I met my wife at a Britpop dance night. This was January 2003 at Underground, the monthly Britpop night at the Ottobar in Baltimore, right at closing time. The last song had just played (the Jam's "Going Underground," just as it was every month), and I was in the back of the room, looking for some girl I'd been talking to earlier in the night. My future wife walked up to me and asked if I wanted to go to an after-hours party, and I think we ended up to going to three different parties before the sun came up the next morning. Baltimore is a small city, and she was just moving there, so we would've probably met each other anyway. But that particular Britpop dance night is where we did meet -- both of us slightly drunk, both sweaty from dancing like goobers, both surrounded by our perma-drunk Baltimore service-class peers (the ones who were too scared to go dance to club music at Club Choices), all dressed up like service-class Londoners from eight or so years earlier. On some level, our two kids owe their existence to the one club night where Charlatans UK and James stayed in rotation. And I don't know how many other kids owe their lives to all the various similar nights that flourished in different cities in the early '00s, but I'm betting the number is higher than you'd think.

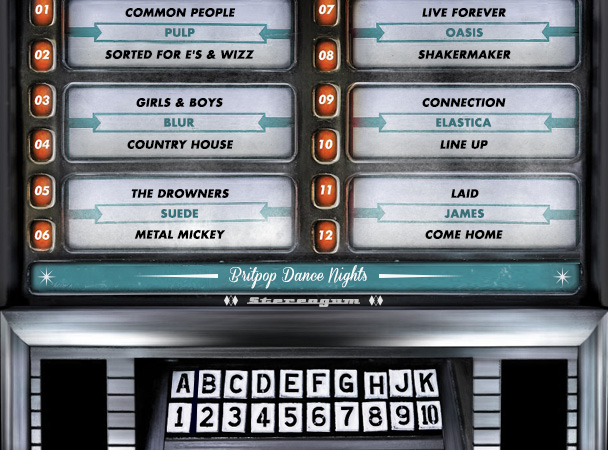

Britpop was over and done by the early '00s. Pulp were breaking up. Blur were slowly going world-music while breaking up. Oasis were well into a long, protracted decline. The many smaller bands were sliding out of relevance. The British music press was either hyping sleepy MOR bands (Starsailor, Badly Drawn Boy) or American bands that sounded vaguely British (the Strokes, the Brian Jonestown Massacre). Coldplay, basically the Four Horsemen of the Britpop Apocalypse, were maybe the biggest band in the world. And yet in America, a place where Britpop had never become anything more than a cult concern, Britpop dance nights were slowly popping up in major cities all over the place. I danced to old Stone Roses songs at Underground in Baltimore, at Mousetrap in D.C., at Tiswas in New York, at one in Philadelphia that I don't remember the name of but they had a bunch of rooms and Black Rebel Motorcycle Club played the one time I went. In Syracuse, when I was in college, I DJed at Pop Riot, an extremely short-lived Britpop night that some friends had started. I'd load a backpack full of Pulp and New Order CDs, walk to the generally fratty Planet 505, try really hard not to fuck up on the unreliable CD turntables, hope I could sneak some Destiny's Child in later in the night without clearing the floor. This was the one time I ever DJed in public, and even though I don't think we ever drew more than 40 people while I was DJing at it, I still remember the crowd-whoop the first time I played "Blue Monday" as a life highlight.

We called them "Britpop dance nights," but that really just a catchall term for "stiff white-people music." For the past few months, for the purposes of Britpop Week, the Stereogum staff has engaged in a heated and ridiculous debate of what, exactly, constitutes Britpop -- if pre-Suede stuff like the first Stone Roses album makes the cut, or Underworld's "Born Slippy," or Super Furry Animals. This was not a concern for the people who DJed Britpop dance nights. For them (us?), "Britpop" had a fluid definition. They'd play anything that even sort of applied -- two-tone ska, Daft Punk, New Order, old Depeche Mode, the Strokes, electroclash, '70s punk, Gorillaz' "Clint Eastwood," the northern soul records that the people in Britpop bands would've danced to when they were young. At Tiswas in New York, I once saw an absolutely euphoric crowd reaction to the intro from the Moldy Peaches' "Who's Got The Crack"; that was weird. In Baltimore, Laid Back's wriggly leftfield-disco jam "White Horse" was a Britpop-night anthem, as was Plastic Bertrand's dizzy Belgian punk one-off "Ça Plane Pour Moi." But then, Jet's "Are You Gonna Be My Girl?" was a floor-filler in Baltimore for a couple of dispiriting months; I don't know if we'll collectively live that one down. As the DFA dance-punk tide started to rise, that stuff would infiltrate playlists, and sometimes the bands would play the dance nights in the early part of the evening, before shit really got going. The Rapture's "House Of Jealous Lovers" got play, though maybe not as much play as Hot Hot Heat's "Bandages." If the music could've been made by people with floppy hair and too-tight black jeans, that music had a shot at getting played.

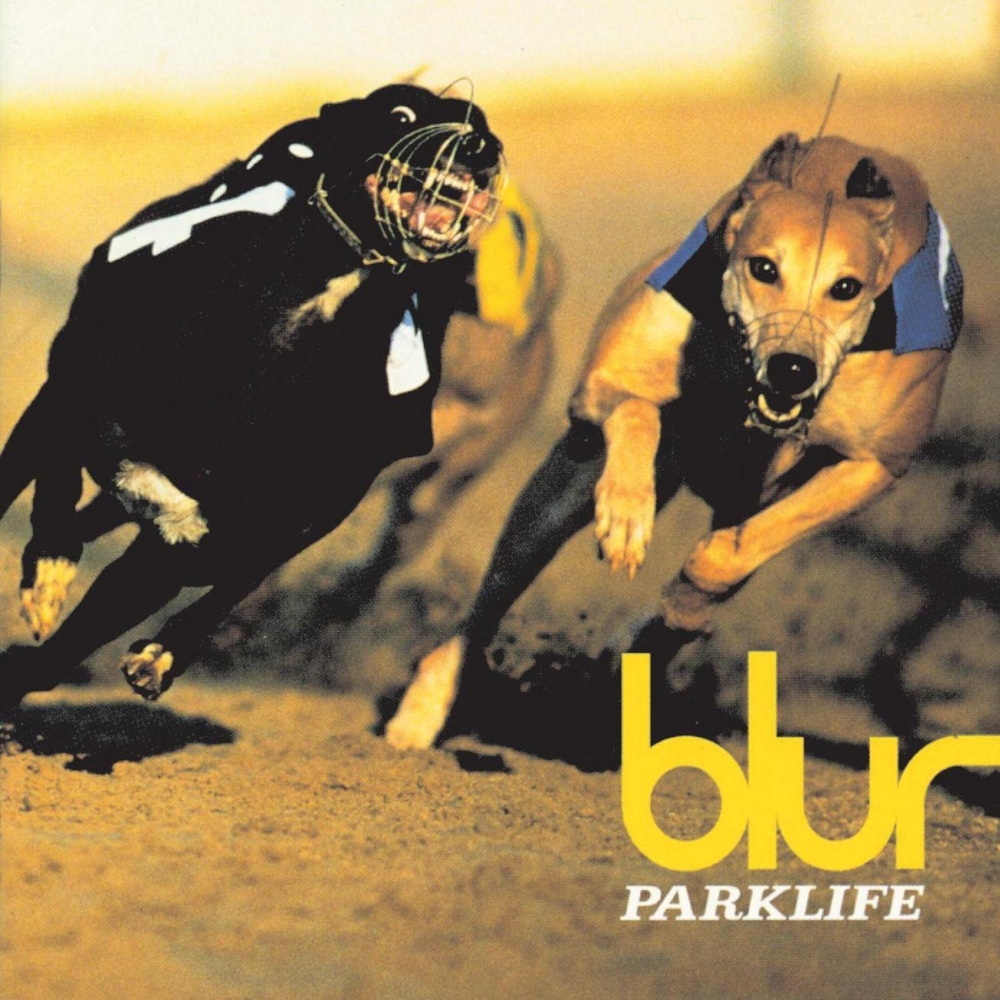

There was something regressive about the entire institution of the Britpop dance night, about white people attempting to dance to white music that was only danceable if you squinted hard when you were looking at it. (It's basically impossible to dance to the Smiths without looking like a doofus, but the Smiths might've got more Britpop-night play than any other single artist.) This was a moment when rap and pop and dance-music were cross-pollinating in some fascinating ways, when Timbaland and the Neptunes were changing the way rap radio sounded, and here we were attempting to dress like the Jam so that we could dance to old songs by the Jam. But this was the pre-Diplo era, a time when subcultures were way more stratified, when you could still get funny looks at the wrong parties for saying nice things about Jay-Z. There was a certain comfort-food aspect to these nights, especially since some of the songs that got the biggest reactions (Blur's "Girls & Boys," James's "Laid") were songs that had been all over the radio when most of the people in the room were in middle school. For underemployed indie dorks, people who had graduated college in a shitty economy and who had steam to blow off, those nights did the trick.

Another thing that drew us in: Those nights provided an extremely cheap shot of glamor into some extremely glamor-bereft lives. I don't remember paying more than $10 at the door at any of these, and at least in the non-New York cities, you could afford to drink pretty heavily on some seriously sad wages. This was right around the time H&M started opening stores in America, which meant you could dress in a busted approximation of Jarvis Cocker or Justine Frischmann for not much money. And it probably helped, too, that the Britpop haircut and the emo haircut were basically the same haircut. There was a bit of play-acting at work in this, and that whole peacocking side of it was especially prevalent at Tiswas in New York, where I remember throwing who-the-fuck-is-that-guy looks at Carlos D before I'd ever heard of Interpol. Mostly, though, this was a balling-on-a-budget situation -- a chance to go to the same clubs where you'd always go and see the same people as you always saw, dressing up just slightly more nicely than you might ordinarily. And you were way more likely to meet the person you'd marry at a Britpop night than you might be at, say, a Yo La Tengo show a week later, even if you were both at that same show. The pheromone levels at those Britpop nights were just different.

Of course, it didn't last. How could it? This whole thing was a backward-looking enterprise, and it started to feel painfully uncool once other dance nights started, dance nights where you'd hear M.I.A. or Dizzee Rascal or Slim Thug next to Björk or the Breeders. I remember hearing Hollertronix's Never Scared mix and feeling like the whole game had changed, which it had. Pretty soon, Destiny's Child wasn't something you had to sneak into the set; it was the whole point of the set. That's why I can't get mad at Diplo whenever I see him land another Blackberry commercial or Chris Brown collaboration. He was an honestly transformative figure in that little world, and the parties got more fun when they stopped ignoring rap and pop. Still, those Britpop nights probably paved the way for this new breed of club night. After all, doofs like us had to figure out that it was OK to dance somehow.

People don't really talk about Britpop nights anymore. I've never found any sort of online database of them, or any honest remembrance of what they meant to the people who'd go to them every month. There are probably still a few nights like that running somewhere in the country, but I have no idea where. I don't go out dancing anymore, and I honestly don't know where I'd start if I even wanted to. But I look with enormous fondness on those days, on those of us who tried our honest best to get dressed up and act cooler than we were. We'd missed Britpop. It had happened when we were in high school, and maybe we'd seen the Verve or Oasis at a shed somewhere, but it had passed us over. So we took it and made something else out of it. And even if what we made was just a faint echo, it was still plenty.