The first time I heard Nine Inch Nails, I was barely fourteen, hanging, unsupervised, with my friend at the time and his older brother — a "bad kid" judging by his pierced ear and Grateful Dead T-shirt. We sat on his dingy floor while he sparked a joint and asked us if we wanted to hear some quote-unquote real music, something to make us stop listening to The Eminem Show on repeat. He played what I later found out was the Broken EP. When I asked him what this music was he said, "What they play in the strip clubs in hell." There began a lifelong interest in Trent Reznor, mastermind and sole core member of Nine Inch Nails.

Of course there is more to Reznor's sound than sleaze, hard beats, and roaring guitar. The man has experimented with every genre of popular music from electronica to metal to jazz, but at his core, Reznor's strengths have always been hooks and lush production, things he inherited from his favorite bands as a teenager: KISS and David Bowie.

Reznor's also contracted some of those bands' weaknesses. For an acclaimed singer-songwriter (which he is, underneath the electronics and black cutoffs), Reznor has never been the greatest lyricist or singer. He's grown into the nasal croon that has defined his style, but it wouldn't work in any other band. His most-celebrated topics — drugs, kinky sex, paranoia, depression, sticking it to the man — make him the perfect rock star for a 14-year-old boy in a strange, dirty room filling with funny-smelling smoke, but not exactly the sort of person one expects to make profound statements about life, politics, and the nature of human existence (even though he has done so when the stars align).

Regardless of his flaws, with Grammys and an Oscar under his belt, recent collaborations with Lindsey Buckingham of Fleetwood Mac, and a discography of multi-platinum albums, Trent Reznor has graduated from reclusive addict-genius to the ranks of his childhood idols: bona fide pop music luminary. No other "extreme" musician besides Ozzy Osbourne has wormed his way so far into mainstream pop -- but unlike Ozzy, Trent Reznor is nobody's clown. He's become one of the most forward-thinking musicians and producers when it comes to using technology. Rockist luddites say that modern production techniques sap the soul out of music and make it lifeless, but even they embrace Trent Reznor. The core of his technique, the thing he does most brilliantly, is coax organic sounds out of computers.

Since the release of his latest album, Hesitation Marks, the man who once gave the cold shoulder to a Rolling Stone reporter is giving 45-minute lectures on his process and offering insider looks at his always spectacular live shows. Before his 2009 hiatus, Reznor was posting live clip after live clip from his would-be farewell tour with reckless abandon. Reznor hasn't just transformed from scrawny nobody into sex symbol, from junkie into clean liver, and from rocker into composer -- he's gone from being an introvert to an extrovert, inviting everyone interested to examine him and his work. It's the perfect time to bring his entire discography, with all of its successes, failures, and inconsistencies, into context. These are Trent Reznor's albums -- released under his own name, or with longtime co-pilot, Atticus Ross, with recent project How To Destroy Angels, and of course with Nine Inch Nails -- from worst to best. Reznor's discography is actually a bit larger than the one presented here, but I chose to focus on work where he took the steering wheel himself -- the Lost Highway and Natural Born Killers soundtracks were both mostly composition albums, and so were not included, even if each one boasts a worthy fan-favorite Nine Inch Nails song ("The Perfect Drug" and "Burn" respectively). Also Reznor's soundtrack to the original Quake videogame was excluded, firstly because it is no longer commercially available, and secondly because, come on, it's the soundtrack to Quake. All three would hover near the bottom of the list.

Not so much unsuccessful as unnecessary, the An Omen EP appeared in late 2012 less than six months before Welcome Oblivion, the first (and so far only) full-length How To Destroy Angels album. Too late to function as a stopgap, the EP more or less exists as promotional material for Welcome Oblivion, which also sports the lion's share of the EP's material. The two songs unique to the EP — "The Sleep Of Reason Produces Monsters," and "Speaking In Tongues" — are good, but overshadowed by other material. There are NIN singles and remix albums with much more interesting material than those two tracks put together.

This four-disc collection of experiments marked a major turning point in Reznor's career. Reznor's first independent release, Ghosts was released in part as a free download, in reaction to his stormy relationship with Interscope during the promotional period for Year Zero. Ghosts is unlike every other NIN release: a series of unnamed instrumental songs, varying wildly in tone and instrumentation, some completely electronic, others nearly acoustic. And while some of them are quite good, others come across as demo takes, sketches, or just plain unfinished ideas. Reznor intended some of that unfinished quality: He encouraged his fans to sample and remix Ghosts, even hosting some of his favorite pieces on NIN's official website. Reznor even took part in the re-mixing himself: Some bits of Ghosts later became songs on The Social Network and The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo soundtracks. Taken as a work unto itself, Ghosts bores most of the time, but it foreshadowed better work to come.

Released the same year as Ghosts, and just over a year after Year Zero, Reznor released The Slip in the middle of a blitz of creative fertility. The first few songs on the album have an almost garage-rock sound to them, while its back end slips into chilly ambience — more remnants from Ghosts, maybe. Where Year Zero was all about loops, The Slip is all about percussion, and its titanic drum sound is probably its best feature. The Slip explosively decompresses from excitement to boredom, but still sports its gems. "Discipline," the album's radio single, is a so-stiff-it's-funny disco track about Trent getting clean as well as his love of S&M. You can read it as a tongue-in-cheek re-imagining of "Closer," complete with a music video that sported an 8-bit NIN dressed as the Village People. On the other hand, the album's raucous closer, "Demon Seed," sounds like Reznor's take on boom-bap hip-hop, albeit with him crooning and growling instead of actually rapping.

Right off the top, The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo soundtrack opens with an incredibly memorable cover of Led Zeppelin's "Immigrant Song," featuring vocals by Karen O of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs. It's one of the only acceptable Led Zeppelin covers out there, one that probably drove sales of the record more than fan allegiance to the film or its franchise. And after that, the record grinds to a halt. All the detail and brooding that Reznor and collaborator Atticus Ross work into their compositions feel limp after such an introduction. The record finally picks up again at the end, when How To Destroy Angels cover Bryan Ferry's "Is Your Love Strong Enough?" another must-hear cover (seriously, Maandig kills it). Reznor has done better instrumental work elsewhere, and one can only assume he will produce better soundtracks in the future.

After Reznor's second hiatus from Nine Inch Nails, his sorry-for-the-wait album is electronic, percussive, and highly loop-driven. It's also relatively quiet and laid-back sounding — par for the 2013 course, after similarly relaxed albums by Nick Cave and David Bowie. For an album featuring contributions from guitar legends like Lindsey Buckingham of Fleetwood Mac and Adrian Belew of King Crimson (among many, many other bands), it's nearly guitar-less. The exception is the bizarre power-pop track "Everything," with its sugary mix of Foo Fighters, Sleigh Bells, and Torche; the song comes out of nowhere and has no place on the record. In many ways, the album feels like the spiritual successor to Year Zero, Reznor's "laptop" album. But while that album was largely ahead of its time, Hesitation Marks just sounds like Reznor jumping on the back of a pickup truck that's already carrying Radiohead, the Knife, and nearly every critically acclaimed electronic-indie record that's arisen since the beginning of his relative silence. In its favor, Hesitation Marks is eclectic, and its standout songs — "Came Back Haunted," "Satellite," and "In Two" — are worthy of the NIN legacy. Still Reznor has done better work with his wife, and their band How To Destroy Angels, of late.

For a husband-and-wife project, How To Destroy Angels produces lonesome music. Reznor's first full-length LP with his wife Mariqueen Maandig has an Antarctic outpost quality to it — the title track sounds like the last radio broadcast from a depopulated earth. For all that, it's a modest, occasionally upbeat affair, composed mostly of subtle orchestration and drum loops. "Ice Age" blends some acoustic instrumentation for a bit of flavor, while lead single "How Long?" turns Maandig into a hysteric siren with a wall of vocal overdubs, but otherwise Welcome Oblivion is content to simmer. Maandig has a better voice, classically speaking, than her husband, but spends most of her time in a gentle croon. The first full-length How To Destroy Angels LP, unlike the roar of Reznor's earlier work, sounds like an album of lullabies to sing listeners into a final, eternal rest.

In the years following Reznor's post-The Slip hiatus, he's shed many of the indicators of his style — angry vocal delivery, loud guitars — in favor of more subtle soundscapes. And some more of that rock instrumentation colors this record … just not very much of it. Whether middle age and married life have mellowed him out, or this has been a conscious shift, the How To Destroy Angels EP is the most classically Reznor-sounding album he's made since that vacation. Maandig's voice has a soulful timbre that her husband lacks, and she uses it to coat these six tracks with the same sleazy self-destruction that made his early albums so engaging. "BBB (Big Black Boots)," for example, takes the "every woman loves a fascist" sentiment of Sylvia Plath's poem "Daddy" and turns it on its ear to great effect. Later, "A Drowning," reaches back to the hopeless pleading of The Downward Spiral, but only momentarily.

That said, The Fragile has not aged well. Like most double-albums, it overstays its welcome. Worse, it ping-pongs from the melancholic apocalyptic imagery of its best tracks to some downright immature, would-be-singles. "Where Is Everybody?" and "No, You Don't" might have been better served as fan-favorite B-sides like "Burn" off The Downward Spiral. And single "Starfuckers, Inc." should have been left unmade entirely. The Fragile is beautiful, but deeply flawed — Reznor bested it with simplicity years later.

After a lengthy five-year period alternating between abuse and sobriety, deaths in the family, and a nasty case of writer's block, Reznor followed his most successful album, The Downward Spiral, with The Fragile, the most melodramatic and excessive piece of his career. In between records, Reznor contributed to the Natural Born Killers and Lost Highway soundtracks, and maybe as a result, The Fragile has a cinematic bent to it: Pieces from it have been culled by Hollywood to promote films such as Terminator: Salvation ("The Day The World Went Away"), Final Destination ("Into The Void") and 300 (album highlight "Just Like You Imagined"). More eclectic and progressive than any other Reznor album, The Fragile rockets from soft to loud, slow to fast, from funk to doom metal, sometimes combining all in one with jaw-dropping results, like "The Big Come Down." The album's finest moments are its instrumental passages and more epic, progressive suites such as "The Frail"/"The Wretched" and especially "La Mer"/"The Great Below," which segues from relaxing jazz into a firsthand account of a descent into hell. That song remains among Reznor's finest.

That said, The Fragile has not aged well. Like most double-albums, it overstays its welcome. Worse, it ping-pongs from the melancholic apocalyptic imagery of its best tracks to some downright immature, would-be-singles. "Where Is Everybody?" and "No, You Don't" might have been better served as fan-favorite B-sides like "Burn" off The Downward Spiral. And single "Starfuckers, Inc." should have been left unmade entirely. The Fragile is beautiful, but deeply flawed — Reznor bested it with simplicity years later.

That said, With Teeth is a dark horse with serious potential. Sobriety added some needed clarity and heft to Reznor's voice, allowing it to carry more tender songs like "Every Day Is Exactly The Same" and "Right Where It Belongs," as well as ragers "You Know What You Are?" and "Getting Smaller." It's Reznor's most rock-centric album since the Broken EP, and he bolstered that side of his music with a thick, beefy guitar tone, and some powerful drumming courtesy of Dave Grohl. There isn't one weak track on With Teeth, and some of them, like the bassy bolero that is "Sunspots," deserve greater critical revisitation. Lyrically, this is as clear and focused as Reznor gets, with most of his sexuality and apocalyptic imagery traded in for a direct dialogue about sobriety. But despite all the rock, it's the quiet moments — Reznor's tender crooning on opener "All The Love In The World," or the tambourine focus of the title track — that sell With Teeth as an unappreciated gem in Reznor's discography.

After a six-year hiatus, Reznor emerged from the studio a changed man. Sober, with a shaved head and absolutely ripped at age forty, he began the second phase of his career with a scaled-back album full of singles and ballads. With Teeth has its staple singles — "The Hand That Feeds" and consistently brilliant "Only" — but keeps away from the melodramatic highs of his earlier work. After the Apocalypse Now-level gauntlet that was The Fragile, With Teeth is conservative, minimalist and as close to easy-listening as Reznor gets, which may be why fan reaction to the record remains pretty cool.

That said, With Teeth is a dark horse with serious potential. Sobriety added some needed clarity and heft to Reznor's voice, allowing it to carry more tender songs like "Every Day Is Exactly The Same" and "Right Where It Belongs," as well as ragers "You Know What You Are?" and "Getting Smaller." It's Reznor's most rock-centric album since the Broken EP, and he bolstered that side of his music with a thick, beefy guitar tone, and some powerful drumming courtesy of Dave Grohl. There isn't one weak track on With Teeth, and some of them, like the bassy bolero that is "Sunspots," deserve greater critical revisitation. Lyrically, this is as clear and focused as Reznor gets, with most of his sexuality and apocalyptic imagery traded in for a direct dialogue about sobriety. But despite all the rock, it's the quiet moments — Reznor's tender crooning on opener "All The Love In The World," or the tambourine focus of the title track — that sell With Teeth as an unappreciated gem in Reznor's discography.

Unlike most soundtracks, however, The Social Network stands up well as an album by itself. Reznor took the ambient meanderings of the Ghosts experiments and hammered them into a cohesive listening experience. Many of the tracks blend together — that's sort of the point — but unlike many ambient records, Music For Airports, let's say, The Social Network packs definite highlights. "Hand Covers Bruise," with its aching waves of distortion represents the angst of young adulthood better than many pop songs. And Reznor's interpolation of Edvard Grieg's "Hall Of The Mountain King," is one of the most gripping and entertaining tracks he's put to tape.

Years from now, this suite of music will be remembered more fondly than the rest of Reznor's oeuvre by people who don't carry a torch for rock or pop music. The Social Network soundtrack catapulted him from 'just another rock star' to a composer of note when it won the Academy Award for best original score in 2010, and while it was not the first electronic score to do so — that honor goes to Vangelis's score for Chariots of Fire — it is the rare soundtrack that perfectly underscores its subject without drawing attention to itself. The Social Network soundtrack is elegiac and vaguely sinister, much like Jesse Eisenberg's portrayal of Mark Zuckerberg, and much like Reznor's persona for most of his career. It's the perfect synthesis of artist and subject.

Unlike most soundtracks, however, The Social Network stands up well as an album by itself. Reznor took the ambient meanderings of the Ghosts experiments and hammered them into a cohesive listening experience. Many of the tracks blend together — that's sort of the point — but unlike many ambient records, Music For Airports, let's say, The Social Network packs definite highlights. "Hand Covers Bruise," with its aching waves of distortion represents the angst of young adulthood better than many pop songs. And Reznor's interpolation of Edvard Grieg's "Hall Of The Mountain King," is one of the most gripping and entertaining tracks he's put to tape.

Year Zero is unique among Reznor's discography in terms of content, and that works in its favor. His second concept album, Year Zero brings the political vitriol that has always been a minor presence in Reznor's work ("Happiness In Slavery," "March Of The Pigs") to the fore. He does not sing about himself, rather he creates a science fictional future where the United States has become a surveillance state and a theocracy — not too far from the realm of possibility, then as now. All Reznor's vitriol and paranoia lend a sarcastic edge tracks like lead single "Survivalism." A few songs dabble in Reznor's tried-and-true obsessions with kinky sex and drugs, but both of those become fully integrated in his fictional milieu — "Meet Your Master" projects his BDSM obsession into an interrogation room.

Sonically, Year Zero did away with the rock instrumentation that Reznor had employed before, and experiments with electronica and hip-hop. The watchword here is minimalism: Reznor and Atticus Ross wrote most of the record on laptops during the With Teeth tour, and maybe some of that on-the-run energy bled into the music. It's the more well-formed predecessor to Hesitation Marks, in that regard. Reznor cited the Bomb Squad as an influence, and it shows in Year Zero's frequent transitions from noise to dance beats. He even invited emcee and performance poet Saul Williams to guest on two tracks and produce an excellent hip-hop remix of "Survivalism."

During its hour-plus running time, Year Zero dabbles in so many styles and sounds heretofore absent from Reznor's work that at times it barely holds itself together. "Capital G," gets funky, while "God Given" has Reznor spitting his very own rap verses (no, he's not the best, but at least he did it). The climactic dubstep breakdown in "The Great Destroyer" ranks as one of the most dramatic moments in his discography. Closer "Zero-Sum" wrenches the ghost from the machines in what becomes kind of a subdued gospel tune. Year Zero is Reznor at his host humble and most experimental — the last truly perfect record he's done with Nine Inch Nails.

Year Zero, the black sheep in Reznor's discography, is his most underrated album, and probably the strongest collection of songs he's churned out since his first hiatus. Although the record received generally positive reviews upon release, it's seldom discussed. There's a few reasons for this: Year Zero is probably better remembered for the in-depth alternate-reality game that accompanied its release, and Reznor's subsequent falling out with Interscope records, than for any of its songs. It was released relatively quickly after With Teeth, only produced two singles, and was then followed even more quickly by the free release of Ghosts 1, and then The Slip.

Year Zero is unique among Reznor's discography in terms of content, and that works in its favor. His second concept album, Year Zero brings the political vitriol that has always been a minor presence in Reznor's work ("Happiness In Slavery," "March Of The Pigs") to the fore. He does not sing about himself, rather he creates a science fictional future where the United States has become a surveillance state and a theocracy — not too far from the realm of possibility, then as now. All Reznor's vitriol and paranoia lend a sarcastic edge tracks like lead single "Survivalism." A few songs dabble in Reznor's tried-and-true obsessions with kinky sex and drugs, but both of those become fully integrated in his fictional milieu — "Meet Your Master" projects his BDSM obsession into an interrogation room.

Sonically, Year Zero did away with the rock instrumentation that Reznor had employed before, and experiments with electronica and hip-hop. The watchword here is minimalism: Reznor and Atticus Ross wrote most of the record on laptops during the With Teeth tour, and maybe some of that on-the-run energy bled into the music. It's the more well-formed predecessor to Hesitation Marks, in that regard. Reznor cited the Bomb Squad as an influence, and it shows in Year Zero's frequent transitions from noise to dance beats. He even invited emcee and performance poet Saul Williams to guest on two tracks and produce an excellent hip-hop remix of "Survivalism."

During its hour-plus running time, Year Zero dabbles in so many styles and sounds heretofore absent from Reznor's work that at times it barely holds itself together. "Capital G," gets funky, while "God Given" has Reznor spitting his very own rap verses (no, he's not the best, but at least he did it). The climactic dubstep breakdown in "The Great Destroyer" ranks as one of the most dramatic moments in his discography. Closer "Zero-Sum" wrenches the ghost from the machines in what becomes kind of a subdued gospel tune. Year Zero is Reznor at his host humble and most experimental — the last truly perfect record he's done with Nine Inch Nails.

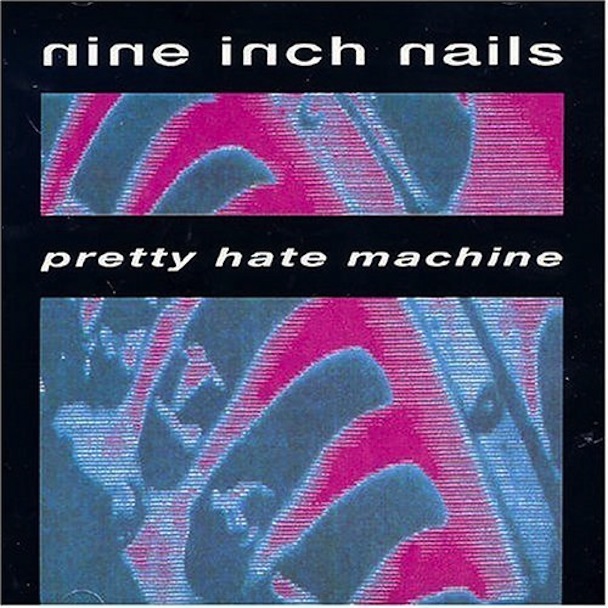

Trent Reznor cut his musical teeth playing keyboards with new-wave and synthpop bands Option 30, the Innocent, and the Exotic Birds — and it shows. Pretty Hate Machine's cocktail of buzzing processors, samples, and synth riffs isn't far removed from music by Depeche Mode or Soft Cell around that time. Performed almost exclusively by Reznor himself, the instrumentation on Pretty Hate Machine is a cut above most bands of the time: industrial and synthpop albums tend to get repetitive, but every song here has its own signature, like the slap bass hook on "Sanctified," and the processor stingers on "Sin."

What really set Pretty Hate Machine apart, though, was its attitude. Reznor sounds absolutely haggard here, crafting a combination antihero-everyman character, making himself a stand-in for every person who has ever felt betrayed. The lyrics read like a hit list, populated by Gordon Gecko types ("Head Like A Hole") treasonous femme fatales ("Sin") and God almighty on "Terrible Lie," from whom he demands "a great big apology." In 1989 synthpop was still reeling from the New Romantic image, but Reznor became its dark, creepy antithesis — one can practically see the knives sticking out of his back.

Pretty Hate Machine is not perfect — lyrics have always been Reznor's Achilles heel and some of the songs here, like "Kinda I Want To," and "Down In It" are downright embarrassing. Still, Pretty Hate Machine gets around the bases far more often than it strikes out, and even packs a few awesome but often-overlooked songs, like Reznor's first (excellent) ballad, "Something I Can Never Have," and the album's disenchanted closer, "Ringfinger."

Pretty Hate Machine is the kind of album legends are made of. The story goes: Trent Reznor, working as a custodian at a Cleveland recording studio, recorded the Pretty Hate Machine demo tracks on the sly, and later parlayed that demo into working around the world on the final record with renowned producers like Flood and John Fryer. The resulting LP was the first independently released album to go Platinum in the US. From janitor to jet-setting rock maverick before the album even dropped, it's the kind of outsider victory that high school dropouts foam at the mouth for. The fact that the album was out of print for eight years just added to its mystique. Somehow, Pretty Hate Machine eclipses its own origin story — it's one hell of a debut record.

Trent Reznor cut his musical teeth playing keyboards with new-wave and synthpop bands Option 30, the Innocent, and the Exotic Birds — and it shows. Pretty Hate Machine's cocktail of buzzing processors, samples, and synth riffs isn't far removed from music by Depeche Mode or Soft Cell around that time. Performed almost exclusively by Reznor himself, the instrumentation on Pretty Hate Machine is a cut above most bands of the time: industrial and synthpop albums tend to get repetitive, but every song here has its own signature, like the slap bass hook on "Sanctified," and the processor stingers on "Sin."

What really set Pretty Hate Machine apart, though, was its attitude. Reznor sounds absolutely haggard here, crafting a combination antihero-everyman character, making himself a stand-in for every person who has ever felt betrayed. The lyrics read like a hit list, populated by Gordon Gecko types ("Head Like A Hole") treasonous femme fatales ("Sin") and God almighty on "Terrible Lie," from whom he demands "a great big apology." In 1989 synthpop was still reeling from the New Romantic image, but Reznor became its dark, creepy antithesis — one can practically see the knives sticking out of his back.

Pretty Hate Machine is not perfect — lyrics have always been Reznor's Achilles heel and some of the songs here, like "Kinda I Want To," and "Down In It" are downright embarrassing. Still, Pretty Hate Machine gets around the bases far more often than it strikes out, and even packs a few awesome but often-overlooked songs, like Reznor's first (excellent) ballad, "Something I Can Never Have," and the album's disenchanted closer, "Ringfinger."

Reznor's songwriting on Broken is concise, and tighter than before — the four songs that comprise the album's core (those that are not instrumental interludes or covers) have each stood the test of time. "Last," with its merciless stomp, merges Reznor's sex drive with his more vitriolic songwriting to great effect. "Happiness In Slavery" veers from anthemic to confessional, one of Reznor's later specialties. "Gave Up" and "Wish," the two fastest, most metallic songs in Reznor's catalog, are so solid they've never left NIN's live set; according to Setlist.FM, he's played each more than both "Closer" and "Hurt." "Wish," in particular, has become so iconic that recording a cover of it is practically a heavy metal rite of passage. Reznor performed the song live with math-metal band the Dillinger Escape Plan, who have recorded maybe the best cover of "Wish," on NIN's last "farewell" tour.

Even the two covers are outstanding. His take on Adam Ant's "Physical (You're So)" burns slower, and hotter than the original — you can hear Reznor strain his vocal cords on the recording. The second cover, "Suck," was originally recorded by industrial metal band Pigface — really, just Reznor playing with the best live incarnation of 'the other' great industrial metal band, Ministry. Reznor's recording, with its "I feel so dirty on the inside" bridge, and overt display of sleaze, has become the definitive recording.

The Broken EP is the only true industrial metal release in Reznor's discography. It's also one of the best industrial (and/or metal) recordings ever put to tape. Pound for pound, it's as strong as The Downward Spiral, only less nuanced. It's just too short, and too one-note to be the central gem in Reznor's crown.

All of Reznor's (decreasing) credibility in the metal and industrial circles stems from this release, a six-song (eight, counting the two covers that comprise its bonus track), half-hour blast of noise. Perhaps inspired by Reznor's bitter feud with TVT, the label that released Pretty Hate Machine, Broken is as angry as Reznor gets — he does not sing, he screams. He offers no ballads, and shows no remorse. Unlike Pretty Hate Machine, Broken incorporates guitars into the Nine Inch Nails sound in a big way — they would not be so prominent again until With Teeth. Hilariously, one of the central instruments on Broken was a Mellotron originally owned by John Lennon — I wonder what that avid proponent of peace would think of his instrument supporting "the big time, hard line, bad luck, fistfuck." The hatred works in Reznor's favor; for the first (and maybe the last) time, Reznor's ridiculous lyrics actually work, adding to the record's blistering intensity. Listening to Broken on high volume is like watching magnesium burn.

Reznor's songwriting on Broken is concise, and tighter than before — the four songs that comprise the album's core (those that are not instrumental interludes or covers) have each stood the test of time. "Last," with its merciless stomp, merges Reznor's sex drive with his more vitriolic songwriting to great effect. "Happiness In Slavery" veers from anthemic to confessional, one of Reznor's later specialties. "Gave Up" and "Wish," the two fastest, most metallic songs in Reznor's catalog, are so solid they've never left NIN's live set; according to Setlist.FM, he's played each more than both "Closer" and "Hurt." "Wish," in particular, has become so iconic that recording a cover of it is practically a heavy metal rite of passage. Reznor performed the song live with math-metal band the Dillinger Escape Plan, who have recorded maybe the best cover of "Wish," on NIN's last "farewell" tour.

Even the two covers are outstanding. His take on Adam Ant's "Physical (You're So)" burns slower, and hotter than the original — you can hear Reznor strain his vocal cords on the recording. The second cover, "Suck," was originally recorded by industrial metal band Pigface — really, just Reznor playing with the best live incarnation of 'the other' great industrial metal band, Ministry. Reznor's recording, with its "I feel so dirty on the inside" bridge, and overt display of sleaze, has become the definitive recording.

The Broken EP is the only true industrial metal release in Reznor's discography. It's also one of the best industrial (and/or metal) recordings ever put to tape. Pound for pound, it's as strong as The Downward Spiral, only less nuanced. It's just too short, and too one-note to be the central gem in Reznor's crown.

Trent's first concept album, The Downward Spiral takes a man — presumably Reznor — and follows his descent into promiscuity, addiction, madness, and eventually suicide. There are other characters — a policeman, let us call him "Piggy," and a woman, let us call her "Reptile," (the plot is quite vague, and mostly window dressing besides) — but really the focus is Reznor's straight line to implosion. He is "Mr. Self Destruct" and the first thing the album presents is the sound of him being beaten.

The Downward Spiral's first half, following "Mr. Self Destruct," is a series of industrial rock singles, the most clear and sensible songs on the record, fusing the pop and dance styles of Pretty Hate Machine with the industrial metal of the Broken EP. "Piggy" rides on a plucky bassline, before "Heresy," the only weak track on the album, comes out guitars wailing and quoting Nietzsche. "March Of The Pigs" feels like a song from the Broken EP before Reznor cuts it with a jazzy piano interlude that becomes the song's main selling point.

After that it's "Closer," the song, with its accompanying kinky music video, that made Reznor a sex symbol. Almost twenty years later, it's still sexy. How many young men and women bought their first handcuffs after hearing it? The mind reels. For all of its transgressive animal-like-fucking, at its heart "Closer" is a disco track — its all-important hi-hat was programmed specifically by Flood.

The Downward Spiral turns from a dark pop-rock record into something more sinister and complex toward the end of "Ruiner," after its iconic guitar solo, my favorite moment on the album. After that, rock instruments fade, and choruses of buzzing synths, like a swarm of distant locusts — the recurring insects in the lyrics — take over. Songs bleed together, and moods shift. The fear of "I Do Not Want This," becomes the rage of "Big Man With A Gun," and the holiness of "A Warm Place," becomes the nihilistic hunger of "Eraser." The Downward Spiral is, at its heart, about layers, thematically and musically — the second side of the album piles on and removes loops of synths, processors, guitars and drums until traditional song structures buckle and warp. Which is what makes "Hurt" so jarring — that song has its electronic accouterments, but it's the most stripped-down and straightforward track on The Downward Spiral. On other records, the ballad at the end would be a gentle reprieve from the noise, but here it's a raw, exposed nerve. For a man known for doing everything himself, and often writing about himself, Reznor's tough to pin down as a person, but "Hurt" is a brief window right into the soul of the artist. It's the song in his discography that feels the most autobiographical, and it's the ideal note on which to end his best album.

The Downward Spiral is the sort of album that people can read and discuss like a novel. It comes out of speakers and headphones densely layered. One could realistically write an entire book about The Downward Spiral and its creation (the album was recorded in the house Sharon Tate was murdered in, for example). Like many classic works of literature, it's a tragedy — hard to believe it's been certified quadruple platinum, and spawned two hit singles that still receive regular radio play.

Trent's first concept album, The Downward Spiral takes a man — presumably Reznor — and follows his descent into promiscuity, addiction, madness, and eventually suicide. There are other characters — a policeman, let us call him "Piggy," and a woman, let us call her "Reptile," (the plot is quite vague, and mostly window dressing besides) — but really the focus is Reznor's straight line to implosion. He is "Mr. Self Destruct" and the first thing the album presents is the sound of him being beaten.

The Downward Spiral's first half, following "Mr. Self Destruct," is a series of industrial rock singles, the most clear and sensible songs on the record, fusing the pop and dance styles of Pretty Hate Machine with the industrial metal of the Broken EP. "Piggy" rides on a plucky bassline, before "Heresy," the only weak track on the album, comes out guitars wailing and quoting Nietzsche. "March Of The Pigs" feels like a song from the Broken EP before Reznor cuts it with a jazzy piano interlude that becomes the song's main selling point.

After that it's "Closer," the song, with its accompanying kinky music video, that made Reznor a sex symbol. Almost twenty years later, it's still sexy. How many young men and women bought their first handcuffs after hearing it? The mind reels. For all of its transgressive animal-like-fucking, at its heart "Closer" is a disco track — its all-important hi-hat was programmed specifically by Flood.

The Downward Spiral turns from a dark pop-rock record into something more sinister and complex toward the end of "Ruiner," after its iconic guitar solo, my favorite moment on the album. After that, rock instruments fade, and choruses of buzzing synths, like a swarm of distant locusts — the recurring insects in the lyrics — take over. Songs bleed together, and moods shift. The fear of "I Do Not Want This," becomes the rage of "Big Man With A Gun," and the holiness of "A Warm Place," becomes the nihilistic hunger of "Eraser." The Downward Spiral is, at its heart, about layers, thematically and musically — the second side of the album piles on and removes loops of synths, processors, guitars and drums until traditional song structures buckle and warp. Which is what makes "Hurt" so jarring — that song has its electronic accouterments, but it's the most stripped-down and straightforward track on The Downward Spiral. On other records, the ballad at the end would be a gentle reprieve from the noise, but here it's a raw, exposed nerve. For a man known for doing everything himself, and often writing about himself, Reznor's tough to pin down as a person, but "Hurt" is a brief window right into the soul of the artist. It's the song in his discography that feels the most autobiographical, and it's the ideal note on which to end his best album.