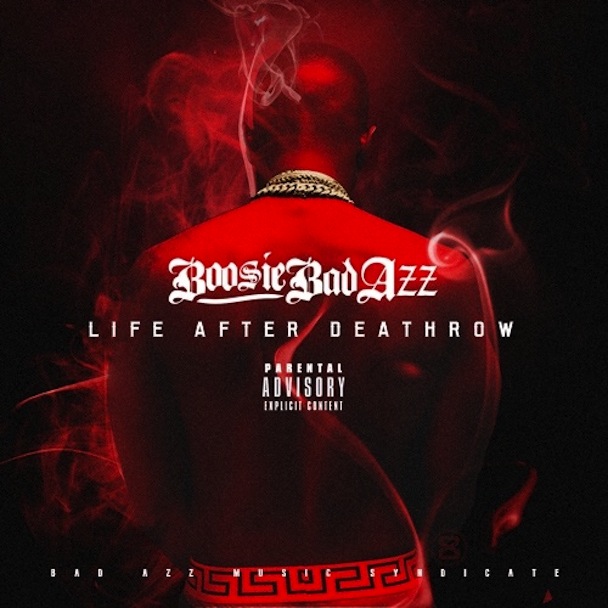

Once upon a time, Lil Boosie made party songs. He was great at it. The party songs never dominated the Baton Rouge rapper's catalog, and you sometimes got the impression that he didn't like doing them. Boosie started off as a gangsta rap child star, and by the time he got around to making Ghetto Stories, his great 2003 collaborative album with Webbie, he's matured into a wizened seen-it-all street rapper, squawking about impossible hardships in a voice that sounded like a feral cat on helium. But Boosie's biggest hits were his party songs. Ratchet music, the prim and minimal strain of party-rap that's currently dominating West Coast rap, got its name from a 2005 Boosie single. Once, on assignment for King magazine, I stood behind Boosie on an Orlando parking-lot stage and watched a euphoric crowd shout Boosie's verse from the "Wipe Me Down" remix -- "B-O-O-S-I-E B-A-D-A-Z-Z THAT'S ME!" -- back at him, and it ranks as one of my favorite live-music memories ever. The way he howled "yeeeaaauuuhh!" halfway through his verse on Webbie's "Independent" is an all-time party gauge: If you're at the club and everyone yells that word along with Boosie, you're among the right people. So Boosie had that whole party-rap thing down cold, whether that was what he wanted to do or not. But then, in 2008, Boosie was arrested on a marijuana charge and somehow ended up spending the next six years in prison on various drug charges. He also went up against a murder charge in one of those befuddling cases where the prosecution attempted to use his rap lyrics as evidence against him. He beat it. He's home now, finally, as of this past March. But he's not in a partying mood, and you cannot blame him.

"Murder Was The Case (Intro)," the first song on Boosie's excellent new Life After Deathrow tape, repurposes Snoop Dogg's "Murder Was The Case" and just lets Boosie vent about the idea that he was facing death. It's tense and tough and glorious. "They said, 'We got you on six bodies and two attempt,'" Boosie sneers at one point. "I said, 'Sir, you're lying. Because I don't do attempts." A few songs later, he asserts, "Part of my life's like an old-time Western," and it's hard to argue once you picture that scene. On that first song, Boosie is Clint Eastwood or Robert Mitchum, staring at the gallows and baring his teeth at them. The next song is called "I'm Comin' Home," and title aside, it has no interest in releasing any of that tension. On that song, and on much of the rest of the tape, Boosie snaps on all the people who abandoned him and his family, who thought he'd be in prison forever: "Three or four bitches, they told me lies / Told them I was coming home, they rolled the eyes."

He returns to that idea over and over, getting stuck on the people who showed him insufficient loyalty, imagining what'll happen if and when he goes off to prison again: "I ain't forget, some niggas ain't send me shit through hard times / Niggas I fucked with forgot my son's Jordan size." He sounds incensed, wounded, cornered. There are songs where he talks about the things he's earned, about the fact that he can provide for his kids now. There are moments of levity: "Persian rugs in my home, flatscreens up in my bathroom / Talking parrots in my kitchen saying, "Hi, Boosie Boo.'" (Boosie's parrot impersonation on that line is just the best thing.) But even on that song, he can't stop fuming about betrayal, and it's immediately clear that he's flaunting all this shit, at least in part, to rub his wealth in these people's faces. It's revenge spending.

Boosie's voice is an uncontainable fired-up honk, and it's a great instrument to convey this sort of rampant bitterness. More than anyone in rap, Boosie knows how to make that voice cut through any noise around it; even a Danny Brown sounds staid in comparison. When I interviewed Boosie years ago, he didn't talk in that voice. I asked him about it, and he said that people who rapped in their regular speaking voices weren't being creative. But if Boosie's rapping voice is a put-on, a character, it's an instinctive and emotionally powerful one. Life After Deathrow isn't an emo-rap mixtape, and it has plenty of straight-up tough-motherfucker songs. The mid-tape troika of "No Juice," "Trouble," and "Cruisin" makes for the hardest 13-minute stretch in recent memory, with Boosie snarling threats over thundering throwback old-school 808-heavy Southern beats. (There are no production credits on Life After Deathrow, but Boosie doesn't seem to be working with the shamelessly hooky synth-funk producer Mouse On Da Track anymore. Instead, these are hard and spacious and impressively well-mastered and bass-heavy tracks. They all work beautifully for him.) Later, on "Young Niggas," Boosie and one of his stylistic descendants, the D.C. rapper Shy Glizzy, trade off running-wild shit-talk with absolute relish. "Facetime" is an R&B song with Trey Songz, and there are a few sex-focused things in there as well. But the heart of the tape is Boosie coming home after six traumatic years, looking around, and hating everything he sees. It's intense, hungry, bruised music.

My favorite track on Life After Deathrow is "I'm Wit Ya," a sparse 808 slapper that Boosie uses to pull back from his own problems and to look at the lives of the people who are listening to him. On that song, Boosie raps to specific fans, people he knows are going through hard times: "You probably listening to me now, going through some real shit / Granny in the hospital and she real sick / Attitude with everybody, being a real bitch / Because losing your granny, you ain't ready to deal with." He imagines a 14-year-old catching gonorrhea, being too scared to see the doctor, listening to him. He imagines the guy who just lost at dice, ignoring calls from his girl, freaking out inwardly, listening to him. "I'm with you," he tells everyone listening. "I know that feeling." Rap is a subjective, personality-driven music, and you're supposed to empathize with the triumphs and the struggles of the person rapping. That person is not necessarily supposed to empathize with you; it's not how the genre works. But here's Boosie interrupting his own intense personal freakout, breaking the fourth wall, talking directly to the people he imagines listening to him. It's a generous moment, and a moving one. And the best part about it: The people who listen to him are probably going through the things he's rapping about. Boosie is a cult hero in some of the poorest, most dangerous areas in our country. A friend of mine has a story about his car being stolen but later recovered by police, finding all these Boosie mixtapes in his glove compartment when he got his car back. There are people out there who need Boosie, and for those people, he's just made a great mixtape, one of the year's best. It's good to have him back.

Download Life After Deathrow at DatPiff.