Talking about the dead -- especially those with tremendous, all-encompassing legacies -- is a contentious task for any music critic. The conversations around deceased artists often get trapped in discussions about their legend -- how they died, why they died, what their trajectory means in a broader context, what death does to fans -- making it impossible to dissect the art itself. This isn't necessarily a bad thing, since no art (or artist) is removed from the environments that shape and color perception of their work. It is, however, extremely confusing for those who still try to experience art as an interpersonal exchange between artist and listener.

Elliott Smith was far from anonymous in his lifetime. The power of his songs and the '90s indie underground that supported his work transmuted into tremendous interest from record labels and the pop zeitgeist. But in the wake of Smith's grisly 2003 suicide, his path has been canonized into intense legend. His struggles with addiction and suicidal despondency lace the narratives of his songs, emblematic of the pressures that consume artists when they go corporate. His legacy is wrapped in the popular emergence of indie rock culture and music, with Smith cast as the tragic hero in a war for artistic purity.

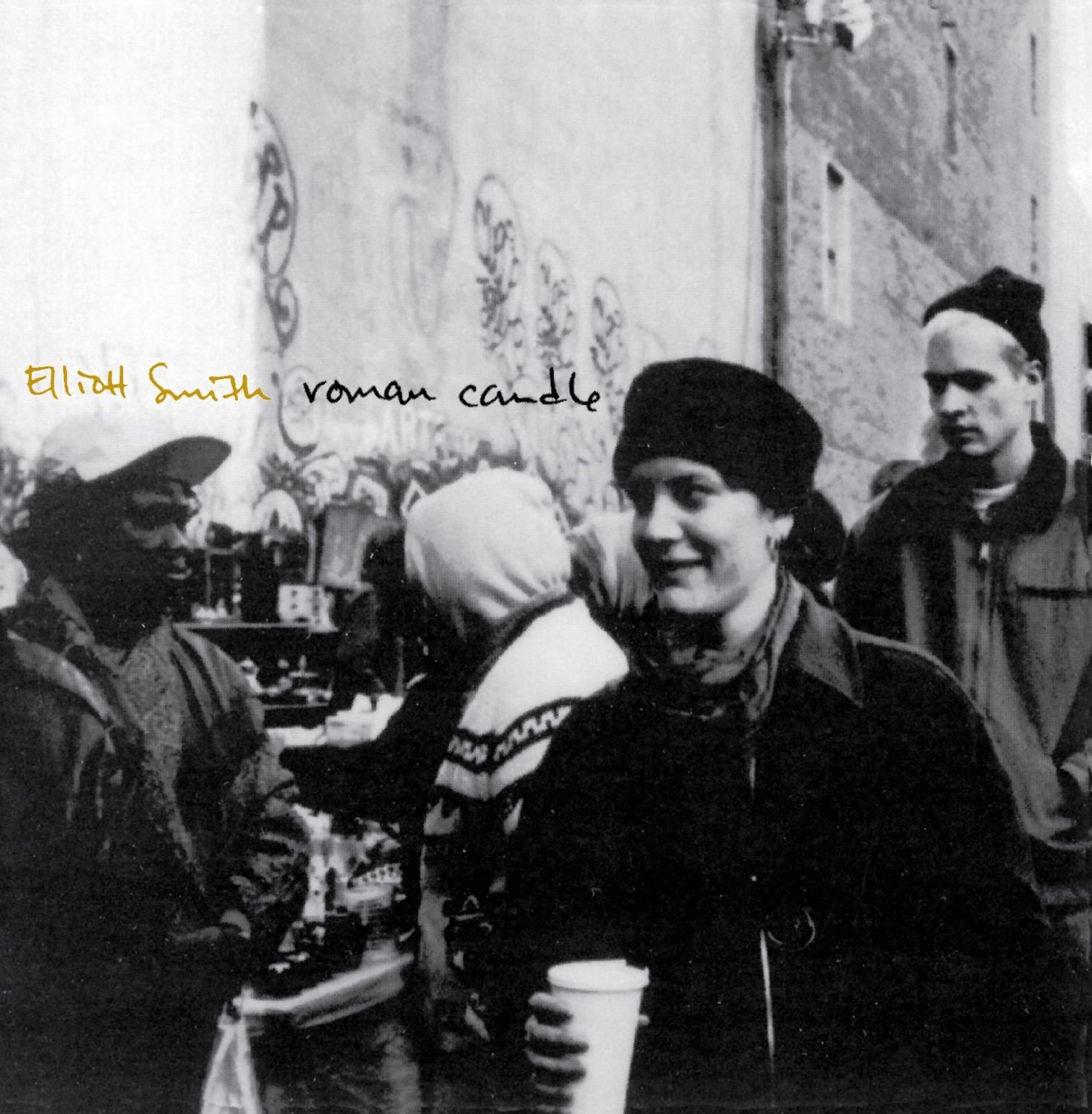

This interpretation, however tempered it might be with repeat retrospectives on Smith's life that add nuance to what could be another white-washing myth, illuminates something crucial: that Smith's music inspired rabid acclaim and devotion from critics and fans alike in his lifetime. Songs that wrenched haunting and cathartic narratives from his existence resonated with those craving emotional nakedness from their beloved artists. The seeds for everything that he would become well after his suicide (as his music is constantly rediscovered and evaluated, well into the present) were firmly planted on his 1994 debut full-length Roman Candle, which celebrates its 20th anniversary this week. This album made a silent splash that would become a full-on caterwaul in years to come.

If anything I argue here stays with you, let it be this: Context matters. Just as Smith's personal problems matter to the art he made, so does the moment in which Roman Candle existed matter to what happened at the time. Released only a few months after Kurt Cobain's suicide, the grunge bubble had officially burst. Big-budget grandiosity from integrity-minded musicians was far from over -- Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness had yet to hit shelves, after all -- but the market was open for something altogether new. The profile of recent pieces in this very series -- Rancid's Let's Go, Sunny Day Real Estate's Diary -- speaks to the diffuseness of genre expression that the alternative nation seemed ready to embrace. But in this era of supposed artistic liberation, where regional acts sparked bidding wars and your buddy's band had as much chance of getting signed as the next act on your local "Battle of the Bands" lineup, heavy riffs and distortion-driven bombast still reigned supreme. Smith, who was building a slow buzz with Portland-based folk rock band Heatmiser, didn't fit into this world at all. Despite his greasy hair and bedraggled appearance (seriously, did everybody love this look in the '90s?), Heatmiser's catchy hooks and jangly aesthetics presented Smith as transported from an alternate reality where Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin never supplanted Bob Dylan or Big Star in popularity or influence. He was not cocky or machismo-driven, nor insufferably self-conscious in the ways that other "artists" could be -- he was just soulful, withdrawn, and let his art speak for itself. It is hard to pinpoint exactly why Heatmiser never took off the way that so many other mid-'90s buzz bands did, but the fact that Roman Candle generated far more interest than any Heatmiser release is some proof that underground-looking audiences were hungry for something completely different.

That "something completely different" is manifest in Roman Candle's scrappy nine songs, recorded by Smith on a four-track in his then-girlfriend's basement and sent to Cavity Search Records with no expectation that they'd all be released as one album. Before "lo-fi" became just another production stamp for artists concerned with preserving authenticity, Roman Candle evidenced why the most unpolished recordings (even those with no hope of being polished) could be the most compelling. Audible guitar squeaks and breaths, somewhat tempered in a 2010 re-release of the album by Smith's future label Kill Rock Stars, populated songs rhythmically driven by acoustic fingerpicking or soft-strumming -- a faint gallop compared to the heavy-footed fuzzbox stomps dominating the airwaves. On what is arguably the album's heaviest song, the penultimate "Last Call," waltz-like acoustic twangs (which Smith would use to ground more expansive works on later albums) are gradually layered with increasing amounts of wandering electric guitar as Smith's signature double-tracked mumble becomes a strained snarl, harmonizing with itself while repeating "I wanted her to tell me that she would never wake me"; the result is less visceral rage and more smoldering discontent, and brutal lyrics that detail someone's descent into agency-destroying alcoholic madness (perhaps Smith's own, although this is an obviously tempting interpretation) paint a blurry image that compels listeners to enter into the story instead of expecting it to be handed to them.

This very lack of heaviness, obtuseness, or immediate sonic assault is part of why Roman Candle is ultimately a great album. Smith's later works would build upon his signature features and go in more concept-driven, compositionally-sophisticated directions. But the core of what made his music timeless -- his bizarre yet totally relatable lyrical narratives, incisive and coy in equal measure -- take center stage in this record. Smith's guitar work is generally underrated, and his picking techniques and penchant for unusual chord phrasings (more absent on Roman Candle, although some of the riffs on "Condor Ave." might drive tab-creators a little crazy) have always been more Nick Drake than Simon & Garfunkel, but he cannot be appreciated without some attention paid to the stories in his works. On the opening title track, Smith gives an understated articulation of seething rage toward some malevolent antagonist, singing "I want to hurt him, I want to give him pain/ I'm a roman candle, my head is full of flames." Again, interpreting these lyrics as diary entries and evidence of self-loathing would be easy, but they're immediately relatable to anybody who has felt seething rage toward another who has wronged them. The four songs titled "No Name" present varyingly disturbing accounts of crippling loneliness and alienation that, despite the disconcerting language of their narratives ("I'm lying here on the ground, a strip of wet concrete" and "Killing time won't stop this crime" on "#2"; "Her alone, nobody near/ What a shame, let's just not talk about it" on "#4"), take people within their stories and speak to their deepest-set insecurities. This is Smith's greatest talent in its nascent and most-direct forms on Roman Candle, a trademark that would grow stronger with every subsequent release. Half of the songs feature lamentations of waking life, with the wish of "sleep to overtake me," but this songwriter was just starting to wake up to his true potential.

It would be hard to understand Roman Candle, let alone any Elliott Smith album, without a little bit of patience. These are not songs that immediately hook every listener, and those with no predilection for sad-sack acoustic songs will avoid repeat spins. Ultimately, Roman Candle's flaws won't be disregarded or appreciated without repeat listens. But Smith was never one for making immediately brazen statements, and the result of any listener's loyalty is palpable in the legions of dedicated fans that he picked up with every small tour. Brazen, scream-out-your heart emotional release wasn't the name of Smith's game, but his poignancy inspired a catharsis made all the more powerful because it was harder fought for both listener and musician.

This is truly why Smith continues to grow in acclaim after his death. I was one of many teenagers looking for answers in his music, and no singer-songwriter captured my repeated attention quite the way that he did. When revisiting his work for this piece, I tried to understand the power he had in his lifetime by talking to colleagues and friends who vividly remembered the shows and moments that made them fans. One of these colleagues, then in the early stages of his current career as a major regional weekly's music editor, forwarded me an e-mail from Kill Rock Stars that tempered their evident grief in order to officially respond to news of his death. Another remembered starting his own career as a singer-songwriter while opening for him at a tiny dive during the mid-'90s. More recounted specific feelings they had toward certain songs. All of these accounts, mired in deeply personal and near-involuntary reactions they had towards his songs, evidence the legend that was being built even before he died. It's undeniable in its influence today and had clear roots in his lifetime.

So yeah, Roman Candle might not be the most memorable Elliott Smith album. It might not even be the best (you guys can fight that out in the comments). But if you care at all about what made this raggedy kid the transcendent enigma that he remains, Roman Candle is worth a fair amount of your attention.