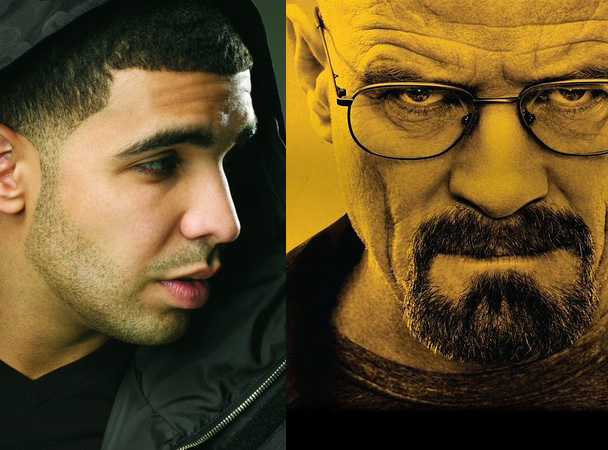

As far as I know, Drake has never murdered anyone (although, "you never know"). And contrary to that outdated yet stubbornly resilient rapper stereotype, he's never been involved with selling drugs. But as I was undertaking the absurd and Herculean task of ranking the rapper's 100 best songs earlier this week, I kept noticing how much Drake's attitude resembled that of Walter White, Breaking Bad's most antiheroic of antiheroes -- and that was before I was even aware of the viral Tumblr Drake-ing Bad, in which the great Houston rap journalist Shea Serrano paints Drake into scenes from the show. (Still decided to call this essay Drake-ing Bad because like Aubrey Graham and Walter White, I am stubborn.) I made the connection explicit in my writeup for "I'm On One," which concluded like so: "in Drake's world — much like his fellow egotist Walter White's world — there’s no such thing as happy endings for ruthless conquerors."

The more I thought about it, the more I realized these guys are kindred spirits, all the way down to being fictional characters of a sort if you buy Jeremy Larson's argument that Drake's emotional expression is a performance. They're two of a kind, and considering this week marks the release of Drake's Nothing Was The Same and the series finale of Breaking Bad, we might as well count the ways. (WARNING: Breaking Bad spoilers ahead.)

Both men seemed like harmless wimps at first but gradually revealed their inner monsters. People still crack jokes about how soft Drake is. The hilarious rap blogger/Ghostface Killah parody Big GhostFASE has made a cottage industry of it; his Take Care review is internet canon, and if you haven't read his Nothing Was The Same review yet, you're missing out, nah mean? But as Drake has grown more and more powerful and encountered more and more conflict, the cruel, merciless aggressor who was in there all along has come to the surface -- call it the "Tough Drake" era if you're feeling favorable toward him; proclaim "the mansion doors swing shut behind you and he mostly stops pretending to be nice" if not. A similar rise to power and the struggle to maintain that power turned mild-mannered chemistry teacher Walter White into a murderous drug kingpin. (Unlike Aubrey and Walter, we're merciful around here, so we'll spare you that oft-repeated maxim about Walt's transformation.)

Both alienate friends and family while claiming everything they do is for friends and family. Drake likes to talk about how everything he does is for his people; think "All I care about is money and the city that I'm from" or "There's times when I might blow like 50K on a vacation for all my soldiers just to see the looks on all their faces." But he frequently ends up shitting all over those same people when they rub him the wrong way. "Too Much" is the latest example of Drake using his records to put people on blast. On Fallon, he offered a disclaimer that he only wants what's best for his loved ones, but I can't imagine his mother enjoyed having a national TV audience hear that she's "cooped up in her apartment, telling herself that she's too sick to get dressed up and go do shit." Nor could any of his friends and family been pleased to hear Drake bragging that he achieved success all by himself on "All Me" -- not the mother who sacrificed so much for him, not the uncle who let him borrow his Lexus back in the day, not the producers and cast of DeGrassi, not mentors Birdman and Lil Wayne, not signature producers Noah "40" Shebib and Boi-1da, etc. etc. etc. Months after celebrating about "the whole team" being on top with him, he slapped the whole team in the face. As for Mr. White, he always insisted that his quest to become top dog in the meth game was to provide for his family before cancer took him out of the picture, but his actions directly resulted in his brother-in-law being euthanized Old Yeller style, his wife facing prison time and his son shouting "Why won't you just die already?" while refusing those barrels full of blood money, rendering all the soul-crushing bloodshed, sweat and tears for nothing once and for all.

Both are emotional manipulators. Walter White has a long track record of toying with the emotions of his supposed friends and family in order to get what he wants, particularly his partner and protege Jesse Pinkman. By tapping into Jesse's need for a father figure's approval, he's managed to convince the poor kid to do everything from breaking up with his girlfriend to getting deep in the meth business to murdering a hapless twerp. He's made marionettes out of his actual family too, nudging his wife into a criminal enterprise and making a fool of his teenage son. As with most of these categories, Drake hasn't sunken to the same extreme depths, but his catalog is littered with passive-aggression, mostly toward women who've spurned him; you can't wring your hands over all the good women settling down with somebody else (see: "Good Ones Go (Interlude)," "From Time") when you insist on sleeping around (see: the 2 Chainz collabs "No Lie" and "All Me"). But that's exactly what he does on "Marvins Room." The sad-sack rapper connives to convince a woman to take him back, shit-talking her current boyfriend while casually mentioning all the other women he's been banging.

Both present themselves as an array of different characters depending on who's watching. As referenced above, Drake is an actor at heart. He first made his name playing a character on a teen soap, and he's the definitive rapper of the carefully constructed social media era. That background shines through in his music, in which he takes on countless guises depending on the occasion. For evidence of his chameleonic tendencies, look no further than the first two singles from Nothing Was The Same; the ice-cold paranoia of "Started From The Bottom" and the warm goop of "Hold On, We're Going Home" couldn't be farther apart. Those are the two basic archetypes; you could boil it down to playing to the men vs. playing to the ladies, but it's deeper and more nuanced than that. His career is one big carefully orchestrated Facebook profile with gregarious talk-show appearances and mean-mugging rap-beefs shaping his public persona alongside the same way you or I would purposefully construct our lists of favorite bands and TV shows. Breaking Bad's main character has two primary modes too -- suburban dweeb Walter White and the vicious gangster Heisenberg -- and he's been known to toggle between them depending on whether he's trying to convince present company that he wouldn't hurt a fly or that he is the one who knocks. Walter White himself is a fictionalized construct, of course, but some of Bryan Cranston's best scenes on the show are Walt's performances within a performance, like that awful video confession he used to back Hank and Marie into a corner.

Neither one can let go of a grudge. Walter's lingering resentment toward his wife, his employer and his former business partners is what launched his entire drug escapade in the first place, and judging from last week's "Charlie Rose ex machina," it's also the catalyst that will bring the whole thing to a close. Drake is controlled by his grudges too. On songs like "Shot For Me," Drake airs grievances against ex-girlfriends who have no way to respond, while tracks like "The Motion" showcase his bitterness toward rappers who he believes have wronged him.

Both reveal the emptiness of the success fantasy, although both are too blinded by their egos to realize that. Drake famously rapped about his desire to be successful, then spent the majority of his career spouting lyrics like "Having a hard time adjusting to fame" and "What am I afraid of? This is supposed to be what dreams are made of." No matter how much he (rightfully) gloats about being rap's current king, he doesn't seem to enjoy it at all. Walt at least seemed to have fun during his brief tenure at the top, but he was in denial about the consequences of his actions, his heart 99 percent hardened because of it.

Most importantly, both are driven by their maniacal pride. Underneath all these parallels is the motivation for such monstrous behavior: a smoldering wounded ego of burning-star-core propotions. Drake can't stand the thought of being viewed as someone whose powerful friends and privilege were behind his success; Walt's ego can't allow him to let Hank go on thinking that sniveling Gale was Heisenberg. At the bottom of their blackened hearts, these men desire not only absolute power but unanimous recognition of their absolute power. They want to be known as royal geniuses, and it makes them royal pricks.