The first single from Weezer's new album, Everything Will Be Alright In The End, opens with an apology. That song, of course, is "Back To The Shack," and that apology is contrite: "Sorry guys, I didn't realize that I needed you so much/ I thought I'd get a new audience, I forgot that disco sucks/ I ended up with nobody and I started feeling dumb/ Maybe I should play the lead guitar and Pat should play the drums."

It's not hard to pinpoint the choices and events for which Rivers Cuomo is apologizing: Weezer never went disco, but at their nadir -- 2009's Raditude -- they did work with such off-brand, chart-minded guests as Jermaine Dupri, Lil Wayne, and Dr. Luke. And yes, while touring for that record, Patrick Wilson did step out from behind the drum kit to play guitar -- giving Cuomo the freedom to put down his own axe and roam the stage unencumbered. Make no mistake: That shit sucked. Cuomo should apologize for it, because it was enervating, dispiriting, embarrassing garbage. But really? That was just rock bottom -- Weezer had been making bad choices for YEARS to that point.

When I say "bad choices," I'm not even talking about the manipulative and exploitive behavior that fueled and followed Weezer's first two albums. Yes, the Rivers Cuomo who made the "Blue Album" and Pinkerton was a deeply fucked-up person, but the art he produced addressing and wrestling with those issues was undeniable. I'm talking about everything else, starting with the robotic, dispassionate "Green Album," followed by the uneven and willfully difficult Maladroit. And those were relative high points! After that, things got ugly: 2005's Make Believe and 2008's "Red Album" were introduced, respectively, by the singles "Beverly Hills" and "Pork And Beans" -- utterly reprehensible, indefensible trash polluting albums whose most enthusiastic defenses never rose beyond "not as bad as everyone says" and "occasionally interesting." By the time they got to Raditude, the Weezer brand was already badly devalued. That album didn't come as much of a surprise or even a disappointment -- Weezer were already a creepy, hollow simulacrum of a once-great band.

The surprise, such as it was, actually came a year later, when Weezer released Raditude's follow-up, Hurley. By no means was Hurley a flawless album; like Raditude, it featured some dubious choices (a song co-written by Linda Perry? Another song co-written by Desmond Child? That title? That goddamn cover art?). But it was focused and direct and, y'know, not bad. It sounded like Cuomo gave a shit. He was scared about getting older, burning out, wasting his gifts, and in songs like "Brave New World," he sang about that: "I've been scared to make a move/ so much left for me to prove/ I guess it's time for me to show what I've got."

That was more than four years ago. At that point, Weezer were cranking out an album a year, and padding that output with enough ancillary content to fill a warehouse: an odds-and-sods compilation; a Record Store Day EP (which included collaborations with Kenny G and Sara Bareilles); a Christmas album; four collections of Rivers Cuomo's home recordings ... No one could have been faulted for failing to notice Hurley amid that deluge, and even for those of us that did notice, Hurley was little more than an encouraging sign, a sigh of relief, a momentary pause in the cycle of abuse. In those songs (some of them, anyway), Cuomo displayed a sense of awareness. He seemed to recognize that somewhere along the way he had lost control of his career, had grown complacent and careless, and he wanted to take it back. He wasn't apologizing for anything, exactly, but he was clearly eager to silence the criticism that must have grown deafening. And he wasn't coy about this! The Hurley track "Trainwrecks" includes the lyric, "Someday we'll cut our critics down to size/ We fall but then we rise."

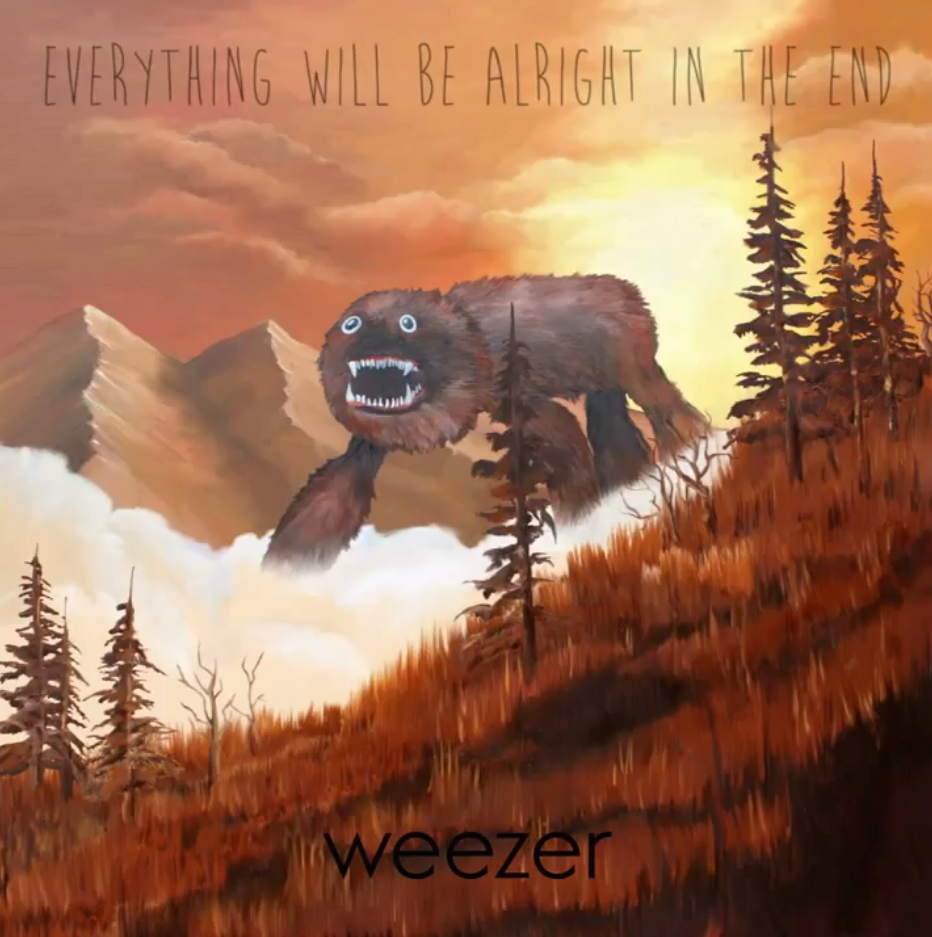

"Back To The Shack" would have fit well on Hurley; the new song echoes that old album's lyrical themes: the ultra-literal meta-commentary, the confessional self-awareness, the author's need to engage with listeners on the subject of his career. But more importantly, "Back To The Shack" is merely a so-so song with the noblest of intentions, and Hurley is merely a so-so album with the noblest of intentions. Everything Will Be Alright In The End, on the other hand, doesn't have room for so-so songs -- intentions be damned -- because it is a great record.

All right, all right, let me dial that back a notch: I'm grading on a curve here; Everything Will Be Alright In The End is maybe not a great record in the grand scheme. Weezer have made exactly two great records in the grand scheme; they are two of the best records of their decade, and if you are reading this review, you probably know them by heart. Weezer will never again make a record on that level because Rivers Cuomo will never again be that young. This life offers only a small window for any artist to convincingly write and deliver a line like "I'm dumb/ she's a lesbian," and for Rivers Cuomo, that window has long since slammed shut. If the Rivers Cuomo of 2014 were to offer up such a confession, it would come off either deeply insincere or deeply gross or both. Needless to say, Weezer's '90s albums are great precisely because of lines like "I'm dumb/ she's a lesbian," so the Rivers Cuomo of 2014 is kind of screwed. And, to an extent, so are his fans: Why stick with an artist whose best days are, by nature, behind him? Why continue to follow an artist who will never again reach the heights that defined his career?

Answers to those questions vary from artist to artist, and from fan to fan, but here are my answers as they pertain to Weezer: I have a lot of intense memories tied up with those first two Weezer albums, so I have some emotional investment in the band. Furthermore, as much as Weezer might have fucked everything up, they're still more interesting to talk about and think about than many of their peers who haven't really fucked up at all. Finally, to my ear, every Weezer record (with the exception of Raditude) has at least a couple bangers, so why would I want to miss out on those? The truth is, I love Rivers Cuomo's voice, and I love his guitar tones, and I love his melodic instincts, so I keep coming back -- and yeah, he disappoints me a lot, but he still hooks me now and then, he still brings it once in a while, he still surprises me, some times more than others.

And this time? This time his voice and guitars and melodies sound better than they have in ages, maybe better than they've ever sounded. This time he blew me away.

EWBAITE opens with "Ain't Got Nobody," which pretty immediately announces the album's intentions: 75 tons of guitars smash into your cranium like a piano falling out of the sky, Cuomo attacks his lyrics as if he's fighting them into a corner, tempos shift with balletic precision, Cuomo rips through an EVH-style solo, and there's a furiously intense "doot-doot-doot-doot-de-doot" sing-along/war chant at the song's towering apex. By that point, I think, either you're in or you're out on EWBAITE. Me, I was all-in by the end of the second verse.

It's not all as good as "Ain't Got Nobody" -- the next song on the album is "Back To The Shack," which throws off the momentum considerably -- but very often, it's even better. All the songs here sound like "classic" Weezer, although the production is closer to "Blue Album" than Pinkerton. To that end it's tempting to credit the band's resurgence to producer Ric Ocasek, who also helmed "Blue Album," but I'm hesitant to overpraise Ocasek because he was behind the boards for the "Green Album," too, and the "Green Album" is a flat, airless chore. EWBAITE, on the other hand, bursts with life, color, and exuberance.

By my count, there is one outright dud here ("Back To The Shack," which is the worst song on the whole album by a mile), and two songs that feel somewhat generic ("Lonely Girl" and "Go Away," although the latter is aided immensely by guest vocalist Bethany Cosentino, whose presence not only provide's Cuomo's narrator with a strong and suitable foil, but also some sweet harmonies). Those are the relative misses; everything else is a total hit, with at least three songs -- "Da Vinci," "The British Are Coming," and "Foolish Father" -- in contention for the album's best. "Da Vinci" probably falls short for its cringe-worthy lyrics (the line about Ancestry.com is just about unforgivable) even though its chorus is a blast and its bridge is pure joy, while "Foolish Father" probably wins for its climactic structure: If you don't get goosebumps when the guitars drop out and the children's choir comes in singing "Everything will be all right in the end" -- and then, if your heart doesn't start pumping in double-time when the guitars fall back into place behind those vocals -- then you and I just hear music differently. Because when I get to that point -- every single time I listen to that song, no matter how many times I hear it -- I am flying.

And I'm flying for a while, too. Frankly, the real highlight might be the three-song suite that follows "Foolish Father" to close out the album: "The Futurescope Trilogy," which is made up of three sections called "The Wasteland," "Anonymous," and "Return To Ithaka." "The Futurescope Trilogy" is largely instrumental (only "Anonymous" has any lyrics at all, and those are pretty minimal); Cuomo just layers guitars and keys and more guitars (and then more guitars) till the thing is the size of a skyscraper. Every climax is topped by yet another climax. I'm pretty sure Cuomo stole this trick from Andrew W.K., whose first two albums are filled with such monstrous constructions, songs in which the words are totally irrelevant -- the vocals are just another instrument used to help build momentum and grandeur. By the end of "The Futurescope Trilogy," Weezer seem as worked up and as wiped out at they did at the end of Pinkerton's "Across The Sea": It's an entirely life-affirming, awe-inspiring piece of music.

It is perhaps not a coincidence that EWBAITE's most cathartic moment comes with so few lyrics, because lyrics are the only thing separating Weezer's two truly great albums from this merely relatively great one. According to Cuomo, via a recent interview with Rolling Stone, EWBAITE was conceived as a triad, a single album separated into three individual concepts, with each song focusing on one of three distinct lyrical themes: There's what he calls the "Belladonna" section ("classic girl songs"), the "Panopticon Artist" section (songs about his relationship with his fans), and the "Patriarchia" section ("songs about father figures").

Some of the songs fit neatly into the prescribed categories, others feel like they could be be slotted into ANY of those categories, and still others feel like they were never intended for any such categories whatsoever. It's fine, of course, if Cuomo strayed from his initial compartmentalization conceit, or if his definitions of the terms "Belladonna," "Panopticon," and "Patriarchia" (that last one is Cuomo's own coinage) were broader than he managed to express in that interview. It does, though, make it harder to understand what he was trying to accomplish, and thus determine whether he was successful. The worst aspects of EWBAITE are its lyrics, especially in those songs belonging to the "Belladonna" and "Panopticon Artist" sections of the album. When those songs are great, they are great because the music overcomes the shortcomings of the words. Part of what makes "The British Are Coming" such a highlight is the fact that Cuomo sounds so emotionally invested in his historical subject matter -- he plays a more convincing Paul Revere than he does a lovesick teenager.

It's also more interesting to hear him apply his gifts to a song about the Boston Tea Party than a song about his conflicted relationship with his fans, especially because that conflict seems so broad. On "I've Had It Up To Here," Cuomo is frustrated: "I tried to give my best to you/ But you plugged up your ears." On "Eulogy For A Rock Band," he's mournful: "Adios rock band that we loved the most/ This is a toast to what you did/ And all that you were fighting for." And, again, "Back To The Shack" is an apology: "I had to go and make a few mistakes so I could find out who I am/ I'm letting all of these feelings out even if it means I fail." But while it's nice to hear such apologies, they're no longer necessary. He obviously hasn't failed. He called it back in 2010, on "Trainwrecks," on Hurley: He fell, but he's risen. Everything Will Be Alright In The End more than redeems Rivers Cuomo. His challenge now is figuring out what he wants to say next.

//

Everything Will Be Alright In The End is out 10/7 via Republic. You can stream it now at iTunes.