Though the current fad is to compartmentalize indie rock of the last decade as something quaint, narrow, and somewhat embarrassing, the Decemberists shouldn't have to worry about the fickle listening preferences of tastemakers. Even at the height of indie rock's move to the mainstream, the Decemberists were never cool. Their early LPs, 2002'sCastaways And Cutouts and 2003'sHer Majesty The Decemberists were rightfully met with sideways glances and furrowed eyebrows by the indie culture. Measured skepticism was used to examine their olde-tymey subject matter, their sing-song melodies, their Renaissance Faire-inspired arrangements, their plain-jane fashion sense, and songwriter Colin Meloy's penchant for SAT vocabulary. Fans of intellectual art rock were generally more captivated with the Books and Sufjan Stevens at the time, while the Rapture and Broken Social Scene seemed more in touch with the indie rock's forming ideas of a rock star. Even a band called the Unicorns were cooler than the Decemberists in 2003.

With such a left-field sensibility as performers, it's not surprising that the Decemberists almost crashed out of the gate. After self-recording the six-song 5 Songs EP in 2001, Meloy has referred to the Castaways And Cutouts sessions as attempt to stem the band's decreasing momentum, and the debut LP was completed to fulfill a promise to his acclaimed writer sister, Maile Meloy, and done so with the suspicion that they were recording just for the sake of recording.

So why and how are we talking about the Decemberists in 2013, as a band whose last album, 2011's The King Is Dead sold 94,000 copies in its first week? For starters, the band had champions; a few brave souls that forced their music into the line of sight. "You like Neutral Milk Hotel? Oh, then you'll love the Decemberists. It's like NMH but they tour."

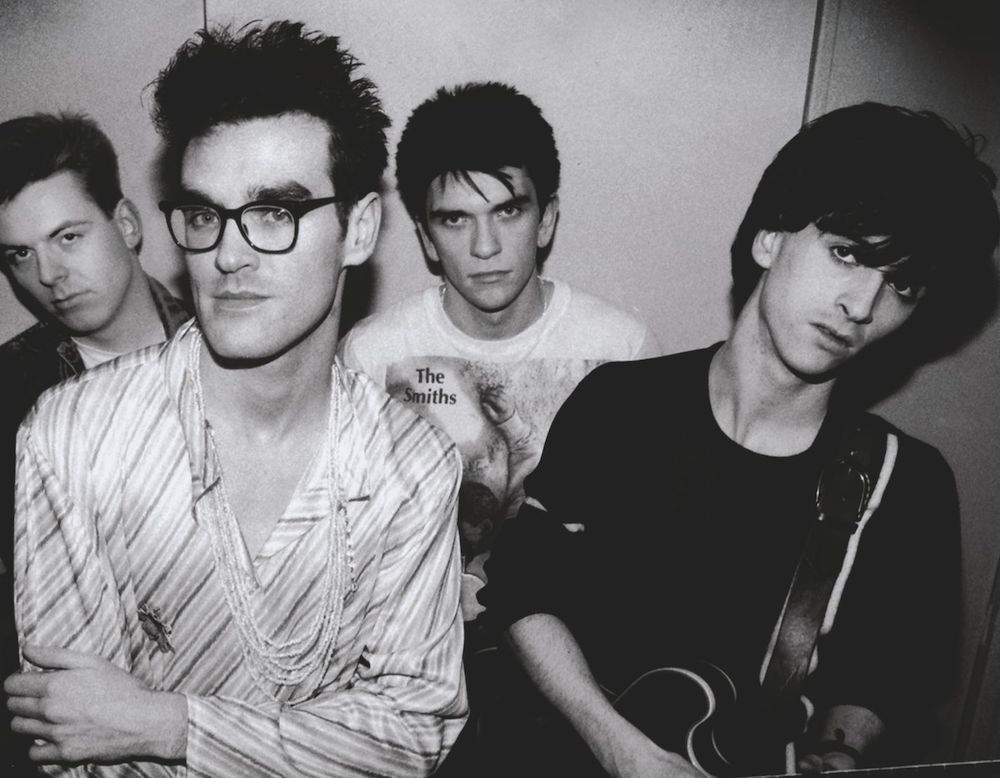

As the band progressed, other entry points could be found. Meloy covered Morrissey on a solo, tour-only EP. R.E.M. could be heard as an influence on "July July" and "Red Right Ankle" long before Peter Buck would join the sessions of The King Is Dead. Joanna Newsom's "Bridges And Balloons" would appear in the bonus offerings of Picaresque, an EP titled Picaresqueties. Meloy even wrote a 33 1/3 entry on The Replacements' Let It Be. Coming from the same musical background as the vocal indie fans of that era may not have got the Decemberists played at parties, but those who fell in love, fell in love hard. Further aiding their rise was the fact the meek, indie-leaning music writers could look at Meloy and believe he was one of them. A creative writing student-turned-musician, moving from the edge of the civilized world in Montana to the booming center of culture and art that is Portland (the dream of the '90s was alive, remember), Meloy's life was what a music journalist wished their own would be, and that made the Decemberists a band the blogs could root for.

But even the biggest supporters of the Decemberists seemed to perpetually be in the role of apologists, always taking the angle of convincing the hard-headed and stubborn hipster snobs. And even if 2005's Picaresque was the album to do just that, featuring production from Death Cab's Chris Walla and the band's most broadly appealing set of songs yet, the Decemberists promptly split from their indie, Kill Rock Stars, to join the majors, and became surprisingly proggy in the process.

Now, an antiquated sea shanty involving two men conversing from inside a whale is one thing, but prog? The Crane Wife welcomed what had been hinted at with their single-track EP The Tain and the band began talking openly about a love for Yes and Jethro Tull in The Crane Wife's promotion. The Decemberists proudly became Capitol Records employees, but nothing about their Capitol output speaks to a taming of ideas, a simplification or more accessibility. Instead, they went full-prog and recorded a rock opera, The Hazards Of Love, their most critically questioned work of their still dependable career.

This is the story of a band that had their first No. 1 album on their seventh full-length release, at the point that music culture seemed least interested in them and following their most misguided effort. And this is a story about what gets lost from a lot of the conversations about indie music in the early 2000s, and is true even now. Namely, that the culture breeds loyalty in a way that pop music just couldn't possibly. Pop music by its nature stays at a distance from its fans, while being a Decemberists fan could feel like real access to real people. Meloy joked about this in an interview, saying, "All the bands I loved growing up never made it past the like 800-capacity clubs. So, as far as I'm concerned I just would so rarely see bands like us -- and I don't even like us anymore. I used to -- I like our first couple of records."

The band has been on a bit of a hiatus following This King Is Dead, for both Colin Meloy wanting to spend time with his family and Jenny Conlee's recovery from breast cancer treatment. But Meloy has been writing new songs and is touring solo this fall in a tradition where he plays Decemberists songs by himself, sells a new covers EP at the venue, and uses the opportunity to try out his newest compositions. Before we hear those, let's look at the Decemberists' 10 best songs so far.

10. "The Wanting Comes In Waves/Repaid" (from The Hazards Of Love, 2009)

At least one of the Decemberists progressive stoner guitar jams is needed on this list, and the "The Wanting Comes In Wave/Repaid" is probably their best. And truth be told, it is a song better seen than just heard, as it begins buttoned-up and proper before reaching for an anthemic refrain that all seem like the point of the song. Then comes the riff rock. During the Decemberists touring of The Hazards Of Love, they brought along temporary Decemberists Becky Stark of Lavender Diamond and Shara Worden of My Brightest Diamond, both of whom recorded guest vocals for the collection. And on "Repaid" Wordon received the chance to sing lead and blow the minds the Decemberists' nightly audience, appearing as a barely five-foot ball of psychedelic boom-voice with high knee steps and an occasional karate chop. Props to a band for letting a guest steal the song, the album, and the tour.

9. "Apology Song" (from 5 Songs EP, 2001)

The sixth track on the 5 Songs EP is aptly titled, as Meloy penned "Apology Song" as a way to beg forgiveness for losing his friend's bicycle. Originally left on the answering machine of "Steven," the details in the narrative are relics of Meloy's past, with "Orange Street Food Farm" and "Frenchtown pond" familiar to few beyond the residents or visitors of Missoula, Montana. Unpredictable, though, must have been how fans would latch on to the spare detail of a "hesher," a term for a stoner-metal misfit. As a song, the mid-tempo acoustic throwaway resonates for its sweetness more than its humor, as Meloy calls the bike by a woman's name, "Madeline," turning "Apology Song" into a standard love song, and finding Meloy adept when working in familiar conventions.

8. "Red Right Ankle" (from Her Majesty The Decemberists 2003)

In a 2007 interview with the AV Club, Colin Meloy is asked why his songs drift toward obscure history, and why he doesn't just write songs about his girlfriend. Meloy responds that he does write songs both about and for his now-wife, Carson Ellis. Beyond being the inspiration for some key Decemberists songs, Ellis is also important to the band's story as the illustrator behind their album artwork. "Red Right Ankle" still, isn't a typical love song, and of course a "gypsy uncle" appears, as does a "hideout in the Pyrenees." But the last verse, after a lovely accordion breakdown courtesy of Jenny Conlee, that Meloy sings to the boys that loved Ellis, to those that broke her heart and to those whose heart she broke, is a moment of genuine inspiration for Meloy as a songwriter. It's a territory that love doesn't want us to explore, considering the past lovers of a current flame, but the maturity and compassion of Meloy in this verse is uncommon and quite beautiful.

7. "California One/Youth And Beauty Brigade" (from Castaways And Cutouts, 2002)

So, while the Decemberists were never cool, we sure tried to make them cool. A Pitchfork live report of a Colin Meloy solo performance -- which is impossible to imagine on the site in 2013 -- describes an audience that includes Sufjan Stevens, Lou Reed, and David Bowie. And Colin Meloy tries to make that crowd have a fucking singalong. The rendition of "California One/Youth And Beauty Brigade" that Meloy offers in solo sets is traditionally a highlight, with "Ask" from the Smiths tacked on to bring the song to a fitting conclusion. As untouchable as "Ask" is in the alternative canon, it doesn't upstage Meloy's originals, but rather gives context, puts Meloy in a tradition of misfit intellectuals, those too concerned with making a mark with something honest and real to be cool. And thankfully Meloy never tried to emulate his hero Morrissey. No one could ever be like Moz, and now, Meloy's stage persona is also his own, and something impossible to match or replicate.

6."The Crane Wife Part 1 & 2" (from The Crane Wife, 2006)

Really, throw "The Crane Wife Part 3" in and you have a contender for the top three, but as is, the first two movements of "The Crane Wife" serve as the climax of the album of the same name. Yes, the rubbery bass line comes close to biting "The Boy With The Arab Strap," but the first part of the song is a band growing brave, unafraid of expanding the scale of their music without drifting into proggy genre territory or relying on a gimmick. More importantly, the song provides a few minutes that you can legitimately dance to and not look like an asshole.

5. "Don't Carry It All" (from The King Is Dead, 2011)

Like "The Crane Wife 1," "Don't Carry It All" also bites another popular song, this one the beat and harmonica intro of Tom Petty's "You Don't Know How It Feels." But in kicking off the most recent full-length from the band, the tone of the collection is set. Gillian Welch can be heard singing backup. R.E.M.'s Peter Buck plays mandolin, a nod to the fact Meloy admits to channeling his R.E.M. love from his youth. When this song first came out, somebody commented on how Meloy's voice is especially mature-sounding on this track, and now it's all I notice, with his words keeping his center close to the ground, unshakable. The harmonies add to strength and evoke celebration, joy, and all the other natural byproducts that should be present in a song about gardening.

4. "The Mariner's Revenge Song" (from Picaresque, 2005)

Convincing someone of the greatness of "The Mariner's Revenge Song" takes the dedication of both parties, and probably involves the teacher demanding the student pay attention to the lyrics, until finally giving in and summing up the plot as the song progresses. And "plot" is not used lightly here, as it tracks a revenge story over many years as a boy seeks to avenge his mother's death, ultimately winding up face-to-face with his target in the stomach of a giant whale. The greatest sea shanty ever written? Probably, but "The Mariner's Revenge Song" has become so much more than that. The song's performance near the end of Decemberists sets is a ritual at this point, so much so that it was put on hiatus for a while from overplaying. One of their most self-indulgent moments, a song that shows a band to be capable, and even graceful in self-indulgence must be a classic.

3. "The Engine Driver" (from Picaresque, 2005)

The bummer in the creative-writing exercises that Decemberists songs can be, is that Meloy's use of characters completely foreign to the listener makes him difficult to get a sense of as an artist. If you've seen the self-deprecating humorist and charismatic performer that Meloy is, then you base your idea of him on that, but "The Engine Driver" might be one of the best songs in the Decemberists catalog to find Meloy hiding in plain site. The narrative gives brief flashes of seemingly unrelated characters -- the titular train operator, the electrical repairman, the banker -- all from who knows what time or place but all have reached the same point to be forced to say, "If you don't love me let me go." In the chorus, the song's actual central character is revealed to be the writer, creating stories to deal with his own romantic woes. Even without the surprisingly dense lyrical project, the way that Meloy changes up the way that he sings "trying to rid you from my bones" on the final chorus is as natural and comfortable as his voice can probably get.

2. "I Was Meant For The Stage" (from Her Majesty The Decemberists 2003)

When you write a song called "I Was Meant For The Stage," and you end up having a successful career, the song will surely come back to haunt you. It will be the cornerstone of profiles. It will be played off of for half-assed feature titles. It will be the running thread through your big cover story. The imagery of this string-laden ballad evokes the theater, and it is hard to believe that Meloy would be the speaker in the song, but seeing the Decemberists close with this cut at the Hollywood Bowl, backed by a full orchestra, was an emotional experience for all involved, and suddenly a little bit of the sappy sentiment that we'd all like to believe is true in ourselves is actually true in some. It certainly was for Meloy on that night. Of course, some people think the song is a suicide note -- and that just really makes it less enjoyable, so fuck that.

1. "On The Bus Mall" (from Picaresque, 2005)

Some of the best Decemberists songs are so ambitious, and successful in their ambition, that it's hard to explain why "On The Bus Mall" is the best song they have. It's six minutes long, but doesn't feel it. Its story is probably more foreign than the usual, unless you have lived the life of a runaway prostituting yourself to survive. And though it is full of minutia and spare jargon, the song stands apart from the rest of the Decemberists' work. Maybe it's the arrangement, with a fluttering guitar lead and twinkling accents that puts the band in a contemporary light for the first time. Maybe it's the unabashed emotion that pours out with each syllable Meloy lets loose. And maybe it is the universal aspects of the words. We've all felt love, maybe in the most unlikely of situations, maybe with someone we least suspect. We know the feeling "fusing like a family," of being "huddled close in the bus stop enclosure enfolding, our hands tightly holding." And maybe it is the one song that can stand alone without any idea of its meaning, lovely enough to exist as just a beautiful series of sounds. But Meloy's faith in language and ability to make listeners see themselves in characters from other countries and other centuries, all within the span of a few minutes, is the takeaway. He's got bigger things on his mind then being cool.

Listen to our Spotify playlist here.