Of all the bands that emerged from the British post-punk scene, XTC has been one of the hardest to pin down. You could peg them as an '80s dinosaur whose most recognizable tracks pop up on cut-rate compilations of new wave or classic alternative rock. Or they could slot into an adult alternative playlist, to be heard between semi-hits by Natalie Merchant and Suzanne Vega on a Pandora playlist. Or they could simply be relegated to the bargain bin of your local used CD shop, copies of their later albums collecting dust next to a dozen copies of R.E.M.'s Monster.

All of those categorizations are actually dead on. The ever-evolving group had its biggest successes in the '80s with driving, off-kilter pop songs that made hay of socio-political critiques and Beatles-like guitar hooks, and as they moved into the '90s, they were beloved by the post-collegiate crowd that didn't cotton to mainstream radio but was also turned off by what the post-Nirvana or Lollapalooza worlds had to offer. And as the band reached its autumn years, critical and commercial interest waned almost entirely -- particularly here in the States -- leaving their last two albums to be virtually ignored by the record-buying universe.

Yet looking at XTC through any one of those lenses is terribly myopic. The group, which started in Swindon, England back in 1976, has gone through one of the most fascinating career trajectories right up until their dissolution in 2000. They evolved from amphetamine-fueled imps to a sturdy modern rock group to psychedelia's second cousins to a kind of amalgam that kept an eye on each of these musical stopping points. And through it all, the band's two preternaturally gifted songwriters, guitarist/vocalist Andy Partridge and bassist/vocalist Colin Moulding, created work that only got deeper, more thoughtful, and more complex.

For all their good works, XTC have long been beset by drama, which hampered their chances at achieving mass recognition. Some of it was self-inflicted, born of Partridge's inflated ego and inherent stubbornness. Some of it was due to the shady business dealings of a former manager and mishandling by their longtime label, Virgin Records. Add to that the fact that the band stopped touring in 1982, with Partridge claiming crippling stage fright, and XTC was doomed to the cut-out bin of musical history.

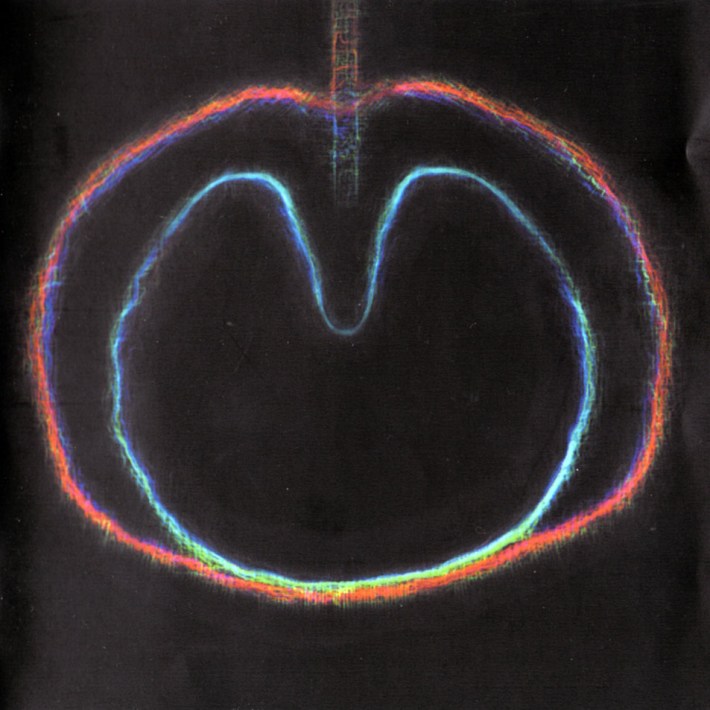

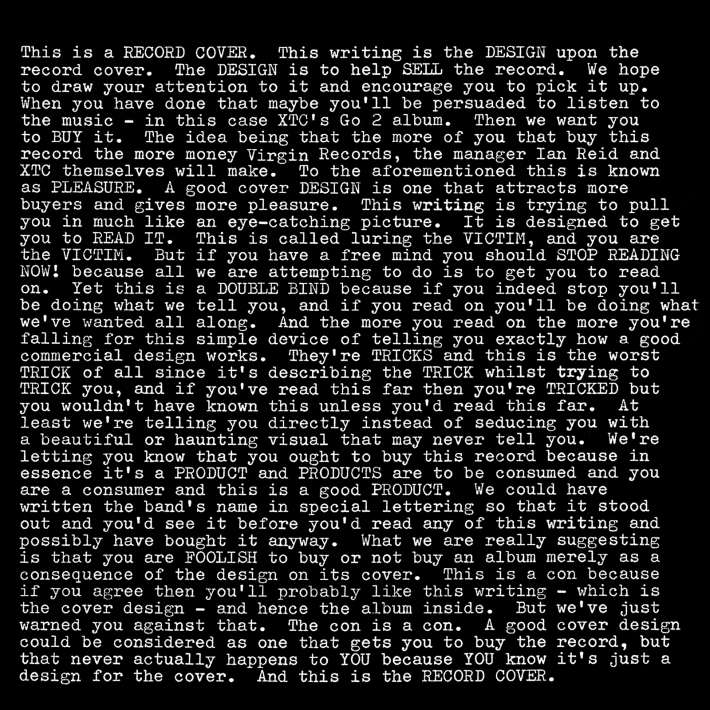

In the darker, dustier corners of the pop universe, where folks like me reside poring over the sleeve notes of Go 2 and making regular visits to the exhaustive fan site Chalkhills, these gents will remain titans of literate, craftsmanlike music that ripens with age. Yet, even as a fan, I'm not blind to the moments where their ideas or execution fell flat. But their failures tend to be fascinating ones worth discussing. I hope you'll join in that conversation with me.

What an unfortunate note to end a career on.

Of course, at the time of Wasp Star's recording and release, it wasn't entirely clear that this would be the last XTC album. This was the band making good on a promise to release two successive and complementary full-lengths, this being the electrified counterpart to Apple Venus Volume 1, released a year earlier. But apart from a one-off digital single released in 2005, and subsequent public announcements by Andy Partridge that Colin Moulding was "not interested in music anymore, and doesn't want to write," this became XTC's last big statement.

As is the case with every album on the bottom quarter of this list, Wasp Star isn't a complete and utter disaster. In fact, it starts off very strong with a trio of jaunty, blissful tunes that play to Moulding and Partridge's strengths: a faculty for earworm melodies and lyrics stuffed with witty imagery and lovely sentiment ("In Another Life" playfully pokes at the waning fire of a long marriage with references to Chippendale dancers and romance novel publishing house Mills & Boon).

But even in those songs, something seems amiss. The guitar tones are unnecessarily steely and thin, with the rhythm lines closer to computerized loops rather than actual performances, an issue likely exacerbated by the fact that Dave Gregory played no part in this recording, having left the group in 1999. The drum work of Prairie Prince and Chuck Sabo -- two of the many percussionists brought in over the years to fill the seat vacated by Terry Chambers back in 1982 -- feel stiff and mechanical. And producer Nick Davis bathes the whole thing in shades of taupe.

After the first three tracks, the band never really finds that lyrical sweet spot again. "My Brown Guitar" is a near-creepy metaphor for Partridge's dick, and "Wounded Horse" is one of his laziest, expressing his frustration with his lady's infidelity through horseracing and other equine imagery ("Well my friends all said/ just climb back in the saddle"). Moulding fares no better on his two other tracks, facing his autumn years with rueful rumination ("Boarded Up") and a strange Ivor the Engine Driver-type turn with another man's wife ("Standing In For Joe"). A steep drop in quality from the masterful statement that was Apple Venus, this isn't XTC fading away, this is fizzling out.

What an unfortunate note to end a career on.

Of course, at the time of Wasp Star's recording and release, it wasn't entirely clear that this would be the last XTC album. This was the band making good on a promise to release two successive and complementary full-lengths, this being the electrified counterpart to Apple Venus Volume 1, released a year earlier. But apart from a one-off digital single released in 2005, and subsequent public announcements by Andy Partridge that Colin Moulding was "not interested in music anymore, and doesn't want to write," this became XTC's last big statement.

As is the case with every album on the bottom quarter of this list, Wasp Star isn't a complete and utter disaster. In fact, it starts off very strong with a trio of jaunty, blissful tunes that play to Moulding and Partridge's strengths: a faculty for earworm melodies and lyrics stuffed with witty imagery and lovely sentiment ("In Another Life" playfully pokes at the waning fire of a long marriage with references to Chippendale dancers and romance novel publishing house Mills & Boon).

But even in those songs, something seems amiss. The guitar tones are unnecessarily steely and thin, with the rhythm lines closer to computerized loops rather than actual performances, an issue likely exacerbated by the fact that Dave Gregory played no part in this recording, having left the group in 1999. The drum work of Prairie Prince and Chuck Sabo -- two of the many percussionists brought in over the years to fill the seat vacated by Terry Chambers back in 1982 -- feel stiff and mechanical. And producer Nick Davis bathes the whole thing in shades of taupe.

After the first three tracks, the band never really finds that lyrical sweet spot again. "My Brown Guitar" is a near-creepy metaphor for Partridge's dick, and "Wounded Horse" is one of his laziest, expressing his frustration with his lady's infidelity through horseracing and other equine imagery ("Well my friends all said/ just climb back in the saddle"). Moulding fares no better on his two other tracks, facing his autumn years with rueful rumination ("Boarded Up") and a strange Ivor the Engine Driver-type turn with another man's wife ("Standing In For Joe"). A steep drop in quality from the masterful statement that was Apple Venus, this isn't XTC fading away, this is fizzling out.

The last album that XTC would deliver to their longtime benefactors Virgin Records, Nonsuch is a byproduct of peak CD-era hubris: a decent 10-track album padded out with filler and half-baked ideas until it ballooned up to 17 tracks and an hour-long running time.

The disc is also seemingly programmed to take into account the short attention spans of most modern music fans, as it is frontloaded with its best work. The first six tracks are peerless slices of pop, moving from the raw jangle of "The Ballad Of Peter Pumpkinhead" to the lilting "My Bird Performs" to the stately 6/8 shuffle of "The Disappointed" with giddy ease.

It's when the album hits Partridge's ode to watching his daughter ride her favorite rocking horse ("Holly Up On Poppy") that things start to go awry. The shifts in mood and tone become too jarring -- the sparkly-eyed love song "Then She Appeared" bumping unnaturally against the martial anti-conflict sentiments of "War Dance," or wedging the delicate "Bungalow" between two of Partridge's most plodding rock numbers.

A further knock on this album is how everything is covered by this audibly digital sheen. Positively everything on here sounds clipped and unnatural, but you can hear it most in poor Dave Mattacks' drums. Each cymbal crash and snare hit appears to be spilling over with ones and zeros. A bit of a slap in the face to a gent whose warm, jazz-inspired playing was so vital to folk-rock pioneers Fairport Convention.

The band still manages to grab some glory amid the chaos of Nonsuch's last 40 minutes. Dave Gregory's guitar solo on the otherwise throwaway "Crocodile" is appropriately beastly, and Colin Moulding's "Bungalow" is a perfectly rendered ode to old age (a subject that seems to be constantly on the man's mind). It's not enough, though, to rescue this top-heavy ship from sinking under its own weight.

In spite of its failings, Nonsuch did tickle some influential ears. The album netted a Grammy nomination for "Best Alternative Music Album," and radio airplay of its singles ("Pumpkinhead" and "Disappointed") in the U.S. edged it to #97 on the Billboard 200.

It also provided a final nail in the heart of the band's oft-fractured relationship with Virgin, as they pretty well gave up on promoting the album. "Wrapped In Grey" was planned as a third single, with money spent on a video and everything, but quickly withdrawn by the label. An unceremonious end to a long working relationship, and one that Partridge and co. are still feeling the effects of to this day.

The last album that XTC would deliver to their longtime benefactors Virgin Records, Nonsuch is a byproduct of peak CD-era hubris: a decent 10-track album padded out with filler and half-baked ideas until it ballooned up to 17 tracks and an hour-long running time.

The disc is also seemingly programmed to take into account the short attention spans of most modern music fans, as it is frontloaded with its best work. The first six tracks are peerless slices of pop, moving from the raw jangle of "The Ballad Of Peter Pumpkinhead" to the lilting "My Bird Performs" to the stately 6/8 shuffle of "The Disappointed" with giddy ease.

It's when the album hits Partridge's ode to watching his daughter ride her favorite rocking horse ("Holly Up On Poppy") that things start to go awry. The shifts in mood and tone become too jarring -- the sparkly-eyed love song "Then She Appeared" bumping unnaturally against the martial anti-conflict sentiments of "War Dance," or wedging the delicate "Bungalow" between two of Partridge's most plodding rock numbers.

A further knock on this album is how everything is covered by this audibly digital sheen. Positively everything on here sounds clipped and unnatural, but you can hear it most in poor Dave Mattacks' drums. Each cymbal crash and snare hit appears to be spilling over with ones and zeros. A bit of a slap in the face to a gent whose warm, jazz-inspired playing was so vital to folk-rock pioneers Fairport Convention.

The band still manages to grab some glory amid the chaos of Nonsuch's last 40 minutes. Dave Gregory's guitar solo on the otherwise throwaway "Crocodile" is appropriately beastly, and Colin Moulding's "Bungalow" is a perfectly rendered ode to old age (a subject that seems to be constantly on the man's mind). It's not enough, though, to rescue this top-heavy ship from sinking under its own weight.

In spite of its failings, Nonsuch did tickle some influential ears. The album netted a Grammy nomination for "Best Alternative Music Album," and radio airplay of its singles ("Pumpkinhead" and "Disappointed") in the U.S. edged it to #97 on the Billboard 200.

It also provided a final nail in the heart of the band's oft-fractured relationship with Virgin, as they pretty well gave up on promoting the album. "Wrapped In Grey" was planned as a third single, with money spent on a video and everything, but quickly withdrawn by the label. An unceremonious end to a long working relationship, and one that Partridge and co. are still feeling the effects of to this day.

Much like they did to close out their career, XTC followed up a pastoral "chug through the countryside," as Andy Partridge described 1983's Mummer, with a loud, brash, foul-tempered ogre of an album. And just as with Wasp Star, they ended up with a bit of a mess on their hands.

It all comes down to how ugly this record sounds. Or, to use Partridge's words, Big Express was "an iron opera, steam powered and brick encased." In other words, it sounds like a band trying to be heard over the din of a locomotive or submarine engine, with clanging and hissing in the background, a thin layer of soot covering everything, and all the overdriven instruments and vocal work peaking into the red.

This sneaks by Nonsuch and Wasp Star by dint of its momentum -- the album takes the cue of its title and moves forward at a perfect cruising speed -- and how they manage to use this sonic morass to the advantage of the songs here. Lead single "All You Pretty Girls" needs the raucous attitude and stomping percussion to help aid in its goal of becoming a modern-day sea shanty, and the dissonance between the lighter melodies of "This World Over" and "I Remember The Sun" and the music's cumbersome girth is quite impressive. Even a song as overwrought as "Seagulls Screaming Kiss Her, Kiss Her" pleasantly sticks with you, even if its burbling vocal effects and smokestack organ playing threaten its bonhomie.

Conversely, The Big Express also turns out to carry some of Partridge and Moulding's most dour songs. There's plenty of anger thrown towards the military-industrial complex ("This World Over," "Reign Of Blows") as well as XTC's shady former manager ("I Bought Myself A Liarbird"). All welcome subjects, but once the romantic tunes are dispensed with, the unrelenting vitriol starts to put unwanted tension in your shoulders.

Much like they did to close out their career, XTC followed up a pastoral "chug through the countryside," as Andy Partridge described 1983's Mummer, with a loud, brash, foul-tempered ogre of an album. And just as with Wasp Star, they ended up with a bit of a mess on their hands.

It all comes down to how ugly this record sounds. Or, to use Partridge's words, Big Express was "an iron opera, steam powered and brick encased." In other words, it sounds like a band trying to be heard over the din of a locomotive or submarine engine, with clanging and hissing in the background, a thin layer of soot covering everything, and all the overdriven instruments and vocal work peaking into the red.

This sneaks by Nonsuch and Wasp Star by dint of its momentum -- the album takes the cue of its title and moves forward at a perfect cruising speed -- and how they manage to use this sonic morass to the advantage of the songs here. Lead single "All You Pretty Girls" needs the raucous attitude and stomping percussion to help aid in its goal of becoming a modern-day sea shanty, and the dissonance between the lighter melodies of "This World Over" and "I Remember The Sun" and the music's cumbersome girth is quite impressive. Even a song as overwrought as "Seagulls Screaming Kiss Her, Kiss Her" pleasantly sticks with you, even if its burbling vocal effects and smokestack organ playing threaten its bonhomie.

Conversely, The Big Express also turns out to carry some of Partridge and Moulding's most dour songs. There's plenty of anger thrown towards the military-industrial complex ("This World Over," "Reign Of Blows") as well as XTC's shady former manager ("I Bought Myself A Liarbird"). All welcome subjects, but once the romantic tunes are dispensed with, the unrelenting vitriol starts to put unwanted tension in your shoulders.

Let's chalk this one up to youthful folly. After bursting forth into the UK indie scene with the wiry and delightfully off-kilter White Music, the band (at this point a quartet with Partridge, Moulding, Chambers, and keyboardist Barry Andrews) attempted to maintain the momentum of the first LP and their hectic touring schedule to incredibly mixed results. Or, as Partridge put it in the notes for the 1991 CD issue of this album, "Four weeks worth of songs, hastily scribbled on hotel notepaper and beermats. We were living out of carrier bags and in rental vans, making nasty noises at each other and with each other. Something had to give and here it is."

The tension within the band at that time, with the dueling egos of Partridge and Andrews wrestling over the steering wheel, is all over Go 2. The work of both songwriters on here seems strained. Occasionally that yielded some interesting results: the withdrawal itch attack of "Red" (a song that features none of Andrews' signature circus tent synth) is marvelous, and "Battery Brides" is as brooding and creepy as the band ever got. The rest, though, are just knuckleheaded efforts that never really coalesce, a sentiment that goes double for Andrews' two contributions, "Super-Tuff" and "My Weapon."

This ended up being the ideal situation for Moulding. By avoiding the slings and arrows being hurled at each other by his bandmates, he was able to knuckle down and contribute some gems here. The three tracks stacked up in the middle of side one of the original vinyl/cassette release find that perfect meeting place between the group's interest in hopped up ska, garage-born punk, and their still blossoming pop chops. Sadly, his fourth effort, the album-closing "I Am The Audience," offers up a great opening burst of firecracker guitar and organ work but resorts to a plodding groove for the rest of its three-and-a-half minutes.

The raw numbers here offer up the potential solution that trimming the conceptual fat and adding on the brilliant non-album single "Are You Receiving Me?" could have solved this album's issues. But even without the messier bits, the good stuff doesn't mesh together well. It sounds like the product of a band that stopped listening to one another, both musically and personally. "Buzzcity Talking" is too large of a sonic leap to follow "Battery Brides," as is the back-to-back "The Rhythm" and "Red." And it only makes the discordant sounds and personalities of the real duds ("Meccanik Dancing (Oh We Go!)" and "Life Is Good In The Greenhouse") glare out even louder.

Let's chalk this one up to youthful folly. After bursting forth into the UK indie scene with the wiry and delightfully off-kilter White Music, the band (at this point a quartet with Partridge, Moulding, Chambers, and keyboardist Barry Andrews) attempted to maintain the momentum of the first LP and their hectic touring schedule to incredibly mixed results. Or, as Partridge put it in the notes for the 1991 CD issue of this album, "Four weeks worth of songs, hastily scribbled on hotel notepaper and beermats. We were living out of carrier bags and in rental vans, making nasty noises at each other and with each other. Something had to give and here it is."

The tension within the band at that time, with the dueling egos of Partridge and Andrews wrestling over the steering wheel, is all over Go 2. The work of both songwriters on here seems strained. Occasionally that yielded some interesting results: the withdrawal itch attack of "Red" (a song that features none of Andrews' signature circus tent synth) is marvelous, and "Battery Brides" is as brooding and creepy as the band ever got. The rest, though, are just knuckleheaded efforts that never really coalesce, a sentiment that goes double for Andrews' two contributions, "Super-Tuff" and "My Weapon."

This ended up being the ideal situation for Moulding. By avoiding the slings and arrows being hurled at each other by his bandmates, he was able to knuckle down and contribute some gems here. The three tracks stacked up in the middle of side one of the original vinyl/cassette release find that perfect meeting place between the group's interest in hopped up ska, garage-born punk, and their still blossoming pop chops. Sadly, his fourth effort, the album-closing "I Am The Audience," offers up a great opening burst of firecracker guitar and organ work but resorts to a plodding groove for the rest of its three-and-a-half minutes.

The raw numbers here offer up the potential solution that trimming the conceptual fat and adding on the brilliant non-album single "Are You Receiving Me?" could have solved this album's issues. But even without the messier bits, the good stuff doesn't mesh together well. It sounds like the product of a band that stopped listening to one another, both musically and personally. "Buzzcity Talking" is too large of a sonic leap to follow "Battery Brides," as is the back-to-back "The Rhythm" and "Red." And it only makes the discordant sounds and personalities of the real duds ("Meccanik Dancing (Oh We Go!)" and "Life Is Good In The Greenhouse") glare out even louder.

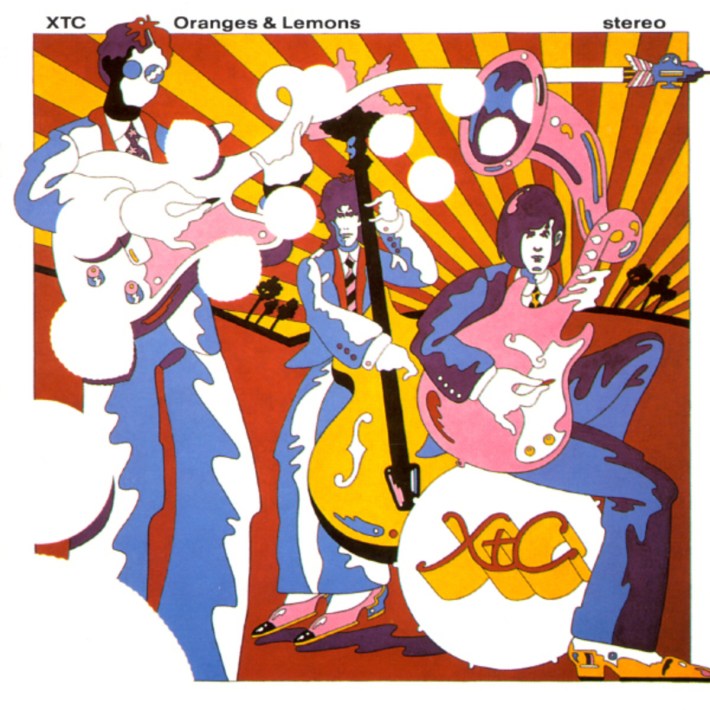

There's a fine album tucked away inside Oranges And Lemons. To find it, though, requires some mental work of scraping away the gloss and polish that first-time producer Paul Fox and engineer Ed Thacker liberally applied to these sessions, and imagining a more stern hand cutting away the LP's dead weight. And there's a fair amount to be found during its 60+ minutes.

Partridge's ethos for this album appears to be a continuation of the Dukes Of Stratosphear aesthetic -- exploring the sound and colors of their '60s influences -- but he makes the unfortunate step of trying to filter it through modern instrumentation and technology. Add to it a larger recording budget and placing the sessions in Los Angeles, and Virgin seemed to be practically begging him to overreach.

Just listen to the lead track "Garden Of Earthly Delights." Ostensibly a late-'80s rewrite of "2000 Light Years From Home," a track from the Rolling Stones' post-Sgt. Pepper's psych epic Their Satanic Majesties Request (one of Partridge's favorite albums), the five-minute long song is overfilled with ideas. Gregory's faux-sitar guitar lines and the drums (played by Pat Mastelotto, ex-Mr. Mister) are compressed to the hilt, over which Partridge piles on synth squiggles, percussion, and lost-in-space vocal asides. It's as exhausting as it gets, and it's the first track on the album.

Partridge returns to this too-generous mode throughout his 12 songs: the furtive "Across This Antheap" has voices and trumpet bleats attacking from all sides; "Here Comes President Kill Again" matches the lyrics' strident hue by choking the tune in digitized guitar washes and leaden rhythms.

As ever there are exceptions to be found. The album's final two tracks, "Miniature Sun" and "Chalkhills And Children" also brim with incident, but they manage to overcome the bloat thanks to the fact that they are simply better written songs. The former is a perfect example of Partridge's ability to spin out a long form metaphor (in this case, using imagery of the sun's wonder and danger to capture a tale of love and betrayal), the latter one of his sweetest songs about staying connected to his hometown of Swindon. Most everything else can't compare, particularly "President," a slog of sociopolitical commentary ("Here comes President Kill again/ Broadcasting from his killing den/ dressed in pounds and dollars and yen").

Oranges stays aloft thanks to those sweet-spot songs where the lyrics/melody spark and the music is restrained and taut. "The Mayor Of Simpleton" was rightfully a minor chart hit for XTC (#72 on the Billboard Hot 100, #1 on the Modern Rock chart), as it is as perfect a pop song as Partridge has ever crafted, with bright, jangly guitars and ruefully funny/sweet phrases throughout ("What you get is all real/ I can't put on an act/ it takes brains to do that anyway"). "The Loving" turns the sentiment of "All You Need Is Love" into nicely glam-dipped candyfloss. And, unlike "My Brown Guitar," Partridge's ode to his penis has a naughty swing that works nicely with the novelty hit-style lyrics ("Pink thing/spit in my eye/I'll love you for it").

Before we delve into the work of the band's other songwriter, let's heap some much-deserved praise on Dave Gregory. Ever since joining XTC in 1979, he's long served as a secret musical weapon, and on Oranges, he comes up with some of his greatest instrumental performances. Even amid the disorder of "Garden," his guitar solo is a blast of multicolored hues and pinprick notes. He deliriously channels Mick Ronson on "The Loving," and he turns over rich bluesy chords with ease on the otherwise lumbering "Across This Antheap." Listening to Gregory evolve with and elevate each song is a master class in guitar, and the album would have been even farther gone without his input.

The same can be said for Moulding. He's relegated to only three songs here, but what three songs they are. Sure, "King For A Day" is a bit of a throwaway, pseudo-Tears For Fears jam, but it's a mighty catchy one (listen, too, for the double-tracked guitar lead played forward in one channel and backward in the other). The other two tunes -- "Cynical Days" and "One Of The Millions" -- are nothing short of wonderful, addressing very adult concerns with a tuneful and almost light touch. If only there were more of Moulding's voice to counter Partridge's heavy-handedness, Oranges might have stayed more in balance.

There's a fine album tucked away inside Oranges And Lemons. To find it, though, requires some mental work of scraping away the gloss and polish that first-time producer Paul Fox and engineer Ed Thacker liberally applied to these sessions, and imagining a more stern hand cutting away the LP's dead weight. And there's a fair amount to be found during its 60+ minutes.

Partridge's ethos for this album appears to be a continuation of the Dukes Of Stratosphear aesthetic -- exploring the sound and colors of their '60s influences -- but he makes the unfortunate step of trying to filter it through modern instrumentation and technology. Add to it a larger recording budget and placing the sessions in Los Angeles, and Virgin seemed to be practically begging him to overreach.

Just listen to the lead track "Garden Of Earthly Delights." Ostensibly a late-'80s rewrite of "2000 Light Years From Home," a track from the Rolling Stones' post-Sgt. Pepper's psych epic Their Satanic Majesties Request (one of Partridge's favorite albums), the five-minute long song is overfilled with ideas. Gregory's faux-sitar guitar lines and the drums (played by Pat Mastelotto, ex-Mr. Mister) are compressed to the hilt, over which Partridge piles on synth squiggles, percussion, and lost-in-space vocal asides. It's as exhausting as it gets, and it's the first track on the album.

Partridge returns to this too-generous mode throughout his 12 songs: the furtive "Across This Antheap" has voices and trumpet bleats attacking from all sides; "Here Comes President Kill Again" matches the lyrics' strident hue by choking the tune in digitized guitar washes and leaden rhythms.

As ever there are exceptions to be found. The album's final two tracks, "Miniature Sun" and "Chalkhills And Children" also brim with incident, but they manage to overcome the bloat thanks to the fact that they are simply better written songs. The former is a perfect example of Partridge's ability to spin out a long form metaphor (in this case, using imagery of the sun's wonder and danger to capture a tale of love and betrayal), the latter one of his sweetest songs about staying connected to his hometown of Swindon. Most everything else can't compare, particularly "President," a slog of sociopolitical commentary ("Here comes President Kill again/ Broadcasting from his killing den/ dressed in pounds and dollars and yen").

Oranges stays aloft thanks to those sweet-spot songs where the lyrics/melody spark and the music is restrained and taut. "The Mayor Of Simpleton" was rightfully a minor chart hit for XTC (#72 on the Billboard Hot 100, #1 on the Modern Rock chart), as it is as perfect a pop song as Partridge has ever crafted, with bright, jangly guitars and ruefully funny/sweet phrases throughout ("What you get is all real/ I can't put on an act/ it takes brains to do that anyway"). "The Loving" turns the sentiment of "All You Need Is Love" into nicely glam-dipped candyfloss. And, unlike "My Brown Guitar," Partridge's ode to his penis has a naughty swing that works nicely with the novelty hit-style lyrics ("Pink thing/spit in my eye/I'll love you for it").

Before we delve into the work of the band's other songwriter, let's heap some much-deserved praise on Dave Gregory. Ever since joining XTC in 1979, he's long served as a secret musical weapon, and on Oranges, he comes up with some of his greatest instrumental performances. Even amid the disorder of "Garden," his guitar solo is a blast of multicolored hues and pinprick notes. He deliriously channels Mick Ronson on "The Loving," and he turns over rich bluesy chords with ease on the otherwise lumbering "Across This Antheap." Listening to Gregory evolve with and elevate each song is a master class in guitar, and the album would have been even farther gone without his input.

The same can be said for Moulding. He's relegated to only three songs here, but what three songs they are. Sure, "King For A Day" is a bit of a throwaway, pseudo-Tears For Fears jam, but it's a mighty catchy one (listen, too, for the double-tracked guitar lead played forward in one channel and backward in the other). The other two tunes -- "Cynical Days" and "One Of The Millions" -- are nothing short of wonderful, addressing very adult concerns with a tuneful and almost light touch. If only there were more of Moulding's voice to counter Partridge's heavy-handedness, Oranges might have stayed more in balance.

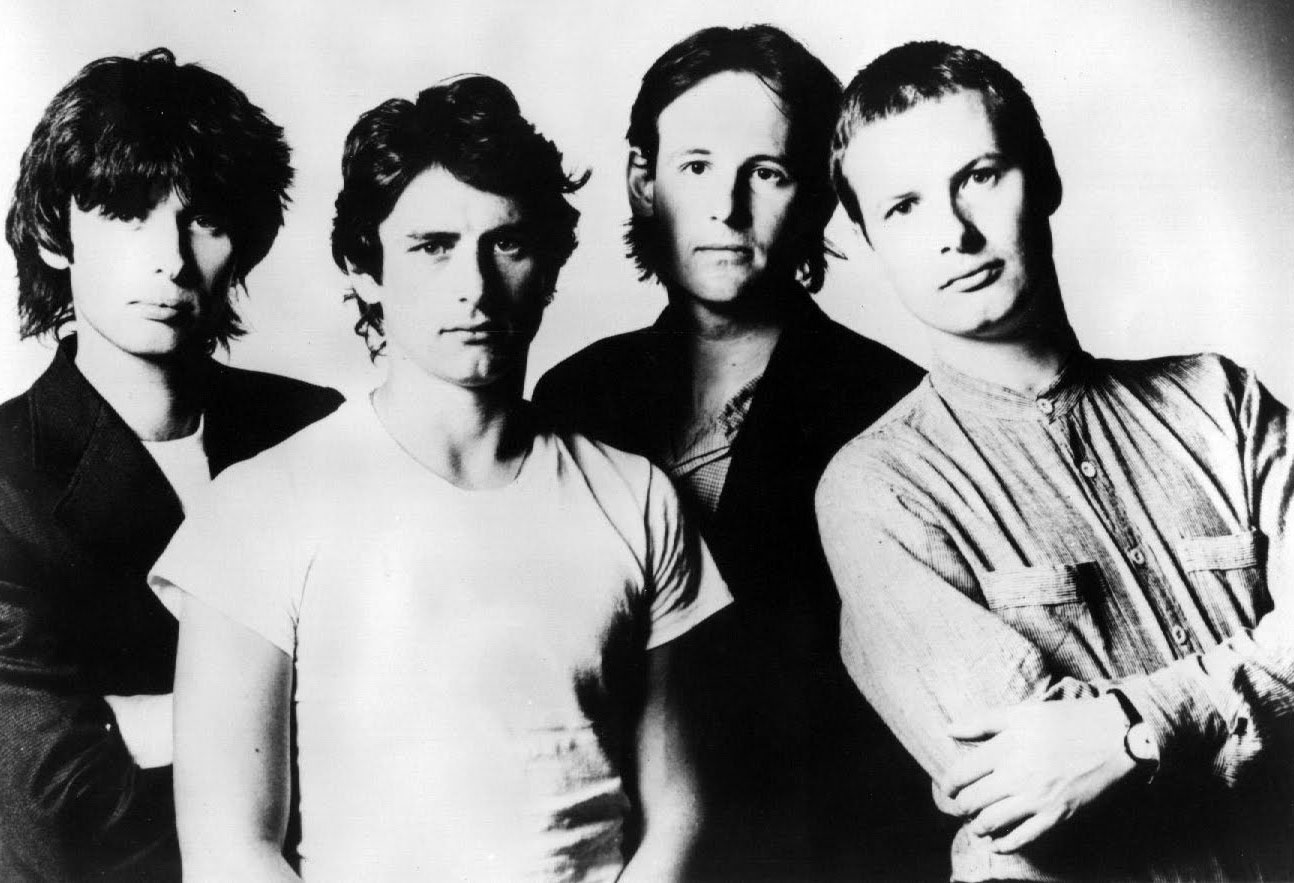

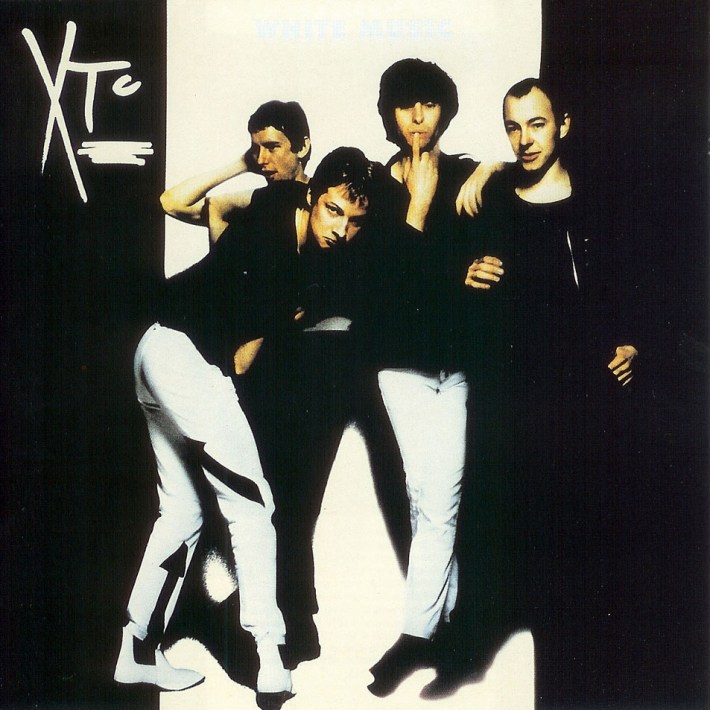

It's remarkable to consider that the same two songwriters behind this collection of scratchy, hyperactive post-punk are the same men who, two decades later, would create a masterwork of multi-colored pop. I'm sure Partridge and Moulding also look back at the skinny, furtive gents on the cover of this LP and chuckle ruefully.

By all rights, XTC's debut album features fewer moments of greatness than Oranges (a sentiment the folks who made it would hopefully agree with). But it manages to slot just above it because it is a textbook representation of the overwhelming impact of punk rock on a nation's youth.

If you have any doubts about that, give a look at this video of the band in 1974, back when XTC called themselves the Helium Kids. Note the shoulder-length hair, and the music that aims to mesh prog rock complexity into the grooves of '70s boogie rock. In just a few years, they'd all have close-cropped locks, skinny trousers, and a biting attitude that resulted in these firecracker bursts of new wave pop.

The energy certainly suits them, as this album gives the impression that could it fall to pieces or fly off the rails at any moment. But this is a road-tight quartet that has been perfecting these songs over years of rehearsals and gigs. They sound sinewy, lean, and ready for action.

By and large, this first edition of XTC had the songs to match that spirit. "Spinning Top" is two-and-a-half minutes of herky-jerky joy, capped off by Andrews and Partridge synchronizing for a quick, sci-fi soundtrack solo. The quickly dispensed with "Do What You Do" is custom built for sweaty pogo dancing, as is the snotty suburbia kiss-off "Into The Atom Age" (Andrews' organ melodies really shine on this one). Even better is the album's single "Statue Of Liberty," a devilish ode to the New York landmark that managed to get banned by the BBC due to its line of sailing beneath Lady Liberty's skirt.

When the band stumbles on this debut, though, they fall hard. They make a misguided attempt at dragging Bob Dylan's "All Along The Watchtower" into the punk age, wonky harmonica solo and all. The original version of "This Is Pop?" can't hold a candle to fist-pumping re-recording they did just a few months later. And in a rare early misstep, Moulding never seems to find his legs with this jumped-up sound on "I'll Set Myself On Fire" and "Cross Wires."

To be entirely fair to the band, White Music is a document of a group still finding its feet as songwriters and cogs in the music industry. The rest of XTC's long career turned out to be them trying to reconcile the two ideas that one could still be great at the former without sacrificing the needs of the latter. But as an opening salvo, it's a fine one that all too often gets glossed over when the band's career is explored en masse.

It's remarkable to consider that the same two songwriters behind this collection of scratchy, hyperactive post-punk are the same men who, two decades later, would create a masterwork of multi-colored pop. I'm sure Partridge and Moulding also look back at the skinny, furtive gents on the cover of this LP and chuckle ruefully.

By all rights, XTC's debut album features fewer moments of greatness than Oranges (a sentiment the folks who made it would hopefully agree with). But it manages to slot just above it because it is a textbook representation of the overwhelming impact of punk rock on a nation's youth.

If you have any doubts about that, give a look at this video of the band in 1974, back when XTC called themselves the Helium Kids. Note the shoulder-length hair, and the music that aims to mesh prog rock complexity into the grooves of '70s boogie rock. In just a few years, they'd all have close-cropped locks, skinny trousers, and a biting attitude that resulted in these firecracker bursts of new wave pop.

The energy certainly suits them, as this album gives the impression that could it fall to pieces or fly off the rails at any moment. But this is a road-tight quartet that has been perfecting these songs over years of rehearsals and gigs. They sound sinewy, lean, and ready for action.

By and large, this first edition of XTC had the songs to match that spirit. "Spinning Top" is two-and-a-half minutes of herky-jerky joy, capped off by Andrews and Partridge synchronizing for a quick, sci-fi soundtrack solo. The quickly dispensed with "Do What You Do" is custom built for sweaty pogo dancing, as is the snotty suburbia kiss-off "Into The Atom Age" (Andrews' organ melodies really shine on this one). Even better is the album's single "Statue Of Liberty," a devilish ode to the New York landmark that managed to get banned by the BBC due to its line of sailing beneath Lady Liberty's skirt.

When the band stumbles on this debut, though, they fall hard. They make a misguided attempt at dragging Bob Dylan's "All Along The Watchtower" into the punk age, wonky harmonica solo and all. The original version of "This Is Pop?" can't hold a candle to fist-pumping re-recording they did just a few months later. And in a rare early misstep, Moulding never seems to find his legs with this jumped-up sound on "I'll Set Myself On Fire" and "Cross Wires."

To be entirely fair to the band, White Music is a document of a group still finding its feet as songwriters and cogs in the music industry. The rest of XTC's long career turned out to be them trying to reconcile the two ideas that one could still be great at the former without sacrificing the needs of the latter. But as an opening salvo, it's a fine one that all too often gets glossed over when the band's career is explored en masse.

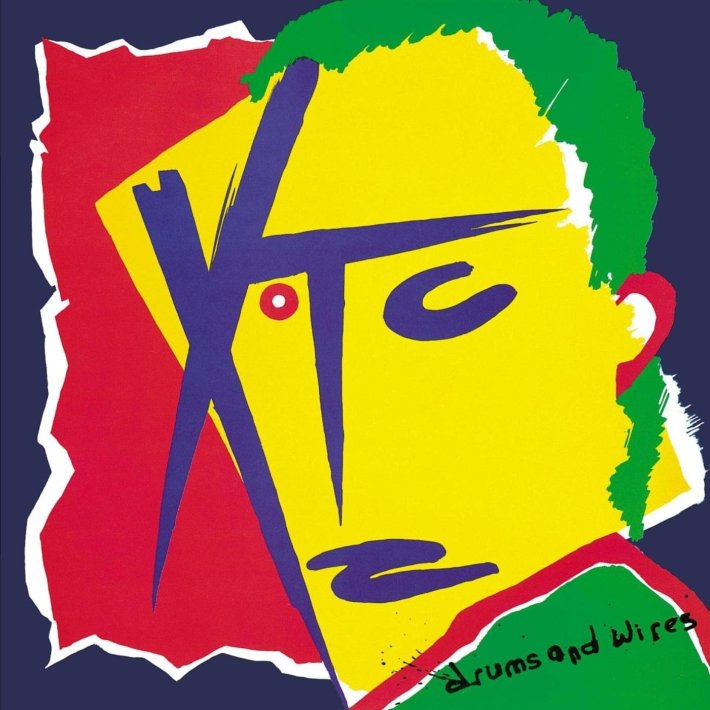

Here's where XTC started to truly come into their own. The departure of Andrews left a fairly sizable musical hole that needed filling. But instead of finding someone to replicate his carnivalesque keyboard work, they landed on Dave Gregory, a gent from Swindon who was already wowing locals with his guitar acumen. "He was one of these child prodigies who would go up on stage at the age of 14 playing in rhythm and blues groups, just as good as Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton," Partridge told the XTC fanzine Limelight in 1982.

Gregory didn't bring any flashy moves to his debut recordings with the band, but like any good player does, he melded in with the collective mindset and found ways to inject his personality into the mix. Listen for his solo on "Life Begins At The Hop," (the lead track on the U.S. release of Drums & Wires) a relaxed unfurling of muted notes that slides right back into the song's central melody before you realize what happened. Or his quick jazzy solo on the rumbly ska of "Real By Reel." Or that infectious two-note lead part that carries the verses of the U.K. edition's opening track, "Making Plans For Nigel."

The band responded to this infusion of instrumental vitality by allowing themselves to really stretch out as players and lyricists. The tempos started to slow down ("Nigel," "Millions," startling album closer "Complicated Game"), Partridge traded off lead guitar parts with the newest member, and Chambers plays with an added spark and an emphasis on perfectly placed cymbal hits.

Both songwriters train their lenses on matters of the heart and on larger subjects like geopolitics and social mores. The bookended tracks on the UK release of Drums offer great examples of the latter. Moulding thumbs his nose at the preordained lives of the upper crust on "Nigel" and the expectations of suburbia on "That Is The Way," while Partridge throws his hands up in disgust at the conservative and liberal parties with "Complicated" and presages the current state of government surveillance on "Real By Reel."

The growing pains of XTC are still present here on album #3. Partridge is a little too pleased with eye-rolling turns of phrase like "She got to be obscene to be obheard" and "Now I eat my daily bread/ and into the tape spool I'll be fed." The band also hasn't completely shaken off the dust of their agitated early days, the stiff-limbed "Outside World" being the most glaring example of this. All the elements are in place, however, and its relative success on both sides of the Atlantic ("Nigel" cracked the top 20 in both the U.K. and Canada) promised a fine future from the band.

Here's where XTC started to truly come into their own. The departure of Andrews left a fairly sizable musical hole that needed filling. But instead of finding someone to replicate his carnivalesque keyboard work, they landed on Dave Gregory, a gent from Swindon who was already wowing locals with his guitar acumen. "He was one of these child prodigies who would go up on stage at the age of 14 playing in rhythm and blues groups, just as good as Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton," Partridge told the XTC fanzine Limelight in 1982.

Gregory didn't bring any flashy moves to his debut recordings with the band, but like any good player does, he melded in with the collective mindset and found ways to inject his personality into the mix. Listen for his solo on "Life Begins At The Hop," (the lead track on the U.S. release of Drums & Wires) a relaxed unfurling of muted notes that slides right back into the song's central melody before you realize what happened. Or his quick jazzy solo on the rumbly ska of "Real By Reel." Or that infectious two-note lead part that carries the verses of the U.K. edition's opening track, "Making Plans For Nigel."

The band responded to this infusion of instrumental vitality by allowing themselves to really stretch out as players and lyricists. The tempos started to slow down ("Nigel," "Millions," startling album closer "Complicated Game"), Partridge traded off lead guitar parts with the newest member, and Chambers plays with an added spark and an emphasis on perfectly placed cymbal hits.

Both songwriters train their lenses on matters of the heart and on larger subjects like geopolitics and social mores. The bookended tracks on the UK release of Drums offer great examples of the latter. Moulding thumbs his nose at the preordained lives of the upper crust on "Nigel" and the expectations of suburbia on "That Is The Way," while Partridge throws his hands up in disgust at the conservative and liberal parties with "Complicated" and presages the current state of government surveillance on "Real By Reel."

The growing pains of XTC are still present here on album #3. Partridge is a little too pleased with eye-rolling turns of phrase like "She got to be obscene to be obheard" and "Now I eat my daily bread/ and into the tape spool I'll be fed." The band also hasn't completely shaken off the dust of their agitated early days, the stiff-limbed "Outside World" being the most glaring example of this. All the elements are in place, however, and its relative success on both sides of the Atlantic ("Nigel" cracked the top 20 in both the U.K. and Canada) promised a fine future from the band.

This was the record Go 2 wanted to be: a perfect distillation of a band sharpened and tightened by copious amounts of touring and on-the-road bonhomie so that they could get into a studio, knock out 11 songs in around two months, and get it in the stores before the year was out. But as we've already discussed, their second LP just didn't have the songs to back it up. Album #4 on the other hand …

Working again with producer Steve Lillywhite (he recorded Drums as well), XTC also found out how to make the band come across as fearsome and big as they did when performing in a concert setting. Every one of the main instruments feels so much more present than ever before. Opening track "Respectable Street" bursts forth at the 0:36 mark, the guitar sounding like an engine revving to life, with Chambers providing the rumbling pistons and Moulding rumbling like the vibrations beneath the driver's seat. Up to this point, XTC only ever hinted at being a rock band; this was the quartet claiming that title.

It's also the group's first smartly sequenced album. The first side of the vinyl/cassette version is as perfect as it gets. The last slash of "Respectable" that drops directly into the seesawing "Generals And Majors" over to the skittish "Living Through Another Cuba." They take a slight step down with "Love At First Sight," but on that last big electronic snare roll from Chambers, rolling "Rocket From A Bottle" explodes, all leading to the long dissolve of "No Language In Our Lungs." These are the well-thought-out shifts in mood and tempo and temperament that great mixtapes are made of. Side two carries a bit of that momentum forth with the fine industrial rhythms of "Towers Of London" through to the excitable "Burning With Optimism's Flames." From there, the album tails off quickly.

"Sgt. Rock (Is Going To Help Me)" did well for the band, notching a #16 U.K. chart placement in 1981, but it's a song that always played to me as unnecessarily complex (Chamber's drumbeat is downright dizzying) and, especially after such a strong run up to that point, a very lightweight musical sentiment. It's cold comfort to know that Partridge agrees, calling it "the least favorite of all my songs … I wish we hadn't released it. Something banal about it." The album closer "Travels In Nihilon" manages better, with Moulding and Partridge rising and falling together on their instruments, urged along by Chambers' tribal drum patterns. The whole thing just goes on way too long, taking up seven minutes at the end of the album, one third of which is an unnecessary coda that drifts into the sound of a rainspout.

Black Sea is also marked by a palpable fury in the lyrics. As Partridge told an interviewer about "Nihilon" in 2008, he was feeling betrayed by what the liberating spirit of punk had turned into. "At a time where I did actually get swept along with it, and I quickly saw that it was extremely cynical, and it was exactly the same as what it was supposed to be replacing. There was too much industry involved -- too fake, too controlling. It was so commercially driven." Those impressions spilled over into his explorations of capitalism ("Paper And Iron"), suburban banality ("Respectable Street"), and the Cold War ("Living Through Another Cuba"). His romantic spirit doesn't allow him to completely give himself over to this rage and frustration -- and his attempts later down the line to capture that same lightning were futile -- but for this moment, the anger looked good on him.

This was the record Go 2 wanted to be: a perfect distillation of a band sharpened and tightened by copious amounts of touring and on-the-road bonhomie so that they could get into a studio, knock out 11 songs in around two months, and get it in the stores before the year was out. But as we've already discussed, their second LP just didn't have the songs to back it up. Album #4 on the other hand …

Working again with producer Steve Lillywhite (he recorded Drums as well), XTC also found out how to make the band come across as fearsome and big as they did when performing in a concert setting. Every one of the main instruments feels so much more present than ever before. Opening track "Respectable Street" bursts forth at the 0:36 mark, the guitar sounding like an engine revving to life, with Chambers providing the rumbling pistons and Moulding rumbling like the vibrations beneath the driver's seat. Up to this point, XTC only ever hinted at being a rock band; this was the quartet claiming that title.

It's also the group's first smartly sequenced album. The first side of the vinyl/cassette version is as perfect as it gets. The last slash of "Respectable" that drops directly into the seesawing "Generals And Majors" over to the skittish "Living Through Another Cuba." They take a slight step down with "Love At First Sight," but on that last big electronic snare roll from Chambers, rolling "Rocket From A Bottle" explodes, all leading to the long dissolve of "No Language In Our Lungs." These are the well-thought-out shifts in mood and tempo and temperament that great mixtapes are made of. Side two carries a bit of that momentum forth with the fine industrial rhythms of "Towers Of London" through to the excitable "Burning With Optimism's Flames." From there, the album tails off quickly.

"Sgt. Rock (Is Going To Help Me)" did well for the band, notching a #16 U.K. chart placement in 1981, but it's a song that always played to me as unnecessarily complex (Chamber's drumbeat is downright dizzying) and, especially after such a strong run up to that point, a very lightweight musical sentiment. It's cold comfort to know that Partridge agrees, calling it "the least favorite of all my songs … I wish we hadn't released it. Something banal about it." The album closer "Travels In Nihilon" manages better, with Moulding and Partridge rising and falling together on their instruments, urged along by Chambers' tribal drum patterns. The whole thing just goes on way too long, taking up seven minutes at the end of the album, one third of which is an unnecessary coda that drifts into the sound of a rainspout.

Black Sea is also marked by a palpable fury in the lyrics. As Partridge told an interviewer about "Nihilon" in 2008, he was feeling betrayed by what the liberating spirit of punk had turned into. "At a time where I did actually get swept along with it, and I quickly saw that it was extremely cynical, and it was exactly the same as what it was supposed to be replacing. There was too much industry involved -- too fake, too controlling. It was so commercially driven." Those impressions spilled over into his explorations of capitalism ("Paper And Iron"), suburban banality ("Respectable Street"), and the Cold War ("Living Through Another Cuba"). His romantic spirit doesn't allow him to completely give himself over to this rage and frustration -- and his attempts later down the line to capture that same lightning were futile -- but for this moment, the anger looked good on him.

The edict sent down from on high (from Partridge, of course) was simple: "Why don't we make an album we don't have to reproduce on stage?" It's the kind of logic that most bands hit upon when settling into record album #5, but with English Settlement, it seemed especially notable considering the huge step forward from Black Sea it represented.

Of course, the quartet wasn't willing to shake off the strictures of rock music entirely. There's plenty of meat and gristle audible on this album. But there is far more nuance, moments of quiet, and much more texture baked into it as well.

The most noticeable additions are instrumental. Partridge's best songs are rooted in acoustic guitar work -- the flapping opening notes of "Senses Working Overtime," the rolling strum of the rhythm line to "Yacht Dance" and "All Of A Sudden (It's Too Late)." You can even tell that some tracks were likely gestated on an acoustic but then given over to its electrified cousin ("Jason And The Argonauts" and "Snowman," especially). Moulding, on the other hand, peppers these sessions with the use of a fretless bass. He has been open about the fact that he wasn't quite as adept at the instrument as others, and you can hear him wavering between notes on "Yacht Dance" and "Senses." It didn't need fixing, though, because that watery unsteadiness gives such a sense of truth to these songs, and emphasized that XTC wanted to add some humanity to their work.

It is when that notion was lost in the proceedings that things fall apart on English. If we're looking at the original, double LP release, side three feels like an absolute throwaway. That might raise some hackles, but I urge you to go dial up "Melt The Guns" at your earliest convenience. The sentiment of the song is a fine one (especially today), but it is a hiccupping, twitchy disaster, and a waste of Gregory's glistening guitar leads and Moulding's minimalist bass work. And things only get more awkward from there. "Leisure," the ode to the working man, clomps forward like a dying nag; "It's Nearly Africa" tries for a Fear Of Music-style mashup and threatens cultural insensitivity; and "Knuckle Down" has all the nuance of saying "tsk tsk" to racist acts. Good effort; failed execution.

Again, these might be forgivable offenses if the songs surrounding them weren't so damn good. "Senses" is perfection itself, building and receding in all the right ways, and threaded through with earworm melodies that helped propel it to the top 10 of the UK singles chart. Partridge tells a great story about the nasty deeds of young men in "No Thugs In Our House," propelled forward by Gregory's Cream-y lead guitar and Chambers' thrusting drums. With his four tracks, Moulding showcases the varying sides of his musical interests: reggae ("English Roundabout"), skittish new wave ("Fly on the Wall"), folksy psychedelia ("Runaways") and meat and potatoes rock ("Ball & Chain").

English Settlement also marked the end of another era of XTC. Their attempts to tour in support of this record went down the tubes after Partridge started suffering panic attacks and nervous exhaustion. As a result, the band would very rarely play live, and only for promotional TV appearances. It was also the last full album Terry Chambers would contribute to, deciding to depart the fold during sessions and rehearsals for the next LP. They scraped the ceiling of success (it's their highest charting album, hitting the #5 position in the UK) and were subsequently upended in that arena by internal issues. As close to a summation of the band's entire career as you're likely to find.

The edict sent down from on high (from Partridge, of course) was simple: "Why don't we make an album we don't have to reproduce on stage?" It's the kind of logic that most bands hit upon when settling into record album #5, but with English Settlement, it seemed especially notable considering the huge step forward from Black Sea it represented.

Of course, the quartet wasn't willing to shake off the strictures of rock music entirely. There's plenty of meat and gristle audible on this album. But there is far more nuance, moments of quiet, and much more texture baked into it as well.

The most noticeable additions are instrumental. Partridge's best songs are rooted in acoustic guitar work -- the flapping opening notes of "Senses Working Overtime," the rolling strum of the rhythm line to "Yacht Dance" and "All Of A Sudden (It's Too Late)." You can even tell that some tracks were likely gestated on an acoustic but then given over to its electrified cousin ("Jason And The Argonauts" and "Snowman," especially). Moulding, on the other hand, peppers these sessions with the use of a fretless bass. He has been open about the fact that he wasn't quite as adept at the instrument as others, and you can hear him wavering between notes on "Yacht Dance" and "Senses." It didn't need fixing, though, because that watery unsteadiness gives such a sense of truth to these songs, and emphasized that XTC wanted to add some humanity to their work.

It is when that notion was lost in the proceedings that things fall apart on English. If we're looking at the original, double LP release, side three feels like an absolute throwaway. That might raise some hackles, but I urge you to go dial up "Melt The Guns" at your earliest convenience. The sentiment of the song is a fine one (especially today), but it is a hiccupping, twitchy disaster, and a waste of Gregory's glistening guitar leads and Moulding's minimalist bass work. And things only get more awkward from there. "Leisure," the ode to the working man, clomps forward like a dying nag; "It's Nearly Africa" tries for a Fear Of Music-style mashup and threatens cultural insensitivity; and "Knuckle Down" has all the nuance of saying "tsk tsk" to racist acts. Good effort; failed execution.

Again, these might be forgivable offenses if the songs surrounding them weren't so damn good. "Senses" is perfection itself, building and receding in all the right ways, and threaded through with earworm melodies that helped propel it to the top 10 of the UK singles chart. Partridge tells a great story about the nasty deeds of young men in "No Thugs In Our House," propelled forward by Gregory's Cream-y lead guitar and Chambers' thrusting drums. With his four tracks, Moulding showcases the varying sides of his musical interests: reggae ("English Roundabout"), skittish new wave ("Fly on the Wall"), folksy psychedelia ("Runaways") and meat and potatoes rock ("Ball & Chain").

English Settlement also marked the end of another era of XTC. Their attempts to tour in support of this record went down the tubes after Partridge started suffering panic attacks and nervous exhaustion. As a result, the band would very rarely play live, and only for promotional TV appearances. It was also the last full album Terry Chambers would contribute to, deciding to depart the fold during sessions and rehearsals for the next LP. They scraped the ceiling of success (it's their highest charting album, hitting the #5 position in the UK) and were subsequently upended in that arena by internal issues. As close to a summation of the band's entire career as you're likely to find.

This could very well be the most controversial placement of any album on this list. Seen by many as a huge stumble after the relative greatness that was English Settlement, this is, by my reckoning, an overlooked classic in the XTC discography.

The first person to disagree with me might be former drummer Terry Chambers. He appears on only two tracks -- opening cuts "Beating Of Hearts" and "Wonderland" -- because he decided early on in the recording and rehearsal process that he wanted out. Speculation abounds on what tipped him over: being in England while his wife was in Australia; frustration that the band refused to tour again; the jazzy, pastoral shift in the music.

Whatever the reason, his absence is palpable on Mummer, even though it might have been the best thing for the album. I'm willing to be proven wrong here, but I don't think he could have pulled off the brush stroke shuffle beat of "Ladybird" or the auxiliary percussion tangle on "Love On A Farmboy's Wages" with the grace that stand-in Peter Phipps does. Even at his most textural -- as with his pleasurable hi-hat rolls of Settlement's "Yacht Dance" -- he stays tied to a more rockish approach to his instrument via those cracking drum fills that interrupt the swirling mood.

Partridge has referred to this album as being "bright sky blue," which is a great approximation of the summery, arms akimbo essence that swells from so many of these songs. You can almost hear the smile on his face as he sings "Beating Of Hearts," "Human Alchemy," and "Ladybird." Moulding must have been feeling much the same, as his contributions are wistful, ruminative, and, on "Deliver Us From The Elements," worshipful of the natural world.

Yet with all the straightforward sentiments of the lyrics, nothing else about these songs (save the album closer "Funk Pop A Roll") moves as you would expect them to. They open the album with a Middle Eastern-inspired beat, the "one" slapping down in the middle of each measure. "Wonderland" threatens to take off, but instead hovers in front of you, fluttering and teasing. For such a light song, "Human Alchemy" lurches and groans, Frankenstein's monster-style. And "Me And The Wind" never does settle on a time signature for very long. By the time "Funk Pop A Roll" swoops in at the end, the straight 4/4 beat and Byrds-ian guitars feel almost revelatory in the wake of what came before.

For all the struggles that XTC had with Virgin Records over the years, we should extend them some congratulations for this album. The band turned Mummer in, and the A&R department scoffed at the lack of singles on it. Dutifully, Partridge went back to the drawing table and sketched out one of his most indelible combinations of melody and lyrics, "Great Fire."

The label rejoicing at this new tune is a surprise considering how unusual it really is, with the verses in 3/4, the choruses in 4/4, and Partridge's free-jazz sax playing that is folded just so into the mix. Still, the album was saved, and the single … well, it got played a single time on BBC Radio and never charted. "Great Fire," though, works very well on the album, cutting directly between the Pentangle-like maypole dance of "Love On A Farmboy's Wages" and Moulding's hypnotic "Deliver Us From The Elements."

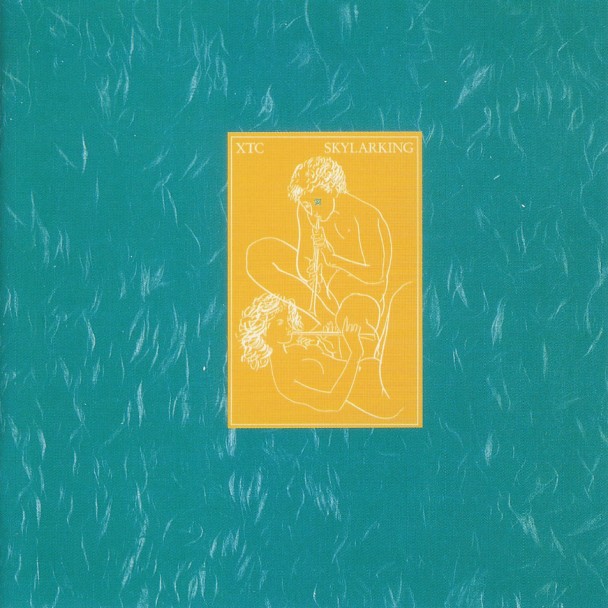

The disappointment fans and critics felt towards Mummer at the time does make sense, as they were likely hoping for English Settlement II. Looked at today, this album was really setting the table for the work they would do on Skylarking. It took the trenchant slog of The Big Express and the mischievous diversion of the first Dukes Of Stratosphear release to get there, but it was the meandering and thoughtful Mummer that lit the fuse.

This could very well be the most controversial placement of any album on this list. Seen by many as a huge stumble after the relative greatness that was English Settlement, this is, by my reckoning, an overlooked classic in the XTC discography.

The first person to disagree with me might be former drummer Terry Chambers. He appears on only two tracks -- opening cuts "Beating Of Hearts" and "Wonderland" -- because he decided early on in the recording and rehearsal process that he wanted out. Speculation abounds on what tipped him over: being in England while his wife was in Australia; frustration that the band refused to tour again; the jazzy, pastoral shift in the music.

Whatever the reason, his absence is palpable on Mummer, even though it might have been the best thing for the album. I'm willing to be proven wrong here, but I don't think he could have pulled off the brush stroke shuffle beat of "Ladybird" or the auxiliary percussion tangle on "Love On A Farmboy's Wages" with the grace that stand-in Peter Phipps does. Even at his most textural -- as with his pleasurable hi-hat rolls of Settlement's "Yacht Dance" -- he stays tied to a more rockish approach to his instrument via those cracking drum fills that interrupt the swirling mood.

Partridge has referred to this album as being "bright sky blue," which is a great approximation of the summery, arms akimbo essence that swells from so many of these songs. You can almost hear the smile on his face as he sings "Beating Of Hearts," "Human Alchemy," and "Ladybird." Moulding must have been feeling much the same, as his contributions are wistful, ruminative, and, on "Deliver Us From The Elements," worshipful of the natural world.

Yet with all the straightforward sentiments of the lyrics, nothing else about these songs (save the album closer "Funk Pop A Roll") moves as you would expect them to. They open the album with a Middle Eastern-inspired beat, the "one" slapping down in the middle of each measure. "Wonderland" threatens to take off, but instead hovers in front of you, fluttering and teasing. For such a light song, "Human Alchemy" lurches and groans, Frankenstein's monster-style. And "Me And The Wind" never does settle on a time signature for very long. By the time "Funk Pop A Roll" swoops in at the end, the straight 4/4 beat and Byrds-ian guitars feel almost revelatory in the wake of what came before.

For all the struggles that XTC had with Virgin Records over the years, we should extend them some congratulations for this album. The band turned Mummer in, and the A&R department scoffed at the lack of singles on it. Dutifully, Partridge went back to the drawing table and sketched out one of his most indelible combinations of melody and lyrics, "Great Fire."

The label rejoicing at this new tune is a surprise considering how unusual it really is, with the verses in 3/4, the choruses in 4/4, and Partridge's free-jazz sax playing that is folded just so into the mix. Still, the album was saved, and the single … well, it got played a single time on BBC Radio and never charted. "Great Fire," though, works very well on the album, cutting directly between the Pentangle-like maypole dance of "Love On A Farmboy's Wages" and Moulding's hypnotic "Deliver Us From The Elements."

The disappointment fans and critics felt towards Mummer at the time does make sense, as they were likely hoping for English Settlement II. Looked at today, this album was really setting the table for the work they would do on Skylarking. It took the trenchant slog of The Big Express and the mischievous diversion of the first Dukes Of Stratosphear release to get there, but it was the meandering and thoughtful Mummer that lit the fuse.

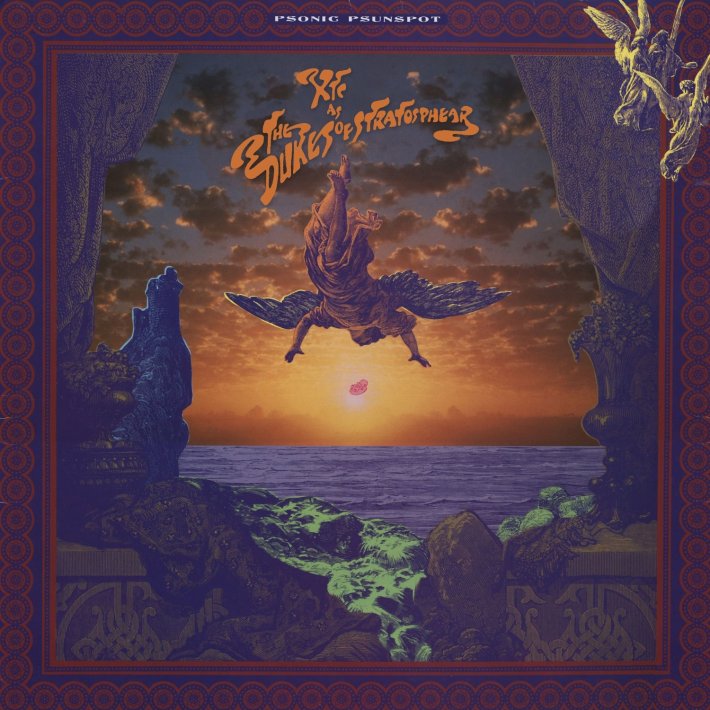

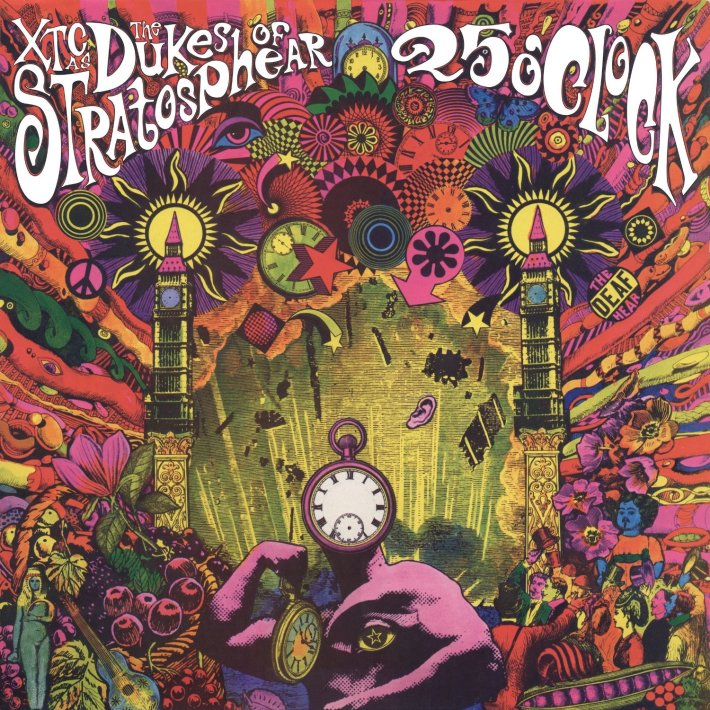

It seemed, at the time, a strange move by the band to follow up one of its most well reviewed and best-selling albums (Skylarking) with another foray into writing homages to their psychedelic pop heroes. But if they had cachet to burn, they were going to dance around the fire in velvet trousers and paisley shirts.

While this is the second release the band conceived of under the name the Dukes Of Stratosphear, it is the first one you'll see on this list, so a little history. Ever since Gregory joined the band, he and Partridge bandied about the idea of recording, as Partridge put it, "an album of songs that sound like they come from 1967." It took until 1984 for him to finally have the time and songs to execute the idea, and with the help of producer John Leckie, they decided to record an album as the Dukes, complete with groovy monikers. Partridge was Sir John Johns, Gregory chose Lord Cornelius Plum, Moulding went as The Red Curtain, and Dave's brother Ian, brought along to play drums, was E.I.E.I Owen.

The idea with Psonic was to follow the same path that they took to record the first Dukes release, 25 O'Clock: get into the studio and knock these songs out with as little fuss as possible. And considering the pains it took to birth Skylarking, is it any wonder that the three men wanted to play around with an old friend (Leckie)?

One slight difference with these Dukes recordings is that a few of the songs the group brought to the table were initially intended for XTC albums. The very Beatles-esque "Shiny Cage" was originally proffered up as a track for The Big Express, and "Little Lighthouse" was attempted and scrapped during the sessions for Skylarking. And "You're My Drug" was tossed aside for being far too similar to the Byrds.

When the Dukes took up the mantle of those songs, they amplified the parts that cut too close to their inspirations. "Drug" sounds too Byrds-ian? Of course it does. So let Gregory do his best Roger McGuinn (as guitarist) impression and make the bass sound like a fat bouncing ball. You think, as Partridge apparently did, that Moulding was trying to meld together every part of Revolver into one song with "Shiny Cage"? Then that's exactly what the Dukes will do, right down to the tabla-like drum part, a bridge that apes "Yellow Submarine," and hollow-body guitar jangle. Even the Brian Wilson-inspired "Pale And Precious" was allowed some multi-part harmonies and "God Only Knows" sleigh bells to send it on its merry way.

Like 25 O'Clock and unlike everything else in the XTC discography, it's best to approach this album with as blithe a spirit as you can. This is a straight-up lark, and the band has no compunction saying just that. What else to call an album that opens a track with the sound of a rock being tossed into a pond ("Brainiac's Daughter") and threw in a little psychedelic storybook tale narrated by a precocious little lass? With that mindset, you can simply marvel at how deeply the music of their childhood sunk into their impressionable minds, and therefore how easy it was for the Dukes and Leckie to get every last detail of those liquid, stomping, mind-altering singles and albums just right.

It seemed, at the time, a strange move by the band to follow up one of its most well reviewed and best-selling albums (Skylarking) with another foray into writing homages to their psychedelic pop heroes. But if they had cachet to burn, they were going to dance around the fire in velvet trousers and paisley shirts.

While this is the second release the band conceived of under the name the Dukes Of Stratosphear, it is the first one you'll see on this list, so a little history. Ever since Gregory joined the band, he and Partridge bandied about the idea of recording, as Partridge put it, "an album of songs that sound like they come from 1967." It took until 1984 for him to finally have the time and songs to execute the idea, and with the help of producer John Leckie, they decided to record an album as the Dukes, complete with groovy monikers. Partridge was Sir John Johns, Gregory chose Lord Cornelius Plum, Moulding went as The Red Curtain, and Dave's brother Ian, brought along to play drums, was E.I.E.I Owen.

The idea with Psonic was to follow the same path that they took to record the first Dukes release, 25 O'Clock: get into the studio and knock these songs out with as little fuss as possible. And considering the pains it took to birth Skylarking, is it any wonder that the three men wanted to play around with an old friend (Leckie)?

One slight difference with these Dukes recordings is that a few of the songs the group brought to the table were initially intended for XTC albums. The very Beatles-esque "Shiny Cage" was originally proffered up as a track for The Big Express, and "Little Lighthouse" was attempted and scrapped during the sessions for Skylarking. And "You're My Drug" was tossed aside for being far too similar to the Byrds.

When the Dukes took up the mantle of those songs, they amplified the parts that cut too close to their inspirations. "Drug" sounds too Byrds-ian? Of course it does. So let Gregory do his best Roger McGuinn (as guitarist) impression and make the bass sound like a fat bouncing ball. You think, as Partridge apparently did, that Moulding was trying to meld together every part of Revolver into one song with "Shiny Cage"? Then that's exactly what the Dukes will do, right down to the tabla-like drum part, a bridge that apes "Yellow Submarine," and hollow-body guitar jangle. Even the Brian Wilson-inspired "Pale And Precious" was allowed some multi-part harmonies and "God Only Knows" sleigh bells to send it on its merry way.

Like 25 O'Clock and unlike everything else in the XTC discography, it's best to approach this album with as blithe a spirit as you can. This is a straight-up lark, and the band has no compunction saying just that. What else to call an album that opens a track with the sound of a rock being tossed into a pond ("Brainiac's Daughter") and threw in a little psychedelic storybook tale narrated by a precocious little lass? With that mindset, you can simply marvel at how deeply the music of their childhood sunk into their impressionable minds, and therefore how easy it was for the Dukes and Leckie to get every last detail of those liquid, stomping, mind-altering singles and albums just right.

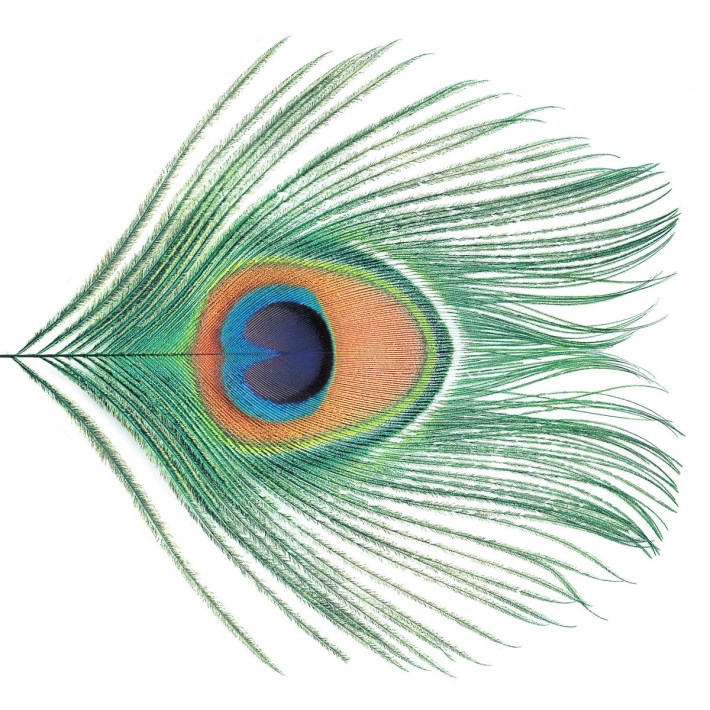

By the time Apple Venus was released, it had been seven years since the last XTC album, a long enough period that many fans were left wondering whether there would be anything new from the group. Especially because in that stretch, Partridge had busied himself writing songs for other people: the creators of the film version of James And The Giant Peach (a job he lost in place of Randy Newman), ambient artist Harold Budd, and former Lilac Time frontman Stephen Duffy. From the outside, it looked as if Partridge had just given up on his band.

In reality, the band was stuck in the middle of their strike against Virgin Records until 1997. Frustrated with their record deal and the lack of support they were given for Nonsuch, XTC remained in stasis, refusing to do any work until they could be released from their contract. Seems like such a quaint notion today, but at the time, Virgin had their hooks deep into the band, and it has only been over the last few years that the core trio have been able to wrest control of some of their work to be remastered and reissued.

Finally free, the band threw themselves into their next project with aplomb, deciding to showcase two sides of their collective personality with successive albums: one an acoustic, orchestral saunter through open fields and vast countryside, the other a grittier return to the mechanized modern world.

The contrast between the two is startling, as noted already on this list, and has only grown more so in the years since. Apple Venus is such an openhearted gesture from this band, ambitious and lush in its instrumentation and arrangements. And it finds Partridge in the midst of a songwriting hot streak he hadn't experienced since Skylarking.

Almost all the songs on Apple Venus are tied together thematically, with lyrics that reference the beauty and wonder of the natural world and that are imbued with a sense of joy at life. Think of the loping Music Hall ramble of "Frivolous Tonight," the delicious double entendres of "Easter Theatre," the heart-swollen sentiments of "Knights In Shining Karma," and the montage of village life that marks "Harvest Festival." Wrapped up in the bows of the London Sessions Orchestra recorded at Abbey Road Studios and the pair's warm singing, it's an audio hug bathed in spring sunshine.

It's also what makes the bitter taste of "Your Dictionary" so hard to swallow. I don't mean that to say that it is a bad song. You've never heard Partridge sound as direct and angry as he does here. But coming as it does after the English folk shimmy and whirl of "Greenman," it's like a dark cloud interrupting the solstice celebration. But who here hasn't carried a broken, stomped-on heart in their hands, wondering aloud, "S-H-I-T, is that how you spelt me in your dictionary?" Wisely, too, Partridge eases back on to the glen with a closing bridge that chimes and breathes deep and a hopeful glance toward the future.

Apple Venus also marked the end of Dave Gregory's tenure in the band. Frustrated with the struggles with Virgin and likely Partridge's sizable ego, he left before the album was released. Hence, he's listed only as a featured performer in the credits and is in none of the promotional photos. His instrumental presence is still evident on the record -- the wistful piano lines on "I Can't Own Her" and "Harvest Festival," and his vocal harmonies throughout -- but his absence is palpable on the follow-up recording Wasp Star. He brought so much air and light to so much of XTC's '80s and '90s work that without it, the band just wasn't the same.

By the time Apple Venus was released, it had been seven years since the last XTC album, a long enough period that many fans were left wondering whether there would be anything new from the group. Especially because in that stretch, Partridge had busied himself writing songs for other people: the creators of the film version of James And The Giant Peach (a job he lost in place of Randy Newman), ambient artist Harold Budd, and former Lilac Time frontman Stephen Duffy. From the outside, it looked as if Partridge had just given up on his band.

In reality, the band was stuck in the middle of their strike against Virgin Records until 1997. Frustrated with their record deal and the lack of support they were given for Nonsuch, XTC remained in stasis, refusing to do any work until they could be released from their contract. Seems like such a quaint notion today, but at the time, Virgin had their hooks deep into the band, and it has only been over the last few years that the core trio have been able to wrest control of some of their work to be remastered and reissued.

Finally free, the band threw themselves into their next project with aplomb, deciding to showcase two sides of their collective personality with successive albums: one an acoustic, orchestral saunter through open fields and vast countryside, the other a grittier return to the mechanized modern world.

The contrast between the two is startling, as noted already on this list, and has only grown more so in the years since. Apple Venus is such an openhearted gesture from this band, ambitious and lush in its instrumentation and arrangements. And it finds Partridge in the midst of a songwriting hot streak he hadn't experienced since Skylarking.

Almost all the songs on Apple Venus are tied together thematically, with lyrics that reference the beauty and wonder of the natural world and that are imbued with a sense of joy at life. Think of the loping Music Hall ramble of "Frivolous Tonight," the delicious double entendres of "Easter Theatre," the heart-swollen sentiments of "Knights In Shining Karma," and the montage of village life that marks "Harvest Festival." Wrapped up in the bows of the London Sessions Orchestra recorded at Abbey Road Studios and the pair's warm singing, it's an audio hug bathed in spring sunshine.

It's also what makes the bitter taste of "Your Dictionary" so hard to swallow. I don't mean that to say that it is a bad song. You've never heard Partridge sound as direct and angry as he does here. But coming as it does after the English folk shimmy and whirl of "Greenman," it's like a dark cloud interrupting the solstice celebration. But who here hasn't carried a broken, stomped-on heart in their hands, wondering aloud, "S-H-I-T, is that how you spelt me in your dictionary?" Wisely, too, Partridge eases back on to the glen with a closing bridge that chimes and breathes deep and a hopeful glance toward the future.

Apple Venus also marked the end of Dave Gregory's tenure in the band. Frustrated with the struggles with Virgin and likely Partridge's sizable ego, he left before the album was released. Hence, he's listed only as a featured performer in the credits and is in none of the promotional photos. His instrumental presence is still evident on the record -- the wistful piano lines on "I Can't Own Her" and "Harvest Festival," and his vocal harmonies throughout -- but his absence is palpable on the follow-up recording Wasp Star. He brought so much air and light to so much of XTC's '80s and '90s work that without it, the band just wasn't the same.

The initial plan with this mini-album was to have Virgin claim that it was a lost '60s-era recording that they'd recently dug out of their vaults and decided to release. But considering how poorly XTC's last two albums had fared commercially and critically, is it any wonder that they let the cat out of the bag on this one?

As with Psonic Psunspot, the follow-up Dukes record, this is the sound of five guys having a blast in the studio. The only goal was to make the music sound as close to the world of the psychedelic '60s as possible. They succeeded at every turn, and by not laboring over every last detail of their own songwriting, Sir John Johns and The Red Curtain come away with insta-classics.

There are connections to songs and artists from the past with each one -- "Bike Ride To The Moon" is a riff on Tomorrow's 1968 single "My White Bicycle," the title track works the same cresting magic as the Electric Prunes' "I Had Too Much To Dream (Last Night)," and Moulding gives lyrical nods to Zager & Evans' "In The Year 2525" all over "What In The World??…" -- but they never come across as mannered as they sometimes did on Psonic. The tunes are instead fluffy and varied and trippy, like staring too long into one of those food coloring light shows that would play behind bands at the Winterland.

Something like this also provides a great example of just how good Partridge and Moulding could be as songwriters. Once the band was finally given the green light to try this little experiment (with the smallest budget Virgin would relent to), Partridge quickly knocked together four songs. And in the studio, the group pulled "The Mole From The Ministry" completely out of thin air. Yet each one is chock-a-block with great melodies and memorable lyrics that nailed all the psych signifiers (vibrations, rainbows, dream telephones, etc.).

Again, let's give a small measure of gratitude to Virgin here. Not only for letting the band go off on this little excursion, but also because the label's paltry outlay of cash (£5,000) meant that XTC was only able to afford two weeks in the studio and therefore only able to record these six songs. So there was no time for fluff or experimentation or (as the demos appended to the 2009 CD reissue of this release reveal) lesser material. This is trim, compact, and perfect.

25 O'Clock is also incredibly important in context, as it allowed the band to put an extra spring in their creative step before returning to the studio to take on the recording of the next proper XTC album. As with Mummer, without this record and the bleed-over of these sessions, there would be no Skylarking.