It's easy to forget that the Smashing Pumpkins were outsiders. Not in the sense that many bands are — the weird, artsy, pained kids who find an outlet by playing loud rock music. The Smashing Pumpkins were outsiders from a wave of outsiders, often regarded by a sneer from their contemporaries as '90s alternative took over the mainstream. Because in writing about the past we need to make generalizations and group the survivors together, it's not uncommon to see Smashing Pumpkins' name in the same sentence as all the grunge bands, even as Steve Albini publicly denounced them and many were put off by what they deemed a blatantly careerist band. Of course, all these bands were getting huge and selling millions of records, but the key was to tell everyone very loudly how much you didn't want it. The Smashing Pumpkins, on the other hand, were rock stars in a traditional sense, just speaking in the more angst-ridden lingua france of Gen X. In a sense that, in hindsight, makes them one of the last of their breed.

Part of this is because the Smashing Pumpkins always seemed to have their feet splayed in different worlds. While most of the '90s alt rock bands held some debt to classic rock — and now often get grouped with classic rock, actually — Billy Corgan worshipped artists like ELO and Queen as much as he did Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath. This went beyond unhip; this signaled that the Smashing Pumpkins would have a greater deal of comfort with the idea of performance. Compared to all the grunge bands' aesthetics — the not-caring-about-your-appearance thing, which is really a very conscious decision in and of itself, but anyway —the Smashing Pumpkins looked prefabricated. Corgan was seen as an old-school rockstar egomaniac once tales of his perfectionism cropped up. If he'd re-record all his bandmates' parts, the rest of it could be artifice, too. He could've carefully orchestrated the band's diversity. And, throughout, he was always interested in the band's look, cultivating a kind of goth-glam mix through the mid and late-'90s, at times almost playing rock star characters. This was far more akin to what U2 was doing in the '90s than what Soundgarden or Pearl Jam were.

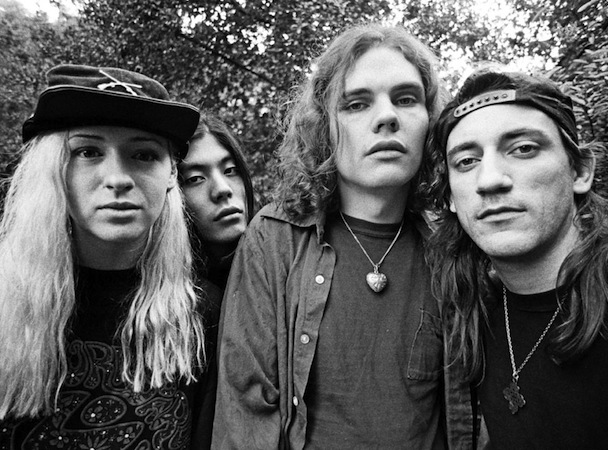

To a certain extent, the Smashing Pumpkins were indeed just something Corgan constructed. After a failed stint in St. Petersburg, Florida trying to find success with his first band the Marked, Corgan moved back to Chicago and plotted his next move while working in a record store. He already had the band name figured out when he met guitarist James Iha in that same record store. They met bassist D'arcy Wretzky at a show, arguing over the band they'd all just seen. In hindsight, it seems too perfect, the classic rock band origin story. Corgan hatched his band and then met people in the most expected ways, only needing the mythic entrance of a distinct drummer to make things fall into place. Jimmy Chamberlin was the final member to join, and his muscular style convinced Corgan to pursue a more aggressive direction musically. All of this is circumstance, how any band finds their way together. But there's something about the Smashing Pumpkins that seemed a perfect, unreal depiction of what a rock band was supposed to be in a time where the other major artists bristled against it. Maybe this is largely the media's doing, but the band came off as the intentional experiment of a sole architect passing himself off as bandleader, the most inauthentic of rock band concepts in a time that prized so-called authenticity.

And for a constructed rock band, a constructed rock band dissolution. Was there ever a totally good, peaceful phase in the Smashing Pumpkins' career? There was the big issue -- an alternative band at odds with the alternative world -- and there were all the smaller, personal strife issues. Just during their first tour alone, Iha and Wretzky's relationship fell apart, Chamberlin began nursing the drug habit that'd later get him kicked out of the band, and Corgan began struggling with depression. Once the Smashing Pumpkins became everything a rock band could imaginably be by releasing a sprawling double-album as their third record, just four years in, there wasn't really anywhere for them to go but down a slow path of disintegration. They'd deconstruct their sound, and they'd deconstruct the perfectly synced vision of a rock band they'd projected. There wasn't any big, dramatic flameout. After a few years spent alienating fans, Corgan announced preemptively that the band would release one more album and then quit.

He still had control over what would occur, but the narrative had wriggled out of his hands. Does anyone really talk about those last few years of the first incarnation of the Smashing Pumpkins? The main thing anyone seems to think of with the Smashing Pumpkins is those first three albums, and maybe Pisces Iscariot, exclusively. Which makes sense, on one hand, as it was undoubtedly their peak, and it's the music of theirs that you could most easily identify as being influential on recent indie artists. But it hardly gets at the expanse of their catalog, the sheer amount of music Corgan wrote and the weirdness of how the band released it. This makes for some unconventional territory for a list of this sort. Pisces Iscariot is a collection of b-sides, but it's a crucial entry in their catalog; the transitional phase of Teargarden By Kaleidyscope was left unfinished, but still seems important to note; MACHINA II was released for free on the internet in 2000, an album with a much lower profile and no official commercial release, but is one that many fans hold in high regard. For those reasons, these releases were included, while the smattering of other EPs and the expanded singles collection The Aeroplane Flies High were not. If there's someone out there who thinks Zeitgeist was a stunning comeback and the greatest thing since nu-metal, make your case in the comments.

Corgan claimed the shoegaze-y electronica of his first (and, thus far, only) solo outing TheFutureEmbrace was intended to stand independent of his past with the Smashing Pumpkins. If that was really his intention, he wound up short-circuiting it with his full-page ads in The Chicago Tribune and The Chicago Sun-Times the day of its release, June 21, 2005. The ads were ostensibly about his new album and his roots in Chicago, but Corgan totally buried the lede : there, in a few lines towards the end of the letter, he announced he was suddenly getting the Smashing Pumpkins back together. Of course, there were the mixed reactions when only Jimmy Chamberlin came back to the fold, some claiming it wasn't fully the Smashing Pumpkins without Wretzky or Iha. Others pointed out that Corgan had always been the architect of the Smashing Pumpkins anyway, Chamberlin his primary musical and personal foil, and that it was this duo that had been largely responsible for Siamese Dream — so, give the reunion a shot.

Well, it turns out the triumphant return was... less than spectacular. Released in 2007, Zeitgeist was the first Smashing Pumpkins album in seven years, and reeked of a mislead and somewhat callous attempt to recapture the band's heaviest elements. The most memorable distinction of Zeitgeist — even though it doesn't quite describe all the music therein — was that it's the most metallic of any Pumpkins record. Where before Corgan's metal interests had been shot through with glam or prog or shoegaze, here the rock songs seemed intent on attaining the most snarling, thrashing stance, but really just sound brittle, as uninterested as they are uninteresting. Dully aggro riffs lurch all over this thing, sounding more like a bunch of post-grunge castoffs than the urgent and emotive guitar parts Corgan had written for the Smashing Pumpkins in the past. The nadir is the interminable, tuneless "United States," plopped right in the middle of things, a yawning black hole at the heart of the record that suggests Zeitgeist might be even more cynical than it is disengaged.

It wasn't all terrible. "Bleeding the Orchid" fell in line with this heavier half, but has a melody I don't mind remembering. Even though he'd gone at least the better part of a decade without writing this kind of material, though, the rest of the rock songs sound pretty uninspired, and the more intriguing moments on Zeitgeist are those that depart from it entirely, such as the vibe-lead "Neverlost" or the New Wave melody that opens "For God And Country." Floaty closer "Pomp and Circumstance" is only OK, but it still seems a bright clearing in the clouds compared to the ponderous slog of much of Zeitgeist. Now that we know of the better things that would come after it, it could be easy to write off Zeitgeist as a bland misfire, maybe a bit of throat-clearing as Corgan got back into Pumpkins mode. However, with his occasional belligerence towards fans who rejected this material in favor of early classics and his continuing annoyance at being expected to play his older, most beloved material live, Corgan's petulance worsens the sting of how disappointing a return Zeitgeist was, making it easily the most severe musical blemish on the Smashing Pumpkins' history.

Corgan claimed the shoegaze-y electronica of his first (and, thus far, only) solo outing TheFutureEmbrace was intended to stand independent of his past with the Smashing Pumpkins. If that was really his intention, he wound up short-circuiting it with his full-page ads in The Chicago Tribune and The Chicago Sun-Times the day of its release, June 21, 2005. The ads were ostensibly about his new album and his roots in Chicago, but Corgan totally buried the lede : there, in a few lines towards the end of the letter, he announced he was suddenly getting the Smashing Pumpkins back together. Of course, there were the mixed reactions when only Jimmy Chamberlin came back to the fold, some claiming it wasn't fully the Smashing Pumpkins without Wretzky or Iha. Others pointed out that Corgan had always been the architect of the Smashing Pumpkins anyway, Chamberlin his primary musical and personal foil, and that it was this duo that had been largely responsible for Siamese Dream — so, give the reunion a shot.

Well, it turns out the triumphant return was... less than spectacular. Released in 2007, Zeitgeist was the first Smashing Pumpkins album in seven years, and reeked of a mislead and somewhat callous attempt to recapture the band's heaviest elements. The most memorable distinction of Zeitgeist — even though it doesn't quite describe all the music therein — was that it's the most metallic of any Pumpkins record. Where before Corgan's metal interests had been shot through with glam or prog or shoegaze, here the rock songs seemed intent on attaining the most snarling, thrashing stance, but really just sound brittle, as uninterested as they are uninteresting. Dully aggro riffs lurch all over this thing, sounding more like a bunch of post-grunge castoffs than the urgent and emotive guitar parts Corgan had written for the Smashing Pumpkins in the past. The nadir is the interminable, tuneless "United States," plopped right in the middle of things, a yawning black hole at the heart of the record that suggests Zeitgeist might be even more cynical than it is disengaged.

It wasn't all terrible. "Bleeding the Orchid" fell in line with this heavier half, but has a melody I don't mind remembering. Even though he'd gone at least the better part of a decade without writing this kind of material, though, the rest of the rock songs sound pretty uninspired, and the more intriguing moments on Zeitgeist are those that depart from it entirely, such as the vibe-lead "Neverlost" or the New Wave melody that opens "For God And Country." Floaty closer "Pomp and Circumstance" is only OK, but it still seems a bright clearing in the clouds compared to the ponderous slog of much of Zeitgeist. Now that we know of the better things that would come after it, it could be easy to write off Zeitgeist as a bland misfire, maybe a bit of throat-clearing as Corgan got back into Pumpkins mode. However, with his occasional belligerence towards fans who rejected this material in favor of early classics and his continuing annoyance at being expected to play his older, most beloved material live, Corgan's petulance worsens the sting of how disappointing a return Zeitgeist was, making it easily the most severe musical blemish on the Smashing Pumpkins' history.

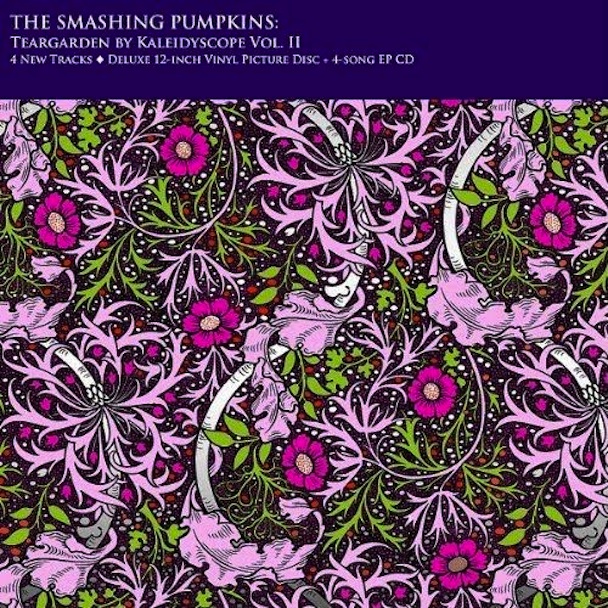

After Chamberlin's departure (or, possibly, dismissal) from the reformed Smashing Pumpkins, Corgan envisioned a path forward with an ambitious new recording project. Expressing dissatisfaction with the practice of releasing traditional physical albums on the traditional cycle and dealing with industry mores, Corgan planned to work on one song at a time, crafting each one specifically and releasing them as they were done, eventually leading up to a 44 track project at its completion made up of 11 4-song EPs and possibly a one disc distillation of the best material. This was half respectable, half suspicious — sounding partially rooted in bitterness at the lackluster reception of Zeitgeist. It's at once a departure and still the most Corgan-ish idea ever. The willingness to work on and present songs as single entities seemed a break in behavior for a band that had always thought in album-length structure, but then it still had this big, maybe-ridiculous overarching concept hanging over the whole thing : thematically, Corgan meant to accompany a return to more psychedelic sounds with some lengthy story inspired by Tarot cards. Teargarden by Kaleidyscope was going to be deployed in a new way, but that was dressing up what was in a lot of ways vintage post-Mellon Collie Smashing Pumpkins behavior.

Initially, the striking thing about the Teargarden project was how much Smashing Pumpkins suddenly sounded entirely like a classic rock band. "A Song for a Son" and "Widow Wake My Mind" were the foremost examples, but even the slightly more typical Pumpkins tune "Astral Planes" rocked with a more specifically late-'60s version of darkened psychedelia than anything Corgan had fully embraced before. These songs would go on to comprise the mostly dry Vol. 1: Songs for a Sailor, the highlight of which was "A Stitch in Time," a simple acoustic song draped in spacey synth lines. There is some variety across the two complete volumes of Teargarden that we have so far, Corgan reincorporating electronic flourishes and New Wave influence into moments of Vol. 2: The Solstice Bare. Some people were into Corgan's new experimentation, but it feels kind of regressive. Where Corgan once looked stubbornly to the future, he was looking to the past now, and wasn't necessarily coming up with any stunning revelations as a result. Most of the Teargarden material feels inessential, and besides "A Stitch in Time" and maybe "The Fellowship," I haven't thought about listening to any of these songs between them being released and me writing this article.

It's perhaps a bit premature to include Teargarden by Kaleidyscope on this list, or, at least, it's hard to qualify exactly what it is. After completing the first two EPs and two standalone songs (enough to qualify for one album's length, though a short one by Pumpkins standards), Corgan & co. decided to temporarily return to a more traditional route, releasing Oceania as a physical album with all the attendant press and tour cycles, though still considering it an entry into the larger Teargarden project. It remains unclear whether the Smashing Pumpkins will finish Teargarden in any form reminiscent of its original conceit — they've already talked about feeling like they're on a streak with Oceania and wanting to get another full-fledged album out soon. Based on how much stronger the material on Oceania turned out to be, maybe it still plays to Corgan's strengths for him to work within the strictures of an album.

After Chamberlin's departure (or, possibly, dismissal) from the reformed Smashing Pumpkins, Corgan envisioned a path forward with an ambitious new recording project. Expressing dissatisfaction with the practice of releasing traditional physical albums on the traditional cycle and dealing with industry mores, Corgan planned to work on one song at a time, crafting each one specifically and releasing them as they were done, eventually leading up to a 44 track project at its completion made up of 11 4-song EPs and possibly a one disc distillation of the best material. This was half respectable, half suspicious — sounding partially rooted in bitterness at the lackluster reception of Zeitgeist. It's at once a departure and still the most Corgan-ish idea ever. The willingness to work on and present songs as single entities seemed a break in behavior for a band that had always thought in album-length structure, but then it still had this big, maybe-ridiculous overarching concept hanging over the whole thing : thematically, Corgan meant to accompany a return to more psychedelic sounds with some lengthy story inspired by Tarot cards. Teargarden by Kaleidyscope was going to be deployed in a new way, but that was dressing up what was in a lot of ways vintage post-Mellon Collie Smashing Pumpkins behavior.

Initially, the striking thing about the Teargarden project was how much Smashing Pumpkins suddenly sounded entirely like a classic rock band. "A Song for a Son" and "Widow Wake My Mind" were the foremost examples, but even the slightly more typical Pumpkins tune "Astral Planes" rocked with a more specifically late-'60s version of darkened psychedelia than anything Corgan had fully embraced before. These songs would go on to comprise the mostly dry Vol. 1: Songs for a Sailor, the highlight of which was "A Stitch in Time," a simple acoustic song draped in spacey synth lines. There is some variety across the two complete volumes of Teargarden that we have so far, Corgan reincorporating electronic flourishes and New Wave influence into moments of Vol. 2: The Solstice Bare. Some people were into Corgan's new experimentation, but it feels kind of regressive. Where Corgan once looked stubbornly to the future, he was looking to the past now, and wasn't necessarily coming up with any stunning revelations as a result. Most of the Teargarden material feels inessential, and besides "A Stitch in Time" and maybe "The Fellowship," I haven't thought about listening to any of these songs between them being released and me writing this article.

It's perhaps a bit premature to include Teargarden by Kaleidyscope on this list, or, at least, it's hard to qualify exactly what it is. After completing the first two EPs and two standalone songs (enough to qualify for one album's length, though a short one by Pumpkins standards), Corgan & co. decided to temporarily return to a more traditional route, releasing Oceania as a physical album with all the attendant press and tour cycles, though still considering it an entry into the larger Teargarden project. It remains unclear whether the Smashing Pumpkins will finish Teargarden in any form reminiscent of its original conceit — they've already talked about feeling like they're on a streak with Oceania and wanting to get another full-fledged album out soon. Based on how much stronger the material on Oceania turned out to be, maybe it still plays to Corgan's strengths for him to work within the strictures of an album.

Oceania was a really pleasant surprise. Nobody expected an album this good from Corgan at the dubious post-Zeitgeist, post-Chamberlin juncture of the Smashing Pumpkins' story. Where in the past Corgan's ego might've seemed justified by the band's accomplishments through the early and mid '90s, by the late '00s it was easy to write Corgan off as a grumpily aging rockstar off at the sidelines, entertaining for the crazy stuff he said but not someone we had much faith in anymore. Oceania came out, widely received positive reviews, and was considered by many to be a return to form. Some called it his best since the Smashing Pumpkins first disbanded, which isn't really saying much considering there's little of worth during that time period aside from the way underrated/wrongfully hated Zwan one-off in 2003. Some called it his best since MACHINA, some since Adore, some even since Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness. And, no doubt, it is the strongest music Corgan has put out in some time, though there is also something about it that doesn't feel quite like the Smashing Pumpkins, perhaps because it's the first album under the band's moniker where Corgan was the sole original member involved.

Posited as an "album within an album" attached to the Teargarden by Kaleidyscope project, Oceania was Corgan's foray back into making albums the traditional way, saying that it helps him focus more, and citing the fact that releasing songs one by one wasn't garnering the kind of attention he wanted for his music. Oceania does feel loosely attached to those Teargarden recordings, its proggy psychedelia still firmly in this whole Smashing Pumpkins-go-classic rock phase. It all just works a lot better here. The songs are sharper and more memorable, Corgan's genre explorations working better over the course of a LP rather than thrown together randomly and seemingly without context on the Teargarden EPs. And regardless of where you stand on the idea of a Smashing Pumpkins reunion comprised solely of Corgan, it seems he'd achieved a sense of balance with Oceania, finally assembling a steady group of new players who actually performed their parts during the recording process.

The result was an album that sounded far more vital than Zeitgeist, and one I found myself listening to a lot more than I expected. Still, I enjoy it akin to how I enjoy Zwan : Corgan's familiar voice and style are there, but there is just something tonally or structurally that doesn't seem to make sense within the world of the Smashing Pumpkins, which makes Zwan cool but Oceania uncomfortable. Corgan himself had thoughts related to this, remarking "It is the first time where you actually hear me escape the old band. I'm not reacting against it or for it or in the shadow of it." That's true, and it's a more positive way of looking at it. There's no denying this is very much a new step for Corgan compared to the stultified Zeitgeist, and I'd be sympathetic to a list that ranked Oceania above, say, the MACHINA albums. But right now, as much as I like the album, its stature in the overall Smashing Pumpkins catalog is a lesser one, partially because I can't shake the sense that this should really just be considered the product of a different group. Outside of those hang-ups, Oceania is a promising release, a signal that Corgan seems to have gotten his inspiration back.

Oceania was a really pleasant surprise. Nobody expected an album this good from Corgan at the dubious post-Zeitgeist, post-Chamberlin juncture of the Smashing Pumpkins' story. Where in the past Corgan's ego might've seemed justified by the band's accomplishments through the early and mid '90s, by the late '00s it was easy to write Corgan off as a grumpily aging rockstar off at the sidelines, entertaining for the crazy stuff he said but not someone we had much faith in anymore. Oceania came out, widely received positive reviews, and was considered by many to be a return to form. Some called it his best since the Smashing Pumpkins first disbanded, which isn't really saying much considering there's little of worth during that time period aside from the way underrated/wrongfully hated Zwan one-off in 2003. Some called it his best since MACHINA, some since Adore, some even since Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness. And, no doubt, it is the strongest music Corgan has put out in some time, though there is also something about it that doesn't feel quite like the Smashing Pumpkins, perhaps because it's the first album under the band's moniker where Corgan was the sole original member involved.

Posited as an "album within an album" attached to the Teargarden by Kaleidyscope project, Oceania was Corgan's foray back into making albums the traditional way, saying that it helps him focus more, and citing the fact that releasing songs one by one wasn't garnering the kind of attention he wanted for his music. Oceania does feel loosely attached to those Teargarden recordings, its proggy psychedelia still firmly in this whole Smashing Pumpkins-go-classic rock phase. It all just works a lot better here. The songs are sharper and more memorable, Corgan's genre explorations working better over the course of a LP rather than thrown together randomly and seemingly without context on the Teargarden EPs. And regardless of where you stand on the idea of a Smashing Pumpkins reunion comprised solely of Corgan, it seems he'd achieved a sense of balance with Oceania, finally assembling a steady group of new players who actually performed their parts during the recording process.

The result was an album that sounded far more vital than Zeitgeist, and one I found myself listening to a lot more than I expected. Still, I enjoy it akin to how I enjoy Zwan : Corgan's familiar voice and style are there, but there is just something tonally or structurally that doesn't seem to make sense within the world of the Smashing Pumpkins, which makes Zwan cool but Oceania uncomfortable. Corgan himself had thoughts related to this, remarking "It is the first time where you actually hear me escape the old band. I'm not reacting against it or for it or in the shadow of it." That's true, and it's a more positive way of looking at it. There's no denying this is very much a new step for Corgan compared to the stultified Zeitgeist, and I'd be sympathetic to a list that ranked Oceania above, say, the MACHINA albums. But right now, as much as I like the album, its stature in the overall Smashing Pumpkins catalog is a lesser one, partially because I can't shake the sense that this should really just be considered the product of a different group. Outside of those hang-ups, Oceania is a promising release, a signal that Corgan seems to have gotten his inspiration back.

I went back and forth for a while on whether to list the MACHINA albums together or separately. Most of this material comes from the same sessions, or at least was conceived as a part of the same long project, but it becomes a question of artistic intent vs. the realities of how these albums were presented and consumed by listeners. Rumor has it that the MACHINA albums will be reissued together, perhaps with their tracks reordered so that they are blended together, but that's not how we first received them. Corgan had pitched the idea of a double album to Virgin who were, after the comparative commercial disappointment of Adore, entirely uninterested in the idea. When MACHINA/The Machines of God was released to an even more muted commercial response and mixed critical reaction, Corgan tried to get Virgin to release MACHINA II, which they also declined. As a result, the band released MACHINA II/The Friends & Enemies of Modern Music independently, for free on the internet. As a result, you wound up with two sister albums that occupy pretty different spaces in terms of exposure and fan assessment, but nevertheless seem inseparable as two halves of one final act.

The main detriment to the MACHINA albums is all the circumstance weighing them down. After Jimmy Chamberlin rejoined the band, Corgan planned to record one more album and break up the Smashing Pumpkins, and MACHINA became a correspondingly vast and all-encompassing project. At this point, the entire band was thoroughly exhausted with the trappings of rock stardom, and Corgan conceived a concept album structure for MACHINA that would be influenced by the exaggerated image of the band that they felt was placed upon them by the music media. So the story goes on about a rockstar named Zero who hears the voice of God and well, who really knows where it ends or why or if anyone cares. Concept albums are dangerous things to begin with, mostly populated by stories that either are too under-realized to make any sense or so ridiculous that you'd rather not be aware of them. MACHINA was born as a concept album but left half-finished and partially abandoned, with Corgan thrown off by Wretzky's sudden departure from the band and maybe losing focus with the knowledge that the Smashing Pumpkins' end was imminent. The final result wound up being an album that was bloated and at some points indistinguishable, not bloated in a mad-eyed, brilliantly diverse way like Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness. MACHINA/The Machines of God seemed to be a prolonged last gasp, representing the weariness of a band that had basically been through the ringer constantly since their inception.

But even with all its flaws and the downbeat note on which it/they ended the Smashing Pumpkins' career for those who had been following along since the start, the MACHINA albums are worth revisiting. Seeking to fuse the electronic sounds of Adore with the structures and aesthetic of their previous work, MACHINA was very much a product of its time — and sounds it — but works surprisingly well. Maybe it can partially be attributed to Corgan and Iha's New Order-indebted beginnings, but the textural interplay between rock and electronic elements on MACHINA make it one of the more interesting Smashing Pumpkins releases. Though it meanders in its second half, the first MACHINA has some of the most gorgeous, darkly atmospheric pop songs the Smashing Pumpkins ever recorded, with underrated cuts like "Raindrops + Sunshowers" and "Try, Try, Try." MACHINA II is the dark horse of the Smashing Pumpkins catalog, a lesser known release that diehards (and those who actually reviewed it) often identify as a lost classic quietly lingering at the end of the Smashing Pumpkins' first phase, one that redeemed MACHINA. And, that's part true — ironically, for a set of leftovers MACHINA II does have a solid structure and flow to it, and many of the songs are more immediate than those on its predecessor. MACHINA II is the more consistent record, but people are also wrong to entirely dismiss the hauntingly twilit dream-pop of the first MACHINA.

MACHINA I & II require a little sifting to discover its best moments, which in a way each Pumpkins record does. There's just a little more murk to wade through here. Sure, there's something to be said for spending time with MACHINA II in favor of MACHINA, or for the idea that if you culled the best of each disc you could have an absolutely brilliant Smashing Pumpkins album, but in true Corgan fashion what we actually have is the big, messy expanse of it. The fact that it has a bleary-eyed knowledge of its existence at the (supposed) end of their career makes it all the more engaging all these years later, post-reunion. It demands a lot of listens to work through everything on both installments of MACHINA, but if you're at all invested in the Smashing Pumpkins it can be a sneakily rewarding listen.

I went back and forth for a while on whether to list the MACHINA albums together or separately. Most of this material comes from the same sessions, or at least was conceived as a part of the same long project, but it becomes a question of artistic intent vs. the realities of how these albums were presented and consumed by listeners. Rumor has it that the MACHINA albums will be reissued together, perhaps with their tracks reordered so that they are blended together, but that's not how we first received them. Corgan had pitched the idea of a double album to Virgin who were, after the comparative commercial disappointment of Adore, entirely uninterested in the idea. When MACHINA/The Machines of God was released to an even more muted commercial response and mixed critical reaction, Corgan tried to get Virgin to release MACHINA II, which they also declined. As a result, the band released MACHINA II/The Friends & Enemies of Modern Music independently, for free on the internet. As a result, you wound up with two sister albums that occupy pretty different spaces in terms of exposure and fan assessment, but nevertheless seem inseparable as two halves of one final act.

The main detriment to the MACHINA albums is all the circumstance weighing them down. After Jimmy Chamberlin rejoined the band, Corgan planned to record one more album and break up the Smashing Pumpkins, and MACHINA became a correspondingly vast and all-encompassing project. At this point, the entire band was thoroughly exhausted with the trappings of rock stardom, and Corgan conceived a concept album structure for MACHINA that would be influenced by the exaggerated image of the band that they felt was placed upon them by the music media. So the story goes on about a rockstar named Zero who hears the voice of God and well, who really knows where it ends or why or if anyone cares. Concept albums are dangerous things to begin with, mostly populated by stories that either are too under-realized to make any sense or so ridiculous that you'd rather not be aware of them. MACHINA was born as a concept album but left half-finished and partially abandoned, with Corgan thrown off by Wretzky's sudden departure from the band and maybe losing focus with the knowledge that the Smashing Pumpkins' end was imminent. The final result wound up being an album that was bloated and at some points indistinguishable, not bloated in a mad-eyed, brilliantly diverse way like Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness. MACHINA/The Machines of God seemed to be a prolonged last gasp, representing the weariness of a band that had basically been through the ringer constantly since their inception.

But even with all its flaws and the downbeat note on which it/they ended the Smashing Pumpkins' career for those who had been following along since the start, the MACHINA albums are worth revisiting. Seeking to fuse the electronic sounds of Adore with the structures and aesthetic of their previous work, MACHINA was very much a product of its time — and sounds it — but works surprisingly well. Maybe it can partially be attributed to Corgan and Iha's New Order-indebted beginnings, but the textural interplay between rock and electronic elements on MACHINA make it one of the more interesting Smashing Pumpkins releases. Though it meanders in its second half, the first MACHINA has some of the most gorgeous, darkly atmospheric pop songs the Smashing Pumpkins ever recorded, with underrated cuts like "Raindrops + Sunshowers" and "Try, Try, Try." MACHINA II is the dark horse of the Smashing Pumpkins catalog, a lesser known release that diehards (and those who actually reviewed it) often identify as a lost classic quietly lingering at the end of the Smashing Pumpkins' first phase, one that redeemed MACHINA. And, that's part true — ironically, for a set of leftovers MACHINA II does have a solid structure and flow to it, and many of the songs are more immediate than those on its predecessor. MACHINA II is the more consistent record, but people are also wrong to entirely dismiss the hauntingly twilit dream-pop of the first MACHINA.

MACHINA I & II require a little sifting to discover its best moments, which in a way each Pumpkins record does. There's just a little more murk to wade through here. Sure, there's something to be said for spending time with MACHINA II in favor of MACHINA, or for the idea that if you culled the best of each disc you could have an absolutely brilliant Smashing Pumpkins album, but in true Corgan fashion what we actually have is the big, messy expanse of it. The fact that it has a bleary-eyed knowledge of its existence at the (supposed) end of their career makes it all the more engaging all these years later, post-reunion. It demands a lot of listens to work through everything on both installments of MACHINA, but if you're at all invested in the Smashing Pumpkins it can be a sneakily rewarding listen.

Given the total explosion of genre borders we now live with, that whole late '90s phase of rock bands going electronic seems kind of quaint. At the time, that seemed to be the wave of the future, and it was a way to challenge yourself and expand your sound. It was also a way to alienate a bunch of fans who'd come for hard rock guitars and were not onboard for albums full of moody synths or wispy acoustic ballads. Depending on who you talked to leading up to the release of Adore — which was the Smashing Pumpkins' follow-up to the mega-successful Mellon Collie & the Infinite Sadness — it was to be the Smashing Pumpkins' techno album, or it was to be their acoustic album. Turns out it was a bit of both but wasn't exactly either, though one thing was certainly true — electric guitars are far more scarce than on previous Smashing Pumpkins releases, and when they did appear it was textural. No more anthems, no more screaming until all the demons had been ejected. Instead, Adore was dark and subdued in almost every way, a blacked out cover and new blacked out aesthetic for the band to fit with the dusky, forlorn night music they'd crafted.

Where many fans were put off by this new direction, critics mainly loved Adore, rightfully noting how it seemed to be the most mature of the Smashing Pumpkins' albums. In the past, Corgan had been up front about writing music focused on the issues young people face, but Adore was an adult album grappling with adult concerns and experiences. It was the first Pumpkins record done without Chamberlin, and one can sense the weight of his absence — and the correlating concern for his wellbeing — throughout. There's a loss at the center of the album, and it was a multi-faceted one. While the band had lost a piece of itself, Corgan had gone through two losses in his personal life : that of his mother and that of his marriage. Adore isn't the pulsating electronic album the hype would lead you to believe. Where synth textures and drum machines do appear they contrast with morose acoustic songs, but only in small gradations. The whole album seems an arrangement of different tones of dilapidated grey, listless in reckoning with so much absence.

Like most late-'90s efforts by the artists that had survived the alt-rock boom, Adore has the sound of growing pains. When it works, it's a gorgeous indulgence in the band's artier side. There are only a few other stretches in the Smashing Pumpkins' catalog as strong as the first four tracks here. The sparse "To Sheila" wooing you into the world of Adore before the excellent "Ava Adore" throbs to life, the lachrymose pop of "Perfect" yielding to "Daphne Descends," which manages to use a few well placed synth drones to achieve a much darker mood than the heaviest Smashing Pumpkins rock songs. The rest varies in quality, but much of Adore is beautiful and intriguing, and you can't help but start to feel like even the good post-2000 work from Corgan is not on the same level of thought or maturity as exists here. Of course, how much you can get into Adore will depend entirely on what kind of Smashing Pumpkins fan you are. After the magnanimity of Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness, Adore feels like a deeply personal album, one where Corgan was channeling the pain of that specific moment. One he had to make. It's not the most essential Smashing Pumpkins album, and it's a far more specific listening experience than the earlier albums, but it's worth spending some time here.

Given the total explosion of genre borders we now live with, that whole late '90s phase of rock bands going electronic seems kind of quaint. At the time, that seemed to be the wave of the future, and it was a way to challenge yourself and expand your sound. It was also a way to alienate a bunch of fans who'd come for hard rock guitars and were not onboard for albums full of moody synths or wispy acoustic ballads. Depending on who you talked to leading up to the release of Adore — which was the Smashing Pumpkins' follow-up to the mega-successful Mellon Collie & the Infinite Sadness — it was to be the Smashing Pumpkins' techno album, or it was to be their acoustic album. Turns out it was a bit of both but wasn't exactly either, though one thing was certainly true — electric guitars are far more scarce than on previous Smashing Pumpkins releases, and when they did appear it was textural. No more anthems, no more screaming until all the demons had been ejected. Instead, Adore was dark and subdued in almost every way, a blacked out cover and new blacked out aesthetic for the band to fit with the dusky, forlorn night music they'd crafted.

Where many fans were put off by this new direction, critics mainly loved Adore, rightfully noting how it seemed to be the most mature of the Smashing Pumpkins' albums. In the past, Corgan had been up front about writing music focused on the issues young people face, but Adore was an adult album grappling with adult concerns and experiences. It was the first Pumpkins record done without Chamberlin, and one can sense the weight of his absence — and the correlating concern for his wellbeing — throughout. There's a loss at the center of the album, and it was a multi-faceted one. While the band had lost a piece of itself, Corgan had gone through two losses in his personal life : that of his mother and that of his marriage. Adore isn't the pulsating electronic album the hype would lead you to believe. Where synth textures and drum machines do appear they contrast with morose acoustic songs, but only in small gradations. The whole album seems an arrangement of different tones of dilapidated grey, listless in reckoning with so much absence.

Like most late-'90s efforts by the artists that had survived the alt-rock boom, Adore has the sound of growing pains. When it works, it's a gorgeous indulgence in the band's artier side. There are only a few other stretches in the Smashing Pumpkins' catalog as strong as the first four tracks here. The sparse "To Sheila" wooing you into the world of Adore before the excellent "Ava Adore" throbs to life, the lachrymose pop of "Perfect" yielding to "Daphne Descends," which manages to use a few well placed synth drones to achieve a much darker mood than the heaviest Smashing Pumpkins rock songs. The rest varies in quality, but much of Adore is beautiful and intriguing, and you can't help but start to feel like even the good post-2000 work from Corgan is not on the same level of thought or maturity as exists here. Of course, how much you can get into Adore will depend entirely on what kind of Smashing Pumpkins fan you are. After the magnanimity of Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness, Adore feels like a deeply personal album, one where Corgan was channeling the pain of that specific moment. One he had to make. It's not the most essential Smashing Pumpkins album, and it's a far more specific listening experience than the earlier albums, but it's worth spending some time here.

Pisces Iscariot is a collection of b-sides and rarities, but it feels unfair to exclude it from this list. It looms large in the band's discography in both commercial presence and fan estimation, offering up a bunch of extras from what many still consider the band's prime. It turns out the leftovers rival the stuff that had already seen official release. Maybe it was riding the wave of the success of Siamese Dream, but Pisces Iscariot was also a major commercial hit in its own right — particularly for the sort of release it is — attaining platinum status less than two months after its release. Part of that also has to be attributed to the band's cover of Fleetwood Mac's "Landslide," still one of their calling cards for those who were primarily aware of the Smashing Pumpkins by hearing them on the radio.

While "Landslide" stands out as one of the collection's more recognizable tracks, Pisces Iscariot is littered with lost gems. As far as b-sides collections go, it's not all that revelatory in the sense that it's not like it exposes some other direction the band could have taken. At that point, only Gish and Siamese Dream had been released, and much of the material here hews fairly closely to the parameters set out by those two albums. Pisces Iscariot mainly splits its time between fuzzed out rockers and denser, more psychedelic tracks. One difference you could argue for is that this psychedelic influence might be heightened here than it was on either of the finished Smashing Pumpkins albums that had seen release thus far, resulting in spiraling fan favorites like "Starla" as well as a blissed-out, hushed ballad side ("Obscured," "Whir"). If Gish and Siamese Dream weren't so unimpeachable as is, Corgan would seem crazy for leaving tracks like "La Dolly Vita" or "Hello Kitty Kat" off their albums, and you could probably still make a strong argument about it. What we do have is a collection of material so strong as to almost feel like a bonus album altogether, with Pisces Iscariot remaining as good as many actual albums released in the '90s, and another essential entry into the Smashing Pumpkins' early peak years.

Pisces Iscariot is a collection of b-sides and rarities, but it feels unfair to exclude it from this list. It looms large in the band's discography in both commercial presence and fan estimation, offering up a bunch of extras from what many still consider the band's prime. It turns out the leftovers rival the stuff that had already seen official release. Maybe it was riding the wave of the success of Siamese Dream, but Pisces Iscariot was also a major commercial hit in its own right — particularly for the sort of release it is — attaining platinum status less than two months after its release. Part of that also has to be attributed to the band's cover of Fleetwood Mac's "Landslide," still one of their calling cards for those who were primarily aware of the Smashing Pumpkins by hearing them on the radio.

While "Landslide" stands out as one of the collection's more recognizable tracks, Pisces Iscariot is littered with lost gems. As far as b-sides collections go, it's not all that revelatory in the sense that it's not like it exposes some other direction the band could have taken. At that point, only Gish and Siamese Dream had been released, and much of the material here hews fairly closely to the parameters set out by those two albums. Pisces Iscariot mainly splits its time between fuzzed out rockers and denser, more psychedelic tracks. One difference you could argue for is that this psychedelic influence might be heightened here than it was on either of the finished Smashing Pumpkins albums that had seen release thus far, resulting in spiraling fan favorites like "Starla" as well as a blissed-out, hushed ballad side ("Obscured," "Whir"). If Gish and Siamese Dream weren't so unimpeachable as is, Corgan would seem crazy for leaving tracks like "La Dolly Vita" or "Hello Kitty Kat" off their albums, and you could probably still make a strong argument about it. What we do have is a collection of material so strong as to almost feel like a bonus album altogether, with Pisces Iscariot remaining as good as many actual albums released in the '90s, and another essential entry into the Smashing Pumpkins' early peak years.

The Smashing Pumpkins' debut was released May 28, 1991. Three months before Pearl Jam released Ten, four months before Nirvana released Nevermind, five months before Soundgarden released Badmotorfinger. Despite Gish garnering a much more visible critical and commercial reaction than had been anticipated, it still didn't have the profile and reach of these later, more iconic releases, and the Smashing Pumpkins wouldn't escape being labeled the "next Nirvana" or the "next Pearl Jam" along their own rise to superstardom. It would take Siamese Dream for the band to truly stake out their own territory, though Gish remains one of the band's classics and is stacked with fan favorites.

Described by Corgan as a "spiritual album," Gish can come off as one of those albums that seeks transcendence in layers of distorted guitars or careful drum builds breaking into cathartic solo sections. While each of the major '90s alt rock artists worked off their own particular blend of genres, even from this early date the Smashing Pumpkins seemed to draw from a wider palette and combine strains of genres that would seem to have nothing to do with each other on paper. Gish is at once one of their most aggressive releases — the guitars and drums have a pent-up fury that seems younger and more reckless than the meticulously cultivated bite of later songs — and one of their spaciest. Meditative tracks like "Crush" and "Suffer" hide within the maelstroms kicked up by "I Am One" and "Bury Me," while songs like "Rhinoceros" have a foot in both worlds, beginning in their own sadly trippy revery before exploding outwards and upwards.

In many ways, Gish set the template for what was to come. Establishing his dictatorial reputation from the start, Corgan was already playing a lot of the guitar and bass parts himself, fixating over finding the exact sound he wanted with producer Butch Vig. As a result, the recording of Gish became the genesis of the host of interpersonal conflict that would plague the band throughout its existence, as Iha and Wretzky became dissatisfied with their lack of inclusion in the process. For Corgan, it needed to be this way in order for him to attain his vision for Gish, but it also nearly broke him, driving him into a nervous breakdown. This kind of tumultuousness would become a perennial element of the Smashing Pumpkins narrative, but often made for some of their most rewarding and expansive music. Where Gish has all that same intensity and emotional purging that'd characterize the next few albums, it also has a relative restraint, Corgan not yet given the free range and budget with which he'd realize his big-screen ambitions later. For some fans, Gish is still a — or maybe even "the" — high-water mark in the Smashing Pumpkins' catalog, and it is one of the slightly lesser-acknowledged classics of that rising alt wave of '91. It also seems very rooted in its circumstances, a grunge-leaning alternative album that had the Smashing Pumpkins DNA already figured out, but not fleshed out. Corgan's most ambitious visions would at times sink the band, but along the way they'd produce highs not yet heard on Gish.

The Smashing Pumpkins' debut was released May 28, 1991. Three months before Pearl Jam released Ten, four months before Nirvana released Nevermind, five months before Soundgarden released Badmotorfinger. Despite Gish garnering a much more visible critical and commercial reaction than had been anticipated, it still didn't have the profile and reach of these later, more iconic releases, and the Smashing Pumpkins wouldn't escape being labeled the "next Nirvana" or the "next Pearl Jam" along their own rise to superstardom. It would take Siamese Dream for the band to truly stake out their own territory, though Gish remains one of the band's classics and is stacked with fan favorites.

Described by Corgan as a "spiritual album," Gish can come off as one of those albums that seeks transcendence in layers of distorted guitars or careful drum builds breaking into cathartic solo sections. While each of the major '90s alt rock artists worked off their own particular blend of genres, even from this early date the Smashing Pumpkins seemed to draw from a wider palette and combine strains of genres that would seem to have nothing to do with each other on paper. Gish is at once one of their most aggressive releases — the guitars and drums have a pent-up fury that seems younger and more reckless than the meticulously cultivated bite of later songs — and one of their spaciest. Meditative tracks like "Crush" and "Suffer" hide within the maelstroms kicked up by "I Am One" and "Bury Me," while songs like "Rhinoceros" have a foot in both worlds, beginning in their own sadly trippy revery before exploding outwards and upwards.

In many ways, Gish set the template for what was to come. Establishing his dictatorial reputation from the start, Corgan was already playing a lot of the guitar and bass parts himself, fixating over finding the exact sound he wanted with producer Butch Vig. As a result, the recording of Gish became the genesis of the host of interpersonal conflict that would plague the band throughout its existence, as Iha and Wretzky became dissatisfied with their lack of inclusion in the process. For Corgan, it needed to be this way in order for him to attain his vision for Gish, but it also nearly broke him, driving him into a nervous breakdown. This kind of tumultuousness would become a perennial element of the Smashing Pumpkins narrative, but often made for some of their most rewarding and expansive music. Where Gish has all that same intensity and emotional purging that'd characterize the next few albums, it also has a relative restraint, Corgan not yet given the free range and budget with which he'd realize his big-screen ambitions later. For some fans, Gish is still a — or maybe even "the" — high-water mark in the Smashing Pumpkins' catalog, and it is one of the slightly lesser-acknowledged classics of that rising alt wave of '91. It also seems very rooted in its circumstances, a grunge-leaning alternative album that had the Smashing Pumpkins DNA already figured out, but not fleshed out. Corgan's most ambitious visions would at times sink the band, but along the way they'd produce highs not yet heard on Gish.

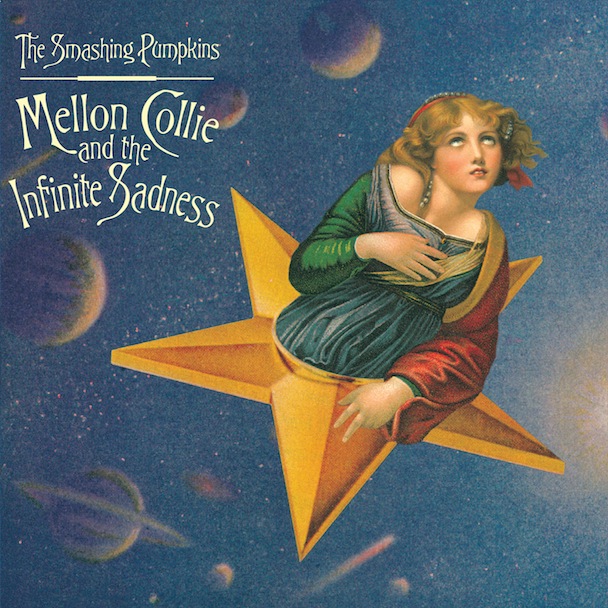

In a discography full of overwhelming and overblown albums, nothing else by the Smashing Pumpkins matches the dizzying and gloriously overstuffed heights of Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness. Occasionally described by Corgan as "The Wall for Generation X" and also identifying The White Album as a touchstone, the ambitions of Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness are clear : Siamese Dream would be the album that broke them to the world, but Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness would be their masterwork, the one that looked back to the most extreme accomplishments of the classic rock firmament to seek inclusion into that same firmament. In the years since, Siamese Dream has probably lived on as the single most important album in the Smashing Pumpkins' career, but that's not to dismiss what the band intended to do with Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness, or the fact that they actually achieved it. Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness is a massive album, one that demands a lot of time, investment, and attention from the listener. It was also a massive album, period : earning the band some of its biggest singles, going on to become certified diamond by the RIAA. Just like the albums it aimed to emulate, it was a stratospheric rock success, the rare double album that even it all its evident excess felt like it needed to be that way.

Fittingly, the sheer amount of material came accompanied with Corgan's first real gestures at concept album structuring. Mellon Collie's two discs were split into Day and Night sections, each intended to mirror the other. Throughout, Corgan sought to give voice to all the frustrations he'd held over the years but never been able to express. "I'm waving goodbye to me in the rearview mirror, tying a knot around my youth and putting it under the bed," he commented, elaborating that he channeled the anxieties of his youth into one final album intended for listeners in their teens and early twenties. Accompanying this would, fittingly, be a set of songs that seemed to be everything the band could possibly offer. Where Gish and Siamese Dream had suggested a wide array of styles collapsed into one distinctive sound, Mellon Collie took all of Corgan's stray interests and blew them out over its 28 tracks.

Of course, there were rock songs. Some of the band's most recognizable ones, given that "Bullet with Butterfly Wings" is on here. They pushed this side of their personality to its outer limits, though, not being anthemic as on past songs like "Cherub Rock," but instead becoming caustic on "Zero" or "X.Y.U." and straight up corrosive on "Tales of a Scorched Earth." In contrast, there were some of the band's gentlest songs in the otherworldly "Cupid de Locke" and "Thirty-Three." There was art-rock and heavy metal sandwiched together. There was their most unabashed, straightforward pop in "1979" (one of their finest moments) and a set of epics in the twin peaks of the ethereal drama of "Porcelina of the Vast Oceans" and "Thru the Eyes of Ruby" (a close contender for my favorite Smashing Pumpkins song). Those songs are little microcosms of all the insane detail put into this album, "Thru the Eyes of Ruby" alone comprised of something around 70 guitar tracks.

After all that, something had to break, you'd have to guess. Part of it was personal : Chamberlin suffered a heroin overdose during the massive tour in support of Mellon Collie, and was dismissed from the band. They decided to continue touring, a decision Corgan would later single out as one of the biggest mistakes he'd made in the band's history. As frayed as they might've been in their own lives, from an artistic standpoint Mellon Collie marked an inevitable endpoint. The Smashing Pumpkins had already hinted that they were growing dissatisfied with rock music alone. "The future is in electronic music. It really seems boring to just play rock music," Iha remarked during this time, and you could already hear experimentation creeping into songs like "Love," "Beautiful," and "1979." Mellon Collie would be the last moment where the band experienced rampant success and near-unanimous acclaim ; every left turn or double back that followed would irk some contingency of fans or critics somewhere. But what else could they have done after Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness? Once you've gone to seemingly every possible corner of your craft, where do you go next? The Smashing Pumpkins had pulled off one of the most ambitious, accomplished albums of this scope. The only option was to seek out undiscovered territory.

In a discography full of overwhelming and overblown albums, nothing else by the Smashing Pumpkins matches the dizzying and gloriously overstuffed heights of Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness. Occasionally described by Corgan as "The Wall for Generation X" and also identifying The White Album as a touchstone, the ambitions of Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness are clear : Siamese Dream would be the album that broke them to the world, but Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness would be their masterwork, the one that looked back to the most extreme accomplishments of the classic rock firmament to seek inclusion into that same firmament. In the years since, Siamese Dream has probably lived on as the single most important album in the Smashing Pumpkins' career, but that's not to dismiss what the band intended to do with Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness, or the fact that they actually achieved it. Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness is a massive album, one that demands a lot of time, investment, and attention from the listener. It was also a massive album, period : earning the band some of its biggest singles, going on to become certified diamond by the RIAA. Just like the albums it aimed to emulate, it was a stratospheric rock success, the rare double album that even it all its evident excess felt like it needed to be that way.

Fittingly, the sheer amount of material came accompanied with Corgan's first real gestures at concept album structuring. Mellon Collie's two discs were split into Day and Night sections, each intended to mirror the other. Throughout, Corgan sought to give voice to all the frustrations he'd held over the years but never been able to express. "I'm waving goodbye to me in the rearview mirror, tying a knot around my youth and putting it under the bed," he commented, elaborating that he channeled the anxieties of his youth into one final album intended for listeners in their teens and early twenties. Accompanying this would, fittingly, be a set of songs that seemed to be everything the band could possibly offer. Where Gish and Siamese Dream had suggested a wide array of styles collapsed into one distinctive sound, Mellon Collie took all of Corgan's stray interests and blew them out over its 28 tracks.

Of course, there were rock songs. Some of the band's most recognizable ones, given that "Bullet with Butterfly Wings" is on here. They pushed this side of their personality to its outer limits, though, not being anthemic as on past songs like "Cherub Rock," but instead becoming caustic on "Zero" or "X.Y.U." and straight up corrosive on "Tales of a Scorched Earth." In contrast, there were some of the band's gentlest songs in the otherworldly "Cupid de Locke" and "Thirty-Three." There was art-rock and heavy metal sandwiched together. There was their most unabashed, straightforward pop in "1979" (one of their finest moments) and a set of epics in the twin peaks of the ethereal drama of "Porcelina of the Vast Oceans" and "Thru the Eyes of Ruby" (a close contender for my favorite Smashing Pumpkins song). Those songs are little microcosms of all the insane detail put into this album, "Thru the Eyes of Ruby" alone comprised of something around 70 guitar tracks.

After all that, something had to break, you'd have to guess. Part of it was personal : Chamberlin suffered a heroin overdose during the massive tour in support of Mellon Collie, and was dismissed from the band. They decided to continue touring, a decision Corgan would later single out as one of the biggest mistakes he'd made in the band's history. As frayed as they might've been in their own lives, from an artistic standpoint Mellon Collie marked an inevitable endpoint. The Smashing Pumpkins had already hinted that they were growing dissatisfied with rock music alone. "The future is in electronic music. It really seems boring to just play rock music," Iha remarked during this time, and you could already hear experimentation creeping into songs like "Love," "Beautiful," and "1979." Mellon Collie would be the last moment where the band experienced rampant success and near-unanimous acclaim ; every left turn or double back that followed would irk some contingency of fans or critics somewhere. But what else could they have done after Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness? Once you've gone to seemingly every possible corner of your craft, where do you go next? The Smashing Pumpkins had pulled off one of the most ambitious, accomplished albums of this scope. The only option was to seek out undiscovered territory.

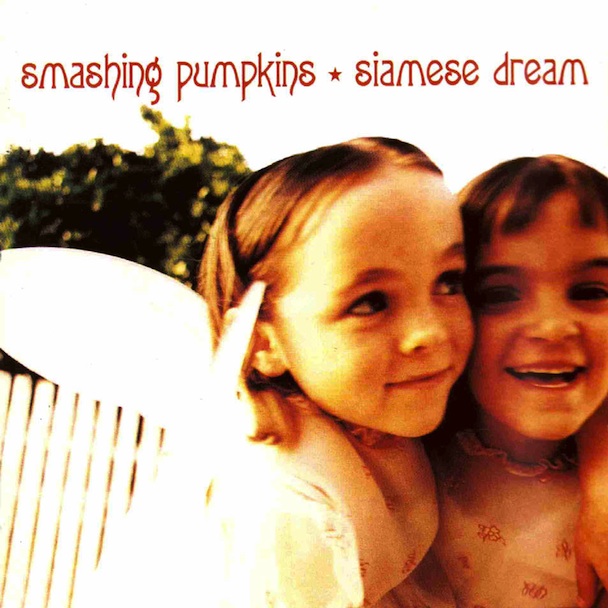

The first minute of Siamese Dream is one of the most perfect things that exists in rock music. That clean guitar rhythm comes in, and you immediately know it's a feint, a suspicion confirmed when that ungodly wall of distortion drops down for the first time. It'd seem that you already went from point A to point B, the stutter of that intro giving way to the deliberate stomp of what will become the verse. But the riff hasn't actually come in yet. First you get eighteen seconds of just this noise that's ratcheting up tension in a way where you can't really picture exactly how it could be alleviated. Then, at around the thirty-eight second mark, Corgan defies the assumption that all of alt-rock is unsexy and somber and kicks into that riff. I am talking about the obliterated but defiant swagger that is "Cherub Rock." I am talking about one of the best guitar lines of the '90s (or, well, maybe ever), one of those immortal riffs that you put on to get amped up or to cure yourself. That you put on when you wake up and it's just one of those mornings and as you walk or drive to work you need the kind of insurmountable distortion that trumps anything else in your way. I'm talking about one of the most perfectly calibrated minutes of music that I can think of, and I'm talking about the moment where Corgan finally enters at the fifty-seven second mark and it's not a scream or a growl, but a coo.

The reason I'm fixating on "Cherub Rock" is because I'll submit that it's one of the best openers ever, period, but also for two other reasons. First, it might still be the best, most quintessential Smashing Pumpkins song out there. It's guitar-heroic in that typical '90s way of being anti-guitar-heroic, so overdriven as to hardly sound like an instrument anymore. But then it's traditionally guitar-heroic, too, because there's a big anthemic solo dropped in the middle. It rails against outside forces, but it also seems like a deep interrogation of Corgan's psyche. In five minutes — a brief sprint, considering the verbosity they'd later develop — it seems to sum up everything that was engaging and exciting about this band. It welcomes you into the world of the Smashing Pumpkins, and it does it in a way that's open enough for you to derive whatever you need from it. I didn't even know it was about Corgan's problematic relationship with the rest of the early '90s indie world until this week.

These kinds of albums don't come easily. Siamese Dream was the sum total of a lot of bad stuff for a young band to have already gone through : Chamberlin's drug abuse was already in full bloom, Iha and Wretzky had gone through a tempestuous breakup but both remained in the band, Corgan was struggling with depression and suicidal thoughts and locking himself in the studio to cope. It was maybe the genesis point for Corgan's reputation as a megalomaniacal control freak, once reports trickled out that his intense perfectionism had caused him to record much of the bass and guitar parts himself. Of course, there's something romantic about that tortured genius archetype, and I think there's something inherent to American culture that draws us to a visionary. It's only later, when the products diminish but the ego doesn't, when we turn on them, and that's happened with Corgan over the years, when his arrogance seemed wholly out of touch with how uneven his legacy has become. You know what, though? I don't even care. Even if (or maybe especially if) the Smashing Pumpkins had only recorded Gish and Siamese Dream, this album would probably still be legendary, and they would've already given us more than we deserve.

Like many classic albums, Siamese Dream is more or less perfect, near-impossible to imagine with anything else added or subtracted. The other reason I fixate on "Cherub Rock" is that it happens to be my perfect moment on Siamese Dream, but I would totally accept someone else going off about some other minute in the depths of the album. Those last thirty seconds of "Today," those are also perfect. The whole last minute of "Rocket," once Corgan starts saying "I shall be free," that part slays me. The serene segue of "Sweet Sweet," that can be perfect, too. For me, though, the other twin pillar of everything there is to the Smashing Pumpkins will forever be "Soma," a song I find so overwhelming that I hardly have words for it. Many other fans would cite "Mayonnaise," and they'd be totally right, too. What I'm trying to say, I guess, is that Siamese Dream is one of those albums that you can't help but feel once it has its grip on you. It's vicarious catharsis, it's a place to belong. But maybe most importantly, it's shelter. More so than an album you listen to, it's an album you turn to. Whatever the reasons were, you'll forget them by the end of that first minute.

The first minute of Siamese Dream is one of the most perfect things that exists in rock music. That clean guitar rhythm comes in, and you immediately know it's a feint, a suspicion confirmed when that ungodly wall of distortion drops down for the first time. It'd seem that you already went from point A to point B, the stutter of that intro giving way to the deliberate stomp of what will become the verse. But the riff hasn't actually come in yet. First you get eighteen seconds of just this noise that's ratcheting up tension in a way where you can't really picture exactly how it could be alleviated. Then, at around the thirty-eight second mark, Corgan defies the assumption that all of alt-rock is unsexy and somber and kicks into that riff. I am talking about the obliterated but defiant swagger that is "Cherub Rock." I am talking about one of the best guitar lines of the '90s (or, well, maybe ever), one of those immortal riffs that you put on to get amped up or to cure yourself. That you put on when you wake up and it's just one of those mornings and as you walk or drive to work you need the kind of insurmountable distortion that trumps anything else in your way. I'm talking about one of the most perfectly calibrated minutes of music that I can think of, and I'm talking about the moment where Corgan finally enters at the fifty-seven second mark and it's not a scream or a growl, but a coo.

The reason I'm fixating on "Cherub Rock" is because I'll submit that it's one of the best openers ever, period, but also for two other reasons. First, it might still be the best, most quintessential Smashing Pumpkins song out there. It's guitar-heroic in that typical '90s way of being anti-guitar-heroic, so overdriven as to hardly sound like an instrument anymore. But then it's traditionally guitar-heroic, too, because there's a big anthemic solo dropped in the middle. It rails against outside forces, but it also seems like a deep interrogation of Corgan's psyche. In five minutes — a brief sprint, considering the verbosity they'd later develop — it seems to sum up everything that was engaging and exciting about this band. It welcomes you into the world of the Smashing Pumpkins, and it does it in a way that's open enough for you to derive whatever you need from it. I didn't even know it was about Corgan's problematic relationship with the rest of the early '90s indie world until this week.

These kinds of albums don't come easily. Siamese Dream was the sum total of a lot of bad stuff for a young band to have already gone through : Chamberlin's drug abuse was already in full bloom, Iha and Wretzky had gone through a tempestuous breakup but both remained in the band, Corgan was struggling with depression and suicidal thoughts and locking himself in the studio to cope. It was maybe the genesis point for Corgan's reputation as a megalomaniacal control freak, once reports trickled out that his intense perfectionism had caused him to record much of the bass and guitar parts himself. Of course, there's something romantic about that tortured genius archetype, and I think there's something inherent to American culture that draws us to a visionary. It's only later, when the products diminish but the ego doesn't, when we turn on them, and that's happened with Corgan over the years, when his arrogance seemed wholly out of touch with how uneven his legacy has become. You know what, though? I don't even care. Even if (or maybe especially if) the Smashing Pumpkins had only recorded Gish and Siamese Dream, this album would probably still be legendary, and they would've already given us more than we deserve.

Like many classic albums, Siamese Dream is more or less perfect, near-impossible to imagine with anything else added or subtracted. The other reason I fixate on "Cherub Rock" is that it happens to be my perfect moment on Siamese Dream, but I would totally accept someone else going off about some other minute in the depths of the album. Those last thirty seconds of "Today," those are also perfect. The whole last minute of "Rocket," once Corgan starts saying "I shall be free," that part slays me. The serene segue of "Sweet Sweet," that can be perfect, too. For me, though, the other twin pillar of everything there is to the Smashing Pumpkins will forever be "Soma," a song I find so overwhelming that I hardly have words for it. Many other fans would cite "Mayonnaise," and they'd be totally right, too. What I'm trying to say, I guess, is that Siamese Dream is one of those albums that you can't help but feel once it has its grip on you. It's vicarious catharsis, it's a place to belong. But maybe most importantly, it's shelter. More so than an album you listen to, it's an album you turn to. Whatever the reasons were, you'll forget them by the end of that first minute.