The underground has always been hip-hop's lifeblood. Born in unofficial dance parties spread only by word of mouth, hip-hop's beginnings are rooted away from the mainstream. The cutting edge of the genre has been found under rocks, in dark corners -- something that's never more true than when you speak of the woozy beats and lexical gymnastics of MF DOOM and Madlib's Madvillainy.

The seminal collaboration between two of underground hip-hop's most respected members came about at a time when hip-hop was, in many ways, split between two camps. There were the artists that fully embraced the integration of hip-hop into pop culture. Prominent 2004 releases like Twista's Kamikaze, Talib Kweli's The Beautiful Struggle, and Kanye West's College Dropout, were crafted largely around soul samples just like those on Madvillainy, but Kanye's pop-sensible fingerprint pushed those albums toward the mainstream. Another 2004 release, Danger Mouse's Grey Album, even grafted one of rap's biggest artists ever onto one of the greatest pop groups of all time. Madvillain, though, belongs to the other category of early-aughts hip-hop artists: those that actively avoided the influence of pop. Artists like El-P, Little Brother, Deltron3030, and Cannibal Ox were making music more accustomed to the dark spaces of the underground, where the primordial ooze of hip-hop catalyzes artists that are either too unpolished for bright lights, or have no interest in them whatsoever. Ten years later we find Macklemore collecting rap awards at the Grammys. Madvillainy was, and still is, a reminder of the dirt and grit that's an integral part of the makeup of hip-hop.

MF DOOM's origin story is shadowy and unclear by design. In the late '80s Daniel Dumile (pronounced doom-ih-lay) was rapping under the name Zev Love X in a group called KMD with his brother DJ Subroc -- the chrome mask that would later turn Dumile to DOOM was nowhere to be found. Elektra Records signed KMD, but before they could glimpse the release of an actual album, DJ Subroc was hit by a car and killed. Then, Elektra dropped KMD, and the ladder to stardom was knocked over while Daniel Dumile was still clinging to the first rung. The artist soon to be known as DOOM disappeared from the hip-hop scene in '94. In later interviews he would claim that he spent the time living semi-homeless in New York, "recovering from his wounds," and preparing revenge on the industry that "so badly deformed him." In 1997 he reemerged, sporting a new identity and that foreboding mask. The super-villain, who sometimes sends impostors to perform in his stead, might not have existed if his brother had successfully crossed the Long Island Expressway in 1993.

Madlib's origin story is less murky, though he still shares DOOM's affinity for anonymity. Otis Jackson Jr. became Madlib through the venerable tradition of crate-digging. Turn-of-the-century hip-hop would not have survived without hands like Madlib's -- eager to pick through catalogue after catalogue of dusty and forgotten vinyl. From those bins, Madlib began stitching together hip-hop beats as part of a collective he called the Crate Diggas Palace. After doing production work for a few artists in the mid '90s, Madlib's new group Lootpack was signed to to a deal by Peanut Butter Wolf and his Stone's Throw Records in 1998. At Stone's Throw, Madlib began making a name for himself as an uncommon and prolific producer. His 2000 album, The Unseen, used funked-up voice modulation to create the character of Quasimoto. But just when Madlib's career seemed poised to blow up, he pulled away. He began working on a jazz-based project in which he assumed multiple alter egos; the collection of pseudonyms and characters came to be known as Yesterday's Universe. By the time DOOM and Madlib joined forces as Madvillain, each artist had his own collection of alter egos and secret identities, further obfuscating themselves from the exposing glow of the spotlight.

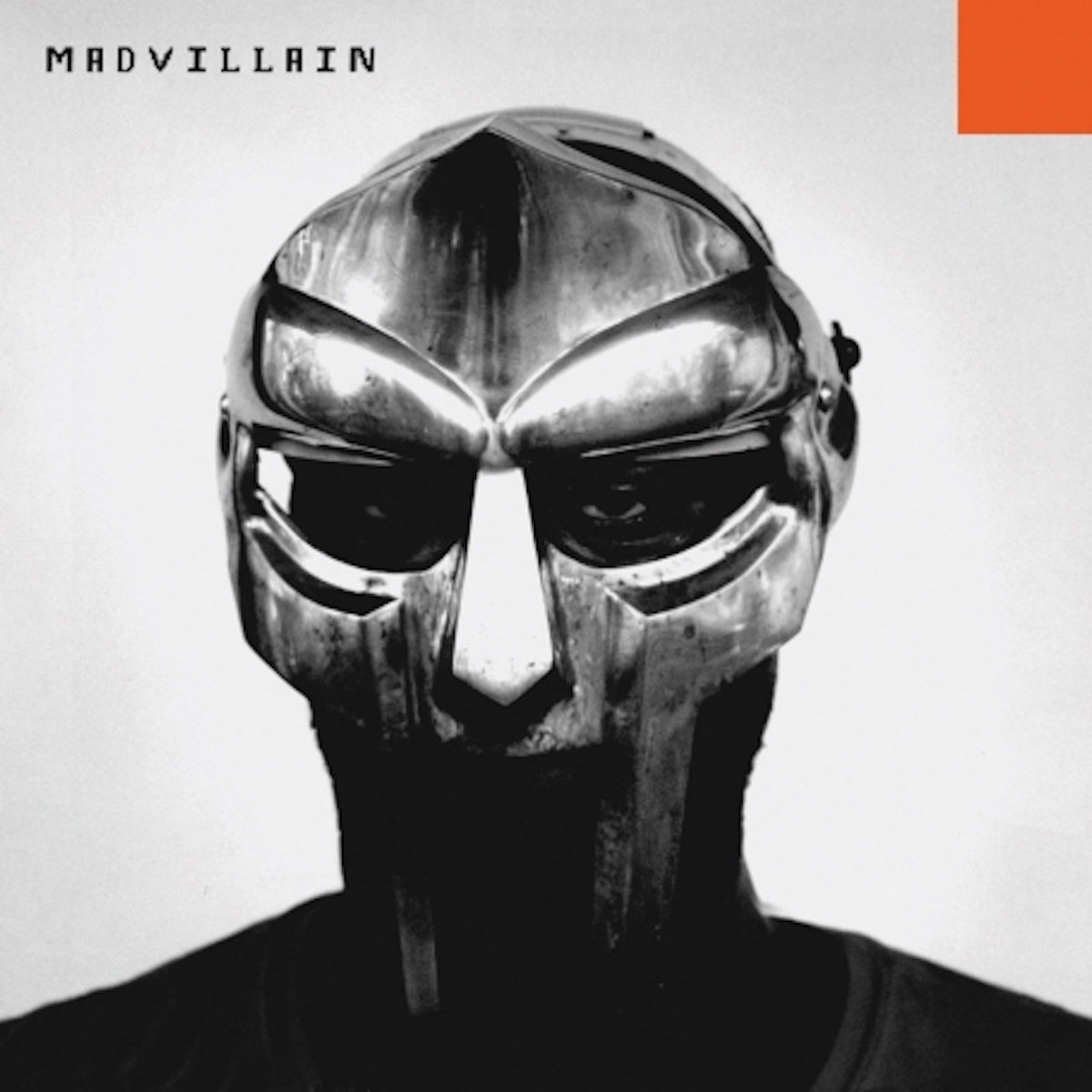

If you can locate MF DOOM, his tendency toward privacy makes him hard to work with. He takes the mask very seriously; only a select inner circle speaks to DOOM without the mask. If a stranger catches him bare-faced, he'll pull his shirt up over his head, or grab a notebook to hide behind. The cover of Madvillainy, is a photo of DOOM in his mask. The light seems to only stick to the chrome, the face of Daniel Dumile is swallowed up in its shadow. His mouth disappears completely. Only the whites of his eyes are distinct, squinted with the distrust of a super-villain. A collaborative album with such a secretive artist might have seemed like the type of thing that would never actually happen. In an interview with Egotripland, Jeff Jank, art director for Madvillainy, explained the serendipitous nature of the whole arrangement. When Madlib mentioned he'd like to work with DOOM, it just so happened that somebody at the label knew a guy who knew DOOM. "Next thing [we] knew, DOOM was out [in L.A.] too, 'doing bong hits on the roof out in the West Coast,' like he says in the first track he wrote for the album."

Jank was present for much of the recording process, spending a good chunk of time with DOOM; in fact, the Hookie & Baba line from "Bistro" is a reference to some of Jank's cartoon characters. The recording mostly took place at a house owned by Stone's Throw Records in East L.A. Madlib set up shop in the basement, getting blunted in a former bomb shelter with thick, concrete walls. Madlib worked an intense schedule, producing an impressive stream of music between two breaks a day -- to eat and smoke weed. In his interview with Egotripland, Jank detailed what happened after he picked DOOM up from his hotel in the morning:

We'd hit a liquor store around 10am. [DOOM would] write on the back porch, Madlib doing his thing downstairs in the bomb shelter… DOOM understood Madlib right off the bat. He understood where he was coming from with the music, how it connected with the records they listened to from the '60s-'90s, and Madlib's inclination to work on his own in privacy. DOOM was all for it.

In a feature for Wax Poetics the Madvillains get into the artistic processes of Madvillainy. Madlib makes his beats using a 303 sampler to draw from a portable turntable, mastering directly to a tape deck -- all of the beats on Madvillainy were made this way. It's hard to find the stems of the samples that Madlib used because he simply didn't save them. When Madlib records, he's essentially doing a live set, a type of freestyle beat-making. "You can save samples, with [an attachment for the 303] that you have to buy, but I don't go through all that hassle. [During the creation of the beats for Madvillainy] I wasn't saving 'em. I'd lay the beat straight out. To two channels." He uses this technique, which produces a two-track recording rather than a more fine-tune-able multi-track version, because it discourages other producers from "fucking my shit up. Making, I don't know, a house version of 'Curls' ... I seen what happens. I want to have my stuff out there as it's supposed to be."

Even back in 2004 the internet was the internet, so a copy of Madvillainy leaked a few months before the finished product would be released. The leaked version was clearly a rough cut, DOOM referencing the leak in "Rhinestone Cowboy," "it speaks well of the hyper base, wasn't even tweaked and it leaked into cyberspace / couldn't wait for the snipes to place / at least a track list in bold-print typeface." For the final version, DOOM would change his delivery with a lower tone and a more relaxed cadence. The new style played nicer with Madlib's bass-heavy, insouciant production. The album followed a structure that rubbed radio the wrong way: short tracks, most under 2:30, with unorthodox or non-existent hooks, and verses that required no fewer than four listens to fully grasp what DOOM was getting at. DOOM wasn't necessarily even getting at anything in particular. The album traverses the usual hip-hop tropes of drugs, women, and money -- but set against obscure, unpolished samples. The byproducts of production were left where they fell; the pop of DOOM's spit on the mic, the crackle of the record as it's fed into Madlib's 303 sampler. "America's Most Blunted" samples Steve Reich and pokes around with marijuana. In "Fancy Clown," Viktor Vaughn (one of DOOM's alter-egos) prepares to kick MF DOOM's ass for sleeping with his girl. The album is self-aware like that; DOOM repeatedly references Madlib's production, perhaps most notably when he mentions the accordion sample on "Accordion": "Slip like Freudian/ The first and last step to playing yourself like accordion." "Meat Grinder" has DOOM describing a hookup with a "subtle lisp midget" before referencing Hemingway's The Old Man And The Sea and finishing with an exasperated "…Jesus." Sometimes the tempo varies so greatly in Madlib's beats that laying a verse over them would be like trying to keep pace with a schizophrenic sprinter. On "Strange Ways," DOOM hits the brakes hard on the final couplets, anticipating the downshift in BPM as though there was no other way to deliver that particular verse. Madvillainy is less about a conceptual theme than it is about using sound to craft semi-indecipherable vignettes that are situated somewhere between the real and the mythical.

Madvillainy finally had the spotlight searching for DOOM and Madlib. Although the album received meager radio play, and only peaked at No. 179 on the Billboard 200, it got positive write-ups in the mainstream press. Even the venerable New Yorker proclaimed that "Madvillainy is why independent hip-hop isn't such a bad idea."

During the 2004 Madvillain & Jaylib Tour, DOOM and Madlib found themselves in a Canadian record store for an interview with Canada's MuchMusic. Clearly distracted by the surrounding vinyl, Madlib commented, "Hey, Canada's got good records too…," but the Sun Ra records were too expensive for him. While DOOM and Madlib dug through the crates, DOOM spoke on working with Madlib, the state of the industry, and the meaning of the mask:

[Madlib] just got me back into the whole fun part of [hip-hop]. Until then I didn't really have a partner, now I feel I found my partner… To me, from the musical aspect, hip-hop is going in a direction where almost damn near 100% it's about everything besides the music -- what you look like, the sound of your name, what you're wearing, the brand of clothing, whatever intoxicant you choose to put in your body -- everything except for what the music sounds like. The mask is really a testament to -- yo, it's not about none of that -- it's straight about the rec[ord]. It's saying that you can be any color, the mask represents everybody. Nothing else matters, brand of clothing, none of that. What matters is how you spit, and that the beats is raw.

Madlib released a tape called Madvillainy 2 in 2008. Filled with remixes of the original, the mixtape was reportedly an attempt to get DOOM excited enough to work on a true follow-up album. There have long been rumors that the project is nearly finished, but until we hear it, the second installment of Madvillainy resides in the same realm as Dr. Dre's Detox. Maybe that's exactly where it belongs: underground, in those dark hidden corners.