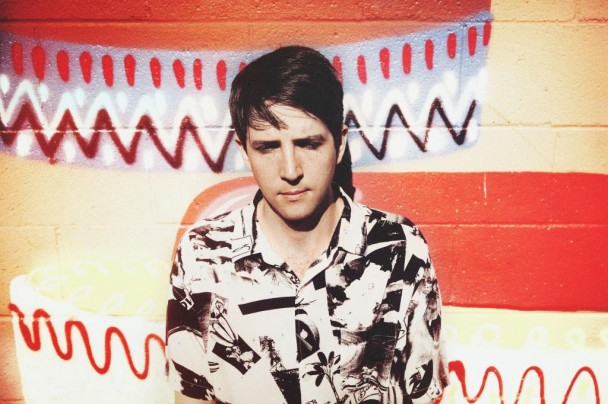

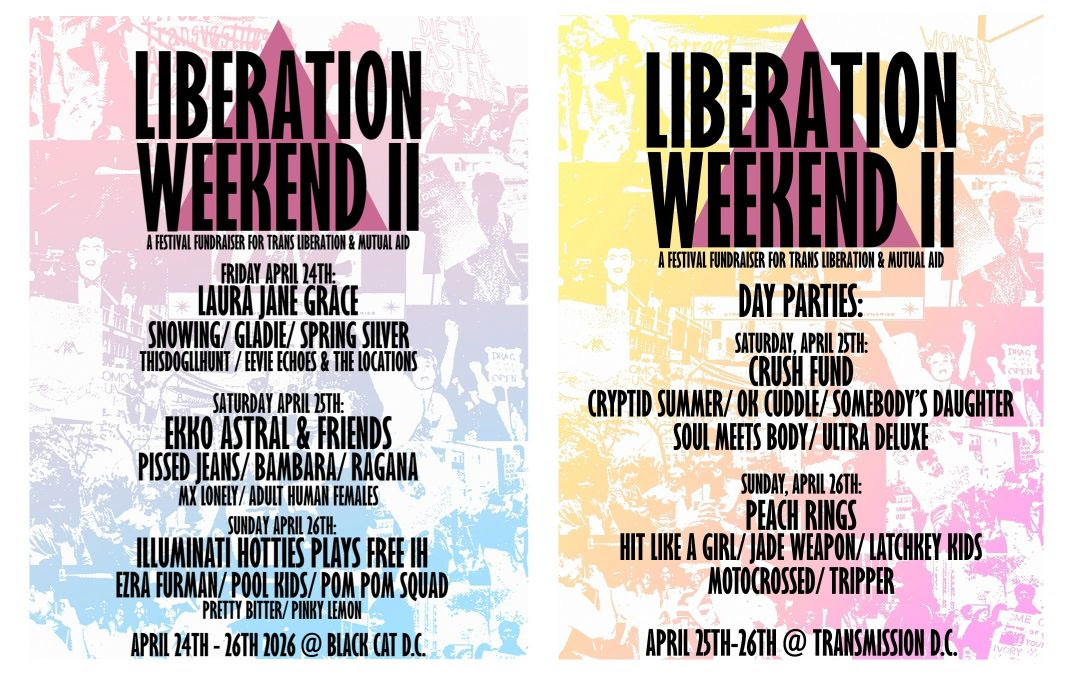

Last week Music Critic Twitter was all aflutter in response to Ted Gioia's Daily Beast essay about how music journalism has devolved into lifestyle reporting because American Idol judges don't know what a pentatonic scale is or something. Essentially, Gioia wanted more writing about the mechanics of music and less commentary on the culture surrounding it. That's a matter of preference, but Gioia alienated a lot of readers by going into grumpy gramps mode to make his point. In one of many responses to that essay, Owen Pallett, one of the guys indie rockers dial up to add orchestral flourishes to their music, penned a piece for Slate in which he expounds on the greatness of Katy Perry's "Teenage Dream" using exactly the sort of academic terminology Gioia allegedly longs for. It goes a little like this:

I have picked Katy Perry's "Teenage Dream." Because: this song's success seems to mystify all the Katy Perry haters in the world. Why did it go to No. 1? Let’s start by talking about the ingenuity of the harmonic content. This song is all about suspension—not in the voice-leading 4–3 sense, but in the emotional sense, which listeners often associate with “exhilaration,” being on the road, being on a roller coaster, travel. This sense of suspension is created simply, by denying the listener any I chords. There is not a single I chord in the song. Laymen, the I chord ("one chord") is the chord that the key is in. That is, the song is in G but there are no G-chords. Other examples of this, in hit singles: Fleetwood Mac's "Dreams" and Stardust's "Music Sounds Better With You"; almost-examples include Earth Wind and Fire's "In September" which has an I chord but only passing and in inversion; same with Coldplay's "Viva La Vida."

Informative! Pallett later references Blood Orange and Black Sabbath in the course of his argument, and he manages to fit in what might be a dig at Rick Moody, who (in another article that's been infuriating Music Critic Twitter) derided Daft Punk's "Get Lucky" as derivative pap. (Pallett: "This analysis was an easy one, because the song is straight fours and its ingenuities are easy to describe. If I were going to talk about "Get Lucky" I'd probably have to start posting score. That is a complicated song.")

Alas, some Slate commenters have disputed Pallett's analysis, citing misquoted Sabbath lyrics and misidentified key signatures. Here's one take from commenter Robert Fink:

But what do we think about the rhythmic analysis? I wish that Owen had taken a second to define "hemiola" or "cross rhythm" - it seems like the hook of the song is not really a "syncopation", but what some music theorists have called a "diatonic rhythm" -- an irregular but stable division of the metric grid. The way "Teen -Age - Dream" is sung to a 3 + 3 + 2 rhythm (the classic cross-rhythm, one half of the clave rhythm, etc., etc.) is what makes it catchy in a way that goes back to the 1950s and behind that to Africa.

Nerd out to your heart's delight at Slate, or feel free to just stay here and enjoy the KP's pop genius without pulling back the curtain. Pallett's new album In Conflict is coming 5/13 on Domino btw.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]