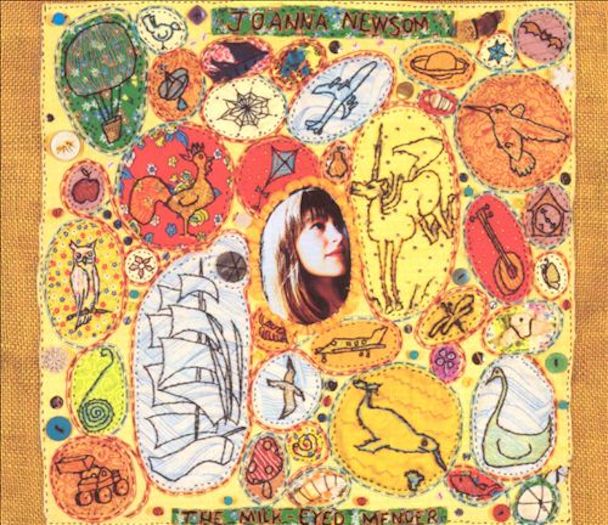

If something portends future classic status for an album, it may well be contemporary artists covering songs from the record shortly after its release. This was certainly the case with Joanna Newsom's The Milk-Eyed Mender, which will be 10 years old on Sunday. The Decemberists covered "Bridges And Balloons" for years, including a baroque reading at Terminal 5 in 2009. I saw M. Ward deliver an affected cover of"Sadie" at the Bowery Ballroom in March of 2005, while Final Fantasy gave a slovenly audience a stunning, mechanized transformation of "Peach, Plum, Pear" at a high-profile gig opening for Arcade Fire at Irving Plaza in January of 2005. Put together, these covers echo Newsom's sentiment so presciently articulated on "Sadie" -- "This is an old song, these are old blues. And this is not my tune, but it's mine to use." The lyric effectively articulates the elusive appeal of her magnificent album: She was lassoing a cosmic alchemy -- a world of blues, folk, bucolic campfire singalongs; songs of pain, the ache of memories, and ultimately, the infinite possibilities for redemption and healing. She was drawing from a collective well of sepia-tinged musical antecedents, channeled through her elegiac harp plucks, fulsome piano melodies, and a voice that poignantly conveyed a certain vulnerability that never crossed the line into tawdry sentimentality. She even chose to cover the Appalachian traditional song, "Three Little Babies," something of an anomaly on the album stylistically. The vocals on the track sound like they're emanating from a far away room, as if you have your ear pressed to the door and are struggling to discern just what's being sung, and the piano melody's oddly muted, as if it's being played into an answering machine. But Newsom sings the tears out of the track, as if it's a paean to her lost loved ones from the past, present, and future. Time and space truly are out of place here.

She was often disparaged by her detractors for her vocals, derogatorily referred to by critics as "poncy" or "whimsical." But these weren't cloying affectations. She was serving the song with her singing style, in the vein of Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, or Vashti Bunyan. Just see the brilliant, yearning opener of The Milk-Eyed Mender, "Bridges And Balloons," for a salient example. When Newsom urges, "Oh my love, it was a funny little thing, to be the ones to have seen," it's a nearly overwhelming expression of grief and loss, and her vocals, subtly rising up an octave, adroitly mirroring the gravitas of the lyrics.

Newsom's album emerged from the same fertile creative territory explored in 2004 by the likes of kindred spirits such as Devendra Banhart's Rejoicing In The Hands and Niño Rojo, CocoRosie's La Maison De Mon Rêve, Antony's then in-progress I Am A Bird Now. Basically pick any track off of The Golden Apples Of The Sun, a Banhart-curated compilation released by Arthur Magazine that served as something of a holy grail in guiding listeners to these artists for a primer. Banhart's compilation illustrated the inclusive ethos at the heart of this nascent yet fecund movement, and Newsom's music was the supreme example of this generous spirit, as she shared the stage with the likes of Banhart, Vetiver, and Antony throughout 2004 while touring The Milk-Eyed Mender. She genuinely seemed to buy into the fact that she was a part of a whole much greater than herself, and to paraphrase a quote from another traditional song, "this world was not her home, she was just passing through." But she was going to make damn sure to make an indelible imprint while she was here and vital.

Newsom told Under the Radar's Chris Tinkham in 2010, "I think there was a misconception about the songs. I got a lot of, 'Oh, these are like fairy tales, nursery rhymes,' like a lot of comments that were really coded as 'babyish' or 'youthful' or 'innocent.' And that was so not me. I don't even know how to describe what I was, but I so didn't identify with any of that, and I didn't feel my music was that. I guess, in retrospect, now, when I listen to it, I can kind of hear it more. But, at the time, I remember being initially really shocked. I knew I was doing something kind of weird, or rather that it would be perceived as kind of weird, but I didn't really identify with a lot of the words people were using to describe it."

And really, such facile descriptors do little to elucidate the divine fire Newsom was playing with on the album. Like most great records, The Milk-Eyed Mender seemingly exists impervious to outside influences, finding its own insulated corner of the world. Newsom's purview expresses unsurpassable feelings of love, quixotic wonderment, and awe at the ceaseless beauty of the small things in life. The lyrics are often entropic and frivolous, even on paper; non-sequiturs sprinkled with playful humor. But when Newsom sings them in her voice so brilliantly described by filmmaker and musician Kevin Barker in Arthur Magazine as "eight and eighty, dawn and dusk," they're revelatory reveries. This isn't hyperbole. She's that good.

Newsom would go on to grander and equally brilliant achievements (the Van Dyke Parks-produced vertiginous opus Ys, the audacious triple LP Have One On Me). Barker's documentary The Family Jams adroitly captured the milieu of the early era and Joanna Newsom's personality was on full display, whether she was performing unadorned with her harp, enthusing over meeting Linda Perhacs in California, or more gravely, getting the news that a childhood friend had died suddenly. It was disarming, affecting, and true, much like her music. The film captures a special time in Newsom and the other musicians' lives, and when a stage hand states towards the end of the documentary that this sort of thing could never happen again, he's exactly right.

A posthumous Thomas Wolfe novel was titled You Can't Go Home Again, and thankfully Newsom and the rest of these musicians never even countenanced that possibility. But they did leave us with a deep well of wonderful memories, and some of the finest albums of the '00s, of which The Milk-Eyed Mender is the crown jewel. Buy it on vinyl and revel in its resplendent beauty. It's aged marvelously.