It's a bit of a challenge to write an anniversary appreciation for Heartwork. Anniversaries often imply that the best is behind (whether it's a band's catalog, a relationship or a sports franchise). There's an unstated assumption that what comes after will never surpass what has come before. Last month, Carcass proved that's not the case with Surgical Steel, one of the year's best metal albums, a record that stands alongside Heartwork in a career full of benchmarks. What's more, bandmates Bill Steer and Jeff Walker told us recently that they aren't close to being finished – hinting that there's a good chance they'll try to come back and top themselves and the expectations once again.

At the same time, it's impossible to discount the importance of Heartwork not just in Carcass's history but in the history of metal. The year 1993 was a watershed moment for death metal. It might not have produced as many canonical works as 1991 (Autopsy's Mental Funeral and Death's Human, for starters). But it's the year where bands flirted with risk – and major labels – and worked to make death metal more musical than ever. The year saw the release of Morbid Angel's Covenant (on Giant Records) which some consider the greatest death metal album ever; Pestilence's Spheres, an album that puzzled the shit out of fans with jazz and progressive elements; Atheist's Elements; and Entombed's Wolverine Blues. Some of these bands paid the price or took a long slumber before the metal public became more open minded. In the early '90s, death metal and risk weren't bunkmates: not toeing the line often meant exile in a scene where orthodoxy reigned.

Carcass's metal bonafides were unquestioned with their early grind classics Reek Of Putrefaction and Symphonies Of Sickness. Despite their extremity they were a known commodity in their native England thanks to interest from Jon Peel and the BBC, who also introduced Napalm Death to the general public. Like Covenant, Heartwork was released via a major label (Columbia via Earache). Labels were trying to find the next marketable thing after hair metal mercifully died off, and this time, they ended up with a band with an early song called "Genital Grinder." Carcass, nonetheless, had continued to change and evolve; Heartwork was without a doubt the most ambitious and risky move of all: an album that combined extremity and rock, a further riddle for fans who never moved past their earliest albums and a leap in songwriting and guitar work.

Heartwork is Carcass's most listenable album (at least until Surgical Steel). While their third album Necroticism: Descanting The Insalubrious might have signaled the beginning of melodic death metal Heartwork is where Carcass gave melodic death metal legitimacy. Carcass made death metal an art form, tested the limits of a genre known for inflexibility, forced it to come with cookie monster grunts into the future. Carcass is perhaps the first band that made death metal inherently, compulsively listenable from the go -- opener "Buried Dreams" grabs you as much as an old-school Judas Priest rocker.

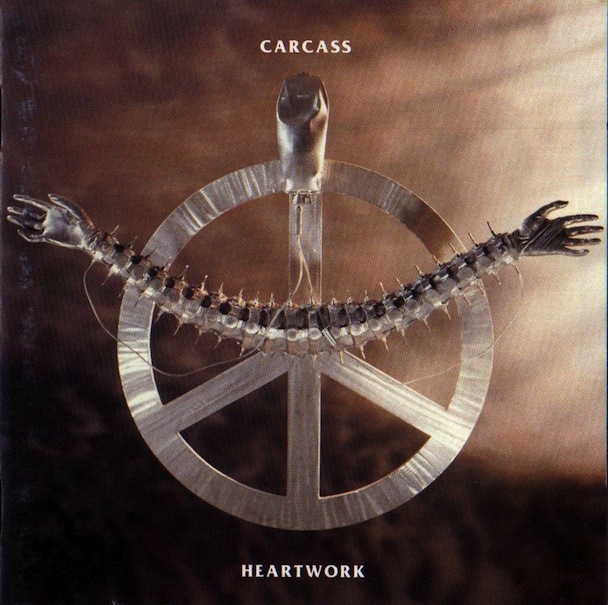

For many fans, Heartwork was their introduction to Carcass. The opening four songs are some of the best in the Carcass catalog: the catchiness of "Buried Dreams," the hook of "No Love Lost," and the rapid-fire riffing of the title track, echoed in "Captive Bolt Pistol" from Surgical Steel. Lead lyricist Walker had largely moved away from the medical references frequent on the first three albums to even more clever wordplay like "A canvas to paint, to degenerate/ Dark reflections -- degeneration," which rolls off the tongue. The art ("Life Support") was also a departure from earlier Carcass. It was a '70s original by surrealist H.R. Giger, who provided the iconic artwork for Celtic Frost's To Mega Therion in addition to creating the alien for the Alien franchise. Guitarist Michael Amott, who helped the band change course on Necroticism, returned for Heartwork before deciding to move on. Amott did not return for Surgical Steel, and it was up to Walker and Steer to reanimate Carcass well into the 21st century.

Heartwork was never a breakthrough. As Steer recounts in a Decibel Magazine Hall Of Fame feature on the album, the praise only came in later years. "As flattering as it is that people cite it as influential, at the time it was the wrong record entirely. If you look at the climate, it wasn't what the metalheads wanted to hear … What we're talking about is an underground band who is able to play in certain parts of the world. Could we actually make the next step up to a higher position? Well, we wanted to, but the reality was we just weren't able to." Heartwork, nonetheless, continued to find listeners. The album is a landmark, a patchwork of precise brush strokes giving new life to a music known for blunt force, proof that listeners can find beauty and complexity -- and compulsively listenable songs -- in a genre known for dissonance.

Carcass's earliest works like Reek continue to live on with legions of listeners and grindgore bands like Impaled and General Surgery. The afterlife of Heartwork is more lasting; you can hear it in every death metal band that worked melody into mayhem. It's evident in scores of records sold by Arch Enemy, founded by former guitarist Amott . It's even evident in old school stalwarts like Deicide, who enlisted Ralph Santolla to give their music a melodic touch on The Stench Of Redemption. Heartwork encouraged listeners to dig for inscrutable feelings and tough truths, to accept the seemingly bitter pill that sometimes extreme music should sound amazing. It's the moment when Carcass changed the sound of death metal.