It takes about three seconds to realize what an otherworldly album you've stumbled into. "Leaf House" begins with the sound of a digital ripcord pulling, but gravity is upside down, so the hallucinatory folk song that emerges from there keeps threatening to float away. It's anchored, though, by tribal percussion and a sense that some cosmic entity keeps hitting reset every time the wild ceremonial singalong settles into staccato skipping. These creatures -- whoever or whatever they are -- are singing about a house that is sad because its owner seems to disappear whenever anyone is at the door. Then they're engaging in a sort of twee hippie call-and-response: "Kitties!" followed by "Meoooooow." Then the song is over, but the adventure has just begun.

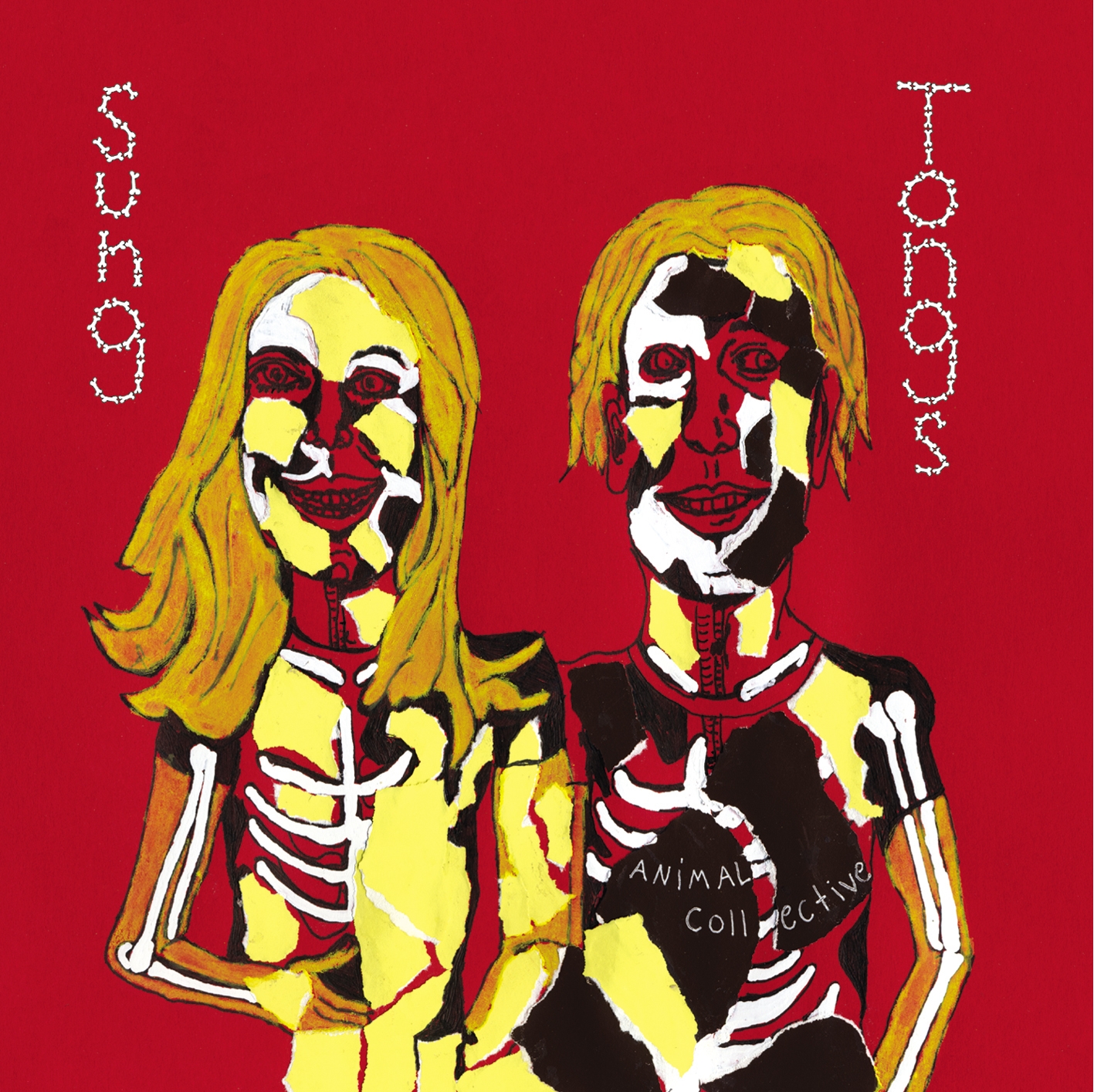

Sung Tongs, released 10 years ago tomorrow, was my introduction to Animal Collective and the beginning of a series of albums that made them one of the most influential forces in indie rock. It's no coincidence that this is also the album when the group -- in this incarnation, just Avey Tare (Dave Portner) and Panda Bear (Noah Lennox) plus producer Rusty Santos -- first steered its experimental folk/noise/psych toward something like accessibility. It was the beginning of a trend in that sense. Up until 2012's Centipede Hz, every album Animal Collective released was received by some listeners as the band's big pop gesture, the moment when they translated their utter strangeness into a sound the general public could more readily appreciate. This was the conventional wisdom about 2009's Merriweather Post Pavilion, by far the group's biggest hit to date, but you could find people hailing the approachability of 2007's Strawberry Jam and 2005's Feels too, and none of them were entirely wrong. Animal Collective did spend the better part of a decade getting poppier and poppier with every successive LP. But "pop" is a relative term, and even the version of the band that made waves with "My Girls" was still utterly, unrepentantly strange -- which just goes to show how outright fucking weird they were back when Sung Tongs came out. You wouldn't ever hear Ryan Seacrest throwing it to "Who Could Win A Rabbit," know what I mean?

That song wasn't a hit, but it packs a punch. Much of Sung Tongs comprises gorgeous acoustic strumming, gentle coos, and bizarre atmospherics -- music for zoning out, meant to be explored. "Rabbit," on the other hand, explores you. It is less than two minutes of mouth-foaming Simon & Garfunkel feral howls, The song builds from twisted human speech to aggressive strums to the sound of freewheeling pixies giddily swarming around you, begging you to loosen up. "Sometimes I can't find my good habits," they sing, as if to assure uptight doofuses like me that it's OK to let your guard down and cut loose. Elsewhere they promise us that we don't have to go to college after spending 40 seconds showing how much they've learned from the school of Brian Wilson. Even as someone who was smack in the middle of college at the time and quite liked it, I appreciated the sentiment.

Every generation needs albums to remind the squares that there's more than one way to live life. But Sung Tongs was not as revelatory for its subject matter as for propagating a completely alien sound. "Freak-folk" was becoming a talking point by the time this album came out. Devendra Banhart, Joanna Newsom, and Sufjan Stevens had just released inspired albums, each one a weird and wonderful world unto itself. None of them were as freaky as Sung Tongs, though. By peeling back much of the clatter that defined their first three albums -- no electric guitar, gentler strains of noise, mostly hand percussion -- they revealed their music's glowing core. It was unlike anything I'd ever heard; I almost would have believed you if you tried to convince me this music actually was made by woodland creatures.

Portner and Lennox hadn't calcified into distinct identities yet. They still sounded like a single unified amorphous entity here, more of a communal gathering than the array of individuals implied by the word "collective." The music they made together -- the bouncing lo-fi symphony "Winters Love," the frantic drum circle "We Tigers," the gorgeously sprawling "Visiting Friends" -- often had a mystical quality to it, as if it couldn't possibly have been recorded by twenty-first century human beings in a concrete room under red light. Occasionally, they lowered the veil to reveal how strikingly simple and real this all was. Closer "Whaddit I Done," with its Donald Duck baby-voice effect, sounds every bit like a handful of young visionaries goofing off brilliantly.

Visionary's the word, really. Few bands grasp at new possibilities in sound like these guys did over the course of their first decade together. Sung Tongs represented a change of shape, something Animal Collective would undergo many more times down the line both in terms of the group's sound and the lineup producing it. The one constant has always been that powerful creative chemistry between Portner and Lennox. They are the nucleus, and witnessing the two of them race fearlessly into the future has been one of this generation's great privileges. The fact that these same guys were responsible for the synthetic dreamscapes of Merriweather Post Pavilion just five years after this supernatural campfire music is close to unbelievable. But even if Sung Tongs hadn't been a snapshot in a breathless metamorphosis, it would stand as a masterpiece in its own right. It is Animal Collective's most compulsively listenable, intrepidly unhinged, just plain beautiful collection of music. They are the kings of the jungle, and this is their crowning achievement.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]