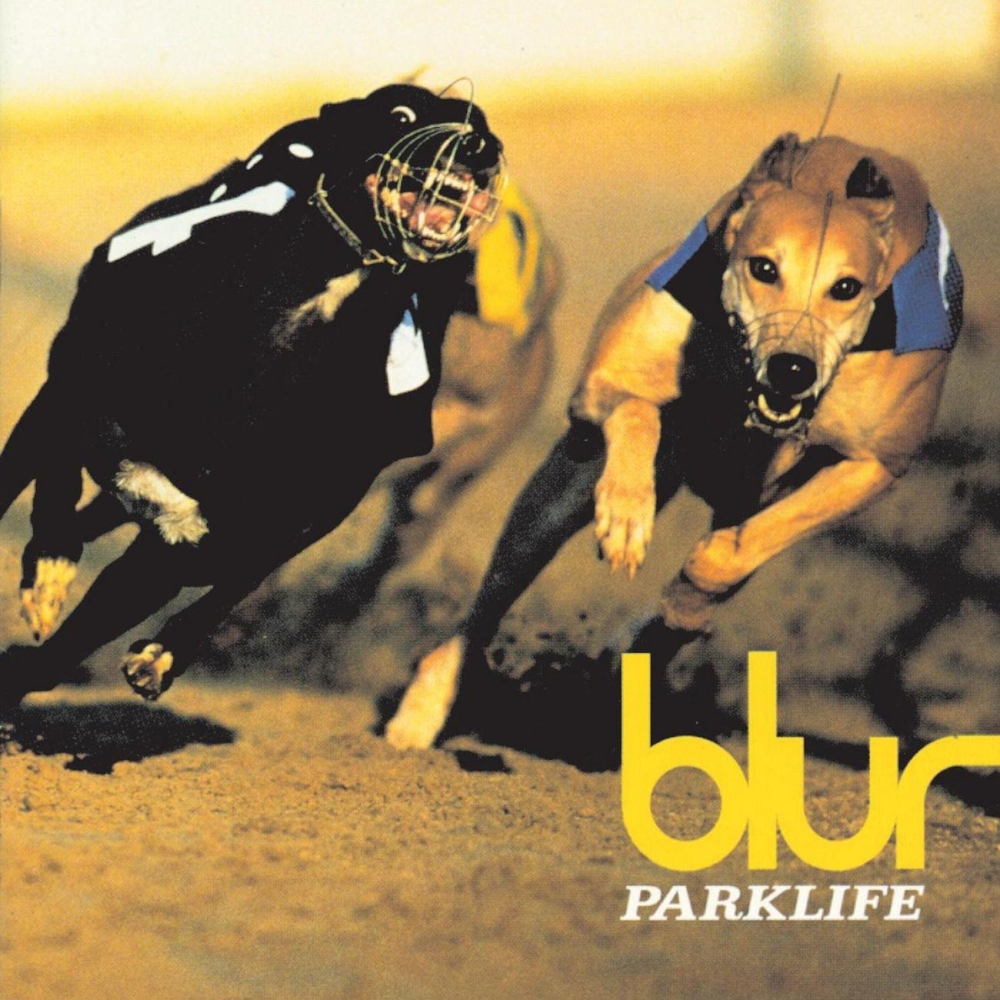

It was a profoundly strange experience to type out the headline "Parklife Turns 20." More so than the other anniversaries I've written for Stereogum, the fact that landmark Pulp, Blur, and Oasis albums are arriving at their twentieth anniversaries is something that just doesn't quite compute. Last month, I wrote about Soundgarden's Superunknown upon its own twentieth birthday, and remarked upon how this year has an odd split between American records that represent the peak and (and thus, the beginning of the end) of grunge and that first break of Alt Nation, and the records that represent the beginning of something else entirely over in Britain. Parklife still feels vital in a way that those American records do not. Superunknown and VS. and In Utero sound exactly like twenty years ago is supposed to sound. Intellectually, obviously it's easy to conceive that Britpop was indeed very much a thing of the '90s itself, and critically it's easy to understand the sounds that make it up are just as stereotypically '90s as fuzzy drop-D guitar riffs; you just have to adjust your context. Maybe this stuff has just held up remarkably well. Whatever the reason, Parklife does not sound twenty years old.

This is sort of weird to think about, but Parklife was at the time positioned as something of a comeback for Blur. After seeing some moderate success with early singles like "She's So High" and "There's No Other Way," (which hit #8 on the UK Singles Chart) Blur had departed from their more Madchester-indebted beginnings and approached what would become the Britpop sound with 1993's Modern Life Is Rubbish. That transition was a strained one. Blur may have flirted with pop success during the Leisure days, but they weren't taken seriously critically, and were seen as a ripoff of and studio cash-in on bands like Happy Mondays, the Stone Roses, and the Charlatans. As Michael wrote in his anniversary piece for Modern Life Is Rubbish last year, Blur returned from their first, by-all-accounts miserable tour of America with a frontman possessed: to dethrone bands like Suede and take the mantle as the era's eminent British band, to assert an identity of Britishness sonically and thematically. Blur's sophomore album had to change their lives and prove something. It was to be a departure from the last generation of British music Blur had at first been lumped in with, as well as a sharp rejection of the American grunge movement. Modern Life Is Rubbish achieved the latter, allowing Blur to crystalize that idiosyncratically English identity Albarn was seeking, but it didn't make them stars.

With Modern Life Is Rubbish failing to produce major singles, the making of Parklife had a make-it-or-break-it vibe to its creation, partially due to the band's precipitous financial footing at the time. It of course wound up catapulting them to superstardom, boasting four hit singles ("To The End," "End Of A Century," "Parklife," and "Girls & Boys," one of the only Blur songs aside from "Song 2" that I've ever heard in public in America). The album was massive, and depending on your allegiance and preferences it basically comes down to this, Definitely Maybe, or Different Class as the quintessential and most pivotal Britpop album. There's a reason we chose this week to do Britpop Week.

In hindsight, Parklife is the second installment in a trilogy that begins with Modern Life and ends with The Great Escape. Each of these are high up on the list of my favorite albums, period (as are Blur and 13, but I digress), and there have been different moments when each one had its time as my favorite spot amongst the three. I assume I'm in the minority here, but there's also been a lot of times where Parklife was actually my least favorite of the three. This is not the most rational critical take, and I am aware of this. Modern Life was indeed a manifesto and a confident artistic statement on its own, but Parklife refined the vision, perfected and deepened Albarn's panoramic take on a certain slice of British life and culture in the '90s. The Great Escape took it one step further -- a glossy, overblown, final act that threw the same themes and images of Parklife into a sort of pop art overdrive. That's actually why I liked it the most for so long; it was the disturbed and disturbing hangover to Parklife. (Also, it had "The Universal." Also, it had "He Thought Of Cars" and "Entertain Me.") There was nowhere else they could take this version of themselves after that, and they needed the reset button of Blur. You could likely make the argument that there was nowhere they could take this version of themselves after Parklife, really. There are strands of Britpop that go back further than 1994, and the genre splintered and mutated even into the '00s depending on how you look at it, but no matter what parameters you apply to it, Parklife remains definitive. Albarn said it all here.

There is impressive range on most of the Blur albums, but it's particularly staggering on their Britpop trilogy. Parklife wasn't my entry point into listening to Blur, but two of its songs were: "Girls & Boys" and "This Is A Low." These could not be further apart tonally or sonically. "Girls & Boys" blew my mind when I first heard it. That near-indecipherable first line that opens it, and thus opens Parklife. The way the guitars first slash in under Albarn drawling "On holiday" during the first verse and then keep scraping as Albarn sings "Love in the '90s/ is paranoid." The fact that there's a lyric that goes "Love in the '90s/ is paranoid" in the first place, and the fact that it's the first of Albarn's many proclamations about the times-they-lived-in. That hilarious and brilliant and nonsensical chorus: "Girls who are boys who like boys to be girls/ who do boys like they're girls who do girls like they're boys." I didn't know who the hell this guy was, but I wanted to hear more.

Where "Girls & Boys" starts Parklife off with a squiggly bit of dance-pop equal parts trashy and snarky, "This Is A Low" essentially ends it with what remains one of Albarn's best sad songs. And while he's wielded wit and condescension ably throughout his career, Albarn excels at a dark song: "Sing," "Resigned," "Beetlebum," "Tender" (or, you know, all of 13), Gorillaz' "El Manana," The Good, the Bad, & the Queen's "Herculean." But "This Is A Low" still stands out. Most of Parklife is jaunty and spiky and acerbically tongued, and then "This Is A Low" comes along as this entirely crushing conclusion. The power is mostly in that chorus, which is built on a melody that seems to be the exact aural embodiment of every shade of despair and loneliness available in the human condition. The importance of Graham Coxon's guitar solo(s) cannot be overestimated here, though. The way the guitar rises up out of one refrain, a gradually overwhelming tide of distortion, and then twists and echoes against itself sums up just as much anguish as Albarn's vocals. It does something truly powerful when it groans to a halt, then calls back out insistently right before the last intensified refrain comes in. It'll bring you to your knees. It might be the best moment in all of Blur's catalog.

It's a long journey from the plastic beginnings of "Girls & Boys" to the emotive "This Is A Low," with Blur touching on New Wave, punk, mod, lounge-pop, and just plain pop over the course of it all. It's a sprawling, all-encompassing thing; the originally title London probably wouldn't have felt like an overreach. The highlights within it probably depend on your proclivities. It might be my thing for New Wave, but "Trouble In The Message Centre" was always one of my favorite Blur deep cuts. "Badhead" might fool you with its introductory horn blasts, but that's another gorgeously sad tune that functions as the final chapter in Parklife's first third. Opening with an almost cartoonishly rubbery synth-bass and continuing along one of Blur's most synthetic-sounding rhythms, "London Loves" plays off the cinematic "To The End" to give Parklife its fittingly multi-faceted centerpiece.

Last month at South by Southwest, I saw Damon Albarn twice. He is a very different performer solo than with Blur -- more subdued, playing balladeer rather than frontman. Bizarrely, even in talking to people ten or fifteen years older than myself who had ostensibly been standing around waiting to see him, I found myself repeating a similar explanation: "The singer of Blur? No? He was also behind Gorillaz?" Without fail, it was the latter that people recognized. That's part of the fun of this whole Britpop Week and of looking back at a record like Parklife -- there's an evangelism streak to it, an urge to geek out about artists that are only, still, tangentially known Stateside. That makes the process of revisiting this stuff invigorating, and Parklife still stands as one of a handful of pinnacles in the whole narrative. It's a rare thing to come around to a landmark album's twentieth birthday and still feel the need to climb onto something, demand people's attention, and let them know there is a brilliant song called "This Is A Low" on a brilliant album called Parklife, and that they are missing out. Intellectually, you know it's not true, but it doesn't matter: two decades on, Parklife still has the sound of something that's just starting.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]