listers (including Bobby Charles, Spooner Oldham, and JJ Cale) and, most crucially, the vocals of Nicolette Larson. Like the harmonies of Emmylou Harris and fiddle of Scarlet Rivera on Bob Dylan's Desire, Larson's voice is integral to the atmosphere of Comes A Time; no one, with the possible exception of Danny Whitten, has ever blended so beautifully and so naturally with Neil's reedy tenor. Two songs feature Crazy Horse, captured here on their best behavior: the narcotic "Look Out For My Love" and the confessional "Lotta Love." (Larson's version of the latter would soon earn her a top ten hit, and is perhaps the only Neil Young song bested by its cover version.) The magnificent, unashamedly commercial Comes A Time sounds born of experience; it's not an album one makes in his or her twenties. In this way, it again parallels its closest analogue, Desire: its wisdom is sophisticated, its comforts well earned.

Harvest (1972)

The canonized Harvest is the album that would earn Neil Young his only number one hit ("Heart Of Gold"), as well as the autonomy and beyond-reproach status he's enjoyed ever since. With the release of Harvest, Neil Young — by now already an unlikely minor celebrity — would find himself propelled to a level of fame and infamy he would spend years trying to claw his way away from. But that was later: In 1972 Neil was in love with actress Carrie Snodgrass, and was, for the moment, enjoying his newfound artistic and financial freedom. Assembling an ad hoc band he dubbed the Stray Gators, Neil created Harvest in fits and starts with a handful of producers and guest stars spread out over multiple sessions and locales. The album is funky and loose, with capacious production that allows each sound to imprint itself on even the most casual listener. It is a landmark album and a pivotal release. All of this is not to say it is Neil's greatest work. In fact, very few of the songs on Harvest rank alongside Neil's best. For all of its popular appeal, Harvest is uneven: for every brilliant "Old Man" there is an "Alabama"; for every "The Needle and the Damage Done," a "There's A World." Even the ubiquitous "Heart Of Gold" is, at best, merely a pretty good Neil Young song. Quibbling aside, the performances on Harvest are truly exemplary, and the sound of the record has perhaps as much to do with its enduring legacy as the songs contained therein.

Zuma (1975)

In many ways the quintessential mid-'70s hard rock album, Zuma is Neil's 'dude record.' Recorded in Malibu, of all places, and presided over by the great David Briggs, Zuma is an extremely direct, almost reverb-free affair with a great live feel. The album captures Neil and Crazy Horse in a jubilant mood following several years of personal lows that resulted, for better or worse, in some of the most emotional and brilliant music of Neil's career. Three songs on the previous year's devastating On The Beach featured the word "blues" in their titles, but on Zuma, there is just one, and despite its lyrics of nightmares and dying a thousand deaths, the ecstasy that runs through "Barstool Blues" is palpable. The good-time vibe of the album can at least partially be ascribed to Crazy Horse's newest member, the outrageous Frank "Poncho" Sampedro, who replaces the late Danny Whitten on guitar, and brings with him a devil-may-care optimism that would help counter some of Neil's dark tendencies for years to come. The album reconciles many of Neil's moods, spanning subtle acoustic fare ("Pardon My Heart" and "Through My Sails," featuring Neil's then-former bandmates Crosby, Stills and Nash), playful throwaways ("Drive Back," "Stupid Girl") and landlocked surf guitar downers ("Dangerbird"). Mostly, though, Zuma orbits around the impressionistic "Cortez The Killer," a guitar epic that effectively redefines psychedelia for an emerging generation that was, by now, in closer temporal proximity to video games than to bell-bottoms. For this song's inclusion alone, Zuma is a pinnacle.

Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere (1969)

Co-opting members of a small-time Laurel Canyon bar band called The Rockets and dubbing them Crazy Horse — no one remembers why — Neil seemed to have found his spiritual brothers in guitarist Danny Whitten, bassist Billy Talbot, and drummer Ralph Molina. Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere is the album they made together, and it is a record that oozes from its every groove a feeling of freedom and ancestral camaraderie. Talbot and Molina may have been rank amateurs, but together with Neil and Whitten, the band would define what jazz critic Gerit Graham once called 'skillful simplicity,' a machine greater than the sum of its parts creating singular music by way of alchemy. The members of Crazy Horse, however, would have to share the spotlight with Old Black, Neil's beloved 1953 Les Paul, also making its debut on Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere. Old Black, played through a Fender Deluxe tube amplifier at top volume, would hereafter become, like Crazy Horse, a most crucial weapon in the Neil Young arsenal. The serendipitous combination of Crazy Horse and Old Black would help to embolden Neil and allow him to musically communicate in ways in which he'd only dabbled before. During his tenure in Buffalo Springfield, he and Stephen Stills would frequently use the song "Bluebird" as a vehicle to engage in improvised, protracted guitar duels, but even these jams never approached the effusive lyricism found on masterpieces "Down By The River" and "Cowgirl in the Sand," featured here. Elsewhere, the title track and "Cinnamon Girl" benefit from Whitten's R&B and doo-wop background, which would lend Neil's songs a funkiness they'd previously lacked; this influence would haunt Neil's music for the rest of his career.

Rust Never Sleeps (1979)

The first Neil Young album to use the two sides of an LP to demarcate two disparate moods, Rust Never Sleeps features an acoustic side and an electric side, and was largely created by overdubbing instruments onto live recordings of performances from the tour preceding the album. Side 1 begins with an acoustic reading of "My My, Hey Hey," a declarative anthem of longevity which has ironically achieved notoriety for supplying Kurt Cobain with a well-publicized quote used in his suicide note: "It's better to burn out than fade away." Elsewhere, "Thrasher" is a vivid daydream that jabs at former associates; "Pocahontas" manages to cram Native American myth, the Astrodome, and Marlon Brando into the same improbable campfire hallucination; "Sedan Delivery" sounds like some glorious, five-minute long car crash; and the blockbuster "Powderfinger" is an exquisite narrative threaded together by some of the most expressive guitar playing of Neil's career. It ends with a snarling "Hey Hey, My My" (an electric reprise of opening cut "My My, Hey Hey"), and if you've ever wondered what sort of record Hendrix might have made if he lived long enough to experience punk, wonder no more. With Rust Never Sleeps, Neil Young ended the seventies with a great album; it would be over a decade before he would make another one.

After The Goldrush (1970)

Neil's third album is an album of and for its time. Despite its humble beginnings as a soundtrack to a Dean Stockwell film that was never made, After The Goldrush seems to capture Neil at the summit of his powers following the success of the Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young album Déjà Vu, released earlier that same year. Guitarist Danny Whitten's escalating drug problem was by now becoming problematic — this would be the last Neil Young album Whitten would play on before his death by overdose two years later — forcing Neil to augment Crazy Horse with an assortment of other musicians including Jack Nitzsche, Crosby, Stills and Nash, and child prodigy Nils Lofgren. The approach proved fruitful: After The Goldrush plays like a greatest hits package, containing classics like the Graham Nash-inspired "Only Love Can Break Your Heart," the sci-fi piano ballad "After The Goldrush," the pounding and accusatory "Southern Man," and the stoner-logical "Tell Me Why" among its many highlights. It's not merely one Neil Young's best albums, or even one of the finest albums ever made — it's Scripture.

Tonight's The Night (1975)

Tonight's The Night is part funeral, part séance. Rarely, in any medium, have abjection, misery and disillusionment manifested themselves so gloriously as catharsis, or resulted in greater art. Tonight's The Night finds our chapfallen hero reeling from the drug-related deaths of two friends: roadie Bruce Berry and Crazy Horse guitarist Danny Whitten. Within these tormented songs, Neil veraciously chronicles the void like a Fender Broadcaster-slinging Rimbuad in Elvis shades. The band members, out of tune and out of their heads, follow suit, underpinning the shit-faced atmosphere with bloodshot, feral accompaniment. Never has rock and roll exhibited such compassion or volunteered so much pain; never has a musical artist gambled so recklessly with their reputation in an attempt to express their innermost feelings at any cost. Tonight's The Night is less a record than it is an open wound. At its heart, the album is redemptive, but the path to that redemption would seem to require immolation; Tonight's the Night will leave ashes on your turntable. The songs — morose, disturbing, and magnificent — are, for once, beside the point.

On The Beach (1974)

List my ten 'desert island discs,' you ask? On The Beach, and nine backup copies of On The Beach. Neil's magnum opus was not masterminded by Neil or even David Briggs but by pedal steel guitarist Ben Keith, who assembled a once-in-a-lifetime backing band including, among others, Rick Danko and Levon Helm of The Band, bassist Tim Drummond, Crosby and Nash, and, most crucially, Cajun legend Rusty Kershaw. On The Beach is what people mean when they use the expression 'lightning in a bottle'; Neil would never make another record like it. The album is made up of rough, and not master, mixes, simply because Neil got familiar with the preliminary versions and grew to love them. Engineer Al Schmidt was livid, begging Neil to let him remix the hastily assembled album at his own expense, but Neil was having none of it: it was perfect the way it was. Though he only actually plays on two tracks, Kershaw's influence on the album cannot be overstated: A brother-from-another-mother type who exerted a great influence over Neil, encouraging his preference for capturing sublime moments over technically perfect takes, Kershaw also introduced the band to a homemade concoction called 'honeyslides,' a marijuana-and-honey cocktail that results in near-total catatonia. Whether you consider the second side of On The Beach an enticing advertisement for or a cautionary warning against honeyslides, the specter of this homegrown treat is undeniable. Neil, ever the method actor, was also smoking two packs of cigarettes a day to get his voice sounding appropriately 'late night.' Whatever Neil had to go through to create On The Beach, it was worth it, because this album has it all: Tremulous, maniacal jams about murder and ecoterrorism? Check. Heavy-lidded Appalachia? Got it. Comatose downer blues? Several of those. Excoriating social commentary? All over the place. Every moment contributes to make On The Beach an album that musically narrates the dimming of a day, or an epoch. Like Neil in the cover photo with his back to the camera, transfixed by the ocean amidst a shore full of detritus and ruins, it suggests not endings, but a Mobius strip of overlapping, unsteady beginnings; it's the sound of Neil cautiously gazing away from the wreckage, at last, and into the great wide open.