1994 was a big year for reclamations. Quentin Tarantino pulled John Travolta from Look Who's Talking-franchise purgatory, gave him the closest thing Pulp Fiction had to a lead role, and reignited his career. George Clinton rode high with about five billion G-funk samples of his work, and he and his P-Funk All-Stars toured with Lollapalooza, playing the main stage between the Breeders and the Beastie Boys. Most confusingly, Tony Bennett showed up at the VMAs wearing sunglasses and a Dr. Seuss hat and then duetted with Elvis Costello on his MTV Unplugged album, which inexplicably and indefensibly won the Album Of The Year Grammy shortly thereafter. In the summer of 1995, Tony Bennett was a surprise guest at the HFStival, a radio-station alt-rock festival in Washington, D.C., and I definitely smoked weed during his three-song set. I may have also crowd-surfed; I'm not sure. These were weird times, and I'm half-convinced that the finger-snapping Bennett comeback paved the way for the swing revival a couple of years later. With all those reclamation projects, even the Tony Bennett one, there was an element of honest appreciation. These people had done amazing things earlier in their lives, and it felt good to pay them a weird sort of respect. But there was also something cynical and awkward about it. These people nudged us to remember their younger, better selves, reducing themselves to the broadest elements of past personas, turning themselves into human catchphrases: Travolta prowling a stylized dancefloor like a panther, Clinton presiding over diapered bassists and smoke-billowing spaceships, Bennett winking and pointing. We appreciated all of them sincerely, but there was something cartoonish in the way we appreciated them, and something cartoonish in the way they accepted that appreciation. Which brings us to Johnny Cash.

By 1994, Cash was a country-music survivor who existed only on the fringes of the industry, playing shows on the nostalgia circuit and continuing to crank out albums for a dwindling base. Cash's stylized, self-created outlaw persona had served him well for many, many years, but mainstream country was well into its glittery Garth Brooks era, and it had little use for wizened badasses like Cash and his contemporaries. For a while, Cash's daughter Roseanne had been a bigger country-radio star than he was. That's when Cash hooked up with Rick Rubin, who, almost overnight, had gone from producing harsh, elemental rap tracks that helped change the sound of the genre to being the most California person in the entire history of the universe. This was the beginning of Rubin's bearded-guru era. He was still working with disreputable characters like Danzig and Andrew Dice Clay, but he'd also ushered the Red Hot Chili Peppers into stardom by producing Blood Sugar Sex Magik, and he'd be on to more prestigious things soon enough. In Cash, Rubin saw an unrecognized avatar of cool, an outsider figure with a rich history who could teach alt-rock-era rebellious types a few things. And American Recordings, Cash's first full-length collaboration with Rubin, is explicitly pitched as an appeal to younger listeners: Hey, kids, this guy your parents like? He's cooler than them. He's cooler than you, too.

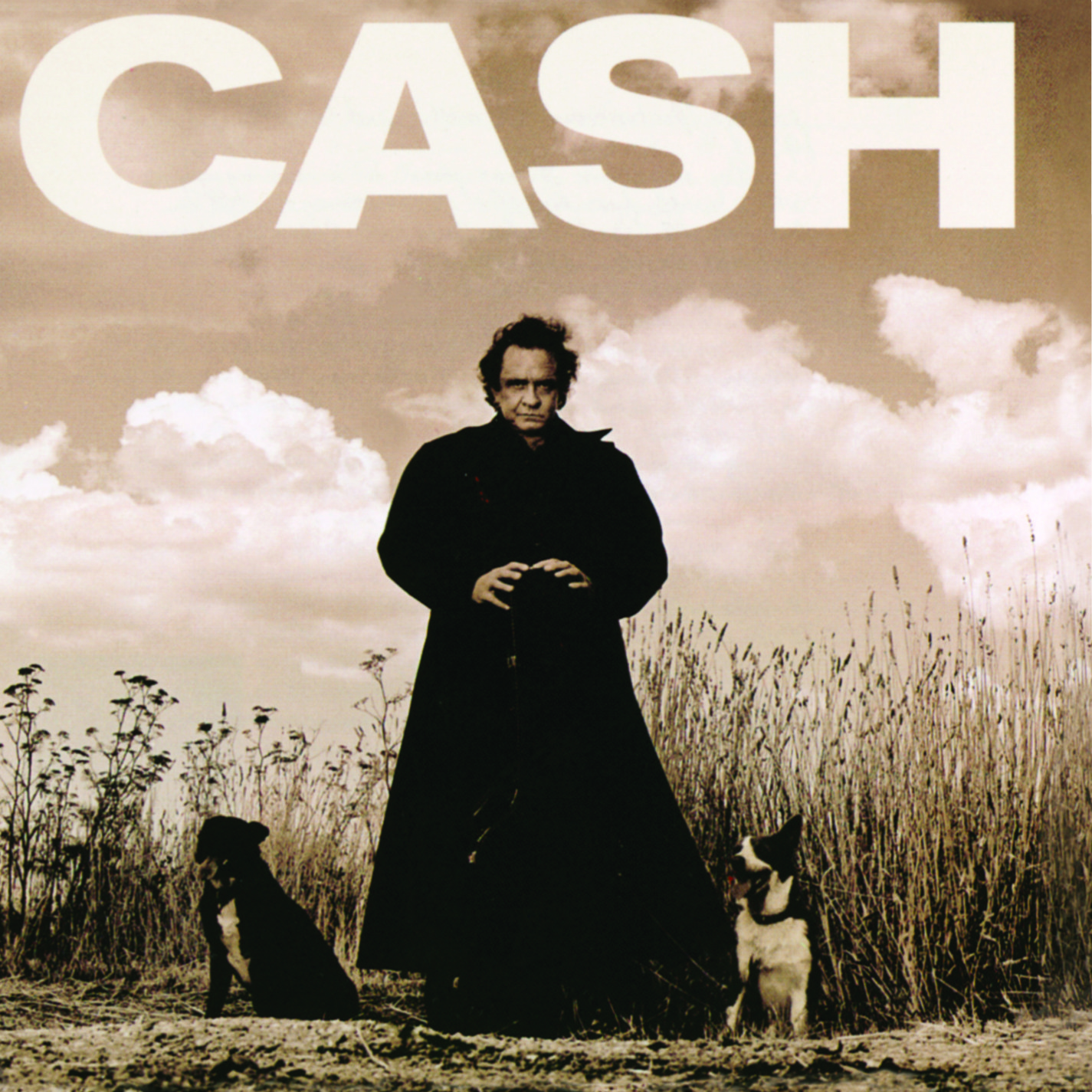

Rubin recorded American Recordings solo-acoustic-style in Cash's living room -- an approach that appealed to Cash just fine, since he'd long thought he sounded best in stripped-back environs, battling against the sorts of Nashville producers who always wanted to sweeten the mix. Cash wrote a handful of the songs on American Recordings himself, but others come from hipper sources. Rubin brought in Tom Waits and Glenn Danzig to write songs specifically for Cash, and he also got Cash to cover songs by people like Leonard Cohen and Nick Lowe, his former son-in-law. This Cash-covering-younger-folks approach would edge into self-parody on Cash's second American album, when he was taking on things like Soundgarden. But the songs on the first one were, for the most part, well-chosen and smart, and they combined to paint Cash as a booming Old God of American vision, a goth forefather with dust on his shoes and death in his eye. For Rubin, the crags in Cash's voice were as important as the tone. He recast Cash as a mythic figure, an ancestral bad man who demanded his due.

Rubin did not convey that message subtly. "Delia's Gone," the album's opening track and first single, is a gruesome and uncomfortable murder ballad that Cash had originally recorded in 1962. Rubin's message was clear: This man, on record anyway, is every bit the violent wraith that the rappers and thrash metal bands on Rubin's resume were, and they belong to the same historical continuum that he does. It's a fair point, but it's not a great song, and Rubin probably overplayed his hand by highlighting the song as much as he did. (Kate Moss was in the video!) A few years later, Wyclef did a country-rap cover of "Delia's Gone" at a Johnny Cash tribute concert, and it was the worst shit ever. And by positioning Cash as an avenging gothic figure, Rubin lost out on some of the most important parts of Cash's persona: The boisterous energy, the sly barfly's sense of humor, the Christian-man upright piety. He missed out on the beat, too; Cash's earliest recordings with the Tennessee Three backing band had a simplistic forward momentum that's entirely gone on American Recordings. And those mix-sweetening Nashville insiders often had good ideas for Cash's voice; nothing on American Recordings has the resonance of those desperate mariachi horn-trills on "Ring Of Fire" or the heartbroken swooping strings on "Sunday Morning Coming Down." The two songs that Rubin recorded at Johnny Depp's Viper Room tried to show a lighter side of Cash, but every time I hear the crowd catcalls on Cash's cover of Eddy Arnold's "Tennessee Stud," I just want to walk into that room, slap the loudmouths in the face, and tell them to listen, to stop trying to prove that they're in on it.

But if American only highlights one side of Cash's persona, it highlights an important side, and it does it well. Cash's voice was still strong when he made it, and hearing it unadorned, he sounded something like a natural wonder, like a perfectly shaped rock-formation at sunset. Cash's version of the traditional "Oh Bury Me Not" introduces the idea that he's obsessed with his own death, and that same feeling went on to animate all Cash's other American albums, which Rubin kept releasing years after Cash died. The apocalyptic-desert cliches that Danzig wrote for Cash are a bit much -- "bad luck wind been blowing at my back / I pray you don't look at me, I pray I don't look back" -- but that's sort of what's awesome about them. And the campfire-singalong presentation of "Why Me Lord" and "Down There By The Train" and Cash's version of Leonard Cohen's "Bird On A Wire" gives the songs a stark emotional intensity. That simplicity has helped the album age well; today, it sounds a hell of a lot better than what Clinton and Bennett were doing in 1994.

Cash would keep making those albums with Rubin for the rest of his life, and they stayed good. My favorite is 2002's American IV: The Man Comes Around, the last one Cash released before he died; it's both the most death-haunted and the sweetest of those albums. And those albums effectively burnished Cash's legend to the extent that he's now regarded as one of the great pillars of American music history. That's a deservedly earned legend-status, and Cash probably would've had it even if he'd never met Rubin. But does a biopic like Walk The Line happen without Rubin propping Cash up and demanding that the world look at them? I honestly don't know. Since American, we've seen a long string of aging artists who have attempted to return to relevance by dropping back-to-basics albums, and Rubin himself has produced them for people like Neil Diamond and Black Sabbath. And some of those albums are great. At a certain point, though, you have to stop looking at them as the truest representation of this artist's inner soul and start looking at them as a gimmick -- one that can be effective or not, depending on how well it's done. Looking back on American Recordings on the 20th anniversary of its release, the album invented the gimmick, and it did it well. But it was a gimmick then, just as it's a gimmick now.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]