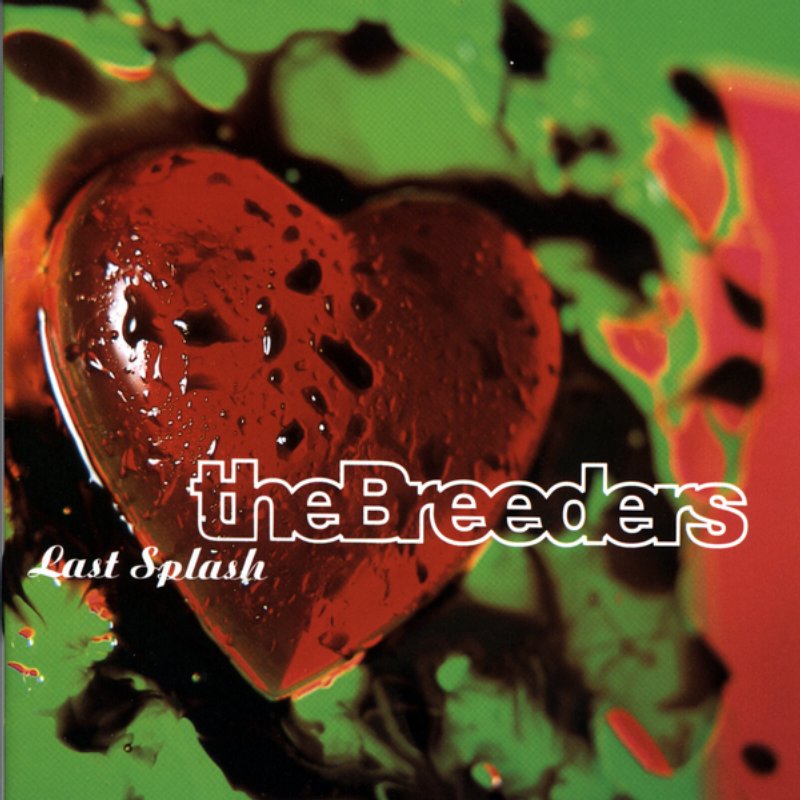

The Breeders' second album Last Splash was an indie rock album that became a hit. That means something else right now. An indie album that becomes a hit -- Bon Iver, Bon Iver, say -- dominates critics' list, racks up summer-festival bookings for the band, maybe wins a Grammy or two. A track might appear in a TV commercial. An open-eared rapper might freestyle over one of its songs. Solange will tweet about it. Last Splash was not that. Last Splash was a hit in the '90s sense -- a million copies sold in less than a year, heavy radio and afternoon-MTV rotation, a spot on the Lollapalooza mainstage before the Beastie Boys but after a Tribe Called Quest. Kim Deal appeared on the cover of Spin when you could sometimes find Spin next to the conveyor belt at the supermarket. And it was also an indie rock album in the '90s sense -- weird tunings, songs with no identifiable chorus, the same song repeated one and a half times just because, melodies that seemed to be fighting their way upstream just to escape from the guitar-tangles. One of the album's two guitarists had just learned the instrument the year before. The drummer had never seen drum monitors before the band opened for Nirvana in Europe. This was a warm, homemade, deeply and consciously odd lark of an album that came to rule summertime car stereos, and it is still baffling that this happened at all. Two decades later -- the album turns 20 on Saturday -- it's fun to look back and wonder about it.

Last Splash isn't the only leftfield success story of its era; a year later, Beck rode arguably even weirder music to even greater fame. But it's still a very telling story. The year before the album came out, Black Francis, the leader of Kim Deal's old band the Pixies, fired his entire band by fax. The Pixies had never had a hit, and now bands were starting to have hits by using variations on their sound. He wanted to go solo, and seeing as how he's never been shy about liking money, he probably hoped to hit some kind of solo stardom in the post-Nirvana wake. That didn't happen. He landed a song or two on the radio, but he was back to playing bars within a few years. His former bassist became a star instead, and she did it with a record that sounded nothing whatsoever like the Pixies. They're all rich now, thanks to that Pixies-reunion money, but that must've stung at the time. And maybe this stung, too: For my money, the Pixies never made an album as great as Last Splash.

Before she got fired from the Pixies, Kim Deal had gotten together with Tanya Donnelly from the Throwing Muses, as well as a couple of other people, and made an album of spidery amniotic dream-pop. Kurt Cobain loved Pod, but it had nothing to do with the kind of alt-rock that was getting big, or even marginally big. It was soft, woozy, complicated music, and you couldn't mosh to it. Donnelly left to form Belly, who got just as big as the Breeders, though they did it by making way-more-conventional guitar-pop music. (Really sorry I spaced on the Star-turns-20 piece, guys; that album rules.) And so Deal roped in Pod player Josephine Wiggs, Dayton bar-rock drummer Jim MacPherson, and her own twin sister, who, at the time, had no idea how to play guitar. (All this is in Spin's Last Splash oral history, which rules.) I can't imagine anyone expected much to come of the album. It follows its own logic, chasing its own tail all over the place. Songs riff on early-'60s surf rock, or Hawaiian tourist music, or Beatlesy flower-child psychedelia, or kids' lullabies. Near the end, out of nowhere there's an absolutely gorgeous old-school Grand Ole Opry weeper. The lyrics that jump out the most are oblique non-sequiturs that exist only to confuse -- "We were rich once before your head exploded," "Motherhood means mental freeze," "I don't like dirt." This isn't a straightforward rock album with a few weird asides. It's an album of nothing but weird asides, an album-as-weird-aside.

And yet the thing hangs together in ways that boggle expectation. The chemistry between the two Deal sisters is one of those uncanny alien things, those things where two twins say the exact same thing at the same time and you just shake your head and accept it because they're twins and twins are magic. When they sing together in close harmony, there's this shivery deadpan electricity, a sound that nobody else has captured or even attempted, in their voices. They can play fast, catchy, straight-up rock songs -- "Saints" is one of the best of its time -- but they're just as likely to break into a shambling proto-math-rock instrumental. And those tendencies -- which seem like they should conflict, but somehow don't -- are right there in "Cannonball," the single that made the band famous and catapulted them way beyond anything the Pixies achieved during their first lifetime. This is a weird song -- the distorted underwater ahooos in the intro, the bouncy falling-down bassline, the bursts of horrible feedback that work so hard to drown out the riff, the on-mic laughter, the nonsensical lyrics. And yet it's almost absurdly catchy, the type of song where, if you're 13 when it comes out, you get in trouble for trying to play the drum part on the back of the driver's seat on the way to school. It's a completely tossed-off garage-pop trifle that rightfully stands as one of the defining hits of alt-rock's boom period.

Confession time: I bought Last Splash at the time. Splurged for the CD, even, rather than just buying the five-bucks-cheaper cassette, which was what I usually did. And I thought I didn't like it. I loved "Cannonball." Loved "Saints." Really liked "I Just Wanna Get Along." The rest of it made no sense to me. I hated "No Aloha," thought it sounded like a dumb joke. Thought "Divine Hammer" sounded like some lame oldies-radio thing. Sneered at the canned strings and scratchy bursts of noise, totally had no patience for it. And yet, I must've listened to this fucker hundreds of times. Part of that was probably an attempt to justify the $15 expense, or to hear what the writers at Spin who loved it heard. But listening to it years later, the whole thing is second-nature, and I sure can't say that about, say, the Mutha's Day Out album that I also bought. (Although this is still stuck pretty deep in there.) I had the CD, not the tape, so I could've just skipped to the three songs I thought I liked, but I never did that. Played the whole thing through every time. And two decades later, listening to the album for the first time in forever, I know those first four snare-cracks on "Roi" like I know every freckle on my forearm.

There was no follow-up to Last Splash. The Breeders toured hard behind the album and then drifted apart. Kim Deal and MacPherson formed a new band called the Amps, made an album, got some radio airplay. Kelley Deal developed a really serious heroin habit, got arrested, subsisted through most of the late '90s on the royalties she got when the Prodigy sampled "Cannonball" on "Firestarter." In 2002, Kim and Kelly got together with, in typically improbable fashion, the rhythm section from some iteration of the terrifying early-'80s hardcore band Fear, and they recorded Title TK, the third Breeders album. I was in college then, and I got so excited. That's a good album and not a great one, but I bought it on the day it came out, then drove for an hour and got lost in southwestern D.C. so I could see them on that tour. (Made it into the Capitol Ballroom in time for "Cannonball," but not for "Saints," and I'm still pissed about that.)

I don't remember where I changed my tune on hating Last Splash; my tastes in music weren't even that different from what they'd been when it came out. But somewhere along the line, that album had sunk its way in, done its work, reshaped my brain in some small way, and I'd realized that I loved it. This year, the band got back together, in its Last Splash-lineup form, to play the album in full on tour, which probably means that a whole lot of people had gone through a process with the album not too dissimilar from mine. The reunited Last Splash Breeders got serious press, drew great reviews, got booked to festivals. If it had been, say, Belly touring Star, I doubt they would've been granted the same levels of nostalgia-love. But sometimes it's the stuff we resist the hardest that we end up loving the most. Or maybe great pop songs mean more to people, years later, when they take more left turns, or when they are left turns.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]