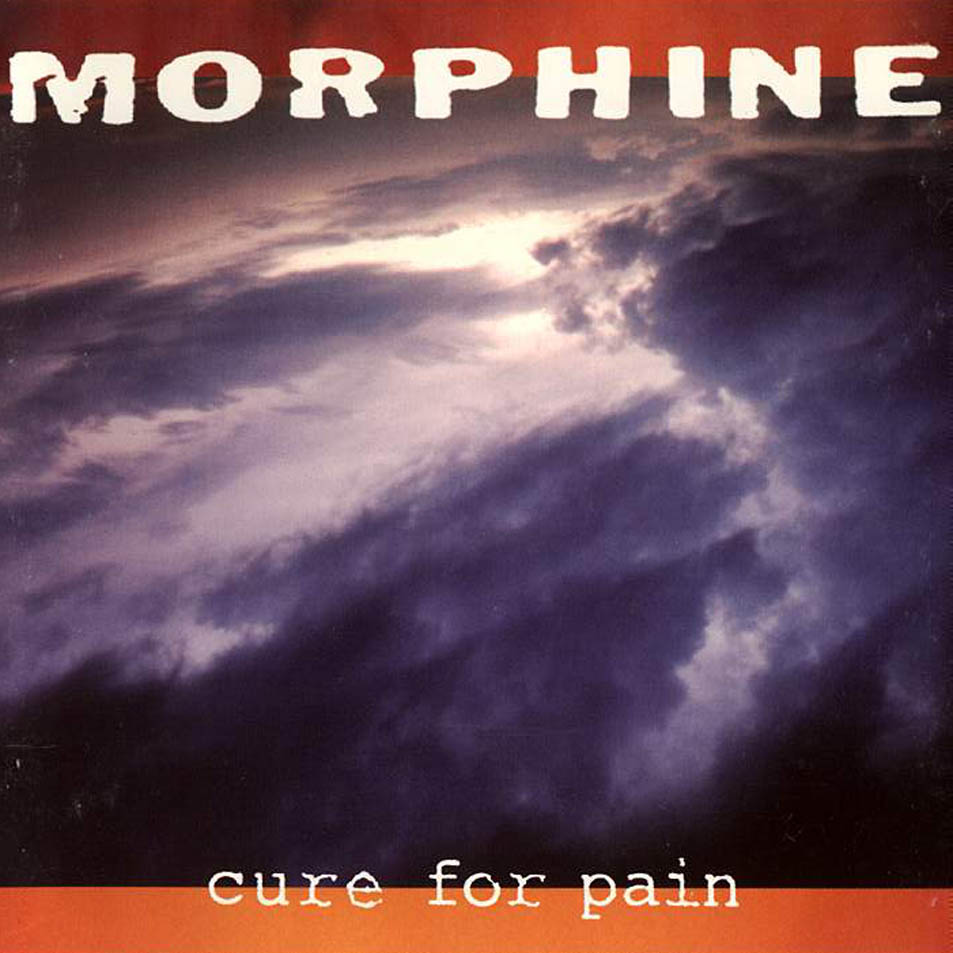

On September 14, 1994, two rock trios -- both marketed as alternative, both featuring sad and doomed frontmen -- would release really great albums, albums that would linger long after their moment had passed, albums that played important roles in indie/mainstream transitions. One of those albums was In Utero, and you already know about that one: Kurt Cobain's great and final wail of pressure and addiction and fame-alienation and new-father anxiety. Months after its release, he'd be dead by his own hand. The other was Cure For Pain, the second album by the Boston band Morphine. Cure For Pain was a lower-stakes album from a lower-stakes band -- a bunch of scene lifers who'd somehow stumbled into a breakthrough by making a low-end boho rumble that sounded really great in the backgrounds of movie scenes. But plenty of the themes on Cure For Pain, the ideas of drugs and longing and things being just out of reach, would sound familiar to Cobain. Morphine frontman Mark Sandman would live another six years after Cure For Pain, making a few more albums before dropping dead onstage in Italy after suffering a mid-set heart attack. If Coachella-style American festival had existed in 1993, Nirvana would've headlined, of course, and Morphine would've played on some mid-afternoon side-stage, in that Walkmen role of elegantly rumpled handsome underrated men. You don't hear too much about Morphine or Cure For Pain anymore, but it deserves its own look back, too. Let's give it its due.

Like a lot of other great bands, Morphine had a gimmick. In Morphine's case, they were the band with the weird instrumentation: No guitars, just drums and baritone sax and Sandman's two-string bass. Those instruments, combined with Sandman's slippery husk of a voice, meant that Morphine were entirely and completely made-up of low end. Their songs sounded low-down and sinister and slithery, and Sandman was happy to play up that side of things. The '90s were a great time for retro-greasers (Jon Spencer, the Rev. Horton Heat, various Tarantino and Tarantino-ripoff characters), and Sandman, who came off like a pool-hall townie beatnik, fit into the periphery of that whole thing. This was also a time where the idea of jazz -- as opposed to actual jazz -- had a certain cache, and Morphine letting loose with sax freakouts and naming and instrumental "Miles Davis' Funeral" slid in somewhere next to the Digable Planets' "Rebirth Of Slick (Cool Like Dat)" in the lineage of things that convinced middle-schoolers that maybe they liked jazz, at least until they tried listening to their parents' Spyro Gyra records.

But I hope I'm not underselling Morphine too much when I point out the various factors that went into them having a moment. If you've never heard the band, the previous two paragraphs probably read like the most dubious thing ever. But Morphine were a great rock band, great makers of riffs and hooks. Sandman's bass and Dana Colley's saxophone on "Buena," the song that got the most alt-rock radio burn in the day, were power-trio instruments, and the song's churn stuck to your gut. On "Let's Take A Trip Together," they were all forbidding-seductive throb, tossing off stoner come-ons with scary levels of swagger. Even on the simplest songs -- like "Thursday," where Sandman has to leave town to flee the husband of the woman he's been fucking -- pound and squawk so hard that the country-blues setup came off like something raw and vital, a lived-in narrative rather than an inherited cliche.

Sandman was already well into middle-age by the time he and his band made Cure For Pain, and he'd been through some things: two dead brothers, a stabbing sustained when someone tried to rob the cab he was driving. In his voice, there was a world-wearing authority that sounded terribly sophisticated and badass to the young teenage me. On the title track, where he wearily croons that he'll throw his drugs away the day they find a cure for pain, Sandman sounds lost but resigned, ready to slide into oblivion where someone like Cobain always sounded like he was fighting not to drown. On "Sheila," he makes some truly goofy lyrics about a girl and her cat sound stark and suave and lascivious -- an full-grown man reading high-school locker-room poetry and giving it everything he's got. The song that sticks with me the most is the bittersweet relationship lament where the sax and drums take a breather and Sandman whispers sad affirmations over nothing more than a mandolin: "I always knew you would succeed no matter what you tried / And I know you did it all in spite of me." There are a lot of emotions at work in that sentiment: Regret and resignation and displaced pride and scraped-out emptiness -- and you can hear them all at work in his voice.

Before he made Flirting With Disaster and Three Kings and I Heart Huckabees and The Fighter and Silver Linings Playbook, David O. Russell made his big splash with a movie with the '90s-as-fuck title Spanking The Monkey, and indie-drama Sundance darling in which Jeremy Davies fucks his mom. That was the movie's big news peg: It's called Spanking The Monkey, and it's about a guy who fucks his mom. As far as attention-grabbing stunts go, that goes beyond the cinematic equivalent of having a sax player and no guitarist. But if you could make it beyond that conceit (and the big spoiler of that conceit), you saw a tangled and fucked-up and sad and funny and powerful little movie, the sort of alive and vital thing that a festival like Sundance exists to honor. Russell would become one of the great transitional '90s indie-film figures: A talented and cantankerous fuck who pushed his work into weird places, pissed off studios, nearly got into fistfights with George Clooney, and somehow came out the other end as the sort of filmmaker whose movies routinely get nominated for Oscars. (Among this past year's Best Director nominees, I hold that he's the only one who's never made a bad movie.) You couldn't, in a million years, have foreseen Russell's career trajectory just by watching Spanking The Monkey, but all the talent was obviously there from jump. And for this subtly manipulative movie, a movie that gently leads its audience into considering the unthinkable, Russell picked just exactly the right music. Songs from Cure For Pain show up over and over in Spanking The Monkey. And in the movie's final scene, an emotionally cathartic and ultimately hopeful image that you feel like you've earned when you see it, the song that's playing is "In Spite Of Me." Maybe that's not quite the same thing as gatecrashing the mainstream and changing the course of rock history, but it's something.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]