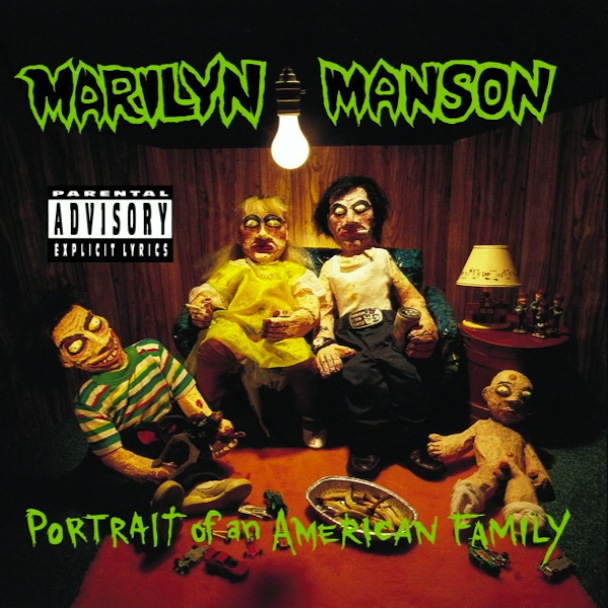

Self-indulgent storytime: The first and only time I ever did acid, I was in ninth grade, and I stayed up all night at a friend's house even though I had a basketball game the next day. Everything was going pretty well until we threw on Marilyn Manson's debut album Portrait Of An American Family, which had come out earlier that year and which turns 20 tomorrow. This was not a good idea. But listening to Portrait is just what we did that year. It's what just about all my friends did. We yelled its choruses at each other across lunch tables. We yelled its samples, the ones we didn't yet recognize as being from John Waters movies or the Twin Peaks pilot. There was a period of months where I listened to Portrait at least once, every single day. But back to the acid trip: There's a moment, near the end of final track "Misery Machine," where the music stops and these plinking noises come in and you hear all these deep voices rumble, "His horn went beep, beep, beep." I don't know why, but those voices immediately made me think of Killer Klowns From Outer Space, and that was it for me. I was done. It wasn't like I thought the clowns were in the room with me; I just couldn't stop thinking about them: "Dude, it's like greasy killer clowns, sitting around a fire, staring at me. Your light fixture kind of looks like one." My friend still makes fun of me for it. I fouled out of the next day's game, possibly in the first half, possibly without scoring.

I get the feeling that Marilyn Manson would enjoy this story. Scaring ninth-graders on acid was sort of the point of Marilyn Manson -- or it was one of them, anyway. The main point was probably to scare those kids' parents, the ones who didn't realize the kids were dropping acid in the first place. Manson's associate Trent Reznor was a target of massive parental fears during the early '90s, but Reznor wasn't a transgressive taboo-busting type; he was a sincere and emotionally intense singer-songwriter who cussed sometimes. But Manson was what parents thought they saw in Reznor. Portrait opens with Manson reciting the creepy tunnel monologue from Charlie And The Chocolate Factory, going all over-the-top hammy with it, screaming the end and throwing on all these spooky sound-effects, the type you'd blast from your front porch on Halloween. The poem was already a chilling piece of work, but Manson needed to make it more obviously scary, to eliminate even the slightest ghost of subtlety from it. Throughout Portrait, he pulls that trick over and over: Demented circus music and Charles Manson samples on "My Monkey," groaning that what he wants is just your children on "Organ Grinder." "Lunchbox" is about using a metal lunchbox to fight off your bullies, but I always thought it was a pre-Columbine story about keeping a gun in your lunchbox at school. It just made more sense, given everything else that was happening on the album.

Listening to Portrait today, I can't believe how seriously I took all this, that I didn't realize how fundamentally silly the album is. It's a well-produced grossout horror movie, a self-conscious dismantling of the '50s-style cultural morality that had mostly disappeared from mass culture by the early '90s anyway. (My working theory: when you consider Andrew "Dice" Clay and N.W.A and GN'R Lies and Total Recall and peak Bret Easton Ellis, American popular culture probably hit its crassness peak in 1989 or 1990, making Manson actually late to the party.) Portrait has not aged terribly well; today, it's a sharp and well-produced rock record with some strong riffs and a singer who seems determined to sabotage all his own songs by refusing to dial back the theatrical gurgle-growling for any reason. Reznor co-produced the album at a period when he was near king-of-the-world status, and the enormity of its guitar and drum sounds is still evident. But the songs and sentiments are a bit undercooked, and the constant samples and noises just clutter up the mix when a little empty space might've worked wonders.

But quibbles aside, those of us where were in ninth grade approached this thing with wide-eyed wonder: "Did you hear what he said? He's the god of fuck!" When Manson opened for Nine Inch Nails on their Downward Spiral arena tour, the rumors were heavy in the lunchroom the next day. I heard, more than once, that he and his bandmates were fucking each other up the ass with dildos, and it seemed plausible enough. In fact, I'm fairly certain that no '90s rock star was the subject of as many Rod Stewart stomach-pump-type urban legends as Manson was. It seemed reasonable enough to believe that he'd played Paul on The Wonder Years, or that he'd had ribs removed so that he could suck his own dick. With Portrait, he'd already established himself as an absolute fringe-dweller, a transgressive figurehead, the type of shadowy figure who captures kids' imaginations. And while he didn't really make a popular dent until his cover of Eurythmics' "Sweet Dreams" a year later, Portrait laid the foundation for that persona. It made anything seem possible. Metal had gone into the red zone with shock-value tactics before; it was a big part of what Cannibal Corpse did. Industrial music had pushed even further with it; Lords Of Acid and My Life With The Thrill Kill Kult had made careers of it. But none of them had translated that willful shock appeal to something bigger; none had made it resonate the way Manson did.

What still resonates about Manson isn't really his music, though 1998's Mechanical Animals still stands as a pretty incredible album. Manson was a culture-war agitator for our side, someone willing to jar and frighten the fuck out of the power structures that seemed there to keep teenagers in their place. His whole thing was a violent, overblown rejection of vast forces of oppression and control, and his tactics made him a target, both of mass-culture disdain (especially after Columbine) and of superior alt-culture snark (especially after that Onion article). All that was by design. He put himself out there to take those attacks. And on some level, he's a saint for that. Simply by existing, by moving the baseline, he made lives easier for hundreds of thousands of teenagers. That, rather than "Cake And Sodomy," is his legacy. Now, let's watch some videos.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]