If you were a music-dork kid in 1993, the kind who read music-magazine articles about albums that wouldn't come out for months, you were basically expecting Nirvana, one of the most popular bands in the world, to release a Wolf Eyes record. If you believed the magazines, which I absolutely did, then Kurt Cobain, so sick of the surprise fame that had been dropped into his lap two years earlier, was about to react to it by mangling ears everywhere, by making a record so sickening and abrasive that his own label was refusing to release it. There were all sorts of stories about mixdowns and single-choices and songwriting level, ideas that I didn't understand, but they basically amounted to this: Cobain was going to make damn god and sure that he'd never have to set foot in the MTV Beach House. He'd hired Steve Albini, a glowering and vaguely terrifying figure, to produce the album. (I really only knew of him because of PJ Harvey's Rid Of Me, which was the loudest and most damaging music I'd ever heard at that point.) He'd refused to let his label hear any of it. The business people were panicking. If this was all hype, then it was masterfully executed hype, since In Utero ended up as the first album I ever bought on its release date.

History has shown that it wasn't hype; there was real tension among the band and its handlers and Albini about the album, which ended up going through a few different mixes and which had a few different people's fingerprints on it by the end. Still, I can't imagine there was ever a point when DGC was going to scrap the album. Nirvana wasn't U2 levels of big in 1993, and even Pearl Jam had come to eclipse their popularity, but their world-shattering stardom was a very real thing. Nevermind had come out of nowhere, captured the popular imagination, and resulted in an unprecedented major-label signing spree. For a while there, it felt like every time Cobain mentioned a favorite band's name in an interview -- something he did often -- that same band would get a major-label contract a week later, regardless of marketability. The Melvins had a major deal. So did Unsane. So did Flipper, whose frontman had died five years earlier. It was nuts. Nirvana was a big deal; their songs were inescapable, their public stunts were the stuff of immediate legend (the Novoselic VMA bass-toss!), and bad approximations of Cobain's haircut ruined a few million yearbook photos. The idea of a Nevermind follow-up was a high-pressure situation commercially. And the pressure was even higher artistically, since Cobain was the type who felt that he had to encapsulate the entire scene that birthed him, to stay true to underground ideals that barely exist anymore, now that he suddenly had this huge platform.

Amazingly, he succeeded. In Utero was, and is, one hell of a rock record, and I'd say I like it more than either of Nirvana's other two studio albums. Albini's production job maybe wasn't the noise apocalypse that the press had led me to expect, but it was raw and thrilling. Its fuzz-roars and feedback-peals sounded wild and unencumbered without being self-consciously alienating. And even though Albini didn't like the mixing job, it's exactly what the album needed. Dave Grohl, a truly thunderous drummer, has never sounded heavier than he did on this album -- the "Scentless Apprentice" intro alone, my god. Cobain's voice was so strained and scraped and powerful, the sort of thing that would've worked amazingly in any context. And Albini had the right idea by recording them all in a room together and using minimal overdubs; it allowed them to sound like an actual band, like an old-school Cream-style power-trio. Even the most punishing tracks have their hooks, and whoever sequenced the album (Cobain, I guess?) had a perfect grasp of dynamics, dropping quietly shattering songs like "Dumb" among all the fuzz-bombs. The album spawned hit singles and sold a shitload of copies, so it did its thing commercially. And it brought the whole Midwestern/Northwestern scream-rock aesthetic to kids' ears pretty much unvarnished, doing nearly as much to tweak listening habits as Nevermind had. Within a few months of its release, I was riding my bike to the record store so I could spend my lawn-mowing money on Amphetamine Reptile compilations. That probably wouldn't have happened without In Utero.

Years later, In Utero is still held up as the iconic example of the audience-alienating "one for me" album, the one where a musician goes fully insular in the face of looming (or, in Cobain's case, already-existing) pop stardom. In Cobain's reported record-label battles, the album became, more or less, my generation's Apocalypse Now, with Albini's snowy Minnesota recording studio serving the same middle-of-nowhere function as Coppola's Philippines jungle set. And if you want to imagine In Utero as an album about unhappy fame, there's plenty of evidence there. The album's opening line -- "Teenage angst has paid off well / Now I'm bored and old" -- is one for the ages. Another famous one, on the album's catchiest song, almost matches it for sneer-factor: "I wish I was like you / Easily amused." The slightly-tweaked "Smells Like Teen Spirit" riff on "Rape Me" is an obvious provocation, as is that song's title. There's a song called "Radio Friendly Unit Shifter," and the song's tone makes it clear that the title describes a bad thing.

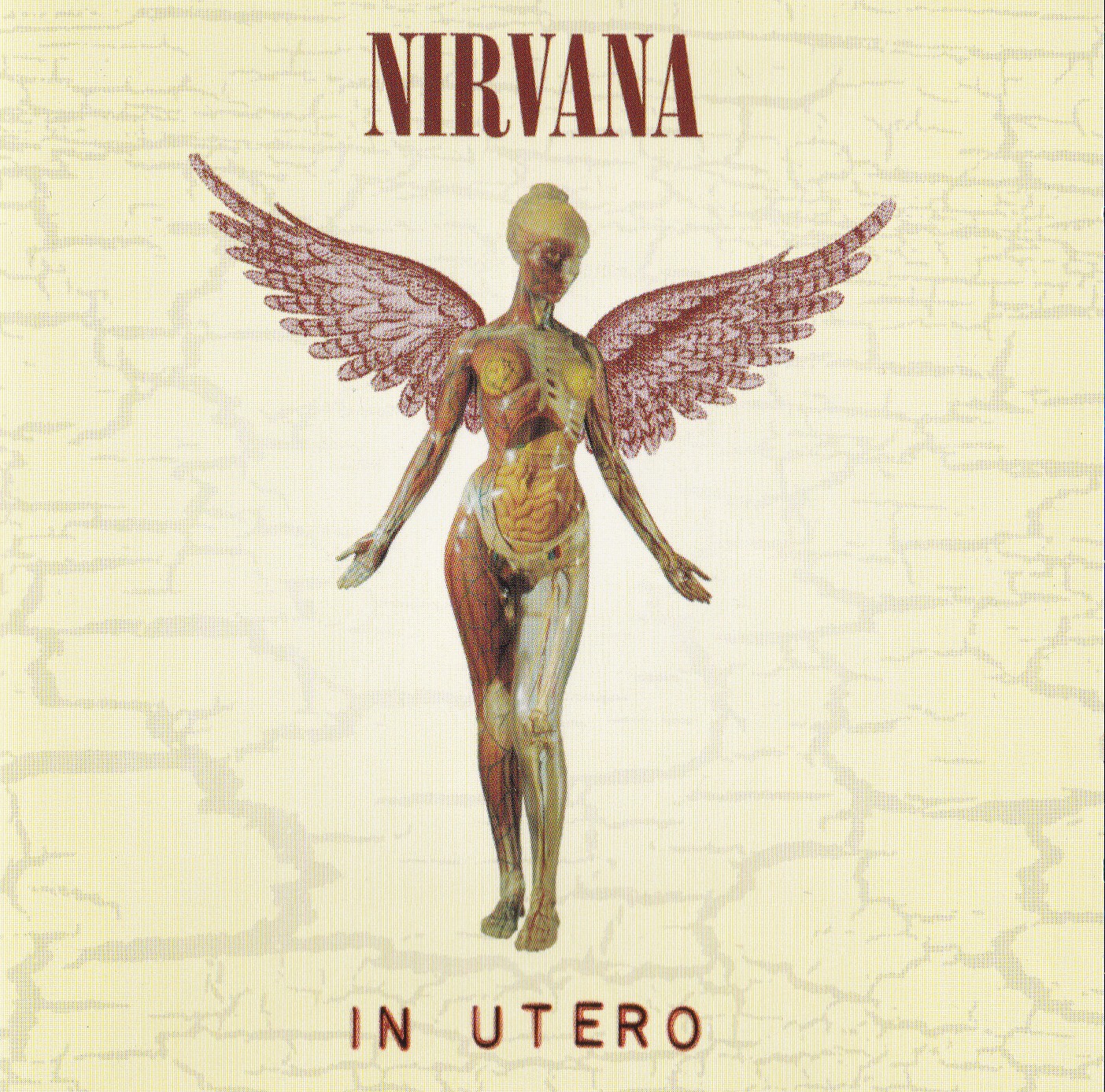

But listening to it today, having lived a little, In Utero now strikes a different chord with me. It's a tense, freaked-out new-fatherhood record -- you know, like Yeezus. The album's Wal-Mart-censored art was all anatomical fetus-based imagery. "Pennyroyal Tea" was named after a Victorian-era homemade abortion cocktail. There's a line about Cobain's own father -- "I tried hard to have a father, but instead I had a dad" -- that directly reflects the whole holy shit my upbringing was terrible thought-pattern that occurs to almost every new father. There are references to babies and childhood all over the place. Cobain once said in an interview that this stuff was all a coincidence, that they didn't have anything to do with his own new fatherhood. And as a 14-year-old, I was perfectly happy to accept these words at face value. Now, it's like: Come on. Obviously this shit was dominating his thoughts, the same way it dominates the thoughts of everyone who has kids.

And Cobain was certainly smart enough to know he wasn't about to be a great father. For one thing, he was a famous man with a famous wife, and famous peoples' kids don't exactly have a sterling record of health. And when he looked in the mirror, he saw a drug addict with crippling stomach issues, someone who owned a bunch of guns and harbored suicidal feelings, someone who was married to a crazy person. It's one thing to have a kid and wonder if you can hold your shit together. It's quite another to have your kid and know full well that you absolutely cannot hold your shit together, no way. That's what I hear when I hear In Utero now: Someone coming into the clear and indisputable realization that he was in way over his head, and that it was going to have disastrous consequences for himself and for everyone who he loved. Way more than the production choices or the passive-aggressive fame-talk, that's what animates this album: The primal terror of the shitty self-doomed father. That makes me love the album more, but it kind of makes me hate it, too.

In the comments section, go ahead and offer your own take on In Utero. What, if anything, did the album mean to you at the time? If you were old enough to be thinking about this kind of thing, how did it meet your expectations after Nevermind? How has it held up to you? How has its meaning changed? What memories do you associate with it? Do you listen to it more or less than Bleach and Nevermind?

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]