What an enviable position in which Steven Patrick Morrissey finds himself. It is, I dare say, quite privileged, but we'll get back to that. He is a spokesman for Morrissey alone: not for a bygone era of guitar-spined indie pop; not for the Cool Britannia movement that emerged, like a cicada swarm, from Morrissey's fixation on the England of his youth. He essentially walked away from the mysterious destruction of his creative partnership with Johnny Marr with nary a speck on his blouse. During their five-year tenure, the Smiths parked two singles -- "Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now" and "Sheila Take a Bow" -- at No. 10. Each of Morrissey's first four singles peaked no lower than 9; he has had 10 UK Top Tens as a solo act while notching two US Modern Rock No. 1s, one of which ("The More You Ignore Me, The Closer I Get") scraped into the top half of the Hot 100. Despite his estrangement from a master synthesist -- the man responsible for the Smiths' silken sonic embroidery -- he emerged with his image fully intact. Even better, he was set free: to present himself in new stylistic contexts, to say whatever shit he pleased without bandmate blowback.

Perhaps the one thing stronger than any desire to speak for the outsider or become a British chart fixture is Morrissey's curatorial impulse. Even wayward pilgrims on the Mecca of Moz recognize many of the stations: the gladioli, the National Health glasses, cover art taken from movies of the '50s and '60s, that quiff, asexuality, vegetarianism. Jobriath and Bardot and the Dolls. Critics tear their sheets apart dreaming of the tastemaker status his fanbase accords him. His powers of curation even apply to public statements and interviews: He has done and he has said stupid things, and they have been wished away as masterful acts of irony. Lord only knows what it's like to be a clever boy, poked by the press, wishing to poke back. Lennon developed a hardy persecution complex; Morrissey maintained an address book well-stocked with lawyers.

As usual, Morrissey's problematic actions -- the anti-immigration sentiments, the asinine dismissal of dance music and modern R&B performers, the casual manner in which he knocked around tough-guy skinhead imagery -- make more sense in the context of his native medium. Slagged as the Pope of Mope from the first LP, his lyrical gifts eluded many of his critics and a fair number of his devotees. His first-generation Stateside fans, sulking in their bedrooms, imagined their fey idol doing the same. But Morrissey sprang himself from the confines of home (with more than a little help from Marr), and anyway, even when he was at home, he was dashing off letters to music mags, touting his glammy idols.

Glam may well be the key to unlocking Morrissey. The buzz trail laid by punk acts like the Sex Pistols, which enthralled so many other Mancunian teens, never truly captured his fancy. Punk and glam were both attempts to tease new dialects out of rock and roll; punk focused on rage and resentment (which Morrissey shared), but glam offered the chance to turn one's privilege inside-out, to be louche and beguiling, even while you're offering the same four-chord come-ons. Young Steven filed these provocations away, demonstrating the rigor of his studies in ways both straightforward (offering his body to the world's gaze, supplanting Marr's Nashville tuning with rockabilly twang) and subtle (fixing an eye on what something -- himself, you, Manchester, history -- is and is not). Far from a gothic loller, wishing for supremely melodramatic fatality, Morrissey was (and is) a gifted chronicler of bygone sensations, familiar insecurities and easily accessed angers. Always prone to contradiction rather than clarification, Morrissey was pleased to wreak havoc on his native press, then escape to the unqualified embrace of a worldwide fanbase.

As a vocal stylist, Morrissey is given to quotes, not hooks. Leaving the specifics of structure to his collaborators, he's free to approach the track crosswise, extending verses, splicing bridges and linking phrases into the oddest places. A singer of decidedly limited capability at the start of his career (the Smiths or a brief stint fronting Slaughter and the Dogs: take your pick), he worked tirelessly to broaden his range. At the age of 50, he's more commanding than ever. Knowing he could never replace Marr, he largely punted on the task, adding glam, orchestral bombast and straight-ahead rock to his repertoire. As the man once said, that's how people grow up. To many, Morrissey will forever be the prince of the misfits, but a cursory scan of his output shows a man forever twisting and gnarling the meaning of love, loneliness, and memory.

With his new autobiography finally in stores, it's an apt time to delve into Morrissey's catalog as a solo artist. But really, there's no bad time to talk about Morrissey.

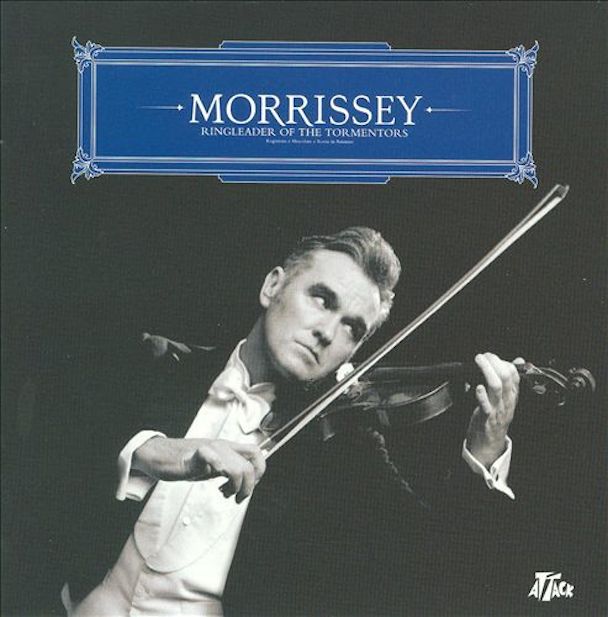

As for Ennio, his contribution is slotted second. "Dear God, Please Help Me" plays like a sacrelicious Righteous Brothers tune, the singer tremulously spreading his legs, ponderous organ cast aside for "Ebb Tide" strings. The tunes with the choir form a triptych of childhood; the guests are served well only on "The Father Who Must Be Killed." Here, upon the kid-friendliest melody and low-end that boxes the speakers, they merely echo their employer. "At Last I Am Born" rides in on a municipal orchestra, Morrissey astride Jobriath’s comet tail, muttering into echo, pausing for fake castanets. Further touches are unnecessary. Likewise the night-spattered "The Youngest Was the Most Loved," a cross between Blue Öyster Cult and Dave Matthews Band’s "Crush". The addition of keening youths sends the track off the "Dear God" cliff.

If not quite a return to his more rockin’ days, Ringleader offers major sonic density. Bassist Gary Day -- an on-and-off collaborator since Your Arsenal -- tries his best to dispel the rain EFX on the vaguely psychedelic "Life Is a Pigsty" with thudding accompaniment. Morrissey tries to keep up with the twin-guitar chime and "Uninvited"-style passages of the Tobias co-write "On the Streets I Ran". Day puts over "To Me You Are a Work of Art," his boss’s newest entry into the love-song sweepstakes. Offering himself to abandon, Moz turns a potential joke song ("and I would give you my heart/that’s if I had one") into a playful communiqué, hammered home by one violin.

His first LP to crack fifty minutes, Ringleader benefits from committed performances and a general lack of chips on shoulders. Lead single "You Have Killed Me" -- tying his chart best with a third-place showing -- is the best example. Sly references to keys, entering and being entered are waved away with a gobsmacked chorus and bridge, and further buried with the earnest declaration of forgiveness. If sometimes Morrissey’s instincts betrayed him, well, it wouldn’t be the first time.

Not even Steven Patrick Morrissey can maintain an immunity to pre-release buzz. The initial recording session, with Jeff Saltzman in Rome, had to be scrapped, and the backup was Tony Visconti, of Bowie and Bolan fame. Visconti, in turn, gleefully tipped the inclusion of Ennio Morricone and an Italian children’s choir. Add the songwriting and third-guitar contributions of Jesse Tobias (erstwhile Frusciante replacement and Jagged Little Pill touring guitarist), and the stage was set for more than a dutiful follow-up. Unfortunately, the more apt leadoff ("In the Future When All’s Well") was ignored in favor of "I Will See You In Far Off Places," which works a rumbling Eastern mode to less effect than Alanis’ post-Jagged prime.

As for Ennio, his contribution is slotted second. "Dear God, Please Help Me" plays like a sacrelicious Righteous Brothers tune, the singer tremulously spreading his legs, ponderous organ cast aside for "Ebb Tide" strings. The tunes with the choir form a triptych of childhood; the guests are served well only on "The Father Who Must Be Killed." Here, upon the kid-friendliest melody and low-end that boxes the speakers, they merely echo their employer. "At Last I Am Born" rides in on a municipal orchestra, Morrissey astride Jobriath’s comet tail, muttering into echo, pausing for fake castanets. Further touches are unnecessary. Likewise the night-spattered "The Youngest Was the Most Loved," a cross between Blue Öyster Cult and Dave Matthews Band’s "Crush". The addition of keening youths sends the track off the "Dear God" cliff.

If not quite a return to his more rockin’ days, Ringleader offers major sonic density. Bassist Gary Day -- an on-and-off collaborator since Your Arsenal -- tries his best to dispel the rain EFX on the vaguely psychedelic "Life Is a Pigsty" with thudding accompaniment. Morrissey tries to keep up with the twin-guitar chime and "Uninvited"-style passages of the Tobias co-write "On the Streets I Ran". Day puts over "To Me You Are a Work of Art," his boss’s newest entry into the love-song sweepstakes. Offering himself to abandon, Moz turns a potential joke song ("and I would give you my heart/that’s if I had one") into a playful communiqué, hammered home by one violin.

His first LP to crack fifty minutes, Ringleader benefits from committed performances and a general lack of chips on shoulders. Lead single "You Have Killed Me" -- tying his chart best with a third-place showing -- is the best example. Sly references to keys, entering and being entered are waved away with a gobsmacked chorus and bridge, and further buried with the earnest declaration of forgiveness. If sometimes Morrissey’s instincts betrayed him, well, it wouldn’t be the first time.

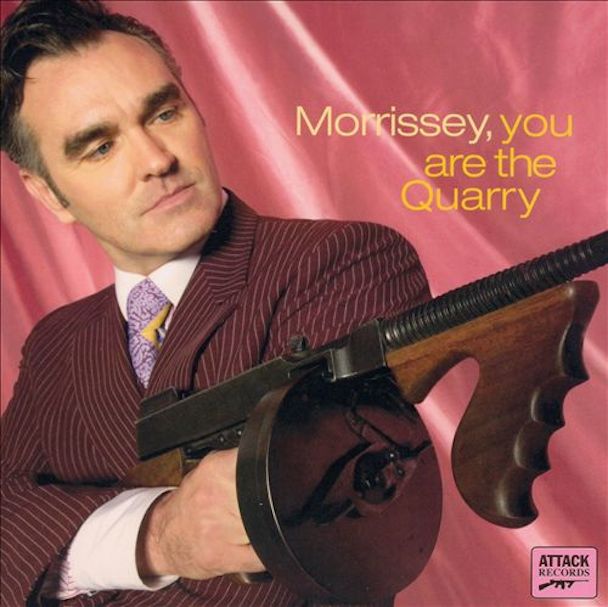

But vintage Morrissey will always have its own charm, and here it’s updated in places with a foregrounded affection. "I Like You" has the requisite reference to "fat faces," but it’s still a fine us-against-the-world tune with Orbisonian warbling, baggy sequencing and a fun-dumb chorus. Written for Nancy Sinatra (Morrissey chipped in backing vocals for her version), "Let Me Kiss You" is about as lustful as the man gets. "Close your eyes/ And think of someone you physically admire," he awkwardly beseeches, bolstered by Roger Manning’s muscular piano. "Come Back to Camden" positively tingles with its images of knees, grazing then spread. And for all its unearned familiarity, "All the Lazy Dykes" is a hypnotic slice of slo-mo, with Morrissey both finding solidarity and inviting the listener to join him.

It could get lost in the opening geopolitical combo, but You Are the Quarry is Morrissey at his most ecumenical. There had always been an inferred audience of misfits and sad sacks. Now, perhaps due to his global jaunts or just hiatus jitters, he pitched the big tent before everyone’s eyes. Sometimes it was painful (take your pick from the opener: "you know where you can shove your hamburger" or "the President is never black, female or gay/ and until that day/ you've got nothing to say to me"), sometimes it was stirring (as in "All the Lazy..."). On "Irish Blood, English Heart" -- a number three single in its first week -- he gets boringly, maddeningly centrist, shading Tories and Labour alike. But he also gets across his disgust for a flag that represents racism: an olive branch years in the delivery. And on the closer, he unites everyone around the safest target: critics. "You Know I Couldn’t Last" feints with a rock intro, but settles into a self-pitying ballad of the first order. Fluttering over the plight of new fickle fans and print mags alike, he punches into the savage refrain, then the outro. "Your royalties bring you luxuries," he sings, switching to falsetto for a fourfold "but oh -- the squalor of the mind": a Radiohead record condensed into couplet form.

Morrissey’s return was garlanded by chart successes: he reached the Top Ten with four consecutive singles for the first time since his solo debut; never before had all four singles come from the same record. It was, if Wikipedia can be believed, his only platinum record as a solo artist. The occasional pyrotechnics were gone -- "Irish Blood" was even a repurposed track from Alain Whyte’s side project, Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams -- but Moz’s pipes were in fine fettle, and the record leaned both inward and outward in the expected measure. While not a regal emergence from the wilderness, You Are the Quarry proved that its maker’s viability extended past live singalongs of two-decades-old Smiths tunes.

As befits a man who never saw a declarative he couldn’t invert, the album cover inserts a comma between his name and the title. And yet, on this, his first record in seven years, he came loaded for bear, slagging America and Britain on the first two tracks. Further on, there’s a reference to "lockjaw pop stars/thicker than pig shit": tough talk from a man whose own beautiful mug has the give of candy glass. Yes, this is Morrissey come back with Big Statements, nearly always the kiss of death unless blown by rappers or hardcore punks. A record conceptually wound around his adopted Los Angeles would have been, in theory at least, a phenomenal approach. But barring "The First of the Gang to Die" and (ugh) "All the Lazy Dykes," You Are the Quarry strode onto the stage as if its creator’s hiatus had never been.

But vintage Morrissey will always have its own charm, and here it’s updated in places with a foregrounded affection. "I Like You" has the requisite reference to "fat faces," but it’s still a fine us-against-the-world tune with Orbisonian warbling, baggy sequencing and a fun-dumb chorus. Written for Nancy Sinatra (Morrissey chipped in backing vocals for her version), "Let Me Kiss You" is about as lustful as the man gets. "Close your eyes/ And think of someone you physically admire," he awkwardly beseeches, bolstered by Roger Manning’s muscular piano. "Come Back to Camden" positively tingles with its images of knees, grazing then spread. And for all its unearned familiarity, "All the Lazy Dykes" is a hypnotic slice of slo-mo, with Morrissey both finding solidarity and inviting the listener to join him.

It could get lost in the opening geopolitical combo, but You Are the Quarry is Morrissey at his most ecumenical. There had always been an inferred audience of misfits and sad sacks. Now, perhaps due to his global jaunts or just hiatus jitters, he pitched the big tent before everyone’s eyes. Sometimes it was painful (take your pick from the opener: "you know where you can shove your hamburger" or "the President is never black, female or gay/ and until that day/ you've got nothing to say to me"), sometimes it was stirring (as in "All the Lazy..."). On "Irish Blood, English Heart" -- a number three single in its first week -- he gets boringly, maddeningly centrist, shading Tories and Labour alike. But he also gets across his disgust for a flag that represents racism: an olive branch years in the delivery. And on the closer, he unites everyone around the safest target: critics. "You Know I Couldn’t Last" feints with a rock intro, but settles into a self-pitying ballad of the first order. Fluttering over the plight of new fickle fans and print mags alike, he punches into the savage refrain, then the outro. "Your royalties bring you luxuries," he sings, switching to falsetto for a fourfold "but oh -- the squalor of the mind": a Radiohead record condensed into couplet form.

Morrissey’s return was garlanded by chart successes: he reached the Top Ten with four consecutive singles for the first time since his solo debut; never before had all four singles come from the same record. It was, if Wikipedia can be believed, his only platinum record as a solo artist. The occasional pyrotechnics were gone -- "Irish Blood" was even a repurposed track from Alain Whyte’s side project, Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams -- but Moz’s pipes were in fine fettle, and the record leaned both inward and outward in the expected measure. While not a regal emergence from the wilderness, You Are the Quarry proved that its maker’s viability extended past live singalongs of two-decades-old Smiths tunes.

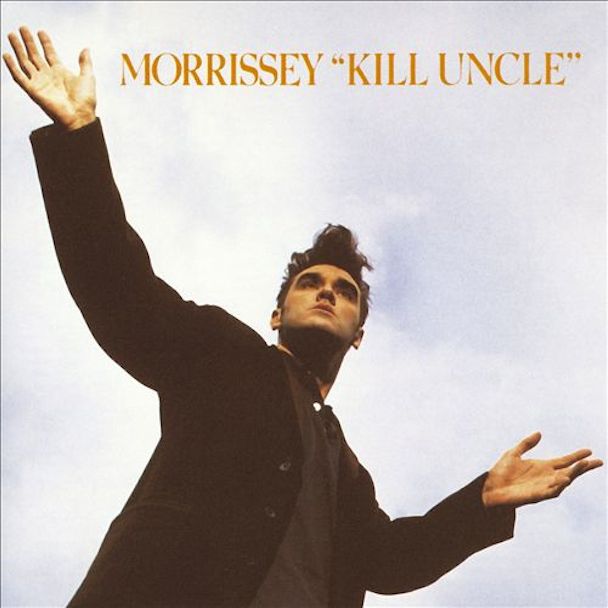

Of course, one listener’s slight perversity is another’s admirably slight perversity. Released at the dawning of the American Alt Age, Kill Uncle is, by far, Morrissey’s shortest record. It’s chock full of dinosaur drum sounds and callous musings (the aforementioned "Asian Rut" and "Mute Witness," each featuring a narrator who just wants to get the hell away). The record’s producers were Clive Langer and Alan Winstanley, a couple of New Wave-era stalwarts; the primary musician was Fairground Attraction’s Mark E. Nevin. Together, they worked up a melange of unfamiliar approaches, few of which Morrissey would pursue on later efforts. One of these is "Sing Your Life," which rolls along on "Flowers On the Wall"-style toms. Making pop look so easy, Mozz bops with the modest string touches, paying stylistic tribute to his beloved chart sirens, even contributing ebullient, swooping backing vox. "There’s a Place in Hell For Me and My Friends" trades in drab drumwork, but also Nevin’s prescient rockabilly stings.

The overall sense is of a man griping for griping’s sake: the primary accusation of the Mozz hater. The man’s never sounded so uncommitted, but then it’s entirely possible he was leery of being cornered. "The music industry has never had a vague grasp on me as an individual and it never shall," he told Creem in 1991. That sense of holding back, ever-present in his work, is especially felt here. One of two Langer compositions, "Found Found Found" crawls like prime Cure crossed with some weird English approximation of boom-bap. It’s a separation tone poem with a fantastic internal rhyme ("someone who’s worth it in this murkiness") and an oh-so-weary spoken bit. The listlessly listing "(I’m) the End of the Family Line" is a would-be childless anthem sabotaged by a distracted vocal, as if Morrissey was visualizing every inane question he’d be lobbed on the subject. Even the fake fadeout fails to shock.

His subcutural focus shifted during the making of Kill Uncle. A growing interest in rockabilly led to an introduction in the fall of 1990 to Boz Boorer, revivalist axeman for the Polecats. Within a week Boorer was recording the sinuous, trebly "Pregnant for the Last Time." With him was another rockabilly cat: Alain Whyte. Both men signed onto the Kill Uncle tour, and both men served as Morrissey’s sonic architects well into the 2000s. Their leader would receive a great measure of stability; just as importantly, he would finally have a stylistic direction all to himself.

In the years between Viva Hate and Kill Uncle, Moz revealed his interest in Polari, a subcultural slang. Used by the under- and superunderclasses of London, it was a sort of passcode in queer, maritime, criminal, and circus cultures. That last bit is especially appropriate here, as Kill Uncle sounds like a demented carnival in spots. Laughter echoes from backstage; stagehands clap along with a debauched organ. "Asian Rut" comes off as a Tom Waits chanson, as a mournful trumpet and subcontinental violin (courtesy of Nawazish Khan) escort Morrissey’s milky vocals into a world of echo. "I'm just passing through here/ On my way to somewhere civilized," he notes, and the dumb irony of the statement lets all the air out of this clunker. The anti-invasion ode "The Harsh Truth of the Camera Eye," replete with shutter SFX and rare backing vocals, reveals no more than its title; it sounds for all the world like something Matt Johnson would have discarded as too on-the-nose. "King Leer" plays like Muzak-hall; while Morrissey’s underplayed vocal is winning, it’s possible he was just recoiling from delivering hacky one-liners and a reference to a homeless Chihuahua.

Of course, one listener’s slight perversity is another’s admirably slight perversity. Released at the dawning of the American Alt Age, Kill Uncle is, by far, Morrissey’s shortest record. It’s chock full of dinosaur drum sounds and callous musings (the aforementioned "Asian Rut" and "Mute Witness," each featuring a narrator who just wants to get the hell away). The record’s producers were Clive Langer and Alan Winstanley, a couple of New Wave-era stalwarts; the primary musician was Fairground Attraction’s Mark E. Nevin. Together, they worked up a melange of unfamiliar approaches, few of which Morrissey would pursue on later efforts. One of these is "Sing Your Life," which rolls along on "Flowers On the Wall"-style toms. Making pop look so easy, Mozz bops with the modest string touches, paying stylistic tribute to his beloved chart sirens, even contributing ebullient, swooping backing vox. "There’s a Place in Hell For Me and My Friends" trades in drab drumwork, but also Nevin’s prescient rockabilly stings.

The overall sense is of a man griping for griping’s sake: the primary accusation of the Mozz hater. The man’s never sounded so uncommitted, but then it’s entirely possible he was leery of being cornered. "The music industry has never had a vague grasp on me as an individual and it never shall," he told Creem in 1991. That sense of holding back, ever-present in his work, is especially felt here. One of two Langer compositions, "Found Found Found" crawls like prime Cure crossed with some weird English approximation of boom-bap. It’s a separation tone poem with a fantastic internal rhyme ("someone who’s worth it in this murkiness") and an oh-so-weary spoken bit. The listlessly listing "(I’m) the End of the Family Line" is a would-be childless anthem sabotaged by a distracted vocal, as if Morrissey was visualizing every inane question he’d be lobbed on the subject. Even the fake fadeout fails to shock.

His subcutural focus shifted during the making of Kill Uncle. A growing interest in rockabilly led to an introduction in the fall of 1990 to Boz Boorer, revivalist axeman for the Polecats. Within a week Boorer was recording the sinuous, trebly "Pregnant for the Last Time." With him was another rockabilly cat: Alain Whyte. Both men signed onto the Kill Uncle tour, and both men served as Morrissey’s sonic architects well into the 2000s. Their leader would receive a great measure of stability; just as importantly, he would finally have a stylistic direction all to himself.

Combined with 1995’s less-than-triumphant tour with David Bowie -- in which Morrissey played for half-empty arenas -- and a singles release skein, which Morrissey considered bungled, that couldn’t place any song in the top 20, this was enough to put Mozz in a rotten mindstate. Yet Maladjusted is, on the whole, a standard Morrissey midperiod success whose reputation was perhaps scotched by one notorious track. While not as ambitious in structure as Southpaw Grammar, the now-veteran songwriting team of Alain Whyte and Boz Boorer offered reliably robust arrangements with more than a couple nods to the aging Britpop scene. Whyte dominates the record, in fact, composing seven tracks, including the festival-size anthem "Trouble Loves Me" and the defiant, galloping "Alma Matters," marred by a chintzy synth hook in the refrain.

The strongest sonic link to the previous record, "Ambitious Outsiders," is also a measure of how Morrissey had evolved as a songwriter since the Smiths. Where the maudlin "Suffer Little Children," written about the infamous Moors Murders, was sung as if from the victims -- a disembodied conscience, passing judgment on Manchester -- "Ambitious Outsiders" is a tender screed sung by a child murderer. Sure, it’s grotesque, a crawly slice of chamber gauchery that wedges in elegant pizzicato and a bit of "I Am the Walrus"-style aural chaos. But bad taste still offers its own pungent charms. Not so, sadly, for "Sorrow Will Get You in the End," a spoken-word re-prosecution of the Joyce suit that was left off the UK edition for fear of a libel suit. "You lied/ And you were believed/ By a J.P. senile and vile," Mozz intones as Boorer tries to work a clarinet without the instruction manual. One imagines the singer pacing a richly furnished study, hurling a "Bigmouth Strikes Again" twelve-inch into a malevolently crackling fireplace. It is, by far, the worst thing he’s ever recorded.

One would think that the rest of the record would sound better by comparison, but that’s not how things work. A shame, too: for every "Wide to Receive," a wilting-violet ballad with a mindboggling, first-grader-on-a-recorder solo, there’s "Ammunition," wherein Steve Lillywhite flawlessly transitions a backmasked drum part into Whyte’s squalling guitar feature. The twinkling "Alma Matters" was the lead single, and it returned Morrissey to the Top 20. An eight-country, three-stage tour followed; after, Jonny Bridgwood and Spencer Cobrin quit, creatively and physically exhausted. Having moved Maladjusted from Mercury to Island in a vain attempt to get "Sorrow Will Come For You in the End" released in his native country, Morrissey ended the tour without a label. Undaunted, he recruited a new rhythm section and embarked on two major world tours. The first, the cannily named "Oye Esteban" tour, brought him to his South American fans for the first time. And throughout his hiatus, he enjoyed life as an expat, living semi-anonymously in Los Angeles, plotting his return.

On December 11, 1996, the High Court of Justice ruled that Smiths drummer Mike Joyce was entitled to 25% of the band’s mechanical royalties. It was the culmination of seven years’ legal wrangling, during which bassist Andy Rourke -- who was once dismissed from the band due to his heroin addiction -- settled for a lump sum and 10% in perpetuity. Joyce argued that, while there was no doubting Morrissey’s and Marr’s roles as primary songwriters, the band’s royalties and concert profits were paid into a company, Smithdom Limited; as one-fourth of the band, he asserted that he had rights to one-fourth of the profits. After a well-publicized trial in which Morrissey proved alternately evasive and combative upon examination, the judge agreed. A number of the next day’s headlines gleefully quoted the judge’s opinion that Morrissey was "deviant, truculent and unreliable." Of the major papers, only the Guardian ran a photo of co-defendant Johnny Marr.

Combined with 1995’s less-than-triumphant tour with David Bowie -- in which Morrissey played for half-empty arenas -- and a singles release skein, which Morrissey considered bungled, that couldn’t place any song in the top 20, this was enough to put Mozz in a rotten mindstate. Yet Maladjusted is, on the whole, a standard Morrissey midperiod success whose reputation was perhaps scotched by one notorious track. While not as ambitious in structure as Southpaw Grammar, the now-veteran songwriting team of Alain Whyte and Boz Boorer offered reliably robust arrangements with more than a couple nods to the aging Britpop scene. Whyte dominates the record, in fact, composing seven tracks, including the festival-size anthem "Trouble Loves Me" and the defiant, galloping "Alma Matters," marred by a chintzy synth hook in the refrain.

The strongest sonic link to the previous record, "Ambitious Outsiders," is also a measure of how Morrissey had evolved as a songwriter since the Smiths. Where the maudlin "Suffer Little Children," written about the infamous Moors Murders, was sung as if from the victims -- a disembodied conscience, passing judgment on Manchester -- "Ambitious Outsiders" is a tender screed sung by a child murderer. Sure, it’s grotesque, a crawly slice of chamber gauchery that wedges in elegant pizzicato and a bit of "I Am the Walrus"-style aural chaos. But bad taste still offers its own pungent charms. Not so, sadly, for "Sorrow Will Get You in the End," a spoken-word re-prosecution of the Joyce suit that was left off the UK edition for fear of a libel suit. "You lied/ And you were believed/ By a J.P. senile and vile," Mozz intones as Boorer tries to work a clarinet without the instruction manual. One imagines the singer pacing a richly furnished study, hurling a "Bigmouth Strikes Again" twelve-inch into a malevolently crackling fireplace. It is, by far, the worst thing he’s ever recorded.

One would think that the rest of the record would sound better by comparison, but that’s not how things work. A shame, too: for every "Wide to Receive," a wilting-violet ballad with a mindboggling, first-grader-on-a-recorder solo, there’s "Ammunition," wherein Steve Lillywhite flawlessly transitions a backmasked drum part into Whyte’s squalling guitar feature. The twinkling "Alma Matters" was the lead single, and it returned Morrissey to the Top 20. An eight-country, three-stage tour followed; after, Jonny Bridgwood and Spencer Cobrin quit, creatively and physically exhausted. Having moved Maladjusted from Mercury to Island in a vain attempt to get "Sorrow Will Come For You in the End" released in his native country, Morrissey ended the tour without a label. Undaunted, he recruited a new rhythm section and embarked on two major world tours. The first, the cannily named "Oye Esteban" tour, brought him to his South American fans for the first time. And throughout his hiatus, he enjoyed life as an expat, living semi-anonymously in Los Angeles, plotting his return.

So while one might have expected the pugnacious Moz to double down on his newly claimed rock’n’roll territory, his doubling back wasn’t unsurprising. His two American tours (with Sire Records’ two Smiths compilations released in between) paid dividends: "The More You Ignore Me, The Closer I Get" was his second Modern Rock chart-topper and his only Hot 100 entry; Vauxhall was his first album to chart in the top 20, as well. On a personal note, three of his key collaborators died within a four-month period: his manager Nigel Thomas (who foresaw his charge’s American success), his primary video director Tim Broad, and Ronson. Exhausted from touring, beset by loss, he turned in what is, for many -- and Morrissey himself -- his finest solo work.

As a collection of his most direct and -- it would appear to be -- most personal lyrics, Vauxhall is a prime tour of the Mind of Moz. Gently arpeggiated, solemnly strummed, the record keeps one foot in the past at all times. There are a couple references to fathers, a gentle portrait of oblivious Britons at a war’s dawning, a track loaded with namechecks of Graham Greene characters. The wah-laden "Billy Budd" seems to obliquely reference a couple of Beatles tunes. It’s no surprise, then, that the biggest shocks come from opposite ends of the PPM. Morrissey goes sotto voce for "Lifeguard Sleeping, Girl Drowning," giving equal billing to twin clarinets."There’s no movement," he moans: "Hooray." In "Speedway," a damn chainsaw gets revved, startling the listener at least as much as the admission that "all those lies, written lies… they weren’t lies." With a wide-ranging vocal approach, Morrissey strips all potential cheek from the text, while the band bombs the ocean floor. Producer Steve Lillywhite’s recording of the drums alone would practically make this Moz’s finest closer.

Lillywhite, best known for his widescreen sheen, applied to painfully earnest acts like U2, applies a light touch to the proceedings, relying instead on the compositional skills of Boorer and Whyte. The result was a best-case for Morrissey: a well-received record that (generally) cooled the conflagration from Madstock while cementing his popularity in America, to which he moved around this time. As far as the man himself was concerned, Vauxhall and I was his high-water mark; critical and audience opinion has generally sided with him.

Music critics love two things above most. One is an artist returning to the spot of his initial successes. The other is songs about music critics. Having wrung the bygone rock flash from his new crew with the help of Mick Ronson (who died in April 1993), Morrissey settled back into the chime of his Smiths years. The fallout from Madstock would cling to his gold lame jacket for some time. Fortunately, though, his return to British performance would come only after a 43-date, two-leg North American tour. By all accounts, he was rapturously received; to America, the Union Jack was an exotic artifact, nothing more, and Morrissey was a link to a delicately attuned indie sensibility that took poor root stateside. (The legend of Morrissey’s Latino fanbase dates to this time.)

So while one might have expected the pugnacious Moz to double down on his newly claimed rock’n’roll territory, his doubling back wasn’t unsurprising. His two American tours (with Sire Records’ two Smiths compilations released in between) paid dividends: "The More You Ignore Me, The Closer I Get" was his second Modern Rock chart-topper and his only Hot 100 entry; Vauxhall was his first album to chart in the top 20, as well. On a personal note, three of his key collaborators died within a four-month period: his manager Nigel Thomas (who foresaw his charge’s American success), his primary video director Tim Broad, and Ronson. Exhausted from touring, beset by loss, he turned in what is, for many -- and Morrissey himself -- his finest solo work.

As a collection of his most direct and -- it would appear to be -- most personal lyrics, Vauxhall is a prime tour of the Mind of Moz. Gently arpeggiated, solemnly strummed, the record keeps one foot in the past at all times. There are a couple references to fathers, a gentle portrait of oblivious Britons at a war’s dawning, a track loaded with namechecks of Graham Greene characters. The wah-laden "Billy Budd" seems to obliquely reference a couple of Beatles tunes. It’s no surprise, then, that the biggest shocks come from opposite ends of the PPM. Morrissey goes sotto voce for "Lifeguard Sleeping, Girl Drowning," giving equal billing to twin clarinets."There’s no movement," he moans: "Hooray." In "Speedway," a damn chainsaw gets revved, startling the listener at least as much as the admission that "all those lies, written lies… they weren’t lies." With a wide-ranging vocal approach, Morrissey strips all potential cheek from the text, while the band bombs the ocean floor. Producer Steve Lillywhite’s recording of the drums alone would practically make this Moz’s finest closer.

Lillywhite, best known for his widescreen sheen, applied to painfully earnest acts like U2, applies a light touch to the proceedings, relying instead on the compositional skills of Boorer and Whyte. The result was a best-case for Morrissey: a well-received record that (generally) cooled the conflagration from Madstock while cementing his popularity in America, to which he moved around this time. As far as the man himself was concerned, Vauxhall and I was his high-water mark; critical and audience opinion has generally sided with him.

Honestly, it’s the smartest possible move. Now firmly in the internet age, Morrissey could be relied upon to give pullquotes that read somewhere between tetchy and tone-deaf; had this record contained more than a couple ballads, it would have delighted Vauxhall devotees while convincing everyone else that’s where he should have been left. Not that he couldn’t cast further back: "When Last I Spoke to Carol" is a fine alternate-future Smiths tune, with flamenco-style guitar and an imaginative brass arrangement tipping their hats to his Latino fanbase. Jesse Tobias shakes off the influence of his previous employers, Boz Boorer plays like he’s just been given the gig, and producer Jerry Finn pushes his charge’s voice into showstopping realms. He’ll surely release another record soon enough -- Boorer was recently quoted attesting to an "arsenal" of new songs -- and if he chooses to strike a more stately pace, he’ll have more than earned the indulgence.

Morrissey’s return to the studio did not mean a reduction in touring; he played over 90 dates apiece for both the Tour of the Tormentors and the Greatest Hits Tour. And the tourload only strengthened his resolve to rock. Lead track "Something Is Squeezing My Skull" goes for that ‘77 pace, with Morrissey making thrilling leaps during the titular phrase and ever risking foolishness with his yodel-tempo on "please don’t gimme anymore". (He comes dangerously, wonderfully close to yodeling on ace refuser "I’m OK By Myself".) The apostrophe on "Mama Lay Softly on the Riverbed" begs "Bohemian Rhapsody" comparisons, but the martial gallop and dulcimer clang puts this a stone’s throw from symphonic metal. More than any point save Southpaw Grammar, the weirder pieces cohere, held by Morrissey’s livewire vocal performance.

Honestly, it’s the smartest possible move. Now firmly in the internet age, Morrissey could be relied upon to give pullquotes that read somewhere between tetchy and tone-deaf; had this record contained more than a couple ballads, it would have delighted Vauxhall devotees while convincing everyone else that’s where he should have been left. Not that he couldn’t cast further back: "When Last I Spoke to Carol" is a fine alternate-future Smiths tune, with flamenco-style guitar and an imaginative brass arrangement tipping their hats to his Latino fanbase. Jesse Tobias shakes off the influence of his previous employers, Boz Boorer plays like he’s just been given the gig, and producer Jerry Finn pushes his charge’s voice into showstopping realms. He’ll surely release another record soon enough -- Boorer was recently quoted attesting to an "arsenal" of new songs -- and if he chooses to strike a more stately pace, he’ll have more than earned the indulgence.

Standing apart from the British rock revival, Morrissey still strolled into his modern phase looking over his shoulder. The referents, though, bookended the ‘60s: rockabilly and glam, respectively. The former came from a thoroughly turned-over band featuring the Alain Whyte/Boz Boorer ax attack; the latter, from producer and guitar luminary Mick Ronson, who had been diagnosed with cancer the year before. On Your Arsenal, Ronson provided Morrissey with form-fitting rock arrangements, and just in time, too: with the Madchester scene on the wane and Britpop just revving up, 1992 was the perfect time to head comparisons off at the pass. Johnny was busy tricking out Dusk, The The’s existential pop/rock masterpiece; PJ Harvey dropped some glammy strut into her debut LP Dry, but of course that’s not how we make comparisons. Ronson let the band swing. Guitars flash like saxophones, or hang like stormclouds. The country shuffle of "Certain People I Know" bypasses thoughts of Marr’s Nashville tuning by jumping onto Marc Bolan’s white swan. Opener "You’re Gonna Need Someone On Your Side" starts like the Sex Pistols, but barrels into the surf. Drummer Spencer Cobrin, a studio newbie, supplanted the dated stadium punch of Kill Uncle with an insistent thud. His martial tapping on "We’ll Let You Know" required Ronson to pull back on the knob for the desired effect, but Cobrin gets to bear down for the final verse.

Speaking of "We’ll Let You Know," it’s second in a triptych that raised the specter of Problematic Moz. Ronson’s guitar guidance turned "Glamorous Glue" into a tour de force: a glammy march that snaps, divebombs, and pulls a wicked face when Moz sings "we won’t vote Conservative/ because we never have". The next line, of course, is "everyone lies". The party of Thatcher had been in power, with turnout greater than 72% each time, since Morrissey fronted Slaughter & the Dogs. It’s all of a piece with his penchant for leering lacerating, but for an additional bit about looking to LA for language. Threats to the Queen’s English was an occasional interview hobbyhorse of his, and it has the effect of turning the camera 180 degrees. The windswept hooligan ballad "We’ll Let You Know" finds him one with the punters, elevating gameday rituals over more of Cobrin’s militaristic snare raps. In the midsection, mocking vox are run through the pickups; guitars flutter and shrug; it pairs well with the more narcotic moments on the Flaming Lips’ Hit to Death in the Future Head. Up until the part where Moz sings "We are the last truly British people you will ever know/ You'll never, never want to know" after distant terrace shouting, that is.

But the third track, "The National Front Disco," that was the eye of the shitstorm. It’s a decent major-key rocker that, despite some rockabilly turnarounds and Steve Jones-style licks, ends up sounding like Neil Diamond’s "America". At once sympathetic and askance, the text was still stocked with troublesome slogans. Combined with a straining, tender performance, ambiguity never stood a chance. (Although the opening reference to wind, in light of the previous track’s effects, was inspired.) Morrissey compounded matters with his late addition to the bill at Madness’s two-day comeback concert in August. Wearing a gold lame jacket unbuttoned past his navel, clutching the Union Jack as a line cook would his apron, with arty skinhead portraits framing the stage, he presented a disappointingly dissonant figure, and the skins in attendance were not pleased. He canceled the next day’s appearance, but NME had their cover photo, devoting four pages of their August 22 edition to rebuke or concern trolling, depending on your level of fandom. (It’s worth noting that in the same issue, the authors took care to differentiate Moz from "a bigoted idiot like Ice Cube".)

All this was supreme fodder for the quiff-averse (to say nothing of, you know, people horrified by the specter of nationalism). The devoted would spend years practicing saying "I don’t understand what all the fuss is about" in the mirror, and a combination of unceasing Smiths goodwill, a desperate need for interesting copy, and a years-long lawsuit led NME to lower their weapons. Morrissey would spend years walking his statements back in interviews and lyrics, but in America, where the Union Jack retained a measure of chic, Your Arsenal tripped hardly any antennae. In a peculiar way, the nationalism debate only helped him: Kill Uncle had raised the notion of irrelevance; implicit in the extensive coverage of Arsenal was the idea that Morrissey still had something to say. While in retrospect a rather safe play, the beefier backdrop provided by Boorer and Whyte set Moz on a proper stylistic course.

Britpop exhumed a far different ‘60s than the Smiths. Morrissey located Thatcher-era malaise in his childhood surroundings, extracting the humanity from human capital. The guitar bands who took up Johnny Marr’s legacy tended toward celebrations of consumerism: it’s telling that perhaps the most famous battle on the Blur v. Oasis front was a sales competition. Britpop was by and large a return of moddish swagger; where Moz paid tribute to the provincial pop singers of his adolescence, the ‘90s Union Jackers focused on an era wherein the empire was exporting pop stars and not much else. (Deliciously, Marr gave Noel Gallagher a sunburst Gibson Les Paul during the Definitely Maybe sessions. It broke when Gallagher brained a stagecrasher with it.)

Standing apart from the British rock revival, Morrissey still strolled into his modern phase looking over his shoulder. The referents, though, bookended the ‘60s: rockabilly and glam, respectively. The former came from a thoroughly turned-over band featuring the Alain Whyte/Boz Boorer ax attack; the latter, from producer and guitar luminary Mick Ronson, who had been diagnosed with cancer the year before. On Your Arsenal, Ronson provided Morrissey with form-fitting rock arrangements, and just in time, too: with the Madchester scene on the wane and Britpop just revving up, 1992 was the perfect time to head comparisons off at the pass. Johnny was busy tricking out Dusk, The The’s existential pop/rock masterpiece; PJ Harvey dropped some glammy strut into her debut LP Dry, but of course that’s not how we make comparisons. Ronson let the band swing. Guitars flash like saxophones, or hang like stormclouds. The country shuffle of "Certain People I Know" bypasses thoughts of Marr’s Nashville tuning by jumping onto Marc Bolan’s white swan. Opener "You’re Gonna Need Someone On Your Side" starts like the Sex Pistols, but barrels into the surf. Drummer Spencer Cobrin, a studio newbie, supplanted the dated stadium punch of Kill Uncle with an insistent thud. His martial tapping on "We’ll Let You Know" required Ronson to pull back on the knob for the desired effect, but Cobrin gets to bear down for the final verse.

Speaking of "We’ll Let You Know," it’s second in a triptych that raised the specter of Problematic Moz. Ronson’s guitar guidance turned "Glamorous Glue" into a tour de force: a glammy march that snaps, divebombs, and pulls a wicked face when Moz sings "we won’t vote Conservative/ because we never have". The next line, of course, is "everyone lies". The party of Thatcher had been in power, with turnout greater than 72% each time, since Morrissey fronted Slaughter & the Dogs. It’s all of a piece with his penchant for leering lacerating, but for an additional bit about looking to LA for language. Threats to the Queen’s English was an occasional interview hobbyhorse of his, and it has the effect of turning the camera 180 degrees. The windswept hooligan ballad "We’ll Let You Know" finds him one with the punters, elevating gameday rituals over more of Cobrin’s militaristic snare raps. In the midsection, mocking vox are run through the pickups; guitars flutter and shrug; it pairs well with the more narcotic moments on the Flaming Lips’ Hit to Death in the Future Head. Up until the part where Moz sings "We are the last truly British people you will ever know/ You'll never, never want to know" after distant terrace shouting, that is.

But the third track, "The National Front Disco," that was the eye of the shitstorm. It’s a decent major-key rocker that, despite some rockabilly turnarounds and Steve Jones-style licks, ends up sounding like Neil Diamond’s "America". At once sympathetic and askance, the text was still stocked with troublesome slogans. Combined with a straining, tender performance, ambiguity never stood a chance. (Although the opening reference to wind, in light of the previous track’s effects, was inspired.) Morrissey compounded matters with his late addition to the bill at Madness’s two-day comeback concert in August. Wearing a gold lame jacket unbuttoned past his navel, clutching the Union Jack as a line cook would his apron, with arty skinhead portraits framing the stage, he presented a disappointingly dissonant figure, and the skins in attendance were not pleased. He canceled the next day’s appearance, but NME had their cover photo, devoting four pages of their August 22 edition to rebuke or concern trolling, depending on your level of fandom. (It’s worth noting that in the same issue, the authors took care to differentiate Moz from "a bigoted idiot like Ice Cube".)

All this was supreme fodder for the quiff-averse (to say nothing of, you know, people horrified by the specter of nationalism). The devoted would spend years practicing saying "I don’t understand what all the fuss is about" in the mirror, and a combination of unceasing Smiths goodwill, a desperate need for interesting copy, and a years-long lawsuit led NME to lower their weapons. Morrissey would spend years walking his statements back in interviews and lyrics, but in America, where the Union Jack retained a measure of chic, Your Arsenal tripped hardly any antennae. In a peculiar way, the nationalism debate only helped him: Kill Uncle had raised the notion of irrelevance; implicit in the extensive coverage of Arsenal was the idea that Morrissey still had something to say. While in retrospect a rather safe play, the beefier backdrop provided by Boorer and Whyte set Moz on a proper stylistic course.

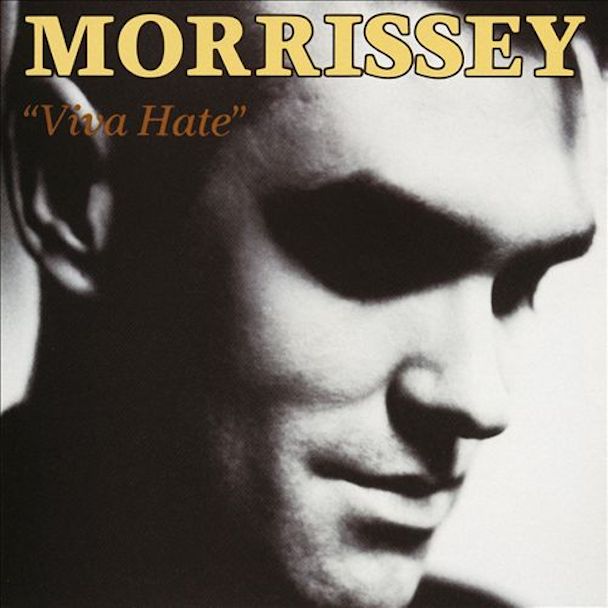

Despite the title (the record was originally pressed as Education in Reverse), you can see where the punches have been pulled. Everyone expected allusions to the Smiths. But Morrissey zagged with "Angel, Angel, Down We Go Together," written (presumably) about Marr’s propensity for outside projects. Accompanied by strings alone, he ends the track with four readings of the line "I love you more than life". A song titled "Break Up the Family" begged to be seen through the lens of dissolution. Again, though: declarations of love and a push towards hope, with complacent drum programming throughout. Ostensibly a savaging in the mold of "The Queen Is Dead," "Margaret on the Guillotine" has more in common with "Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others". It’s a dumb joke; this time, though, it lacks the temerity to be absurd. "Margaret... guillotine," he sighs, trusting that Street’s sluggish strum and Reilly’s nylon filigrees will sell the punchline. They didn’t -- and neither did the campy sound effect at the close -- but he got a police investigation for his trouble, which surely pleased him no end.

Viva Hate also contains two knockout combinations of melody and muscular guitar. "I Don’t Mind If You Forget Me" offers a dynamite backbeat, hacked-out guitar counterpoint, and some truly gonzo strangled fingertapping. "Rejection is one thing," he sighs, "but rejection from a fool is cruel": as ever, he oversees his own funeral. The evergreen "Suedehead" is perhaps Viva Hate’s closest approximation of the classic Smiths sound. Morrissey milks his questions for maximum poignancy, draping the punctuation over the full-bodied arrangement. Each iteration of the chord changes gains power. He ends the song chirping "it was a good lay" over and over, a surprising bit of bluntness matched by a low-frequency sting Street keeps punching through the mix. Wisely chosen as the lead single, it ascended to the number five position.

Viva Hate was a best-case scenario for fans. It presented Morrissey in a full variety of poses -- from balladeer to injured party to rabblerouser -- and musical contexts. It was accessible but not excessively worried over. It made room for anthems and digressions (the seven-minute Van the Man-style "Late Night, Maudlin Street," for many a highlight, to these ears a jumble of underwritten bridges). Street’s presence was reassuring, as well. He’d soon be sent packing as a response to a royalties suit, but he was an excellent link between eras. Having proved his merit as a solo concern, Morrissey retrenched as a singles artist. 1990’s Bona Drag collection ended that period, and the Waitsian Kill Uncle marked his return to larger statements.

Press speculation about the factors leading to the peculiar end of the Smiths soon gave way to speculation about how Morrissey would fare divorced from his compositional partner. Assembling a cast that included Factory godhead Vini Reilly, postpunk gadfly Andrew Paresi, and Smiths compatriot Stephen Street, Morrissey threw himself into his solo debut, scarcely a breath after Strangeways, Here We Come. Still, the sessions, produced by Street (who also served as co-writer, although Reilly claimed to have written a majority of the tracks), lasted a healthy three months. Opener "Alsatian Cousin" announced the break: a crackling landline of guitar, an exquisite pause before the thud. It’s cutting and catty, a full-length accusation ("On a groundsheet/ Under canvas/ With your tent flap/ Open wide") with doomy bass and plenty of room for the guitars to prowl. The short character sketch "Little Man, What Now?" forms a cleverly laid bridge to "Everyday Is Like Sunday," a wintry processional with Mozz’s most deliberate vocal to date. It’s an enduring example of the loving regard he could bestow on the most wretched memories. English seaside towns were skewered before and after -- Metronomy spent an entire LP applying the blade -= but on "Sunday," there’s a joy that comes from seeing your misery through.

Despite the title (the record was originally pressed as Education in Reverse), you can see where the punches have been pulled. Everyone expected allusions to the Smiths. But Morrissey zagged with "Angel, Angel, Down We Go Together," written (presumably) about Marr’s propensity for outside projects. Accompanied by strings alone, he ends the track with four readings of the line "I love you more than life". A song titled "Break Up the Family" begged to be seen through the lens of dissolution. Again, though: declarations of love and a push towards hope, with complacent drum programming throughout. Ostensibly a savaging in the mold of "The Queen Is Dead," "Margaret on the Guillotine" has more in common with "Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others". It’s a dumb joke; this time, though, it lacks the temerity to be absurd. "Margaret... guillotine," he sighs, trusting that Street’s sluggish strum and Reilly’s nylon filigrees will sell the punchline. They didn’t -- and neither did the campy sound effect at the close -- but he got a police investigation for his trouble, which surely pleased him no end.

Viva Hate also contains two knockout combinations of melody and muscular guitar. "I Don’t Mind If You Forget Me" offers a dynamite backbeat, hacked-out guitar counterpoint, and some truly gonzo strangled fingertapping. "Rejection is one thing," he sighs, "but rejection from a fool is cruel": as ever, he oversees his own funeral. The evergreen "Suedehead" is perhaps Viva Hate’s closest approximation of the classic Smiths sound. Morrissey milks his questions for maximum poignancy, draping the punctuation over the full-bodied arrangement. Each iteration of the chord changes gains power. He ends the song chirping "it was a good lay" over and over, a surprising bit of bluntness matched by a low-frequency sting Street keeps punching through the mix. Wisely chosen as the lead single, it ascended to the number five position.

Viva Hate was a best-case scenario for fans. It presented Morrissey in a full variety of poses -- from balladeer to injured party to rabblerouser -- and musical contexts. It was accessible but not excessively worried over. It made room for anthems and digressions (the seven-minute Van the Man-style "Late Night, Maudlin Street," for many a highlight, to these ears a jumble of underwritten bridges). Street’s presence was reassuring, as well. He’d soon be sent packing as a response to a royalties suit, but he was an excellent link between eras. Having proved his merit as a solo concern, Morrissey retrenched as a singles artist. 1990’s Bona Drag collection ended that period, and the Waitsian Kill Uncle marked his return to larger statements.

Southpaw Grammar is peak Morrissey. His outsider advocacy and bared-teeth grin is backed by a musical unit honed by world touring, eager to follow its chief to the ends of acceptable song length. This is the record with a two-minute drum solo in the middle and a ten-minute song at each end. There are no ballads, there is no self-conscious reaching for either his flash or jangle periods. Instead, he and the band mixed the two -- with startling portions of orchestral instrumentation and proggy experiment tossed in -- with the result being a stirring, full-throated rock record. Speaking of throats, Morrissey -- always prone to illness -- suffered from colds during the sessions, resulting in some compellingly ragged vocals in spots. It lends the record a bite akin to the glove of coverboy Kenny Lane, who went 15 rounds in Joe Brown’s successful defense of his lightweight title, prompting the champ to groan, "They should take all southpaws and drop them in the river."

"[T]he aim with Southpaw," Morrissey wrote in the liner notes to the 2009 reissue, "was to allow the musicians more room to breathe and blow like killer whales." And, er, blow they did. "Boy Racer" rides on the rails laid by Boz Boorer’s palm muting; producer Steve Lillywhite keeps Alain Whyte’s first solo back in the mix before releasing a strangled, proto-Cuomo thing. The subject of a strobe-and-Marshall loaded video, it also features this delightfully spiteful couplet: "He thinks he’s got the whole world in his hands/ Stood at the you-rye-null". "The Operation" begins with Cobrin’s startling solo (palate-cleansing, perhaps, or just completely out of place), shifts to a strutting, "London Calling"-style kiss-off, then punches into a final section that’s damn near pop-punk. Here and throughout the album, Whyte contributed backing vocals by howling into the pickup of his Bigsby guitar: a remarkable effect. Bassist Jonny Bridgwood leads off "Do Your Best and Don’t Worry," then hangs back to surge against Morrissey’s slightly negging buck-up text. Album closer "Southpaw" straddles the tonal poles of guitar, with gravedigging clusters alternating with high-end sonar pings. Whyte’s solo scrapes against the evening sky while Bridgwood works a doomy progression.

As for the man himself, he put forth perhaps his most lacerating texts. "The Teachers Are Afraid of the Pupils" is a devastating salvo at abuse in the state schools of his youth. But it’s an outlier. The bulk of the record is given over to less than sympathetic portraits of kids unaware of an brutal advancing future. Like a Holden Caulfied uninterested in -- or incapable of -- saving any others, Morrissey positively sneers at the narrowed horizons of his objects of address. The subject of "Dagenham Dave" (which could be 1. a real person 2. a reference to the possibly Mancunian man in the ‘77 Stranglers song of the same name 3. a nod at naval slang, in which Dagenham is just a tube stop away from Barking) has two girlfriends, a "mouthful of pie," and "never the need to fight or question a single thing": at least two strikes in Mozz’s scorecard. (The tune pairs excellently with its b-side, "Nobody Loves Us," with a soaring vocal that resists pity and its complementary references to pie eyes and cake-eaters.) "The Operation" shreds some soul who got pretentious and came back to tell everyone about it. "Everyone here is sick to the tattoo of you," snarls the tough-guy singer. Lest the listener share in the snark, "Reader Meets Author" is there guarding the second-track gate. Eighteen years on, the mentions of the year 2000 and people hiding behind software are entertaining, rather than barely the wrong side of prescient, but "you don’t know a thing about their lives" drives the wedge as neatly as anything the man’s written.

Southpaw Grammar was Morrissey’s sole full-length on RCA, the label that issued the Bowie records of his youth. (In 2009, Southpaw was reissued with the title’s typeface changed to resemble that of Changesbowie and Station to Station.) Just a couple years prior, he’d hinted in interviews at an imminent retirement. Now he’d landed a knockout combo: releasing his most beloved solo work and his most accomplished back to back. A February tour to promote his single "Boxers" was the first to feature Smiths songs; a series of November dates saw him opening for Bowie himself, although in more cavernous environs, the bounds of his fans’ ardor was keenly felt. (Gone were the fake bruises he wore in February.) The Smiths’ legacy was less a weight and more a relic with each passing year. Southpaw Grammar was a singular achievement: a far-ranging record that circled around well-explicated themes. It is the quintessential Morrissey document.

I’m as shocked as the rest of the Mozziverse that the man’s never recorded a Bond theme. As far as I can tell, he’s never even been approached for the task. Southpaw Grammar’s opener shows just how powerful the result could be. "The Teachers Are Afraid of the Pupils" is underpinned by a resolving string sample from the first movement of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony #5 in D, with Morrissey contributing a wearied, yet ominous performance, letting phrases hang in fog. After crawling on toms for the first half, Spencer Corbin joins the rock attack with wide-open high hat and a four-on-the-floor march. With a total thematic shift, the line "to be finished would be a relief" could serve as subtext for a Bond actor nearing the end of his term. But, of course, then the song wouldn’t be an eleven-minute epic about predatory educators receiving a just end.

Southpaw Grammar is peak Morrissey. His outsider advocacy and bared-teeth grin is backed by a musical unit honed by world touring, eager to follow its chief to the ends of acceptable song length. This is the record with a two-minute drum solo in the middle and a ten-minute song at each end. There are no ballads, there is no self-conscious reaching for either his flash or jangle periods. Instead, he and the band mixed the two -- with startling portions of orchestral instrumentation and proggy experiment tossed in -- with the result being a stirring, full-throated rock record. Speaking of throats, Morrissey -- always prone to illness -- suffered from colds during the sessions, resulting in some compellingly ragged vocals in spots. It lends the record a bite akin to the glove of coverboy Kenny Lane, who went 15 rounds in Joe Brown’s successful defense of his lightweight title, prompting the champ to groan, "They should take all southpaws and drop them in the river."

"[T]he aim with Southpaw," Morrissey wrote in the liner notes to the 2009 reissue, "was to allow the musicians more room to breathe and blow like killer whales." And, er, blow they did. "Boy Racer" rides on the rails laid by Boz Boorer’s palm muting; producer Steve Lillywhite keeps Alain Whyte’s first solo back in the mix before releasing a strangled, proto-Cuomo thing. The subject of a strobe-and-Marshall loaded video, it also features this delightfully spiteful couplet: "He thinks he’s got the whole world in his hands/ Stood at the you-rye-null". "The Operation" begins with Cobrin’s startling solo (palate-cleansing, perhaps, or just completely out of place), shifts to a strutting, "London Calling"-style kiss-off, then punches into a final section that’s damn near pop-punk. Here and throughout the album, Whyte contributed backing vocals by howling into the pickup of his Bigsby guitar: a remarkable effect. Bassist Jonny Bridgwood leads off "Do Your Best and Don’t Worry," then hangs back to surge against Morrissey’s slightly negging buck-up text. Album closer "Southpaw" straddles the tonal poles of guitar, with gravedigging clusters alternating with high-end sonar pings. Whyte’s solo scrapes against the evening sky while Bridgwood works a doomy progression.

As for the man himself, he put forth perhaps his most lacerating texts. "The Teachers Are Afraid of the Pupils" is a devastating salvo at abuse in the state schools of his youth. But it’s an outlier. The bulk of the record is given over to less than sympathetic portraits of kids unaware of an brutal advancing future. Like a Holden Caulfied uninterested in -- or incapable of -- saving any others, Morrissey positively sneers at the narrowed horizons of his objects of address. The subject of "Dagenham Dave" (which could be 1. a real person 2. a reference to the possibly Mancunian man in the ‘77 Stranglers song of the same name 3. a nod at naval slang, in which Dagenham is just a tube stop away from Barking) has two girlfriends, a "mouthful of pie," and "never the need to fight or question a single thing": at least two strikes in Mozz’s scorecard. (The tune pairs excellently with its b-side, "Nobody Loves Us," with a soaring vocal that resists pity and its complementary references to pie eyes and cake-eaters.) "The Operation" shreds some soul who got pretentious and came back to tell everyone about it. "Everyone here is sick to the tattoo of you," snarls the tough-guy singer. Lest the listener share in the snark, "Reader Meets Author" is there guarding the second-track gate. Eighteen years on, the mentions of the year 2000 and people hiding behind software are entertaining, rather than barely the wrong side of prescient, but "you don’t know a thing about their lives" drives the wedge as neatly as anything the man’s written.

Southpaw Grammar was Morrissey’s sole full-length on RCA, the label that issued the Bowie records of his youth. (In 2009, Southpaw was reissued with the title’s typeface changed to resemble that of Changesbowie and Station to Station.) Just a couple years prior, he’d hinted in interviews at an imminent retirement. Now he’d landed a knockout combo: releasing his most beloved solo work and his most accomplished back to back. A February tour to promote his single "Boxers" was the first to feature Smiths songs; a series of November dates saw him opening for Bowie himself, although in more cavernous environs, the bounds of his fans’ ardor was keenly felt. (Gone were the fake bruises he wore in February.) The Smiths’ legacy was less a weight and more a relic with each passing year. Southpaw Grammar was a singular achievement: a far-ranging record that circled around well-explicated themes. It is the quintessential Morrissey document.