In May 1994, the former Dead Kennedys frontman Jello Biafra walked into the DIY Berkeley punk venue 924 Gilman Street, and he didn't walk out again. While Biafra was watching whatever band he was watching, he got into an argument with a gang of miscreants. That argument ended in an all-out beatdown, five or six guys stomping out Biafra, seriously injuring him and sending him to the hospital. Nobody at Gilman would talk to cops, and the case remains unsolved. The reasons for the beatdown were probably standard drunk-logic things, but during the attack, those guys kept calling Biafra one thing, and that thing was "sellout." That is a goofy-as-hell epithet for a guy who helped build American DIY punk up in the early '80s and who devoted years to fighting Tipper Gore's PMRC, who never signed on with any corporate concerns. But this must've been a raw time at Gilman. A few months earlier, one band who came up at the venue had signed with Reprise and released their first major-label album, and they were well on their way toward becoming one of the most popular rock bands on the planet. The minute Green Day signed their major-label deal, the operators of Gilman Street banned them for life. This was just the way culture wars looked back then.

Honestly, by 1994, Green Day were probably too big for Gilman Street anyway. Kerplunk, the 1992 debut they released on Lookout!, had sold crazy numbers for an independent punk album and catapulted the band way past its immediate inspirations and contemporaries, the Operation Ivys and Crimpshrines and J Churches of the world. The band was always a product of its environment -- snotty dirty kids from poor, broken homes who felt most at home when they found that tiny pocket society comprised entirely of snotty, dirty kids. But they also wrote catchy songs, and you can't hold down a band who writes catchy songs. There was a Beatley tightness to Billie Joe Armstrong and Mike Dirnt's harmonies, and the sugar-rush propulsion in the band's speed was friendlier than what most of their peers could pull off. It's not that Green Day were a better punk band than their Gilman peers; that was a ridiculously fertile scene, and those early Jawbreaker records, for instance, still resonate as classics of their form. But Green Day projected in a way that those other bands didn't. And one of the remarkable things about Dookie is the way the band's sound meshed with that cleaner, more compressed major-label production style. They could make that leap, and a band like Jawbreaker, who signed and released the strong but knotty Dear You album a year later, couldn't.

Dookie is an early-'90s California punk record, but it's a great one, and it's also better-recorded than pretty much any other early-'90s California punk record. (Credit producer Rob Cavallo, who'd worked on the Purple Rain soundtrack but who found his first big-leagues production job on Dookie. He went on to work with the Goo Goo Dolls and Kid Rock and Phil Collins, and who's now the chairman of Warner Bros. During that major-label courting period, he was the only person who could talk to the members of Green Day and make them feel like human beings.) The party line, among rock critics and radio-station personalities, was that Green Day sounded like the Buzzcocks, but that wasn't right at all. (In fact, it might've just been a way for modern rock radio DJs to announce that they knew who the Buzzcocks were, something you don't often get to do when you're playing World Party and Soul Asylum records.) Green Day didn't have the Buzzcocks' all-out tinny urgency; their sound was full and warm and open and friendly; Dirnt's basslines were downright lush. The lyrics were about anxiety and boredom and sexual frustration, and they were full of sly little touches like the whore on "Basket Case" being a "he." But all that angst was delivered with vigor and humor and a sense of fun, which is what immediately set them apart when Green Day finally showed up on the radio.

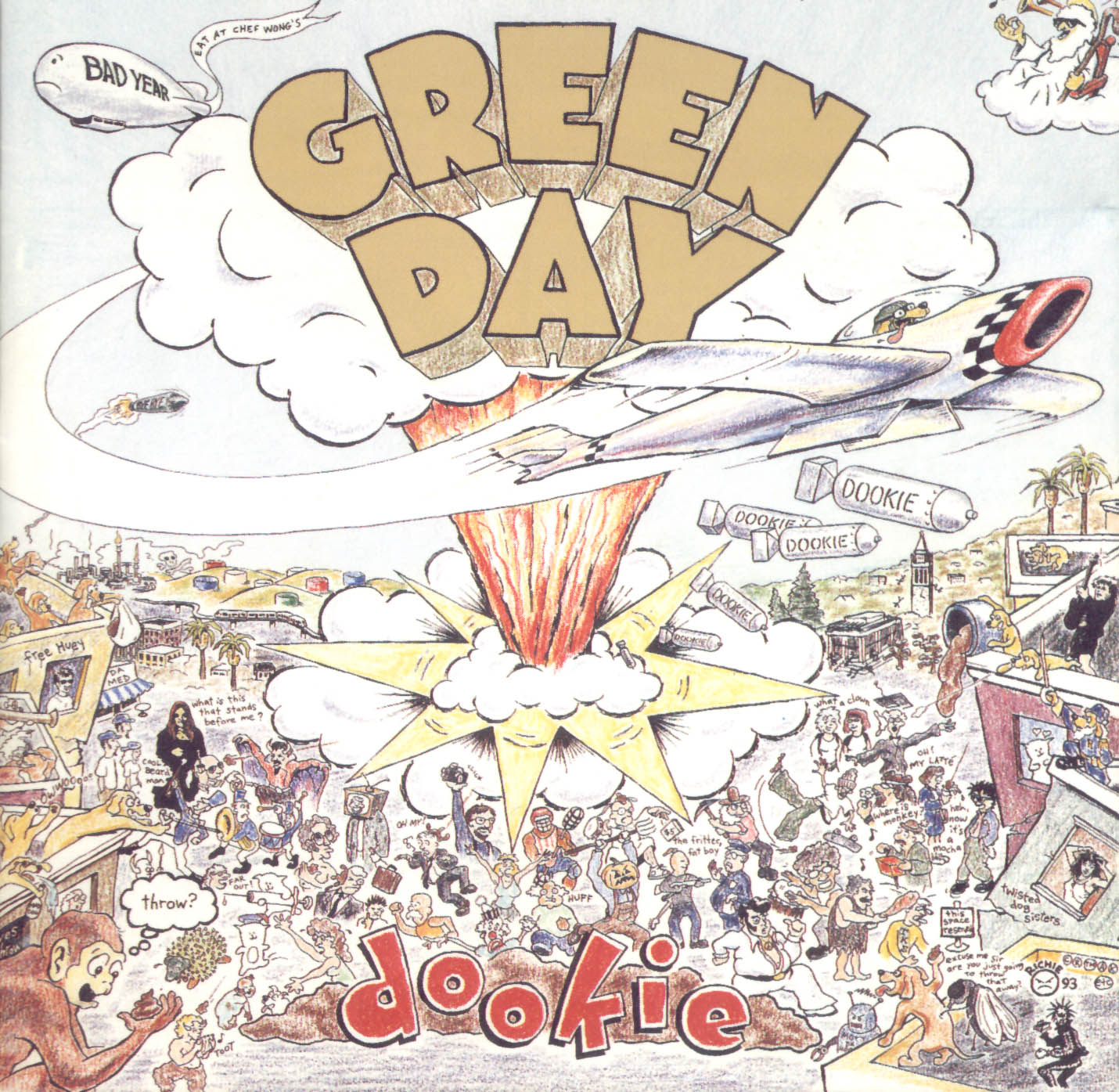

The real reason Green Day had a chance at being famous might be the most unpunk thing they'd ever done musically at that point: Dirnt's wandering-village-idiot bassline on "Longview," reportedly written and half-forgotten during an acid binge. The day after I heard that on the radio for the first time, all my eighth-grade friends spent the recess yelling bur-dur-ding-ding-ding at each other while we played handball. It certainly helped that this bassline came attached to a deeply catchy pop song with a confident build and lyrics about jerking off and smelling shit shit. Green Day's toilet-humor side, most of which came from incorrigible ADD-brat drummer Tre Cool, was dumb as fuck, but it made sense to children in a way that Eddie Vedder's high-school poetry didn't always. That's another massively important part of Green Day's success: They arrived at the exact moment when grunge started to feel oppressive. They were too busy lobbing melodic spitballs at everyone to sink into their own depression. If I'm remembering this right, "Longview" took off at radio at almost the same time that Kurt Cobain killed himself. And if the eighth-graders of the world needed a break from fuzzed-up klonopin-rock, maybe that was why. With their short songs and Pixie Stix melodies and cartoon cover art and poop-joke album title, Green Day felt like the opposite of all that. I don't know how much play they were getting on college campuses, but they were kings of my middle school.

It would be ridiculous to call Dookie the most important punk rock album of all time, but it pulled off a trick that no previous punk album had managed. It hit that level, like Journey's Infinity or Def Leppard's Hysteria or Michael Jackson's Thriller or Van Halen II, where it felt like every other song was in radio rotation at some point. It became omnipresent, a part of the air. (For the sake of argument, we're proceeding here under the assumption that Nevermind isn't a punk album, which is arguable, and that Tragic Kingdom and American Idiot also aren't, which, come on, they aren't.) It took a while for the band to sink in. Like Rage Against The Machine the year before, Green Day played first on the Lollapalooza tour main stage that summer, hitting the stage before L7 and Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds and everyone else, though it was obvious enough by the end of the summer that they were one of the biggest draws on the tour. (Fascinating trivial note: Green Day only played the second half of the tour that year. Their first-half equivalent was the motherfucking Boredoms.) And soon enough, they were absolutely entrenched. It must've been weird for the band members to hear "Welcome To Paradise," a repurposed Kerplunk song about finding a home at Gilman Street, on the radio next to Toad The Wet Sprocket, but that song, and others like it, worked as a gateway drug for kids like me to find our own Gilman Streets.

Because that's another thing. Punk rock, especially of the California popcore variety, blew the fuck up in the wake of Dookie. First up were the Offspring, whose Smash was almost as big a deal as Dookie. Those two albums led to radio love for Rancid and a resurgent Bad Religion and eventually every ska-punk band of the late '90s. They led to the Warped Tour and Mountain Dew commercials and the Tony Hawk Boom Boom HuckJam. Almost as much as the one-two punch of Nevermind and Ten, they changed things on a macro-cultural level, though maybe not for the best. But they also led to something else: To kids like me digging deeper, learning about Operation Ivy and Agent Orange and NOFX, and maybe sort of saving our lives in the process. That's something I'll get to more when I write about Let's Go and albums like that, but it ended up being huge for me and for thousands like me, and it all starts with Dookie.

Anyway. Let's watch some videos and then take this nostalgia party to the comments section.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]