How appropriate that Pink Floyd would find their beginnings in the same year that saw the first person walk in space. It's a fitting foreword to the band's story which, over the last fifty years of their existence, has seen them embrace the rarity and mythos that is rock and roll legend with a disarming sense of apprehension, paranoia, and oftentimes rage. Pink Floyd's most distinctive quality is likely the very thing that provided the greatest friction for the members themselves. While their contemporaries honed in on every brilliant pop music formula from places like Liverpool and Southern California, Pink Floyd's music quickly transformed into both a cautionary tale for the easily starstruck and a deeply personal narrative that became increasingly bleak and, at its most powerful, utterly heartbreaking.

The story of the band's beginnings has been well documented with all manner of devoted fans eager to point out the fact that after several name changes (which included the always delightful and mildly prophetic Meggadeaths), the art students-turned-musicians derived the final permutation of the band's name from blues artists Pinkney "Pink" Anderson and Floyd Council. Originally called "The Pink Floyd Sound," the name was an off-the-cuff moniker created by original vocalist/guitarist Syd Barrett in what would mark an almost cruel prelude for a band who despite earning every possible level of fame and fortune, would never be able to fully come to grips with those realities of losing friends, family, and even themselves along the way.

While the music of Pink Floyd has, for the most part, never embraced the happy-go-lucky ethos of so many of the band's popular music counterparts in the late '60s, the disparity between the band's sound during the brief tenure of vocalist/guitarist Syd Barrett and what came in the wake of his departure is noteworthy when considering the whole of the band's career. Barrett's friendship with band mate and eventual sole lyricist and bassist for Pink Floyd, Roger Waters, culminated in the artistic relationship that would create the wholly distinctive sound on the band's debut, The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn. Primarily a blues band in their earliest days, it was not until Barrett took on the role of frontman and lyricist that Pink Floyd began to distance themselves both sonically and thematically from their contemporaries.

Having already established themselves as a force in the London underground of experimental music, the band's 1967 full-length debut was met with considerable success both critically and commercially, though the celebration would be cruelly brief due to what had quickly become Barrett's now completely unhinged mental state. The subject of endless speculation and mythology, Barrett's struggle with mental illness was of course tragic in its own right as a viciously unforgiving disease, yet the effects were undoubtedly driven to insurmountable levels once brought under the microscope of celebrity and media scrutiny. Along with Waters, Richard Wright (keyboards), and Nick Mason (drums), Barrett's role in Pink Floyd would extend far beyond the reach of Piper and into the very heart of some of rock and roll's most flawless and perfectly realized albums.

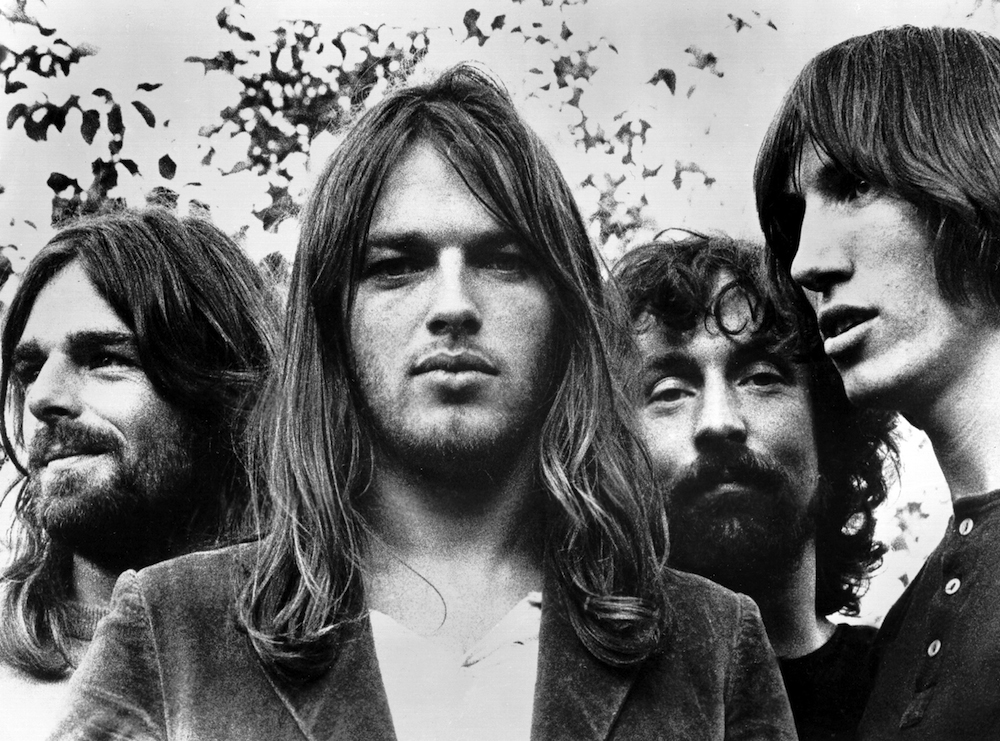

With Barrett's mental state rapidly deteriorating to the point of crisis, his band mates decided to bring on a young guitar player from Cambridge named David Gilmour as an additional member. Familiar with the band and even more so with Barrett himself, as the two had traveled and studied together, Gilmour's addition at the end of 1967 would prove to be a game changer for a band who'd already garnered interest from critics and fans alike for taking experimental risks. Just two months after a photo shoot which showed a clearly disconnected Barrett standing among his band mates, Pink Floyd parted ways with the troubled yet immensely talented musician in March 1968.

Over the course of the next fourteen years, with Gilmour taking over for Barrett on vocals and guitars, and with Waters writing the lyrics, Pink Floyd would venture into a progressively darker sound as confessional as it was prophetic, with the music manifesting the pathos and disquiet of its individual creators. Of course the definitive thematic focus of Pink Floyd is not solely linked to the experience of watching their band mate's gradual mental breakdown. Waters was as quick to explore the literal and metaphorical misgivings he had regarding Western patriarchy as he was in delving into a merciless kind of self-awareness regarding the industry hivemind and his unavoidable role as an integral part of its machinery.

Though forever (and justifiably) categorized as a "psychedelic band," Pink Floyd's music has always thrived and found the full depth of its power in the cruel reality of its presentation. From the thematic structure of albums such as Wish You Were Here or The Wall to the more free form and ethereal compositions of Meddle and Atom Heart Mother, Pink Floyd's narrative has remained largely consistent in the disarming and powerful fragility of its delivery. Though the culmination of grandeur and spectacle became fully realized from a visual standpoint with 1979's The Wall, the full scope of Pink Floyd's music had always been as colossal as the space it inhabited.

Occasionally the music world is afforded the anomalous perfection of those bands who seem destined for legend even at their very beginnings. Though Pink Floyd is certainly a band of unequivocal legend in rock and roll's history, theirs is not a story of perfection or even near-perfection. From the idiosyncratic keyboard and synth tremors of Richard Wright to Nick Mason's spatial yet exacting drumming to the frantic howls and sneering cynicism of Waters paired alongside the achingly lonesome guitar and vocal work of Gilmour, Pink Floyd's story is one that capitalized on the various imperfections and frailties of its members.

Last year, twenty years after their last full-length (1994's The Division Bell), Pink Floyd released a post script of sorts by way of The Endless River -- an album that, according to Gilmour himself, was a kind of an homage to Richard Wright, who succumbed to cancer in 2008. With fifty years of existence, the story of Pink Floyd is a narrative unlike any other in rock and roll, not for the fact that the band explored nearly every sonic and lyrical corner of the unconscious mind, but because they allowed listeners the opportunity to come along for that journey and to experience with the band those dark and harrowing realities of human existence.

It happens to the best of bands. For most groups, the death groan is an arduous process replete with near-embarrassing attempts to drain every last drop of dignity from an otherwise nearly untouchable career. For a few, the end reads much like the post-script to creative exhaustion, with the band giving a nod to their work without fully delving into what's likely an already spent creative hive mind. For Pink Floyd, the end came by way of a very fragmented glance at the pathos that had defined their sound and, to a large degree, the reality of their personal lives as well.

Twenty years after what many assumed was the band's unofficial farewell with 1994's The Division Bell, Pink Floyd released last year's The Endless River. Explicitly marketed as a swan song for Richard Wright, The Endless River is primarily an instrumental album pieced together from previously unreleased material largely composed by the founding member and keyboardist who passed away in 2008. Written and recorded during The Division Bell sessions, Wright's material is immediately reminiscent of that album's synth wash atmospherics with Gilmour adding in his blues descant right on cue. And that's just the thing here. It's a beautiful rendering of what made Wright such a veritable force in the band, but the music here is a formulaic response.

Gilmour's outstanding effort in 1994 was largely due to his refocusing the band's compositional framework as it had always been intended. That is, the music of Pink Floyd works best when there's equitable instrumentation. Sure, there's the solo flair and the justifiable moments of virtuosic prowess, but the band's nearly matchless power has always derived from the musical solidarity they shared against the odds of their subject matter. I'm not so cynical as to assume that The Endless River was a release purely conjured up by the marketing savvy of Gilmour, and even if that were the endgame it'd be an exercise in petty hypocrisy to dismiss the album entirely.

From a thematic standpoint, the album's source material is all too familiar. Another member lost. Another elegy. While much of that melancholy is lost in the New Age atmospheric yawn of the album, the familiarity of Wright's keyboard matched alongside Gilmour's characteristic guitar is an elegant reminder of just one of the many components that contributed to the group's success. Perhaps it's precisely the way a band like Pink Floyd needed to end, with a mournful if fragmented look at a career that had burdened itself with the same things to great success and equally as devastating losses.

It happens to the best of bands. For most groups, the death groan is an arduous process replete with near-embarrassing attempts to drain every last drop of dignity from an otherwise nearly untouchable career. For a few, the end reads much like the post-script to creative exhaustion, with the band giving a nod to their work without fully delving into what's likely an already spent creative hive mind. For Pink Floyd, the end came by way of a very fragmented glance at the pathos that had defined their sound and, to a large degree, the reality of their personal lives as well.

Twenty years after what many assumed was the band's unofficial farewell with 1994's The Division Bell, Pink Floyd released last year's The Endless River. Explicitly marketed as a swan song for Richard Wright, The Endless River is primarily an instrumental album pieced together from previously unreleased material largely composed by the founding member and keyboardist who passed away in 2008. Written and recorded during The Division Bell sessions, Wright's material is immediately reminiscent of that album's synth wash atmospherics with Gilmour adding in his blues descant right on cue. And that's just the thing here. It's a beautiful rendering of what made Wright such a veritable force in the band, but the music here is a formulaic response.

Gilmour's outstanding effort in 1994 was largely due to his refocusing the band's compositional framework as it had always been intended. That is, the music of Pink Floyd works best when there's equitable instrumentation. Sure, there's the solo flair and the justifiable moments of virtuosic prowess, but the band's nearly matchless power has always derived from the musical solidarity they shared against the odds of their subject matter. I'm not so cynical as to assume that The Endless River was a release purely conjured up by the marketing savvy of Gilmour, and even if that were the endgame it'd be an exercise in petty hypocrisy to dismiss the album entirely.

From a thematic standpoint, the album's source material is all too familiar. Another member lost. Another elegy. While much of that melancholy is lost in the New Age atmospheric yawn of the album, the familiarity of Wright's keyboard matched alongside Gilmour's characteristic guitar is an elegant reminder of just one of the many components that contributed to the group's success. Perhaps it's precisely the way a band like Pink Floyd needed to end, with a mournful if fragmented look at a career that had burdened itself with the same things to great success and equally as devastating losses.

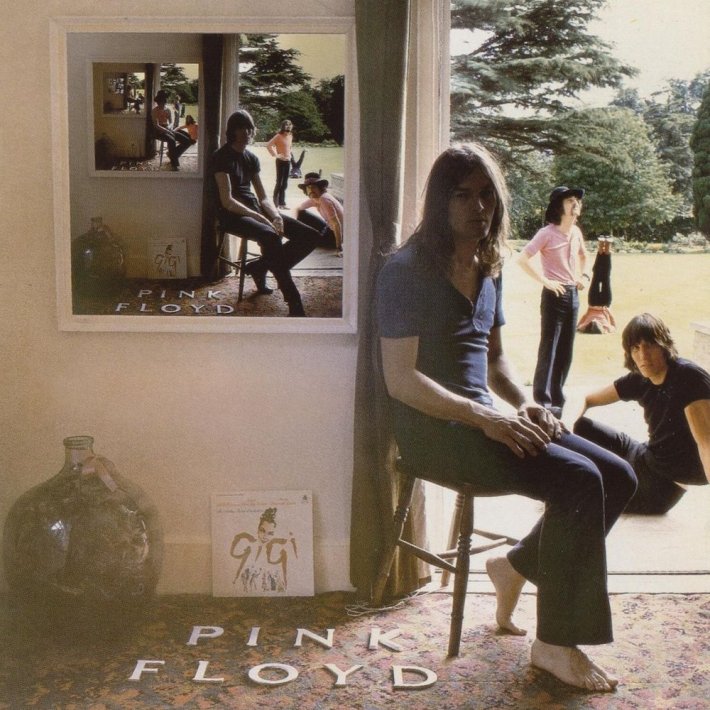

Released as a double album with the first record composed of four live tracks and the second record serving as the actual full-length, Ummagumma remains an anomalous part of Pink Floyd's discography for a number of reasons, the least of them being that the album's creation came as a result of keyboardist Richard Wright's desire to have each individual member create their own hermetic solo contribution completely removed from the other members. The "let's all make solo records" trope has proven itself to be the Russian roulette of career moves with the handful of success stories handily overshadowed by the number of well-meaning but no less terrible efforts by integral parts of a better whole.

But Ummagumma isn't a terrible record at all. If anything the album serves as a transition piece between the pop rock savvy of the band's prior release More and the full foray into the avant-garde orchestration of what would follow with 1970's Atom Heart Mother. What's most impressive with Ummagumma is that while most albums created in the midst of a band reinventing their sound skew toward the unlistenable end of the spectrum, the five songs here are enjoyable in their own right. Beginning with Wright's four-part keyboard opus "Sysyphus," Ummagumma immediately portrays an ambitious if slightly disjointed compositional makeup, with each song playing to the obvious strengths of its creator but not fully capitalizing on those strengths as the singular unit of the band working together.

Both "Grantchester Meadows" and "Several Species Of Small Furry Animals Gathered Together In A Cave and Grooving With A Pict" display the same proclivity for contrast and deceptive tenuousness that Waters would soon shape into one of the band's most defining characteristics, with the former's genteel ode to the English countryside working as a kind of mocking introduction to the frenetic electronics and groundbreaking sound manipulations of the latter. Waters' innate ability of peeling the veneer away from those societal deceptions, exposing the ugliness just below the surface, had already begun to root itself to the band's narrative thread.

"The Narrow Way" is Gilmour's three-part exploration of guitar atmospherics and the pliability of multiple overdubs, featuring the vocalist/guitarist's lyrical debut as well. While still young and likely in the throes of what had already been a relatively successful career as a musician, Gilmour's distinctive style and refusal to let his instincts take a backseat to superfluity reveal a maturity and sense of timing that even in the song's missteps provide an early picture for what would eventually develop into a definitive sound both for himself and for Pink Floyd.

Providing an end cap to Ummagumma is Mason's "The Grand Vizier's Garden Party," a three-part excursion into all manner of percussion subterfuge. Mason's oftentimes unfairly overlooked contributions to Pink Floyd are likely as such due to the fact that his style is less bombastic and explosive than that of Bonham or Moon and more subdued and measured, allowing for subtlety and, yet again, a clever sense of space to do its proper work for the tone and mood of the music. The song functions on a level of experimentation simply given the characteristic of the album's entirety, but it also highlights those traits of understated nuance that give Mason's drumming its most commanding power.

Ummagumma's placement in the Pink Floyd catalogue is less an opportunity to deride a rare overall misstep for the band and more a glimpse of how completely integral each individual member was in creating the sound that would define their existence. The album is a striking representation of those most definitive characteristics of a band whose exploration of the furthest reaches of both sound and theme would find them in the unenviably rare position of originality and stardom. Once in a place of congruence, the disjointed elements of Ummagumma would open the door to what would become Pink Floyd's at once most compelling and hauntingly unnerving creative period.

Released as a double album with the first record composed of four live tracks and the second record serving as the actual full-length, Ummagumma remains an anomalous part of Pink Floyd's discography for a number of reasons, the least of them being that the album's creation came as a result of keyboardist Richard Wright's desire to have each individual member create their own hermetic solo contribution completely removed from the other members. The "let's all make solo records" trope has proven itself to be the Russian roulette of career moves with the handful of success stories handily overshadowed by the number of well-meaning but no less terrible efforts by integral parts of a better whole.

But Ummagumma isn't a terrible record at all. If anything the album serves as a transition piece between the pop rock savvy of the band's prior release More and the full foray into the avant-garde orchestration of what would follow with 1970's Atom Heart Mother. What's most impressive with Ummagumma is that while most albums created in the midst of a band reinventing their sound skew toward the unlistenable end of the spectrum, the five songs here are enjoyable in their own right. Beginning with Wright's four-part keyboard opus "Sysyphus," Ummagumma immediately portrays an ambitious if slightly disjointed compositional makeup, with each song playing to the obvious strengths of its creator but not fully capitalizing on those strengths as the singular unit of the band working together.

Both "Grantchester Meadows" and "Several Species Of Small Furry Animals Gathered Together In A Cave and Grooving With A Pict" display the same proclivity for contrast and deceptive tenuousness that Waters would soon shape into one of the band's most defining characteristics, with the former's genteel ode to the English countryside working as a kind of mocking introduction to the frenetic electronics and groundbreaking sound manipulations of the latter. Waters' innate ability of peeling the veneer away from those societal deceptions, exposing the ugliness just below the surface, had already begun to root itself to the band's narrative thread.

"The Narrow Way" is Gilmour's three-part exploration of guitar atmospherics and the pliability of multiple overdubs, featuring the vocalist/guitarist's lyrical debut as well. While still young and likely in the throes of what had already been a relatively successful career as a musician, Gilmour's distinctive style and refusal to let his instincts take a backseat to superfluity reveal a maturity and sense of timing that even in the song's missteps provide an early picture for what would eventually develop into a definitive sound both for himself and for Pink Floyd.

Providing an end cap to Ummagumma is Mason's "The Grand Vizier's Garden Party," a three-part excursion into all manner of percussion subterfuge. Mason's oftentimes unfairly overlooked contributions to Pink Floyd are likely as such due to the fact that his style is less bombastic and explosive than that of Bonham or Moon and more subdued and measured, allowing for subtlety and, yet again, a clever sense of space to do its proper work for the tone and mood of the music. The song functions on a level of experimentation simply given the characteristic of the album's entirety, but it also highlights those traits of understated nuance that give Mason's drumming its most commanding power.

Ummagumma's placement in the Pink Floyd catalogue is less an opportunity to deride a rare overall misstep for the band and more a glimpse of how completely integral each individual member was in creating the sound that would define their existence. The album is a striking representation of those most definitive characteristics of a band whose exploration of the furthest reaches of both sound and theme would find them in the unenviably rare position of originality and stardom. Once in a place of congruence, the disjointed elements of Ummagumma would open the door to what would become Pink Floyd's at once most compelling and hauntingly unnerving creative period.

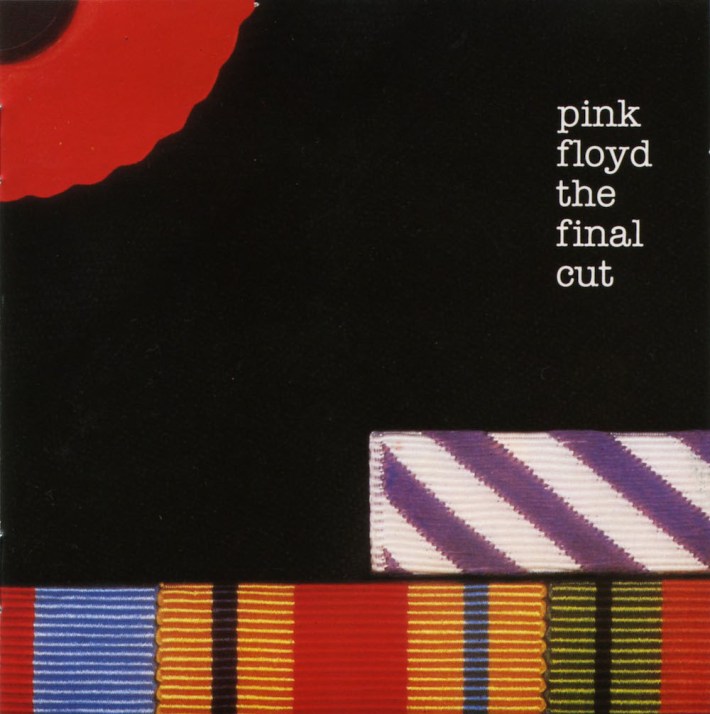

Four years after the release of what had been Waters' sole creative vision in The Final Cut, Pink Floyd's existence was at best a fragmented and embittered shadow of the force it had been only a decade earlier. The year was 1987, and though Waters had officially announced his departure from the band two years earlier having felt that Pink Floyd was exhausted creatively, the man who'd long been the primary creative force behind the band was unequivocally resistant to the band continuing on in his absence. Before chalking up that move to rock star arrogance, it's important to note the cruel irony such a situation would likely present for Waters, whose thematic obsession with the corruption and tyranny of Westernized patriarchy was now being fully manifested in the legal battle to protect the name of the band he'd spent the majority of his life so far helping to establish.

Despite the legal threats from both sides of the Pink Floyd spectrum, Gilmour along with Mason and Wright began working on what would eventually become A Momentary Lapse Of Reason. Mired in the same familiar and somewhat clichéd nuance of a band in the throes of nearly supernatural stardom attempting to work together as a singular creative force, Pink Floyd's remaining members created an excellent rock and roll record with A Momentary Lapse Of Reason, albeit one glaringly absent the sneering cynicism and epic vision of Waters. It's not that the album fails because of the void left by Waters, but that its relationship to the rest of Pink Floyd's catalogue is obviously one wholly removed from the central themes both musically and lyrically established by the band up to that point.

Recorded primarily on Gilmour's houseboat Astoria, the number of musicians credited on the album would easily rival a small orchestra -- a fairly new and somewhat overwrought departure for a band that had up to that point been able to capture the epic scale of its production using its primary members and a handful of other studio musicians. For legal reasons, Wright's own official status as a member of Pink Floyd would be relegated to studio musician, with his presence likely serving more as a legal safety net than as a crucial component to the album's creation. Even Mason's own contributions to the album were minimal simply due to the fact that the drummer had been somewhat out of practice. Much like The Final Cut had found Waters essentially creating a solo record masking itself as a new Pink Floyd album, Gilmour would do the same just four years later with the ten tracks on A Momentary Lapse of Reason.

That isn't to say that the album is lacking in terms of Gilmour's distinctive lonesome blues sound as the guitar solo on "On The Turning Away" is easily one of his finest. Though the absence of the band's characteristically theme-focused creative vision might seem as offering less of a distraction, that lack of congruence works against the album as a whole, despite the handful of outstanding individual tracks. "Yet Another Movie" along with its complementary instrumental track "Round And Around" most closely resembles those progressive orchestration techniques from Pink Floyd's mid-'70s output. Conversely, the hugely successful "Learning To Fly" fully taps into the razor sharp slickness of '80s production at its glossiest.

Gilmour's foray into the political disenchantment of his former bandmate on the song "The Dogs Of War" succeeds in so much that it underscores the guitarist's penchant for composing songs in such a way that builds on a melodic foundation and into a climactic lead out. While the song's bleak lyrical suggestions are in line with what the band had capitalized on over the bulk of their career in the wake of Barrett's departure, it and the album as a whole lacks the sneering cynicism of Waters. As a collection of excellent David Gilmour songs, A Momentary Lapse Of Reason works on nearly every level. As a Pink Floyd album, it shows the delicate but no less powerful force that came with all four musicians working in solidarity.

Much like Ummagumma, the album's faults come in the form of its fragmentation. Both Gilmour and Waters managed to produce outstanding solo work in their own right of course, but the Pink Floyd sound is not one easily patched together, much less in the midst of ego-stroking and legal caterwauling. That said, the album is impressive as a collection of rock songs from the man who, along with Waters, had created an entire world balancing itself just between the utter darkness and ethereal light just as the edges of the world it inhabited.

Four years after the release of what had been Waters' sole creative vision in The Final Cut, Pink Floyd's existence was at best a fragmented and embittered shadow of the force it had been only a decade earlier. The year was 1987, and though Waters had officially announced his departure from the band two years earlier having felt that Pink Floyd was exhausted creatively, the man who'd long been the primary creative force behind the band was unequivocally resistant to the band continuing on in his absence. Before chalking up that move to rock star arrogance, it's important to note the cruel irony such a situation would likely present for Waters, whose thematic obsession with the corruption and tyranny of Westernized patriarchy was now being fully manifested in the legal battle to protect the name of the band he'd spent the majority of his life so far helping to establish.

Despite the legal threats from both sides of the Pink Floyd spectrum, Gilmour along with Mason and Wright began working on what would eventually become A Momentary Lapse Of Reason. Mired in the same familiar and somewhat clichéd nuance of a band in the throes of nearly supernatural stardom attempting to work together as a singular creative force, Pink Floyd's remaining members created an excellent rock and roll record with A Momentary Lapse Of Reason, albeit one glaringly absent the sneering cynicism and epic vision of Waters. It's not that the album fails because of the void left by Waters, but that its relationship to the rest of Pink Floyd's catalogue is obviously one wholly removed from the central themes both musically and lyrically established by the band up to that point.

Recorded primarily on Gilmour's houseboat Astoria, the number of musicians credited on the album would easily rival a small orchestra -- a fairly new and somewhat overwrought departure for a band that had up to that point been able to capture the epic scale of its production using its primary members and a handful of other studio musicians. For legal reasons, Wright's own official status as a member of Pink Floyd would be relegated to studio musician, with his presence likely serving more as a legal safety net than as a crucial component to the album's creation. Even Mason's own contributions to the album were minimal simply due to the fact that the drummer had been somewhat out of practice. Much like The Final Cut had found Waters essentially creating a solo record masking itself as a new Pink Floyd album, Gilmour would do the same just four years later with the ten tracks on A Momentary Lapse of Reason.

That isn't to say that the album is lacking in terms of Gilmour's distinctive lonesome blues sound as the guitar solo on "On The Turning Away" is easily one of his finest. Though the absence of the band's characteristically theme-focused creative vision might seem as offering less of a distraction, that lack of congruence works against the album as a whole, despite the handful of outstanding individual tracks. "Yet Another Movie" along with its complementary instrumental track "Round And Around" most closely resembles those progressive orchestration techniques from Pink Floyd's mid-'70s output. Conversely, the hugely successful "Learning To Fly" fully taps into the razor sharp slickness of '80s production at its glossiest.

Gilmour's foray into the political disenchantment of his former bandmate on the song "The Dogs Of War" succeeds in so much that it underscores the guitarist's penchant for composing songs in such a way that builds on a melodic foundation and into a climactic lead out. While the song's bleak lyrical suggestions are in line with what the band had capitalized on over the bulk of their career in the wake of Barrett's departure, it and the album as a whole lacks the sneering cynicism of Waters. As a collection of excellent David Gilmour songs, A Momentary Lapse Of Reason works on nearly every level. As a Pink Floyd album, it shows the delicate but no less powerful force that came with all four musicians working in solidarity.

Much like Ummagumma, the album's faults come in the form of its fragmentation. Both Gilmour and Waters managed to produce outstanding solo work in their own right of course, but the Pink Floyd sound is not one easily patched together, much less in the midst of ego-stroking and legal caterwauling. That said, the album is impressive as a collection of rock songs from the man who, along with Waters, had created an entire world balancing itself just between the utter darkness and ethereal light just as the edges of the world it inhabited.

In which Pink Floyd goes metal (at least a little). Released just a few months before Ummagumma, More was a definitive move away from the primarily psychedelic sound of the band's first two albums. The band's first venture into film soundtracking, More is the sound of a band purging the angst of what had undoubtedly been an unusually trying and even tragic beginning. The album was also the first to feature Gilmour as the sole lead vocalist -- a characteristic that would not be repeated until nearly twenty years later with 1987's A Momentary Lapse Of Reason. While the psychedelic expositions of the band's first two releases are still present here (see opener "Cirrus Minor" for example), they became more of a backdrop to the central melodies and hook-friendly compositions of songs like "The Nile Song" and "Ibiza Bar" -- both of which are two of the heaviest songs Pink Floyd ever put to tape.

After the hallucinatory ease of opener "Cirrus Minor," More quickly takes shape as the riff-centered album it is with "The Nile Song" and its unhinged cyclical chord progressions paired alongside those atypically abrasive vocal stylizations of Gilmour. Interestingly enough, the normally muted and husk-tinged vocals of the guitarist took on those howls and gravel-throated traits of the blues musicians who'd long been informing his instrumentations. This same trait is heard on the nearly as heavy sounding "Ibiza Bar" and its more straightforward blues-rock aesthetic. The stylizations of these two songs in particular are noteworthy for the likes of those bands, particularly those in America, of the mid- to late-1970s era of hard rock.

Much of More still contains the pastoral balladry that Waters utilized both for its disarming characteristics as well as the contrasts presented to the more visceral sounds being created. "Crying Song" is the album's primary example of this kind of folk-infused psychedelia as Gilmour's vocals float just above the surface of Wright's vibraphone and Waters' subdued bass line and Mason's minimal use of the snare drum. The disparity between songs on More gives the album a similar sequence to A Momentary Lapse of Reason with regards to each track serving less as complement to the whole and more as wholly individual and separate compositions.

More or less an apt musical precursor to the isolated compositional structure of Ummagumma, More capitalizes on the experimentation of the band's more psychedelic beginnings and the progressive experimentation and sound manipulation that would be fully realized in the band's later material. Transitions are difficult for any band, especially one still seemingly mired in the recovery of losing what was likely its most creative mind. More's tendency to parallel the rock and roll stylizations of Pink Floyd's late-'60s contemporaries is obvious, yet in such a way that speaks to the band's seemingly instinctive predisposition to never let the music stay grounded for too long.

The most impressive tracks on More are its six instrumentals. An abnormally large number of instrumentals even by Pink Floyd's standards, each song demonstrates the incredible depth of the band's multifaceted and virtually endless musical repertoire, whether in the Mason/Wright penned electric jazz "Up The Khyber" or the hypnotic drone of "Main Theme." The eerie ambiance of "Quicksilver," with its use of multi-layered soundscapes grounded by Wright's characteristic keyboard accents, can be seen as an early indication of the band's impending change in direction to the moody rhythmic pulses on The Dark Side Of The Moon.

An important note regarding More is that the album was Pink Floyd's first to be entirely produced by the band itself. It's reasonable to assume that having fully removed Barrett from the band and separated themselves from a potentially creatively constricting producer, the band members gravitated to the most extreme aspects of their individual desires as musicians. From a motivational perspective, it's difficult to imagine the members wanting to continue on in their previous creative direction as it was one rooted almost exclusively to the psychedelic sensibilities of their newly former band mate and friend whose absence would eventually find its way into virtually every aspect of the band's creative psyche.

More is especially remarkable in that it shows both the band's tendency for experimentation and the avant-garde as well as Pink Floyd's uncanny ability at marrying those sonic conceptualizations to catchy hooks and foundational melodies. The album also showcases the band's improvisational propensities, with songs like "More Blues" betraying that sense of free-form and unhinged vulnerability the band would later develop on a grander scale both thematically and musically. More is a bit of a testament to precisely what it is that would definitively set Pink Floyd apart from virtually all other rock and roll bands, only instead of those intricate parts working in near perfect machination they are splayed out and separated into their individual parts. Even with those parts not yet working in synchronicity, the fact that More still works as well as it does is further proof of the incredible creative command of those musicians behind its creation.

In which Pink Floyd goes metal (at least a little). Released just a few months before Ummagumma, More was a definitive move away from the primarily psychedelic sound of the band's first two albums. The band's first venture into film soundtracking, More is the sound of a band purging the angst of what had undoubtedly been an unusually trying and even tragic beginning. The album was also the first to feature Gilmour as the sole lead vocalist -- a characteristic that would not be repeated until nearly twenty years later with 1987's A Momentary Lapse Of Reason. While the psychedelic expositions of the band's first two releases are still present here (see opener "Cirrus Minor" for example), they became more of a backdrop to the central melodies and hook-friendly compositions of songs like "The Nile Song" and "Ibiza Bar" -- both of which are two of the heaviest songs Pink Floyd ever put to tape.

After the hallucinatory ease of opener "Cirrus Minor," More quickly takes shape as the riff-centered album it is with "The Nile Song" and its unhinged cyclical chord progressions paired alongside those atypically abrasive vocal stylizations of Gilmour. Interestingly enough, the normally muted and husk-tinged vocals of the guitarist took on those howls and gravel-throated traits of the blues musicians who'd long been informing his instrumentations. This same trait is heard on the nearly as heavy sounding "Ibiza Bar" and its more straightforward blues-rock aesthetic. The stylizations of these two songs in particular are noteworthy for the likes of those bands, particularly those in America, of the mid- to late-1970s era of hard rock.

Much of More still contains the pastoral balladry that Waters utilized both for its disarming characteristics as well as the contrasts presented to the more visceral sounds being created. "Crying Song" is the album's primary example of this kind of folk-infused psychedelia as Gilmour's vocals float just above the surface of Wright's vibraphone and Waters' subdued bass line and Mason's minimal use of the snare drum. The disparity between songs on More gives the album a similar sequence to A Momentary Lapse of Reason with regards to each track serving less as complement to the whole and more as wholly individual and separate compositions.

More or less an apt musical precursor to the isolated compositional structure of Ummagumma, More capitalizes on the experimentation of the band's more psychedelic beginnings and the progressive experimentation and sound manipulation that would be fully realized in the band's later material. Transitions are difficult for any band, especially one still seemingly mired in the recovery of losing what was likely its most creative mind. More's tendency to parallel the rock and roll stylizations of Pink Floyd's late-'60s contemporaries is obvious, yet in such a way that speaks to the band's seemingly instinctive predisposition to never let the music stay grounded for too long.

The most impressive tracks on More are its six instrumentals. An abnormally large number of instrumentals even by Pink Floyd's standards, each song demonstrates the incredible depth of the band's multifaceted and virtually endless musical repertoire, whether in the Mason/Wright penned electric jazz "Up The Khyber" or the hypnotic drone of "Main Theme." The eerie ambiance of "Quicksilver," with its use of multi-layered soundscapes grounded by Wright's characteristic keyboard accents, can be seen as an early indication of the band's impending change in direction to the moody rhythmic pulses on The Dark Side Of The Moon.

An important note regarding More is that the album was Pink Floyd's first to be entirely produced by the band itself. It's reasonable to assume that having fully removed Barrett from the band and separated themselves from a potentially creatively constricting producer, the band members gravitated to the most extreme aspects of their individual desires as musicians. From a motivational perspective, it's difficult to imagine the members wanting to continue on in their previous creative direction as it was one rooted almost exclusively to the psychedelic sensibilities of their newly former band mate and friend whose absence would eventually find its way into virtually every aspect of the band's creative psyche.

More is especially remarkable in that it shows both the band's tendency for experimentation and the avant-garde as well as Pink Floyd's uncanny ability at marrying those sonic conceptualizations to catchy hooks and foundational melodies. The album also showcases the band's improvisational propensities, with songs like "More Blues" betraying that sense of free-form and unhinged vulnerability the band would later develop on a grander scale both thematically and musically. More is a bit of a testament to precisely what it is that would definitively set Pink Floyd apart from virtually all other rock and roll bands, only instead of those intricate parts working in near perfect machination they are splayed out and separated into their individual parts. Even with those parts not yet working in synchronicity, the fact that More still works as well as it does is further proof of the incredible creative command of those musicians behind its creation.

The only Pink Floyd full-length album to feature all five members, A Saucerful Of Secrets is at once a striking portrayal of the band's clout as one of psychedelic rock's most influential acts and yet also a cruel reminder of Barrett's mental instability and eventual removal from the band. Recorded while in the midst of various attempts by the other members to work around or even with Barrett's continually deteriorating mental state, the album's succinct cohesion is all the more astounding given the fact that the band had every reason to walk away once it became clear that their primary creative force would no longer be capable of contributing his enormous talents.

It was on this album that Gilmour made his Pink Floyd debut, joining the band more as insurance than improvement at the time in December, 1967. A school friend of Barrett's, Gilmour's addition provided the stability needed for the band to at least write and record the new material that would become A Saucerful Of Secrets, though no one could have imagined where the story would go from there. The stories of Barrett's aberrant behavior have been well documented enough to the point that the severity of its reality for both the band and the musician's family members has been largely overlooked.

Several songs recorded both for this album as well as the band's debut were either left off both releases or included on differing versions for UK and US audiences or on the various number of compilations released since. Of the seven songs featured on A Saucerful Of Secrets, Barrett appears on three, with a songwriting credit on only one -- album closer "Jugband Blues." Nostalgic romanticizing aside, the album's distinction as Pink Floyd's last hurrah of sorts with all members represented is noteworthy primarily because it signals a shift for the band both emotionally and musically -- a move invariably tied to the band's own eerie similarities as a collective in distancing themselves from comparison.

Opening with "Let There Be More Light," A Saucerful Of Secrets still holds strongly to the ethereal nature of its predecessor, only now the stratosphere of the music was grounded somewhat by Waters' own astuteness as a songwriter more concerned with the tangibility of paranoia than with the abstract notion of its effects on him personally. From its simplistic but exacting bass line opening to the full bloom of Gilmour's lead out solo, "Let There Be More Light" sets the tone for the album's comparatively more linear musical thread than the erratic but no less brilliantly composed songs of the band's debut.

The Wright-penned "Remember A Day" features Barrett on slide guitar and, despite the little fanfare given to it, is one of the finest songs from the band's early days. Wright's bari-tenor vocals offer an eerily complementary nuance to the hiccupped percussion from Mason and the at times jarring slide guitar from Barrett. The album's most likely recognizable track is the hypnotically serpentine "Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun" -- a five-and-a-half minute digression into psychedelic minimalism and the earliest indicator of what would become Pink Floyd's balance between paranoid psychosis and popular culture.

Though the subject of Barrett's contribution to the song alongside Gilmour will likely remain eternally scrutinized, both musicians take a backseat to the combination of Mason, Waters, and most of all, Wright in "Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun" Wright's proclivity for texturing a song without saturating its tone with unnecessary meanderings was such an immense and crucial part of what defined Pink Floyd's sound from the very beginning and, interestingly enough, one of the very few characteristics that remained largely unhindered throughout the band's few evolutionary changes in sound.

The seemingly endless number of permutations of the song give due credit both to Waters' musicianship as well as the band's versatility and improvisational instinct. Shoehorned with Wright's spooky Farfisa organ and the rhythmic hypnosis of Mason's timpani percussion, Waters' vocals undoubtedly made quick work of any speculation that Pink Floyd would falter in the wake of its abrupt and largely unwanted lineup change. A clear depiction of every powerful component of Pink Floyd's sound and dynamic as a group, "Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun" is arguably the definitive song from this era of the group's existence and a hauntingly beautiful picture of the band's most successful and powerful formula of less is more.

Featuring Gilmour, Mason, and Wright on vocals "Corporal Clegg" plays primarily to the psychedelic leanings of Piper with layered voiceovers and bizarre instrumentation taking the spotlight of each verse leading into the by-the-numbers '60s-era vocal harmonization of the chorus. It's not to say the song is meritless in its own right but rather that it echoes the song structure typical of those psychedelic and experimental contemporaries of Pink Floyd. Even with the obvious influence or mirroring of the pop music context of the time, Gilmour's guitar work cleverly incorporating the relatively few pedal options at the time alongside the deliberately ridiculous kazoo-lead bridge give the song the characteristic of being one only Pink Floyd could write.

The album's title track is a masterful achievement both from a sound technology perspective and for the band members themselves as the instrumental's nearly twelve minutes plays in such a way as to suggest a long-rooted understanding between each musicians rather than the reality of this being their first creative collaboration with all members (excluding Barrett) credited as songwriters. For all its extremity and avant-garde gesticulations, the album's title track is the first glimpse of how rewarding the band's congruency could be both for themselves as artists and the listening audience as well.

Closing out A Saucerful Of Secrets is the eerily appropriate "Jugband Blues," seeming like another one of Barrett's harmless if slightly off kilter and absurd pop songs. Listening to the song's lyrics and considering the context of when Barrett would have likely written them, and "Jugband Blues" becomes something of a ghost in the Pink Floyd catalogue, standing at the tail end of an album that while signaling a farewell to the troubled musician could not every fully rid themselves of his presence within virtually every aspect of the band's success and eventual twilight.

Barrett's typically abstract if sparsely referenced lyrical mode is somewhat muted on "Jugband Blues," making a substantially well-suited argument that lines such as "I'm awfully considerate of you to think of me here / And I'm much obliged to you for making it clear / That I'm not here" are little more than directed statements at his band mates. The song also continues the at the time ever present indication that Barrett had most probably lost a general sense of reality and was entering a full state of psychosis with lines like " And I'm wondering who could be writing this song" offering at least minimal proof of the same emotional detachment that had plagued both Barrett himself and his band mates and friends.

The song would be the last Barrett would write for Pink Floyd and even as the album's most disjointed track from a comparative standpoint, "Jugband Blues" is difficult to listen to without considering the weight of its words both on the fragmented mind of its creator and the conflicted band mates and friends who felt compelled to keep the track on the album. Barrett's distinguishing vocals are as disarming as ever, making the track that much more unsettling in the larger picture surrounding its creation. Whatever childlike naivety and brilliance may have overcome the adult mind of Barrett, "Jugband Blues" remains a captivating if tragic end piece both for the first permutation of Pink Floyd's ever evolving sound and for the man who'd lost himself along the way, far too soon.

The only Pink Floyd full-length album to feature all five members, A Saucerful Of Secrets is at once a striking portrayal of the band's clout as one of psychedelic rock's most influential acts and yet also a cruel reminder of Barrett's mental instability and eventual removal from the band. Recorded while in the midst of various attempts by the other members to work around or even with Barrett's continually deteriorating mental state, the album's succinct cohesion is all the more astounding given the fact that the band had every reason to walk away once it became clear that their primary creative force would no longer be capable of contributing his enormous talents.

It was on this album that Gilmour made his Pink Floyd debut, joining the band more as insurance than improvement at the time in December, 1967. A school friend of Barrett's, Gilmour's addition provided the stability needed for the band to at least write and record the new material that would become A Saucerful Of Secrets, though no one could have imagined where the story would go from there. The stories of Barrett's aberrant behavior have been well documented enough to the point that the severity of its reality for both the band and the musician's family members has been largely overlooked.

Several songs recorded both for this album as well as the band's debut were either left off both releases or included on differing versions for UK and US audiences or on the various number of compilations released since. Of the seven songs featured on A Saucerful Of Secrets, Barrett appears on three, with a songwriting credit on only one -- album closer "Jugband Blues." Nostalgic romanticizing aside, the album's distinction as Pink Floyd's last hurrah of sorts with all members represented is noteworthy primarily because it signals a shift for the band both emotionally and musically -- a move invariably tied to the band's own eerie similarities as a collective in distancing themselves from comparison.

Opening with "Let There Be More Light," A Saucerful Of Secrets still holds strongly to the ethereal nature of its predecessor, only now the stratosphere of the music was grounded somewhat by Waters' own astuteness as a songwriter more concerned with the tangibility of paranoia than with the abstract notion of its effects on him personally. From its simplistic but exacting bass line opening to the full bloom of Gilmour's lead out solo, "Let There Be More Light" sets the tone for the album's comparatively more linear musical thread than the erratic but no less brilliantly composed songs of the band's debut.

The Wright-penned "Remember A Day" features Barrett on slide guitar and, despite the little fanfare given to it, is one of the finest songs from the band's early days. Wright's bari-tenor vocals offer an eerily complementary nuance to the hiccupped percussion from Mason and the at times jarring slide guitar from Barrett. The album's most likely recognizable track is the hypnotically serpentine "Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun" -- a five-and-a-half minute digression into psychedelic minimalism and the earliest indicator of what would become Pink Floyd's balance between paranoid psychosis and popular culture.

Though the subject of Barrett's contribution to the song alongside Gilmour will likely remain eternally scrutinized, both musicians take a backseat to the combination of Mason, Waters, and most of all, Wright in "Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun" Wright's proclivity for texturing a song without saturating its tone with unnecessary meanderings was such an immense and crucial part of what defined Pink Floyd's sound from the very beginning and, interestingly enough, one of the very few characteristics that remained largely unhindered throughout the band's few evolutionary changes in sound.

The seemingly endless number of permutations of the song give due credit both to Waters' musicianship as well as the band's versatility and improvisational instinct. Shoehorned with Wright's spooky Farfisa organ and the rhythmic hypnosis of Mason's timpani percussion, Waters' vocals undoubtedly made quick work of any speculation that Pink Floyd would falter in the wake of its abrupt and largely unwanted lineup change. A clear depiction of every powerful component of Pink Floyd's sound and dynamic as a group, "Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun" is arguably the definitive song from this era of the group's existence and a hauntingly beautiful picture of the band's most successful and powerful formula of less is more.

Featuring Gilmour, Mason, and Wright on vocals "Corporal Clegg" plays primarily to the psychedelic leanings of Piper with layered voiceovers and bizarre instrumentation taking the spotlight of each verse leading into the by-the-numbers '60s-era vocal harmonization of the chorus. It's not to say the song is meritless in its own right but rather that it echoes the song structure typical of those psychedelic and experimental contemporaries of Pink Floyd. Even with the obvious influence or mirroring of the pop music context of the time, Gilmour's guitar work cleverly incorporating the relatively few pedal options at the time alongside the deliberately ridiculous kazoo-lead bridge give the song the characteristic of being one only Pink Floyd could write.

The album's title track is a masterful achievement both from a sound technology perspective and for the band members themselves as the instrumental's nearly twelve minutes plays in such a way as to suggest a long-rooted understanding between each musicians rather than the reality of this being their first creative collaboration with all members (excluding Barrett) credited as songwriters. For all its extremity and avant-garde gesticulations, the album's title track is the first glimpse of how rewarding the band's congruency could be both for themselves as artists and the listening audience as well.

Closing out A Saucerful Of Secrets is the eerily appropriate "Jugband Blues," seeming like another one of Barrett's harmless if slightly off kilter and absurd pop songs. Listening to the song's lyrics and considering the context of when Barrett would have likely written them, and "Jugband Blues" becomes something of a ghost in the Pink Floyd catalogue, standing at the tail end of an album that while signaling a farewell to the troubled musician could not every fully rid themselves of his presence within virtually every aspect of the band's success and eventual twilight.

Barrett's typically abstract if sparsely referenced lyrical mode is somewhat muted on "Jugband Blues," making a substantially well-suited argument that lines such as "I'm awfully considerate of you to think of me here / And I'm much obliged to you for making it clear / That I'm not here" are little more than directed statements at his band mates. The song also continues the at the time ever present indication that Barrett had most probably lost a general sense of reality and was entering a full state of psychosis with lines like " And I'm wondering who could be writing this song" offering at least minimal proof of the same emotional detachment that had plagued both Barrett himself and his band mates and friends.

The song would be the last Barrett would write for Pink Floyd and even as the album's most disjointed track from a comparative standpoint, "Jugband Blues" is difficult to listen to without considering the weight of its words both on the fragmented mind of its creator and the conflicted band mates and friends who felt compelled to keep the track on the album. Barrett's distinguishing vocals are as disarming as ever, making the track that much more unsettling in the larger picture surrounding its creation. Whatever childlike naivety and brilliance may have overcome the adult mind of Barrett, "Jugband Blues" remains a captivating if tragic end piece both for the first permutation of Pink Floyd's ever evolving sound and for the man who'd lost himself along the way, far too soon.

To understand the oddity that is Obscured By Clouds you have to understand the context of the album's creation and subsequent rushed recording process. Having had a considerable amount of experience and success in the creation of soundtracks by this time in their career, the band agreed to write yet another one, this time for the 1972 Barbet Schroeder film La Vallée. Despite being less than a year removed from the band's defining release The Dark Side Of The Moon, Obscured By Clouds bears little if any resemblance to that album. Given the fact that the band actually took a brief break from recording that album to write and record Obscured By Clouds makes the story and, more importantly, the music of the album that much more interesting.

The album's distinction from the rest of the band's catalogue is primarily found in the fanfare and generally upbeat nature of the music, with the somewhat contemptuous lyrical content serving as the only commonality with their other material. As their seventh studio album, Obscured By Clouds is an apt if slightly uncharacteristic midpoint for Pink Floyd's catalogue. Much like More or A Momentary Lapse Of Reason, the album's songwriting credits are indicative of the musical direction, as Gilmour helmed the lion's share of writing duties as opposed to the responsibility being solely on the shoulders of Waters.

Another similarity with the previously mentioned soundtrack More is the inclusion of several instrumentals, yet instead of providing a framework for the avant-garde experimentation of that album, these instrumentals serve more as complementary compositions than stand-alone tracks. Especially present is the band's then fully developed use of synthesizer and electronic instrumentation, as on the album's opening title track featuring Wright's characteristic atmospherics by way of an EMS VCS 3 paired alongside Mason's electronic drumming and the blues wail of Gilmour's guitar. The disparity between the pulsing churn of this song and the band's previous album Meddle is striking if only for the fact that it provides a clear cut line of departure from that album's ethereal free-form tendencies.

Considering the fact that Pink Floyd had already written and begun recording a large portion of The Dark Side Of The Moon when the opportunity to create this soundtrack presented itself, the contrasts between the two albums become that much more fascinating and, perhaps more importantly, a testament to their songwriting versatility. The incalculable success of The Dark Side Of The Moon almost immediately overshadowed any kind of recognition for Obscured By Clouds, and while the former is unquestionably a greater achievement for the band, the latter has over time established itself as an overlooked gem of straightforward rock and roll from a band who'd largely built their career from going brilliantly off script.

That Pink Floyd could write an album of fairly straightforward pop rock songs in 1972 is nothing overtly impressive as the band had shown itself a versatile force with releases like More being followed up just a year later with the inherently different Atom Heart Mother. That the band could write these ten songs at the midpoint of writing the album that would indisputably change the course of their creativity and essentially bridge the gap between experimentation in music and mainstream audiences is absolutely astounding. Pink Floyd's clout as a veritable force in rock and roll would undoubtedly be assured with the release of The Dark Side Of The Moon, but their sheer talents and adaptability as songwriters came quietly in the months prior with the release of Obscured By Clouds.

Gilmour's signature pop sensibilities alongside those tendencies for compositional texturing from the likes of Waters and Wright are the formula for success on the ten tracks of Obscured By Clouds. Though Gilmour's solo work and that of Pink Floyd's Waters-less days would find the guitarist/vocalist taking on a similar approach, the difference here is still the same congruency that would find the band at their most creatively and commercially successful. Even the Waters-penned (and as such characteristically dark) song "Free Four" moves with an affable tempo contrasting the lyrics to the point of overshadowing their autobiographical nature concerning Waters' father -- a narrative thread that would be fully and hauntingly realized in the musician's final years with the band.

In the alternate universe that is the completely radio-friendly Pink Floyd of Obscured By Clouds, tracks such as "The Gold It's In The ..." with its upbeat tempo and care free lyrical narrative play with a strange and inviting ease as opposed to the deliberately abrasive trademark of the band's other material. While this song as well as the near positivist "Wot's ... Uh The Deal?" might sound like the categorical 1970s venture into rock balladry by any other band, the context of its creation as well as the comparison to the band's entire catalogue suggests that perhaps this album itself was the apex of Pink Floyd's experimentation with the rest of their material simply echoing the band's own singular form of creative normalcy.

Though the band had nothing to prove in the way of their diversity and obviously could not have had any clue as to the overwhelming success and universal acclaim that would soon be at their door, Obscured by Clouds works in such a way as to suggest that if Pink Floyd had wished to creatively align themselves with the glut of 1970s blues-tinged rock and roll, they could have done so quite successfully even outside the spectrum of their reputation for experimentation and the near mythology of their beginnings with Barrett. In retrospect the album now stands as an eerily hopeful creative farewell just before the era that would find the band fully enveloping their music in an unforgivingly dark brilliance.

To understand the oddity that is Obscured By Clouds you have to understand the context of the album's creation and subsequent rushed recording process. Having had a considerable amount of experience and success in the creation of soundtracks by this time in their career, the band agreed to write yet another one, this time for the 1972 Barbet Schroeder film La Vallée. Despite being less than a year removed from the band's defining release The Dark Side Of The Moon, Obscured By Clouds bears little if any resemblance to that album. Given the fact that the band actually took a brief break from recording that album to write and record Obscured By Clouds makes the story and, more importantly, the music of the album that much more interesting.

The album's distinction from the rest of the band's catalogue is primarily found in the fanfare and generally upbeat nature of the music, with the somewhat contemptuous lyrical content serving as the only commonality with their other material. As their seventh studio album, Obscured By Clouds is an apt if slightly uncharacteristic midpoint for Pink Floyd's catalogue. Much like More or A Momentary Lapse Of Reason, the album's songwriting credits are indicative of the musical direction, as Gilmour helmed the lion's share of writing duties as opposed to the responsibility being solely on the shoulders of Waters.

Another similarity with the previously mentioned soundtrack More is the inclusion of several instrumentals, yet instead of providing a framework for the avant-garde experimentation of that album, these instrumentals serve more as complementary compositions than stand-alone tracks. Especially present is the band's then fully developed use of synthesizer and electronic instrumentation, as on the album's opening title track featuring Wright's characteristic atmospherics by way of an EMS VCS 3 paired alongside Mason's electronic drumming and the blues wail of Gilmour's guitar. The disparity between the pulsing churn of this song and the band's previous album Meddle is striking if only for the fact that it provides a clear cut line of departure from that album's ethereal free-form tendencies.

Considering the fact that Pink Floyd had already written and begun recording a large portion of The Dark Side Of The Moon when the opportunity to create this soundtrack presented itself, the contrasts between the two albums become that much more fascinating and, perhaps more importantly, a testament to their songwriting versatility. The incalculable success of The Dark Side Of The Moon almost immediately overshadowed any kind of recognition for Obscured By Clouds, and while the former is unquestionably a greater achievement for the band, the latter has over time established itself as an overlooked gem of straightforward rock and roll from a band who'd largely built their career from going brilliantly off script.

That Pink Floyd could write an album of fairly straightforward pop rock songs in 1972 is nothing overtly impressive as the band had shown itself a versatile force with releases like More being followed up just a year later with the inherently different Atom Heart Mother. That the band could write these ten songs at the midpoint of writing the album that would indisputably change the course of their creativity and essentially bridge the gap between experimentation in music and mainstream audiences is absolutely astounding. Pink Floyd's clout as a veritable force in rock and roll would undoubtedly be assured with the release of The Dark Side Of The Moon, but their sheer talents and adaptability as songwriters came quietly in the months prior with the release of Obscured By Clouds.

Gilmour's signature pop sensibilities alongside those tendencies for compositional texturing from the likes of Waters and Wright are the formula for success on the ten tracks of Obscured By Clouds. Though Gilmour's solo work and that of Pink Floyd's Waters-less days would find the guitarist/vocalist taking on a similar approach, the difference here is still the same congruency that would find the band at their most creatively and commercially successful. Even the Waters-penned (and as such characteristically dark) song "Free Four" moves with an affable tempo contrasting the lyrics to the point of overshadowing their autobiographical nature concerning Waters' father -- a narrative thread that would be fully and hauntingly realized in the musician's final years with the band.

In the alternate universe that is the completely radio-friendly Pink Floyd of Obscured By Clouds, tracks such as "The Gold It's In The ..." with its upbeat tempo and care free lyrical narrative play with a strange and inviting ease as opposed to the deliberately abrasive trademark of the band's other material. While this song as well as the near positivist "Wot's ... Uh The Deal?" might sound like the categorical 1970s venture into rock balladry by any other band, the context of its creation as well as the comparison to the band's entire catalogue suggests that perhaps this album itself was the apex of Pink Floyd's experimentation with the rest of their material simply echoing the band's own singular form of creative normalcy.

Though the band had nothing to prove in the way of their diversity and obviously could not have had any clue as to the overwhelming success and universal acclaim that would soon be at their door, Obscured by Clouds works in such a way as to suggest that if Pink Floyd had wished to creatively align themselves with the glut of 1970s blues-tinged rock and roll, they could have done so quite successfully even outside the spectrum of their reputation for experimentation and the near mythology of their beginnings with Barrett. In retrospect the album now stands as an eerily hopeful creative farewell just before the era that would find the band fully enveloping their music in an unforgivingly dark brilliance.

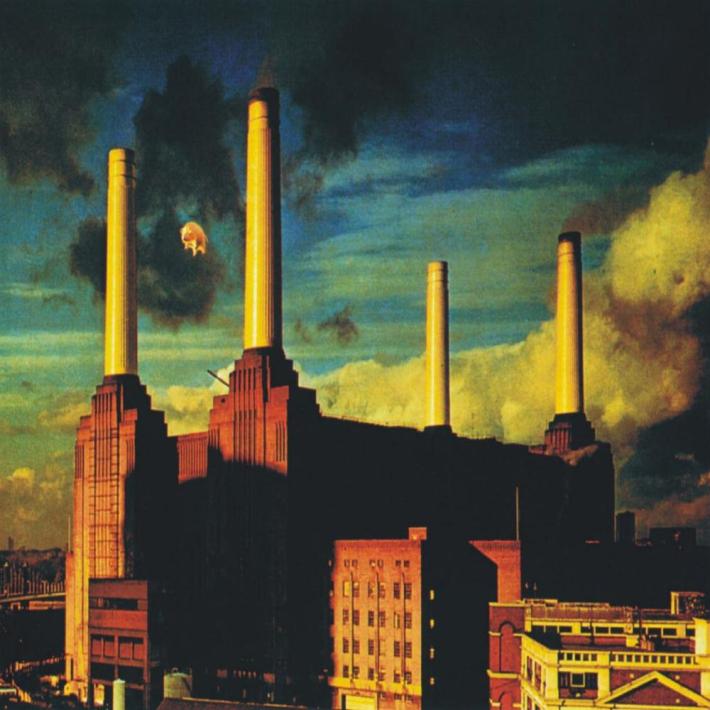

Even in the aftermath of the various lawsuits and threats of lawsuits concerning, among other things, floating pigs, band names, members as non-members, and more, the distant memory of Roger Waters as a member of Pink Floyd seemed no less strange to the band's fans, and presumably to the remaining band members themselves. Released in 1994, the band's fourteenth studio album The Division Bell now renders a sobering look at the whole of Pink Floyd's existence as a band that, even in their obvious twilight, were still fully capable of creating powerfully compelling music. The eleven songs here are less an exercise for Gilmour in flexing his creative muscle outside the scope of Waters' creative vision and more a collaborative creative effort with Pink Floyd as the sole focus.

Sidestepping the band's previous direction of avoiding any overarching themes with A Momentary Lapse Of Reason, The Division Bell found its primary writers, Gilmour and Wright, exploring the concept of communication and its inevitable tendency toward entropy or, more fittingly for Pink Floyd, disillusionment. Though overly long, the album has aged considerably well in the twenty years since its creation and much more so than its predecessor where distraction and creative misdirection had allowed the music to falter. Though initially and unfairly scrutinized, the inclusion of Gilmour's then-wife Polly Samson as a co-lyricist has since proven itself a wise move on the part of the vocalist/guitarist in offering a multifaceted perspective in place of a tired and by that time largely irrelevant formula.

The Division Bell offers an interesting perspective on those most powerful components of Pink Floyd's music and why the thematic focus and narrative thread of their music played such a vital role in their creative output. With Waters gone, the album is understandably devoid of the trademark wit and dark sarcasm of the bassist/vocalist, but the welcomed absence of legal and personal distraction for Gilmour had an undeniable positive impact on creating a sound for The Division Bell that was unmistakably Pink Floyd. Though now not technically the band's swansong, it's difficult to see the album as anything less than a final display of rock and roll greatness for a band who'd made their struggle with that very identity the core of their creativity for so long.

Especially with regards to the first four tracks, The Division Bell takes on Pink Floyd's most notable characteristics as atmospherics meet melody in the same synchronized fluidity that allowed albums such as Meddle and Wish You Were Here to wield their own singularly powerful sound. The instrumental "Marooned" stands out primarily as a song that sounds as much like Pink Floyd as anything on their mid-'70s releases. The song roots itself to Gilmour's familiar lonesome melodic guitar descants threading themselves through the trademark mood setting and foundation of Mason's drum work and the invaluable Wright's keyboard deviations.

Initially dismissed by a number of critics, The Division Bell is the representation of the best Pink Floyd could possibly be in the absence of now two of its original and primary creative forces. The album is not without its missteps such as the lyrically heavy-handed "A Great Day For Freedom" and its not so vague references to the band being liberated from Waters (despite Gilmour's vehement denial to the contrary). As the last song to feature Wright on vocals and the only Pink Floyd song past The Dark Side Of The Moon not to feature either Waters or Gilmour as songwriter, the new age gloss of "Wearing The Inside Out" too often detracts from a melody line that might otherwise fit perfectly in the band's early albums.

"Take It Back" finds Gilmour in rare upbeat form with an arpeggio closely resembling the likes of U2's The Edge and lending itself much in the same way to creating a layered framework for the song's primary melodic line. The song is not especially memorable as a Pink Floyd work necessarily but certainly indicative of Gilmour's near limitless abilities as a pop rock guitarist fully capable of adapting into a variance of styles depending on what specific sound most viably served to complement the song's structure. "Coming Back To Life" is another example of this as Gilmour's penchant for well-timed crescendo into lead out solo take full and successful form, though slightly detracted by overly-slick production.

With its judicious use of sound technology and Wright's synth brilliance, "Keep Talking" closely resembles the simmering pulse of The Wall with the airy chorus of voices contrasting against the brooding churn of the music driving their melody. The song is another example of the album's success in mirroring the same compositional sentiments that had proven time and again to be Pink Floyd's most reliable creative ally. In terms of evocative post-scripts for those bands in the sunset of a career as defined by the members' public personal struggles as it was by the groundbreaking music they created, "High Hopes" is an aptly emotional end piece to The Division Bell.

As much an auditory manifestation of Gilmour's own personal life, "High Hopes" is also a somber look back both musically and lyrically at Pink Floyd's existence and the open-ended question of what paths its members took as opposed to the ones that took them regardless of individual choice. Though Waters' absence is readily apparent on The Division Bell from a creative standpoint, it also serves as a kind of sobering reminder of the fragile and often bleak introspection that defined Pink Floyd without regard to the various attempts by its individual members to avoid facing the cold reality of that dilemma. Twenty years later, The Division Bell looks strikingly different than it did upon its initial release as time has allowed these songs to offer their full if slowly realized rewards much in the same way that defined the band who created them.

Even in the aftermath of the various lawsuits and threats of lawsuits concerning, among other things, floating pigs, band names, members as non-members, and more, the distant memory of Roger Waters as a member of Pink Floyd seemed no less strange to the band's fans, and presumably to the remaining band members themselves. Released in 1994, the band's fourteenth studio album The Division Bell now renders a sobering look at the whole of Pink Floyd's existence as a band that, even in their obvious twilight, were still fully capable of creating powerfully compelling music. The eleven songs here are less an exercise for Gilmour in flexing his creative muscle outside the scope of Waters' creative vision and more a collaborative creative effort with Pink Floyd as the sole focus.

Sidestepping the band's previous direction of avoiding any overarching themes with A Momentary Lapse Of Reason, The Division Bell found its primary writers, Gilmour and Wright, exploring the concept of communication and its inevitable tendency toward entropy or, more fittingly for Pink Floyd, disillusionment. Though overly long, the album has aged considerably well in the twenty years since its creation and much more so than its predecessor where distraction and creative misdirection had allowed the music to falter. Though initially and unfairly scrutinized, the inclusion of Gilmour's then-wife Polly Samson as a co-lyricist has since proven itself a wise move on the part of the vocalist/guitarist in offering a multifaceted perspective in place of a tired and by that time largely irrelevant formula.

The Division Bell offers an interesting perspective on those most powerful components of Pink Floyd's music and why the thematic focus and narrative thread of their music played such a vital role in their creative output. With Waters gone, the album is understandably devoid of the trademark wit and dark sarcasm of the bassist/vocalist, but the welcomed absence of legal and personal distraction for Gilmour had an undeniable positive impact on creating a sound for The Division Bell that was unmistakably Pink Floyd. Though now not technically the band's swansong, it's difficult to see the album as anything less than a final display of rock and roll greatness for a band who'd made their struggle with that very identity the core of their creativity for so long.

Especially with regards to the first four tracks, The Division Bell takes on Pink Floyd's most notable characteristics as atmospherics meet melody in the same synchronized fluidity that allowed albums such as Meddle and Wish You Were Here to wield their own singularly powerful sound. The instrumental "Marooned" stands out primarily as a song that sounds as much like Pink Floyd as anything on their mid-'70s releases. The song roots itself to Gilmour's familiar lonesome melodic guitar descants threading themselves through the trademark mood setting and foundation of Mason's drum work and the invaluable Wright's keyboard deviations.

Initially dismissed by a number of critics, The Division Bell is the representation of the best Pink Floyd could possibly be in the absence of now two of its original and primary creative forces. The album is not without its missteps such as the lyrically heavy-handed "A Great Day For Freedom" and its not so vague references to the band being liberated from Waters (despite Gilmour's vehement denial to the contrary). As the last song to feature Wright on vocals and the only Pink Floyd song past The Dark Side Of The Moon not to feature either Waters or Gilmour as songwriter, the new age gloss of "Wearing The Inside Out" too often detracts from a melody line that might otherwise fit perfectly in the band's early albums.

"Take It Back" finds Gilmour in rare upbeat form with an arpeggio closely resembling the likes of U2's The Edge and lending itself much in the same way to creating a layered framework for the song's primary melodic line. The song is not especially memorable as a Pink Floyd work necessarily but certainly indicative of Gilmour's near limitless abilities as a pop rock guitarist fully capable of adapting into a variance of styles depending on what specific sound most viably served to complement the song's structure. "Coming Back To Life" is another example of this as Gilmour's penchant for well-timed crescendo into lead out solo take full and successful form, though slightly detracted by overly-slick production.

With its judicious use of sound technology and Wright's synth brilliance, "Keep Talking" closely resembles the simmering pulse of The Wall with the airy chorus of voices contrasting against the brooding churn of the music driving their melody. The song is another example of the album's success in mirroring the same compositional sentiments that had proven time and again to be Pink Floyd's most reliable creative ally. In terms of evocative post-scripts for those bands in the sunset of a career as defined by the members' public personal struggles as it was by the groundbreaking music they created, "High Hopes" is an aptly emotional end piece to The Division Bell.

As much an auditory manifestation of Gilmour's own personal life, "High Hopes" is also a somber look back both musically and lyrically at Pink Floyd's existence and the open-ended question of what paths its members took as opposed to the ones that took them regardless of individual choice. Though Waters' absence is readily apparent on The Division Bell from a creative standpoint, it also serves as a kind of sobering reminder of the fragile and often bleak introspection that defined Pink Floyd without regard to the various attempts by its individual members to avoid facing the cold reality of that dilemma. Twenty years later, The Division Bell looks strikingly different than it did upon its initial release as time has allowed these songs to offer their full if slowly realized rewards much in the same way that defined the band who created them.