Steely Dan are playing this year's Coachella, they've been sampled by everyone from Kanye to Cities Aviv, and you can hear hints of their sardonic lyrical brilliance in indie rockers ranging from the Dismemberment Plan to Destroyer to Father John Misty. But for a band that made its name puncturing the remnants of the flower-child '60s with a New York bohemianism that recalibrated the trappings of "cool," the Dan are still widely considered anything but. Judd Apatow's an admitted fan, but he still got a laugh line out of Knocked Up's Seth Rogen at their expense ("Steely Dan gargles my balls… if I ever listen to Steely Dan I want you to slice my head off with an Al Jarreau LP"). One of the funniest running-gag tirades on The Best Show is Tom Scharpling's fuming contempt for them ("If you like rock music, you can't like Steely Dan," and vice versa), even if his comedy partner Jon Wurster loves them. When the Minutemen covered "Doctor Wu" on 1984's Double Nickels On The Dime, most punks must've figured it was a goof.

Critics had the tendency to laud them, especially during the first half of their career -- Creem's Richard Cromelin called them "the best band in America" during his assessment of 1974's Pretzel Logic, and Stranded editor Greil Marcus called their "Doctor Wu" couplet "All night long, we would sing that stupid song/And every word we sang I knew was true" "two of the finest lines rock and roll has produced about itself." But that was muso-wonk nerd stuff, at least in the eyes of the decade's latter half and its zero-year punk rock rebellion; they might crack the Pazz & Jop top ten but good luck selling the louder-and-faster disciples of Lester Bangs on 'em.

But bands with cryptic lyrics, intricate music-theory-bait arrangements, and dark humor have a way of eventually growing their cult. There's definitely something kind of geek-chic about them; you could put them up there with Frank Zappa and Rush for rabid '70s-rooted prog-adjacent enthusiasms, and they even have their own fairly thorough page on pop-culture deconstruction portal TV Tropes. If that kind of association threatens to ding up your indie cred and otherwise make you uncomfortable, well, you could always just shuck the trappings and dig in to the songs themselves. There, up in their acid-penned framework, it's easier to think of them as Dylan-influenced weirdos who grew up into the lost American cousins of the UK's Angry Young Men of the late '70s. Think the similarly nasal, anxious, glibly frustrated and thoroughly postmodern Elvis Costello (who put Countdown To Ecstasy on his personal list of "500 Albums You Need" in a 2000 Vanity Fair article), or the sophisti-pop leanings of avowed fan Joe Jackson, or even legendary pub-punk oddball Ian Dury, who lauded Aja by calling it "heartwarming" and "upfull."

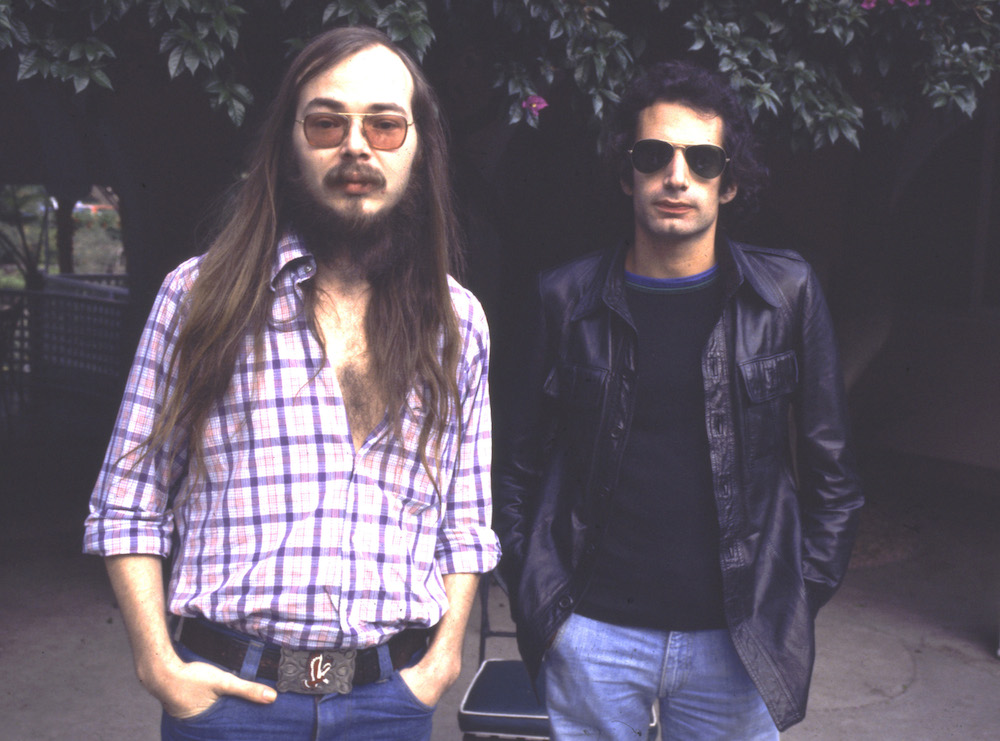

And forget the relaxed cheeriness of the context that slotted them into the yacht-rock ranks with Loggins & Messina and the Doobie Brothers -- shared sessionman personnel and L.A. neighborliness notwithstanding, Walter Becker and Donald Fagen were New York to the core, all Brill Building gone Burroughs, using the language of pop as their foot in the door to ease in creepier, more unsettling things. No amount of multi-tracked studio trickery, woodshedder scrubbed-up arrangements, or perfectionist, precise ultra-virtuoso slickness could really obscure the existential dread and hip-panic self-consciousness that made their lyrics resonate. So they piled on as much gloss as they could, stitched together all manners of hopped-up jazz and rhythm & blues permutations into the weave of their sound, and infiltrated the subconsciousness of future yuppies everywhere like some kind of Manchurian Candidate virus to make them eventually realize there's futility in optimism. Chuck Klosterman caught hell for claiming that Steely Dan were more lyrically subversive than the Sex Pistols, but at least with John Lydon scowling at you, you know just what he's saying and fast. Hear one of Steely Dan's ostensibly lighthearted hits on the classic rock airwaves -- something like "Rikki Don't Lose That Number" or "Black Friday," endlessly catchy and hummable, and deciding to buy the rest of that album and dive in -- and all of a sudden, you wind up hearing songs about creeps who screen porno flicks to teenagers or the death of a homeless addict. Oh hell -- this isn't Seals And Crofts at all. There are several ways to go through this bewildering process. Here they are.

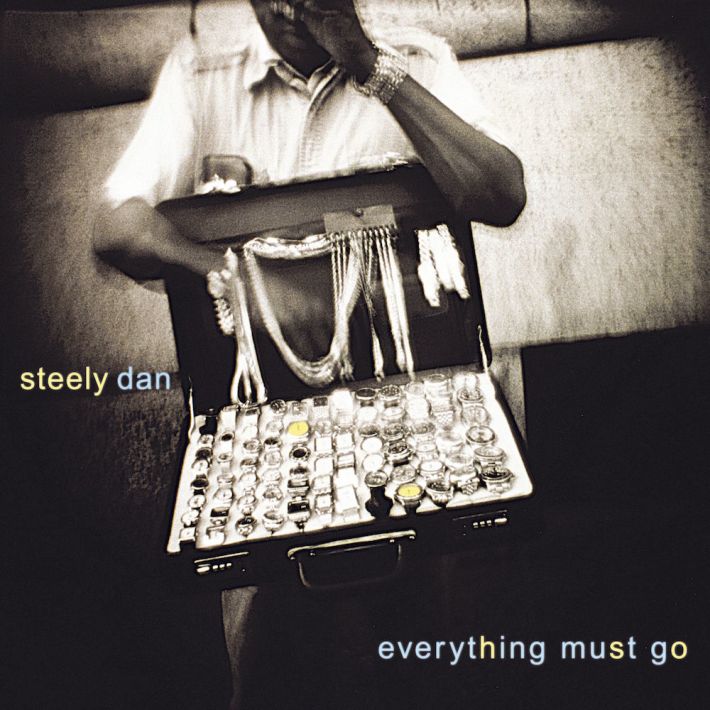

The comeback that sprung from Two Against Nature seems like a blip on the radar compared to the critical reevaluation and generational carryover that the first wave of Steely Dan's records received in its wake. And maybe you could chalk that up to said comeback resulting in all of two studio albums, the most recent one nearly a dozen years old; there are two pretty good Donald Fagen solo records in far more recent memory. As a side effect, Everything Must Go feels like an official final statement, cutting off the notion of Steely Dan as a continuing enterprise and cementing them as something more of a legacy act, a name for Becker and Fagen to operate under in the past tense while they do their own things with separate autonomy. It doesn't hurt the case that the title cut's the closing track, and bears all the signs of a metaphor for the end of a once-successful enterprise liquidating its assets.

It's an obvious, to-the-point analogy -- and that's part of the problem. Allusions that made personal specificity out of familiar themes always stood as one of the best strengths of Steely Dan's songwriting, and Everything Must Go makes the themes far more obvious than they had been at any point in the band's discography. Where it took a few listens to a song like Countdown To Ecstasy's "King Of The World" for the postapocalyptic nuances to really soak in, there's just one big gag at the center of the similarly end-times-minded "The Last Mall" -- how and why people might go shopping for things that a total Armageddon would render irrelevant -- and it's the difference between a song that works its way into your subconscious and a song that makes you say "I get it.”

A couple concepts sound cleverly modernized enough -- the team of deity-targeting assassins in the pulpy "Godwhacker" would make for a hell of a Vertigo comics series, and "Pixeleen" is a sly riff on post-cyberpunk blockbuster video game/film objectification. But casting a jaundiced eye towards the contemporary world's stumbles towards increasingly ludicrous forms of masculine cool is the kind of gig that requires a faster turnaround time than your average perfectionist can afford these days. But most of the record is filled with half-formed observations and obvious jabs that are nudge-your-ribs ironic -- check how blatantly post-split-up lament "Things I Miss the Most" veers towards the surrender of luxury goods ("The Audi TT/The house on the Vineyard") as a loss on par with companionship, or how "Slang Of Ages" hammers in how pathetic some poorly juxtaposed, once-cool dialect sounds in the wrong (aging) hands.

But it's the arrangement that really lets the vibe down. It's easily the least-catchy Steely Dan album ever recorded -- never forget that back in the '70s there were always deathless hooks and striking melodies there to justify all that highly touted musicianship, where here there's nothing but ambience. And it's a sanitized, antiseptic ambience, too. The sleekness sounds Teflon-slick, the moments meant to be calmly louche feel totally spent, and their once agile sense of creating a fluid sense of rhythm, whether mellow or ramped-up, somehow winds up sounding too stiff to swing. Which is a shame, since Becker and Fagen contributed more to the actual instrumental recordings than at any point since their early days -- Becker even contributes his first-ever lead vocal on "Slang Of Ages" (and sounds jarringly out of place). Everything just went.

The comeback that sprung from Two Against Nature seems like a blip on the radar compared to the critical reevaluation and generational carryover that the first wave of Steely Dan's records received in its wake. And maybe you could chalk that up to said comeback resulting in all of two studio albums, the most recent one nearly a dozen years old; there are two pretty good Donald Fagen solo records in far more recent memory. As a side effect, Everything Must Go feels like an official final statement, cutting off the notion of Steely Dan as a continuing enterprise and cementing them as something more of a legacy act, a name for Becker and Fagen to operate under in the past tense while they do their own things with separate autonomy. It doesn't hurt the case that the title cut's the closing track, and bears all the signs of a metaphor for the end of a once-successful enterprise liquidating its assets.

It's an obvious, to-the-point analogy -- and that's part of the problem. Allusions that made personal specificity out of familiar themes always stood as one of the best strengths of Steely Dan's songwriting, and Everything Must Go makes the themes far more obvious than they had been at any point in the band's discography. Where it took a few listens to a song like Countdown To Ecstasy's "King Of The World" for the postapocalyptic nuances to really soak in, there's just one big gag at the center of the similarly end-times-minded "The Last Mall" -- how and why people might go shopping for things that a total Armageddon would render irrelevant -- and it's the difference between a song that works its way into your subconscious and a song that makes you say "I get it.”

A couple concepts sound cleverly modernized enough -- the team of deity-targeting assassins in the pulpy "Godwhacker" would make for a hell of a Vertigo comics series, and "Pixeleen" is a sly riff on post-cyberpunk blockbuster video game/film objectification. But casting a jaundiced eye towards the contemporary world's stumbles towards increasingly ludicrous forms of masculine cool is the kind of gig that requires a faster turnaround time than your average perfectionist can afford these days. But most of the record is filled with half-formed observations and obvious jabs that are nudge-your-ribs ironic -- check how blatantly post-split-up lament "Things I Miss the Most" veers towards the surrender of luxury goods ("The Audi TT/The house on the Vineyard") as a loss on par with companionship, or how "Slang Of Ages" hammers in how pathetic some poorly juxtaposed, once-cool dialect sounds in the wrong (aging) hands.

But it's the arrangement that really lets the vibe down. It's easily the least-catchy Steely Dan album ever recorded -- never forget that back in the '70s there were always deathless hooks and striking melodies there to justify all that highly touted musicianship, where here there's nothing but ambience. And it's a sanitized, antiseptic ambience, too. The sleekness sounds Teflon-slick, the moments meant to be calmly louche feel totally spent, and their once agile sense of creating a fluid sense of rhythm, whether mellow or ramped-up, somehow winds up sounding too stiff to swing. Which is a shame, since Becker and Fagen contributed more to the actual instrumental recordings than at any point since their early days -- Becker even contributes his first-ever lead vocal on "Slang Of Ages" (and sounds jarringly out of place). Everything just went.

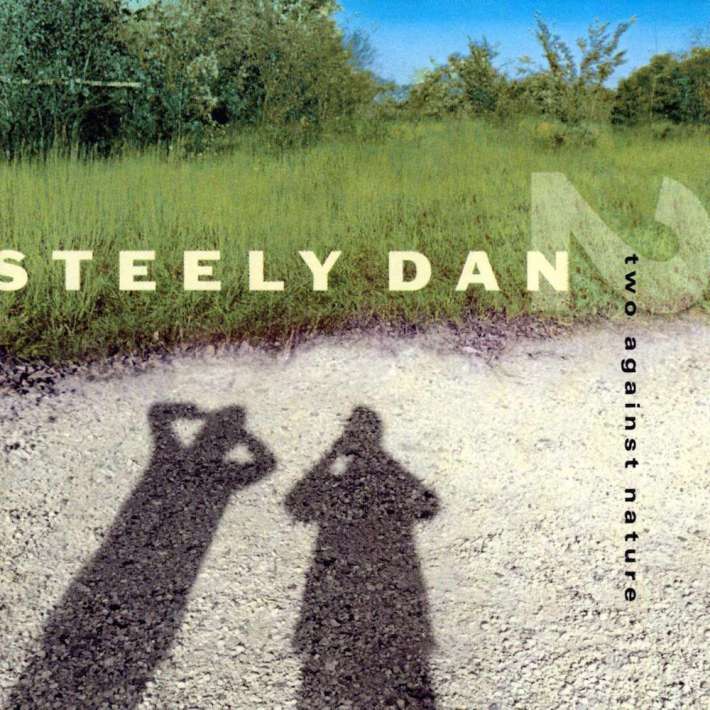

With post-Dan solo releases being sporadic throughout the '80s and '90s -- represented solely by Fagen's The Nightfly (1982) and Kamakiriad (1993) and Becker's 11 Tracks Of Whack (1994) -- their legacy spent two decades slowly being slotted into a classic rock canon they were often at strange odds with. (Ever hear "Reelin' in the Years" or "Josie" sandwiched between Foreigner and Bob Seger? It's like a transmission from another planet.) So after spending much of the '90s touring and reestablishing their history with releases like the box set Citizen Steely Dan, the prospect of a new album was a potentially pretty big deal. In retrospect, though, it only got partway "there" in the popular consciousness. It received decent reviews -- decent enough, anyways -- and hit a not-disastrous #6 on Billboard's album charts. But in a year where they were pitted against Gen-X favorites like Beck, Eminem, and Radiohead for Album of the Year Grammy, their win for Two Against Nature still gets held up as one of the most surprising (or, less charitably, "maddening") wins of all time. Between the skeptical aging fans who felt it didn't measure up to Aja and the youth-movement poptimists who scarcely cared about a band that last hit the charts when future record-buyers were still in preschool, there were a lot of reasons people turned their noses up at this one.

And yet there's still something to it: Two Against Nature is a case of an album being delivered by the people who you would most trust to put it out, just at a time when their reintroduction to the mainstream pop world felt strangely out of step. The music industry was still reeling from the artificial high of the pre-filesharing late '90s, where the tastes of teenagers were dominating the charts more than any time since the peak-Boomer '60s. So into this fray of Slim Shady dick jokes and Britney Spears provocation come a couple fiftysomething jazz weirdos with an album dominated by songs about sexual derangement. In "Gaslighting Abbie," a man and the woman he's cheating with plot to drive the man's wife insane; "Negative Girl" and "Almost Gothic" are love songs to women whose mood swings and personality crises make them inexplicably appealing; "Cousin Dupree" is lite-incest desperation (and, go figure, the big single). The allusions aren't quite as sly as they used to be, but the bite hits the bone -- when the breeziest, cheeriest thing on the record is "Janie Runaway," an idealized ode to seducing a missing teenager with the kind of pitch you could imagine Taxi Driver's Keitel-pimp Sport giving Jodie Foster's Iris, it's clear you're still dealing with some dark comedy venom here.

So maybe the relatively flat production is what helps it pass muster this time around, as opposed to having light ideas left fluttering through the impactless, vague odor that permeates Everything Must Go. The smoother, the creepier, maybe -- ironic counterpoints filtered through shiny state-of-the-art Audio Product Refinement, easy listening for uneasy realizations. That doesn't make the funk-lite fussiness that much more memorable, granted, and for every lead vocal where Fagen makes being broken in the brain sound like the apotheosis of class and refinement over electric pianos you could swim through, there's this odd sense that all the edges have been filed down just a little too much, like the drums have been run through an autoclave to get rid of any unseemly residue of intensity or drive. Still, it's fun to think of how many well-intentioned wine-tasting party soundtracks have been turned weird by this record -- if not by the deranged plotting of opener "Gaslighting Abbie," then definitely by "What A Shame About Me," a strong entry in the great canon of works about Failing in New York: "I said babe you look delicious/And you're standing very close/But like this is Lower Broadway/And you're talking to a ghost.”

With post-Dan solo releases being sporadic throughout the '80s and '90s -- represented solely by Fagen's The Nightfly (1982) and Kamakiriad (1993) and Becker's 11 Tracks Of Whack (1994) -- their legacy spent two decades slowly being slotted into a classic rock canon they were often at strange odds with. (Ever hear "Reelin' in the Years" or "Josie" sandwiched between Foreigner and Bob Seger? It's like a transmission from another planet.) So after spending much of the '90s touring and reestablishing their history with releases like the box set Citizen Steely Dan, the prospect of a new album was a potentially pretty big deal. In retrospect, though, it only got partway "there" in the popular consciousness. It received decent reviews -- decent enough, anyways -- and hit a not-disastrous #6 on Billboard's album charts. But in a year where they were pitted against Gen-X favorites like Beck, Eminem, and Radiohead for Album of the Year Grammy, their win for Two Against Nature still gets held up as one of the most surprising (or, less charitably, "maddening") wins of all time. Between the skeptical aging fans who felt it didn't measure up to Aja and the youth-movement poptimists who scarcely cared about a band that last hit the charts when future record-buyers were still in preschool, there were a lot of reasons people turned their noses up at this one.

And yet there's still something to it: Two Against Nature is a case of an album being delivered by the people who you would most trust to put it out, just at a time when their reintroduction to the mainstream pop world felt strangely out of step. The music industry was still reeling from the artificial high of the pre-filesharing late '90s, where the tastes of teenagers were dominating the charts more than any time since the peak-Boomer '60s. So into this fray of Slim Shady dick jokes and Britney Spears provocation come a couple fiftysomething jazz weirdos with an album dominated by songs about sexual derangement. In "Gaslighting Abbie," a man and the woman he's cheating with plot to drive the man's wife insane; "Negative Girl" and "Almost Gothic" are love songs to women whose mood swings and personality crises make them inexplicably appealing; "Cousin Dupree" is lite-incest desperation (and, go figure, the big single). The allusions aren't quite as sly as they used to be, but the bite hits the bone -- when the breeziest, cheeriest thing on the record is "Janie Runaway," an idealized ode to seducing a missing teenager with the kind of pitch you could imagine Taxi Driver's Keitel-pimp Sport giving Jodie Foster's Iris, it's clear you're still dealing with some dark comedy venom here.

So maybe the relatively flat production is what helps it pass muster this time around, as opposed to having light ideas left fluttering through the impactless, vague odor that permeates Everything Must Go. The smoother, the creepier, maybe -- ironic counterpoints filtered through shiny state-of-the-art Audio Product Refinement, easy listening for uneasy realizations. That doesn't make the funk-lite fussiness that much more memorable, granted, and for every lead vocal where Fagen makes being broken in the brain sound like the apotheosis of class and refinement over electric pianos you could swim through, there's this odd sense that all the edges have been filed down just a little too much, like the drums have been run through an autoclave to get rid of any unseemly residue of intensity or drive. Still, it's fun to think of how many well-intentioned wine-tasting party soundtracks have been turned weird by this record -- if not by the deranged plotting of opener "Gaslighting Abbie," then definitely by "What A Shame About Me," a strong entry in the great canon of works about Failing in New York: "I said babe you look delicious/And you're standing very close/But like this is Lower Broadway/And you're talking to a ghost.”

Steely Dan's second album starts with a giddy flourish of pure hyper-swing mania and ends with post-apocalyptic ruin. If that sounds like a wide gamut to run, Countdown To Ecstasy sprawls all the way out; in the interim you also get woozy balladry and stage-band stomping, Cajun-adjacent twang-soul and icy samba on vibes, fusion-style complexity and deep, deep hooks. It's a big flailing identity-scrambling polyglot, a band already hot out the gates very quickly deciding that it's time to branch out. It would almost be some kind of bewildering disaster except for the fact that they hit nearly every single distantly spaced target dead center. Can the same band pull off both a boogie-frenzied chops-expo ("Bodhisattva") and a weepy country love song ("Pearl Of The Quarter")? Well, if you feel like sticking around to find out, you'll also get the opportunity to hear "My Old School," which is a real killer even if you don't give a damn about old Bard College pot bust stories. (Chevy Chase played drums with 'em back then, y'know.)

It should be noted that this is the only Steely Dan album actually composed with specific band members in mind, arrangements fine-tuned to each player's working methods and abilities. The abilities in question are pretty much limitless, at least if "Bodhisattva" is enough to clue you in; not for nothing does that song kick off the whole deal and push forward the whole notion that these guys aren't just a bunch of slick word-slingers. Of course, the words slung are worthy of noting -- "Bodhisattva" as a tongue-in-cheek eyeroll towards Western Orientalism (dig the intentionally vague, inane conflation "The shine of your Japan/The sparkle of your China"), the money-where-your-mouth-is jousting of "Your Gold Teeth," "King Of The World" and its lonely broadcasting into the void, and "Show Biz Kids" as a bewildered careen through the machinations of the New York-reared writers' adopted West Coast home turf (liner annotations: "The Dan moves to L.A. and is forced to give an oral report"). This is how good they sounded when they were scattershot -- enjoy it while knowing that there's cohesion yet to come.

Steely Dan's second album starts with a giddy flourish of pure hyper-swing mania and ends with post-apocalyptic ruin. If that sounds like a wide gamut to run, Countdown To Ecstasy sprawls all the way out; in the interim you also get woozy balladry and stage-band stomping, Cajun-adjacent twang-soul and icy samba on vibes, fusion-style complexity and deep, deep hooks. It's a big flailing identity-scrambling polyglot, a band already hot out the gates very quickly deciding that it's time to branch out. It would almost be some kind of bewildering disaster except for the fact that they hit nearly every single distantly spaced target dead center. Can the same band pull off both a boogie-frenzied chops-expo ("Bodhisattva") and a weepy country love song ("Pearl Of The Quarter")? Well, if you feel like sticking around to find out, you'll also get the opportunity to hear "My Old School," which is a real killer even if you don't give a damn about old Bard College pot bust stories. (Chevy Chase played drums with 'em back then, y'know.)

It should be noted that this is the only Steely Dan album actually composed with specific band members in mind, arrangements fine-tuned to each player's working methods and abilities. The abilities in question are pretty much limitless, at least if "Bodhisattva" is enough to clue you in; not for nothing does that song kick off the whole deal and push forward the whole notion that these guys aren't just a bunch of slick word-slingers. Of course, the words slung are worthy of noting -- "Bodhisattva" as a tongue-in-cheek eyeroll towards Western Orientalism (dig the intentionally vague, inane conflation "The shine of your Japan/The sparkle of your China"), the money-where-your-mouth-is jousting of "Your Gold Teeth," "King Of The World" and its lonely broadcasting into the void, and "Show Biz Kids" as a bewildered careen through the machinations of the New York-reared writers' adopted West Coast home turf (liner annotations: "The Dan moves to L.A. and is forced to give an oral report"). This is how good they sounded when they were scattershot -- enjoy it while knowing that there's cohesion yet to come.

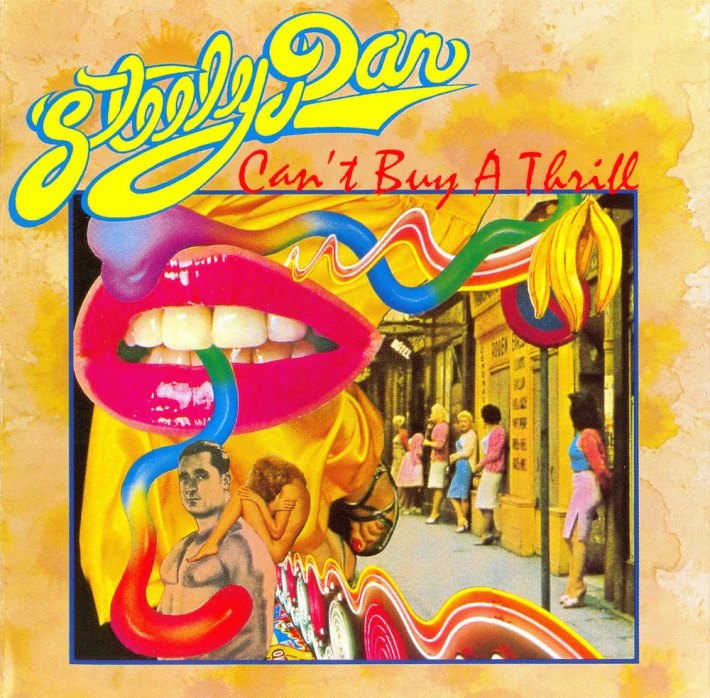

First there was a so-what single -- 1972's "Dallas" b/w "Sail The Waterway," both denied Greatest Hits throw-in status and Citizen Steely Dan box set enshrinement -- and then, very shortly afterwards, there was The Arrival. It's not out of the question to call Can't Buy A Thrill one of the decade's best debut albums, even in an era where LPs were not only expected to trump singles but be exhaustively comprehensive portfolios in themselves. But the three songs that made the top tier of their repertoire -- "Do It Again," "Dirty Work," and "Reelin' in the Years" -- are bolstered by a bunch of deep cuts that run the gamut from good (the anti-escapist mutant bossa "Only A Fool Would Say That") to staggering (lost souls anthem "Midnite Cruiser"). For a record that holds the weight of so many formative components later lost -- chief amongst them the presence of lead vocalist David Palmer, whose delicately pained warmth on "Dirty Work" is one of the band's most human moments -- everything that comes after Can't Buy A Thrill still feels rooted somewhere in its counterculture-hangover vibe.

And while the record's distinct themes of weariness, monomania, and displacement haven't been widely attributed to the Death of the Sixties, it sure reads like it. "Dirty Work" is the upper-middle-class take on free love -- which goes hand-in-hand with surreptitious infidelity and unshakeable guilt ("I foresee terrible trouble/And I stay here just the same"). "Kings" is given the deadpan annotation "No political significance" on the back of the sleeve, but whether or not Good King Richard is Nixon and Good King John is Kennedy, there's no blaming anyone who hears a heartfelt, timely protest in the line "While he plundered far and wide/All his starving children cried/And though we sung his fame/We all went hungry just the same.” ('72 was a memorably feverish election year, after all.) "Do It Again," rendered dizzying and alien and archly beautiful thanks to electric sitar (Denny Dias) and cheapie plastic combo organ (Fagen), is Kipling's "If" turned into Sisyphus clusterfuck, an ellipsis at the end of a sentence about the futility of trying to force change no matter how busted you wind up without it. That, not the innocuous travelin'-man ballad "Dallas,"was their breakthrough single, a bizarro jazz-funk crossover/near-instant standard (see: fusioneer Deodato; Philly soulster Charles Mann; micropress funk obscurities Deep Heat); imagine the context where an ode to recidivism grabs the pulse of a nation and there's your first step to making Steely Dan famous.

Plus, holy damn, can we take a moment to give it up for "Reelin' in the Years"? If you want to hold up the Dan as top-tier songwriters, there is no beating "You been tellin' me you're a genius since you were seventeen/In all the time I've known you I still don't know what you mean" for the way it scans, the up-front simplicity, and how brutally, hilariously cold it is. And the old "Don and Walt and some friends in the studio" perception of the band's makeup doesn't quite do justice to the fact that the hired hands they brought on were capable of astounding feats both technical and emotional; Elliott Randall's guitar solos (rumored to be Jimmy Page's all-time favorite) use virtuoso wailing in the service of jabbing, wiseassed, gleefully sharp-witted antagonism -- strings played like a saxophone. And, unlike the later years' borderline-Kubrickian multi-take perfectionism, it took him just two run-throughs to get it down perfect; the only reason it required that many is because the assistant engineer forgot to hit "record" on the first one. Sometimes things just clicked for them -- best of all when they were still figuring out how to click in the first place.

First there was a so-what single -- 1972's "Dallas" b/w "Sail The Waterway," both denied Greatest Hits throw-in status and Citizen Steely Dan box set enshrinement -- and then, very shortly afterwards, there was The Arrival. It's not out of the question to call Can't Buy A Thrill one of the decade's best debut albums, even in an era where LPs were not only expected to trump singles but be exhaustively comprehensive portfolios in themselves. But the three songs that made the top tier of their repertoire -- "Do It Again," "Dirty Work," and "Reelin' in the Years" -- are bolstered by a bunch of deep cuts that run the gamut from good (the anti-escapist mutant bossa "Only A Fool Would Say That") to staggering (lost souls anthem "Midnite Cruiser"). For a record that holds the weight of so many formative components later lost -- chief amongst them the presence of lead vocalist David Palmer, whose delicately pained warmth on "Dirty Work" is one of the band's most human moments -- everything that comes after Can't Buy A Thrill still feels rooted somewhere in its counterculture-hangover vibe.

And while the record's distinct themes of weariness, monomania, and displacement haven't been widely attributed to the Death of the Sixties, it sure reads like it. "Dirty Work" is the upper-middle-class take on free love -- which goes hand-in-hand with surreptitious infidelity and unshakeable guilt ("I foresee terrible trouble/And I stay here just the same"). "Kings" is given the deadpan annotation "No political significance" on the back of the sleeve, but whether or not Good King Richard is Nixon and Good King John is Kennedy, there's no blaming anyone who hears a heartfelt, timely protest in the line "While he plundered far and wide/All his starving children cried/And though we sung his fame/We all went hungry just the same.” ('72 was a memorably feverish election year, after all.) "Do It Again," rendered dizzying and alien and archly beautiful thanks to electric sitar (Denny Dias) and cheapie plastic combo organ (Fagen), is Kipling's "If" turned into Sisyphus clusterfuck, an ellipsis at the end of a sentence about the futility of trying to force change no matter how busted you wind up without it. That, not the innocuous travelin'-man ballad "Dallas,"was their breakthrough single, a bizarro jazz-funk crossover/near-instant standard (see: fusioneer Deodato; Philly soulster Charles Mann; micropress funk obscurities Deep Heat); imagine the context where an ode to recidivism grabs the pulse of a nation and there's your first step to making Steely Dan famous.

Plus, holy damn, can we take a moment to give it up for "Reelin' in the Years"? If you want to hold up the Dan as top-tier songwriters, there is no beating "You been tellin' me you're a genius since you were seventeen/In all the time I've known you I still don't know what you mean" for the way it scans, the up-front simplicity, and how brutally, hilariously cold it is. And the old "Don and Walt and some friends in the studio" perception of the band's makeup doesn't quite do justice to the fact that the hired hands they brought on were capable of astounding feats both technical and emotional; Elliott Randall's guitar solos (rumored to be Jimmy Page's all-time favorite) use virtuoso wailing in the service of jabbing, wiseassed, gleefully sharp-witted antagonism -- strings played like a saxophone. And, unlike the later years' borderline-Kubrickian multi-take perfectionism, it took him just two run-throughs to get it down perfect; the only reason it required that many is because the assistant engineer forgot to hit "record" on the first one. Sometimes things just clicked for them -- best of all when they were still figuring out how to click in the first place.

If you want a good waypoint for where Steely Dan truly earned their rep for delivering acidic fatalism under cover of unflappable smoothness, here's where their ennui finally curdled. When MCA reissued Katy Lied in remastered form in 1999, Becker and Fagen used their collective liner-notes voice to try and clear up whatever mindstate it was that they'd clambered into in the wake of a tumultuous, Valium-addled 1974. They'd grown weary of touring life and all the hassles it brought (per said liner notes: "we had long since come to the conclusion that certain individuals were not suited by temperament or constitution to the rigors of long road trips in the company of superannuated prep school hooligans"), while the rest of the band became increasingly agitated about the prospect of being sequestered in the studio for three dozen takes. Once-integral members -- guitarist Jeff "Skunk" Baxter and drummer Jim Hodder chief amongst them -- peeled away from the core group and were replaced with a rotation of session players. As a touring concern, Steely Dan were done, the biggest scrap of evidence relegated to the 1980 "Hey Nineteen" single's b-side: a performance of "Bodhisattva" from their final show on July 4, 1974 at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, preceded by two and a half minutes of the world's drunkest Teamster giving them a rambling introduction. This was considered a hazardous working environment.

And so, without a band or a manager or a reasonable amount of money or much of anything else, Becker and Fagen holed up in the offices of ABC's imminently doomed Dunhill Records imprint to write the songs that would eventually become Katy Lied. And a lot of them seethed like never before. The ways in which they seethed were rangy, often drenched in wit and charisma and disguised as paeans to self-reinvention and/or self-negation: the speculator in "Black Friday" who sees the next big imminent calamity as a good excuse to fuck around on some lost-weekend tomfoolery; the farewell to the presence of a career dirtbag booze-and-guns aficionado in "Daddy Don't Live In That New York City No More"; the roamer of "Any World (That I'm Welcome To)" who, amidst his optimistic daydreaming, lets slip the despair of "the one I come from.” But now-what ambivalence isn't exactly a grand step up from cynicism, and the seediness is hard to shake, with the predatory con-job m.o.s of teen-luring skin-flick screeners ("Everyone's Gone to The Movies") and outsiders playing undercover for cryptic rewards -- drugs? women? live gigs? ("Throw Back The Little Ones") -- all calling the shots. As for fan-favorite "Doctor Wu," an existential gem about friendship in the face of relationship woes, Fagen eventually revealed that the song was really about a love triangle -- between a woman, a man, and heroin.

But all that sordid business was offset by the first dedicated version of their studio-juggernaut ensemble, the five-man instrumental core of Becker-Fagen-Baxter-Dias-Hodder now pared down to Walter, Donald, Denny, and a whole gang of their favorite sidemen. They found the idea of having modular cohorts they could swap in and out more liberating than the usual set-in-stone dynamic beloved by the kinds of rock groups that actually put photos of themselves on the album cover. And yet their auteurism meant that even with different guitarists soloing on nearly every track and a twenty-year-old kid from the Sonny and Cher band on the drums (spoiler: that kid was future go-to super-sessionman Jeff Porcaro), it all held together and streamlined their rock, jazz, and R&B facets into a cohesive, immediate identity. It didn't hurt that Fagen, once unsatisfied with his voice, had really begun to work out and play to its strengths -- the sinister leer, the plaintive shakiness, the moments of out-of-nowhere intricacy -- that slunk around his words like a displaced jazzbo Dylan. And if he couldn't (or didn't want to) pull off the high notes, at least they corralled this guy named Michael McDonald to help out.

Bad luck struck, however, and Katy Lied is a 13th floor superstitiously relabeled as the 14th, so to speak. There was a technological disaster alluded to on the sleeve via some hyperbolic faux-audiophile hi-fi gobbledegook that excused the sound as the end result of impossible-to-meet standards. ("Transfer from master tapes to master lacquers is done on a Neumann VMS 70 computerized lathe equipped with a variable pitch, variable depth helium cooled cutting head.") That slice of bitter humor pertains to the fact that the fancy-assed new dbx-branded noise reduction system the studio used straight-up wrecked the album's sound quality somewhere in the mixing process, with just enough salvaged after the fact to make the record sound marginally acceptable. Becker and Fagen still refused to listen to the final product out of sheer mortification, but even if the fidelity never got tweaked back to what they'd originally envisioned, the increasingly immaculate everything-just-so quality of the arrangements still shines through.

If you want a good waypoint for where Steely Dan truly earned their rep for delivering acidic fatalism under cover of unflappable smoothness, here's where their ennui finally curdled. When MCA reissued Katy Lied in remastered form in 1999, Becker and Fagen used their collective liner-notes voice to try and clear up whatever mindstate it was that they'd clambered into in the wake of a tumultuous, Valium-addled 1974. They'd grown weary of touring life and all the hassles it brought (per said liner notes: "we had long since come to the conclusion that certain individuals were not suited by temperament or constitution to the rigors of long road trips in the company of superannuated prep school hooligans"), while the rest of the band became increasingly agitated about the prospect of being sequestered in the studio for three dozen takes. Once-integral members -- guitarist Jeff "Skunk" Baxter and drummer Jim Hodder chief amongst them -- peeled away from the core group and were replaced with a rotation of session players. As a touring concern, Steely Dan were done, the biggest scrap of evidence relegated to the 1980 "Hey Nineteen" single's b-side: a performance of "Bodhisattva" from their final show on July 4, 1974 at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, preceded by two and a half minutes of the world's drunkest Teamster giving them a rambling introduction. This was considered a hazardous working environment.

And so, without a band or a manager or a reasonable amount of money or much of anything else, Becker and Fagen holed up in the offices of ABC's imminently doomed Dunhill Records imprint to write the songs that would eventually become Katy Lied. And a lot of them seethed like never before. The ways in which they seethed were rangy, often drenched in wit and charisma and disguised as paeans to self-reinvention and/or self-negation: the speculator in "Black Friday" who sees the next big imminent calamity as a good excuse to fuck around on some lost-weekend tomfoolery; the farewell to the presence of a career dirtbag booze-and-guns aficionado in "Daddy Don't Live In That New York City No More"; the roamer of "Any World (That I'm Welcome To)" who, amidst his optimistic daydreaming, lets slip the despair of "the one I come from.” But now-what ambivalence isn't exactly a grand step up from cynicism, and the seediness is hard to shake, with the predatory con-job m.o.s of teen-luring skin-flick screeners ("Everyone's Gone to The Movies") and outsiders playing undercover for cryptic rewards -- drugs? women? live gigs? ("Throw Back The Little Ones") -- all calling the shots. As for fan-favorite "Doctor Wu," an existential gem about friendship in the face of relationship woes, Fagen eventually revealed that the song was really about a love triangle -- between a woman, a man, and heroin.

But all that sordid business was offset by the first dedicated version of their studio-juggernaut ensemble, the five-man instrumental core of Becker-Fagen-Baxter-Dias-Hodder now pared down to Walter, Donald, Denny, and a whole gang of their favorite sidemen. They found the idea of having modular cohorts they could swap in and out more liberating than the usual set-in-stone dynamic beloved by the kinds of rock groups that actually put photos of themselves on the album cover. And yet their auteurism meant that even with different guitarists soloing on nearly every track and a twenty-year-old kid from the Sonny and Cher band on the drums (spoiler: that kid was future go-to super-sessionman Jeff Porcaro), it all held together and streamlined their rock, jazz, and R&B facets into a cohesive, immediate identity. It didn't hurt that Fagen, once unsatisfied with his voice, had really begun to work out and play to its strengths -- the sinister leer, the plaintive shakiness, the moments of out-of-nowhere intricacy -- that slunk around his words like a displaced jazzbo Dylan. And if he couldn't (or didn't want to) pull off the high notes, at least they corralled this guy named Michael McDonald to help out.

Bad luck struck, however, and Katy Lied is a 13th floor superstitiously relabeled as the 14th, so to speak. There was a technological disaster alluded to on the sleeve via some hyperbolic faux-audiophile hi-fi gobbledegook that excused the sound as the end result of impossible-to-meet standards. ("Transfer from master tapes to master lacquers is done on a Neumann VMS 70 computerized lathe equipped with a variable pitch, variable depth helium cooled cutting head.") That slice of bitter humor pertains to the fact that the fancy-assed new dbx-branded noise reduction system the studio used straight-up wrecked the album's sound quality somewhere in the mixing process, with just enough salvaged after the fact to make the record sound marginally acceptable. Becker and Fagen still refused to listen to the final product out of sheer mortification, but even if the fidelity never got tweaked back to what they'd originally envisioned, the increasingly immaculate everything-just-so quality of the arrangements still shines through.

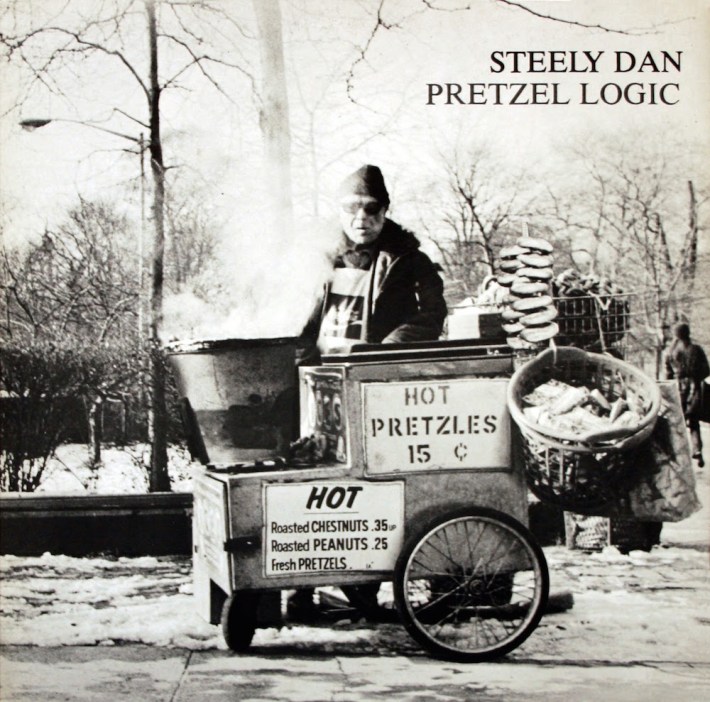

A stylistic regrouping after the mad sprawl of Countdown To Ecstasy, Pretzel Logic boasts the paradox of having more songs (eleven) and a shorter runtime (33 minutes and change) than any other Steely Dan record while still being one of their deepest, most immersive listens. Give credit to the second-best starting three of their whole catalog: the Horace Silver-interpolating harmonic lushness of "Rikki Don't Lose That Number," the shifty, itchy clavinet-hiccup desperado funk of "Night By Night," and the electric piano glow of Laurel Canyon comedown "Any Major Dude Will Tell You" (the best song Joni Mitchell never wrote) are the three songs that, in album-opening sequence, are accessible and sincere enough to win over most skeptics.

Those tracks provide momentum enough to carry the record through the remainder of what's still a pretty brisk Side A: "Barrytown" is a major standard in a better version of 1974, and their burbling upending of Bubber Miley and Duke Ellington's "East St. Louis Toodle-Oo" adds of-its-era wah-wah but doesn't subtract too much. Flip it over, and the situation gets frantic, short-yet-lively opuses in miniature that rattle through manic Bird homages ("Parker's Band") and string-coated ELO-isms ("Through With Buzz") and a gonzo diversion into outlaw country ("With A Gun"). But it doesn't scatter itself too far afield, and this is the record where their eclecticism starts to feel like the work of a discrete unit instead of a collection of parts.

It's also the record where they finally become both truly entrenched in the L.A. scene and uniquely at odds with it -- the album cover is black-and-white NYC in winter, about as far away as you can get from Santa Monica and still have a connection to the American music-biz machine. And as a striking side effect, Pretzel Logic feels like their most wistful, isolated record -- everyone's lonely here, even Napoleon. When the humid blues of the title track keeps culminating in the realization that nostalgic wishful thinking for a time and place to fit in is asking for the impossible -- "those days are gone forever/over a long time ago" -- it stings hard, just like the pleas for Rikki's change of heart or the rejection of that schlemiel from Barrytown. Even "Any Major Dude," the Dan's finest moment of outreach and empathy for one of the countless woeful souls that populate their songs, has a bridge that hinges on stark reality worthy of Teddy Pendergrass three years on: "you can try to run but you can't hide from what's inside of you." That Becker and Fagen were starting to bring in the best session players they could find to help them realize the full sonic potential of this loneliness is an irony that's not only not lost, but is more or less integral to the whole crazy enterprise.

A stylistic regrouping after the mad sprawl of Countdown To Ecstasy, Pretzel Logic boasts the paradox of having more songs (eleven) and a shorter runtime (33 minutes and change) than any other Steely Dan record while still being one of their deepest, most immersive listens. Give credit to the second-best starting three of their whole catalog: the Horace Silver-interpolating harmonic lushness of "Rikki Don't Lose That Number," the shifty, itchy clavinet-hiccup desperado funk of "Night By Night," and the electric piano glow of Laurel Canyon comedown "Any Major Dude Will Tell You" (the best song Joni Mitchell never wrote) are the three songs that, in album-opening sequence, are accessible and sincere enough to win over most skeptics.

Those tracks provide momentum enough to carry the record through the remainder of what's still a pretty brisk Side A: "Barrytown" is a major standard in a better version of 1974, and their burbling upending of Bubber Miley and Duke Ellington's "East St. Louis Toodle-Oo" adds of-its-era wah-wah but doesn't subtract too much. Flip it over, and the situation gets frantic, short-yet-lively opuses in miniature that rattle through manic Bird homages ("Parker's Band") and string-coated ELO-isms ("Through With Buzz") and a gonzo diversion into outlaw country ("With A Gun"). But it doesn't scatter itself too far afield, and this is the record where their eclecticism starts to feel like the work of a discrete unit instead of a collection of parts.

It's also the record where they finally become both truly entrenched in the L.A. scene and uniquely at odds with it -- the album cover is black-and-white NYC in winter, about as far away as you can get from Santa Monica and still have a connection to the American music-biz machine. And as a striking side effect, Pretzel Logic feels like their most wistful, isolated record -- everyone's lonely here, even Napoleon. When the humid blues of the title track keeps culminating in the realization that nostalgic wishful thinking for a time and place to fit in is asking for the impossible -- "those days are gone forever/over a long time ago" -- it stings hard, just like the pleas for Rikki's change of heart or the rejection of that schlemiel from Barrytown. Even "Any Major Dude," the Dan's finest moment of outreach and empathy for one of the countless woeful souls that populate their songs, has a bridge that hinges on stark reality worthy of Teddy Pendergrass three years on: "you can try to run but you can't hide from what's inside of you." That Becker and Fagen were starting to bring in the best session players they could find to help them realize the full sonic potential of this loneliness is an irony that's not only not lost, but is more or less integral to the whole crazy enterprise.

As the '70s drew to a close, it looked like Steely Dan were in a breakneck race with Fleetwood Mac to see whose followup to a massive '77 blockbuster would wind up more star-crossed. While the Mac finally got their million-dollar new wave-ish double LP opus Tusk out to a somewhat less receptive public before the decade rolled over, Gaucho was born out of a cavalcade of misfortunes that ground Steely Dan's album-a-year proficiency into debris and saw them limp defeated into the soon-inhospitable '80s. To many people, including the band members themselves, Gaucho is a what-could've-been story: so many lost opportunities, rumored and hinted at but only surfacing decades later on muddy bootlegs, the final product on record store shelves more of a salvage job than an original vision. Massively overbudget, wracked with technical nightmares and health-jeopardizing accidents, held up in label-rights limbo, and delayed far beyond the point of belief, its labor pains were eerily reminiscent of the last throes of New Hollywood's auteurist freedom before focus-grouped blockbusters took the reins again.

That said, Apocalypse Now is a hell of a film, ain't it? Gaucho is in that same ballpark, success-wise and (mostly) critically, a work of art that only sounds like it took forever in terms of meticulousness. Even after losing a pivotal song, "The Second Arrangement," to an assistant engineer's tape-erasing screwup, even after subsequently scrapping, possibly out of sheer spite, a handful of additional songs that could've been certified Aja-mode classics ("The Bear" and its Isleys-gone-beatnik eeriness is a stunner), even after Walter Becker endured both the overdose death of his girlfriend and injuries from getting hit by a car that left him on crutches, even after MCA used their upper hand in the contract dispute as an excuse to bump the LP's price to a dollar higher than the rest of the label's catalog… even after all that, Gaucho wound up worth the turmoil, at least for listeners. It also tore Becker and Fagen apart as songwriting partners, but ending -- at least temporarily -- on a top 10 platinum record with at least a few fan-favorite songs is a strong way to go out.

And it does sound like the end of something, whether or not the whole ordeal shut the doors on the band as a going concern. Gaucho is the self-aware aging hipster's reckoning with the decline of Boomer cool; where Tusk flirted with New Wave, "Babylon Sisters" and "Hey Nineteen" and "My Rival" and "Glamour Profession" try to find rejuvenation in meaningless flings, in other peoples' youth ("Hey Nineteen"), in wounded, shamed revenge ("My Rival"), in the cool-by-association of being a dealer to the stars ("Glamour Profession"). So from the words on down, everything on this record throbs with cumulative uncertainty: will the session players flown in to Manhattan from L.A. be the same 40-take workhorses, or will their coke-naut adventures knock them out of joint? Should the Dan just give in to using a tricked-out, super-sophisticated drum machine for the humanly impossible fills, offering it a real-live-boy name ("Wendel") so MCA can whimsically award it its own platinum plaque? How long will it take to get that "Babylon Sisters" fadeout just right in the mix? There are only seven corners of this faded, damaged corner of modern-man panic to visit here, but whether it's rictus-grinningly upbeat (smudgelessly shiny demi-disco on "Glamour Profession") or a white-knuckled slow jam ("Third World Man" is like finding euphoria by drowning in a jacuzzi), the cumulative effect is devastating.

As the '70s drew to a close, it looked like Steely Dan were in a breakneck race with Fleetwood Mac to see whose followup to a massive '77 blockbuster would wind up more star-crossed. While the Mac finally got their million-dollar new wave-ish double LP opus Tusk out to a somewhat less receptive public before the decade rolled over, Gaucho was born out of a cavalcade of misfortunes that ground Steely Dan's album-a-year proficiency into debris and saw them limp defeated into the soon-inhospitable '80s. To many people, including the band members themselves, Gaucho is a what-could've-been story: so many lost opportunities, rumored and hinted at but only surfacing decades later on muddy bootlegs, the final product on record store shelves more of a salvage job than an original vision. Massively overbudget, wracked with technical nightmares and health-jeopardizing accidents, held up in label-rights limbo, and delayed far beyond the point of belief, its labor pains were eerily reminiscent of the last throes of New Hollywood's auteurist freedom before focus-grouped blockbusters took the reins again.

That said, Apocalypse Now is a hell of a film, ain't it? Gaucho is in that same ballpark, success-wise and (mostly) critically, a work of art that only sounds like it took forever in terms of meticulousness. Even after losing a pivotal song, "The Second Arrangement," to an assistant engineer's tape-erasing screwup, even after subsequently scrapping, possibly out of sheer spite, a handful of additional songs that could've been certified Aja-mode classics ("The Bear" and its Isleys-gone-beatnik eeriness is a stunner), even after Walter Becker endured both the overdose death of his girlfriend and injuries from getting hit by a car that left him on crutches, even after MCA used their upper hand in the contract dispute as an excuse to bump the LP's price to a dollar higher than the rest of the label's catalog… even after all that, Gaucho wound up worth the turmoil, at least for listeners. It also tore Becker and Fagen apart as songwriting partners, but ending -- at least temporarily -- on a top 10 platinum record with at least a few fan-favorite songs is a strong way to go out.

And it does sound like the end of something, whether or not the whole ordeal shut the doors on the band as a going concern. Gaucho is the self-aware aging hipster's reckoning with the decline of Boomer cool; where Tusk flirted with New Wave, "Babylon Sisters" and "Hey Nineteen" and "My Rival" and "Glamour Profession" try to find rejuvenation in meaningless flings, in other peoples' youth ("Hey Nineteen"), in wounded, shamed revenge ("My Rival"), in the cool-by-association of being a dealer to the stars ("Glamour Profession"). So from the words on down, everything on this record throbs with cumulative uncertainty: will the session players flown in to Manhattan from L.A. be the same 40-take workhorses, or will their coke-naut adventures knock them out of joint? Should the Dan just give in to using a tricked-out, super-sophisticated drum machine for the humanly impossible fills, offering it a real-live-boy name ("Wendel") so MCA can whimsically award it its own platinum plaque? How long will it take to get that "Babylon Sisters" fadeout just right in the mix? There are only seven corners of this faded, damaged corner of modern-man panic to visit here, but whether it's rictus-grinningly upbeat (smudgelessly shiny demi-disco on "Glamour Profession") or a white-knuckled slow jam ("Third World Man" is like finding euphoria by drowning in a jacuzzi), the cumulative effect is devastating.

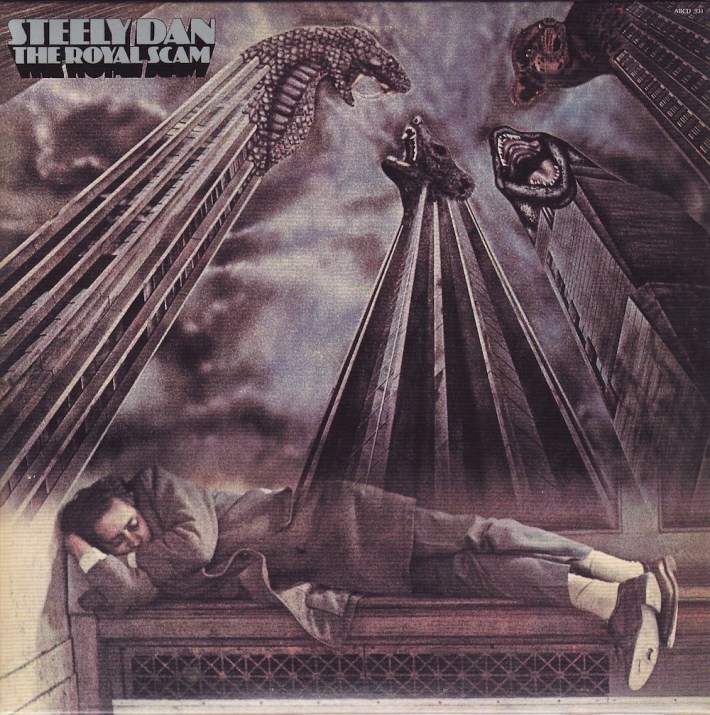

This is not a smooth record. It might fool you for a bit; there are some absolutely frictionless motions turning all the little gears in this piece of work. But as it turns out, nearly all these pop-song novellas are driven not by contentment but by escape -- from one bad situation to another one, assuming you even have so much as a destination. When the psychedelic trade bottoms out, when loneliness requires all your friends to be imaginary, when your go-to option as a fugitive is suicide by cop, when the unmeetable promises of Manhattan beckon you away from home... what are you going to do when the inevitable ripoff that pragmatists know well enough to avoid brazenly trips you up?

Aja gets the accolades, and deservingly so, but its immediate predecessor is everything great about Aja in its first full rush of inspiration -- the bicoastal feel, the inseparable merging of pop and chops -- run through with nearly wall-to-wall examples of their most to-the-bone storytelling songwriting. (Only "The Fez" and "Green Earrings" are lyrically abstract; they compensated by bumping enough that early '90s Ice Cube could rap over both of them.) Their fight-or-flight narratives lead shady fugitives to lawless space colonies on "Sign In Stranger," loner children to ponder the ancient history of art in "the Caves Of Altamira,” an unsatisfied wife to hook up with a hotel gigolo in "Haitian Divorce,” and Puerto Rican immigrants seeking a promised land only to get cordoned off in New York City ghettos and driven to addiction in the title cut. It's a bracing dose of world-weary cynicism, snuck in under the cover of cleverly arranged sophistication and (at least according to the guys with their names on the cover) some the most preposterous sleeve art of the decade.

At some points, it almost threatens to become too difficult to bear, but they save the unfiltered gut-punch vitriol for the very end in that titular closer, false promises of the American dream peeling away in the Copland-turned-sour arrangements. The other eight tracks leading up to it are dark, but darkly humorous, for the most part; when they're not, they're tempered with breathtaking musicianship. Opener and all-time classic "Kid Charlemagne" does both, regarding its Owsley-inspired psychotropics guru and his post-hippie-era downfall with equal parts admiration, envy, contempt, sympathy, and warning; it's endlessly quotable, loaded with double- and triple-entendre ("You are obsolete/Look at all the white men on the street" -- are they talking skin or bricks?), and delivered with an edge-of-panic precision in one of Fagen's sharpest lead vocals (twelve words: "Is there gas in the car/Yes there's gas in the caaaaar") and two vertigo-inducing moments of Larry Carlton's greatest guitar solos. Carlton's serrated heavy rock riffs also make the harrowing cornered-rat freakout of a holed-up criminal in "Don't Take Me Alive" into something weirdly stirring, and when the backup singers come in just before the second chorus -- right under the line "Here in this darkness/I know what I've done/I know all at once who I am" -- it's enough to snatch your breath. And when the vengeance-minded cuckold of "Everything You Did" tries to head off incrimination by telling his significant other to "turn up the Eagles, the neighbors are listening" (a story you might know one way or another), it turns a heated confrontation into a farce -- one that starts with threats and ends on a queasy fascination with just how the cheating played out.

All these densely evocative portraits of America in its post-Nixon hangover -- where the counterculture is spent, creatives have lost themselves, and fantasies have lashed back like bounced checks -- fully established Steely Dan in the mode they're best known for. And even if it's still a divisive record in their catalog, it's also absolutely unfiltered, uncompromising, and set up by the artists themselves as the end goal of a mission to get their edge back. The reissue's notes reveal as much. Becker and Fagen are fading in the L.A. sunshine and becoming self-conscious of their songs' diminishing returns: "we switch on the scratchy car radio to soothe our weary psyches, and lo - we are mocked and assaulted by the tinny bleat of our own recorded music, its every flaw hideously magnified, its every shortcoming laid bare." They decide that the SoCal hired hands they've been turning to so far have been siphoning off their brute force, so they swap out future Toto founders Jeff Porcaro and David Paich for a bunch of soul-jazz powerhouses. They brought in funk-break immortal Bernard "Pretty" Purdie on drums, with Dylan/Isleys collaborator Paul Griffin and Don Grolnick, a fixture on the CTI roster, both on keyboards. The result was their fiercest, funkiest record in their entire catalog, a classic that transitioned them from the uneasy company of the yacht-rock smooth to a mean unit that grooved like Stevie for pessimists. Nothin' here but history.

This is not a smooth record. It might fool you for a bit; there are some absolutely frictionless motions turning all the little gears in this piece of work. But as it turns out, nearly all these pop-song novellas are driven not by contentment but by escape -- from one bad situation to another one, assuming you even have so much as a destination. When the psychedelic trade bottoms out, when loneliness requires all your friends to be imaginary, when your go-to option as a fugitive is suicide by cop, when the unmeetable promises of Manhattan beckon you away from home... what are you going to do when the inevitable ripoff that pragmatists know well enough to avoid brazenly trips you up?

Aja gets the accolades, and deservingly so, but its immediate predecessor is everything great about Aja in its first full rush of inspiration -- the bicoastal feel, the inseparable merging of pop and chops -- run through with nearly wall-to-wall examples of their most to-the-bone storytelling songwriting. (Only "The Fez" and "Green Earrings" are lyrically abstract; they compensated by bumping enough that early '90s Ice Cube could rap over both of them.) Their fight-or-flight narratives lead shady fugitives to lawless space colonies on "Sign In Stranger," loner children to ponder the ancient history of art in "the Caves Of Altamira,” an unsatisfied wife to hook up with a hotel gigolo in "Haitian Divorce,” and Puerto Rican immigrants seeking a promised land only to get cordoned off in New York City ghettos and driven to addiction in the title cut. It's a bracing dose of world-weary cynicism, snuck in under the cover of cleverly arranged sophistication and (at least according to the guys with their names on the cover) some the most preposterous sleeve art of the decade.

At some points, it almost threatens to become too difficult to bear, but they save the unfiltered gut-punch vitriol for the very end in that titular closer, false promises of the American dream peeling away in the Copland-turned-sour arrangements. The other eight tracks leading up to it are dark, but darkly humorous, for the most part; when they're not, they're tempered with breathtaking musicianship. Opener and all-time classic "Kid Charlemagne" does both, regarding its Owsley-inspired psychotropics guru and his post-hippie-era downfall with equal parts admiration, envy, contempt, sympathy, and warning; it's endlessly quotable, loaded with double- and triple-entendre ("You are obsolete/Look at all the white men on the street" -- are they talking skin or bricks?), and delivered with an edge-of-panic precision in one of Fagen's sharpest lead vocals (twelve words: "Is there gas in the car/Yes there's gas in the caaaaar") and two vertigo-inducing moments of Larry Carlton's greatest guitar solos. Carlton's serrated heavy rock riffs also make the harrowing cornered-rat freakout of a holed-up criminal in "Don't Take Me Alive" into something weirdly stirring, and when the backup singers come in just before the second chorus -- right under the line "Here in this darkness/I know what I've done/I know all at once who I am" -- it's enough to snatch your breath. And when the vengeance-minded cuckold of "Everything You Did" tries to head off incrimination by telling his significant other to "turn up the Eagles, the neighbors are listening" (a story you might know one way or another), it turns a heated confrontation into a farce -- one that starts with threats and ends on a queasy fascination with just how the cheating played out.

All these densely evocative portraits of America in its post-Nixon hangover -- where the counterculture is spent, creatives have lost themselves, and fantasies have lashed back like bounced checks -- fully established Steely Dan in the mode they're best known for. And even if it's still a divisive record in their catalog, it's also absolutely unfiltered, uncompromising, and set up by the artists themselves as the end goal of a mission to get their edge back. The reissue's notes reveal as much. Becker and Fagen are fading in the L.A. sunshine and becoming self-conscious of their songs' diminishing returns: "we switch on the scratchy car radio to soothe our weary psyches, and lo - we are mocked and assaulted by the tinny bleat of our own recorded music, its every flaw hideously magnified, its every shortcoming laid bare." They decide that the SoCal hired hands they've been turning to so far have been siphoning off their brute force, so they swap out future Toto founders Jeff Porcaro and David Paich for a bunch of soul-jazz powerhouses. They brought in funk-break immortal Bernard "Pretty" Purdie on drums, with Dylan/Isleys collaborator Paul Griffin and Don Grolnick, a fixture on the CTI roster, both on keyboards. The result was their fiercest, funkiest record in their entire catalog, a classic that transitioned them from the uneasy company of the yacht-rock smooth to a mean unit that grooved like Stevie for pessimists. Nothin' here but history.

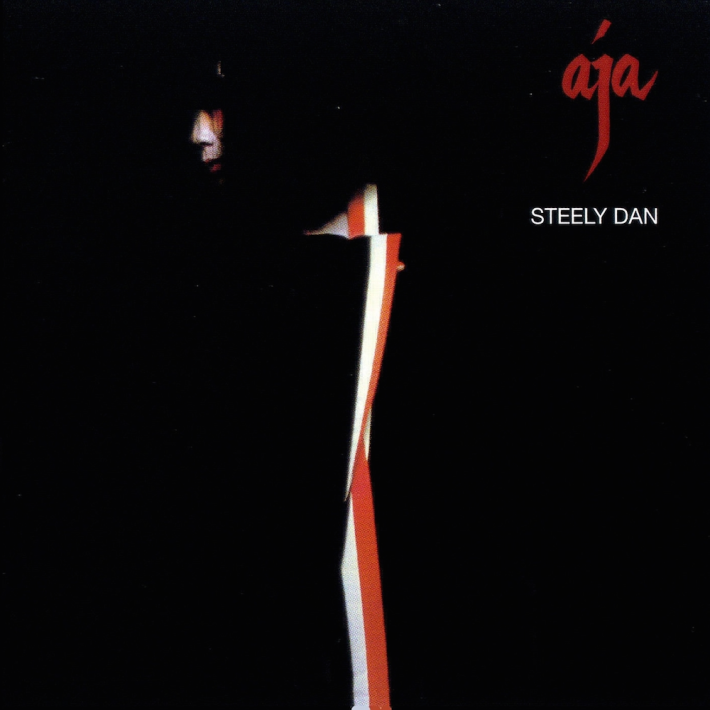

This, of course, is The Big One -- they've got it in the Library of Congress's "culturally important stuff" record crates, it got a lot of people up at MCA walking into Maserati dealerships, and it probably made a lot of CBGB's-haunting New York critics really, really fed up. But it exists, it's ubiquitous, and it's goddamned beautiful, so what can you do. This is where Steely Dan fully redrew the parameters for sophistication in the midst of pop music's weirdest year to that point, and realized that their best eyes have always been aimed at reflections. If the first three cuts on Pretzel Logic were the Dan 101 curriculum for the unwary who wondered if they had a soft spot or two, get a load of Aja's opening trio: "Black Cow," the apotheosis of uncomfortable accidental no-love-lost reunion songs; "Aja," which is almost enigmatic enough to conceal its escapist ambivalence but lets the game slip with a minute's worth of Wayne goddamned Shorter shooting darts through the astral plane; "Deacon Blues," the national anthem of misguided young jet-age dreamers hoping their lives somehow pan out the way the articles in surreptitiously-read Playboy issues promised they could. Then you flip the LP over and there's "Peg.” Sweet Jesus.

So hats off to the inescapable pull of an album dropped when "I Feel Love" and "God Save the Queen" and Marquee Moon were still sending out aftershocks -- that last one instantly adored with an A+ seal of approval from the same Robert Christgau who stamped a B+ on Aja after fighting to overcome his hatred for its "El Lay" trappings. Not to bring up crit-shaming hindsight or anything, just to note that in New York's year of hell -- Son of Sam, the blackout, tenements burning in the shadow of Reggie's Yankee Stadium -- the Dan's Manhattan grime was illuminated by the California sunshine. When that NYC feel isn't explicit -- the "Rudy's" mentioned in "Black Cow" is a Hell's Kitchen institution, still there on 9th Avenue -- it's implicit, high-towering human density swirling around personal foibles and interactions too messy to work efficiently anywhere else.

And every Angeleno session player was guided to lay it down as though they were a couple thousand miles away up in Rudy Van Gelder's studio. The who's-what of this thing doesn't just include session regulars (drummers like Jim Keltner and Bernard "Prettie" Purdie, backup singers including Michael McDonald and Clydie King, Larry Carlton all over the place on guitar), but bonafide jazz contemporaries: the aforementioned Wayne Shorter in that legendary show-stealing tenor sax cameo, Crusaders keyboardist Joe Sample plinking out that chunky clavinet on "Black Cow," Tom Scott tootling out the characteristic electronic woodwind Lyricon riff on "Peg," Lee Ritenour playing sneaky little guitar flourishes into "Deacon Blues" like he's getting away with something. Pete Christlieb got plucked from the Tonight Show Band for his own sax solo -- emphasis on own -- for "Deacon Blues," and wound up impressing Becker and Fagen so thoroughly that they produced and contributed the composition "Rapunzel" to Apogee, his quintet album with Warne Marsh, a year later.

Aja really is this knotty, elaborate thing in both lyrics and music, so much so that when it very briefly gets merely "catchy" and "kind of elusive" -- the loping cocktail-reggae "Home At Last" and the jagged Thelonious disco-funk of "I Got the News" are the orphan deep cuts here -- you get a little breathing room before that latter cut starts getting all hairy with the solos and segues fiendishly into the Plato's Retreat hedonism of every-line-a-diamond dance cut "Josie" ("lay down the law and break it" -- hell yes, even their own rules get thrown out). You can get this record pretty much anywhere and spend a lot of time trying to decrypt its odd little mysteries of mostly disappeared yet still familiar lifestyles. You might not get all the way down to the core, but there's plenty to help string you along if you think you've got a chance to. Like, for instance, the making-of documentary where they acknowledge Lord Tariq & Peter Gunz and chortle at McDonald's isolated vocals on "Peg." Then again, you could skip that -- there's nothing like an album that feels both omnipresent and still more or less just a series of startling out-of-nowhere ambushes.

This, of course, is The Big One -- they've got it in the Library of Congress's "culturally important stuff" record crates, it got a lot of people up at MCA walking into Maserati dealerships, and it probably made a lot of CBGB's-haunting New York critics really, really fed up. But it exists, it's ubiquitous, and it's goddamned beautiful, so what can you do. This is where Steely Dan fully redrew the parameters for sophistication in the midst of pop music's weirdest year to that point, and realized that their best eyes have always been aimed at reflections. If the first three cuts on Pretzel Logic were the Dan 101 curriculum for the unwary who wondered if they had a soft spot or two, get a load of Aja's opening trio: "Black Cow," the apotheosis of uncomfortable accidental no-love-lost reunion songs; "Aja," which is almost enigmatic enough to conceal its escapist ambivalence but lets the game slip with a minute's worth of Wayne goddamned Shorter shooting darts through the astral plane; "Deacon Blues," the national anthem of misguided young jet-age dreamers hoping their lives somehow pan out the way the articles in surreptitiously-read Playboy issues promised they could. Then you flip the LP over and there's "Peg.” Sweet Jesus.

So hats off to the inescapable pull of an album dropped when "I Feel Love" and "God Save the Queen" and Marquee Moon were still sending out aftershocks -- that last one instantly adored with an A+ seal of approval from the same Robert Christgau who stamped a B+ on Aja after fighting to overcome his hatred for its "El Lay" trappings. Not to bring up crit-shaming hindsight or anything, just to note that in New York's year of hell -- Son of Sam, the blackout, tenements burning in the shadow of Reggie's Yankee Stadium -- the Dan's Manhattan grime was illuminated by the California sunshine. When that NYC feel isn't explicit -- the "Rudy's" mentioned in "Black Cow" is a Hell's Kitchen institution, still there on 9th Avenue -- it's implicit, high-towering human density swirling around personal foibles and interactions too messy to work efficiently anywhere else.

And every Angeleno session player was guided to lay it down as though they were a couple thousand miles away up in Rudy Van Gelder's studio. The who's-what of this thing doesn't just include session regulars (drummers like Jim Keltner and Bernard "Prettie" Purdie, backup singers including Michael McDonald and Clydie King, Larry Carlton all over the place on guitar), but bonafide jazz contemporaries: the aforementioned Wayne Shorter in that legendary show-stealing tenor sax cameo, Crusaders keyboardist Joe Sample plinking out that chunky clavinet on "Black Cow," Tom Scott tootling out the characteristic electronic woodwind Lyricon riff on "Peg," Lee Ritenour playing sneaky little guitar flourishes into "Deacon Blues" like he's getting away with something. Pete Christlieb got plucked from the Tonight Show Band for his own sax solo -- emphasis on own -- for "Deacon Blues," and wound up impressing Becker and Fagen so thoroughly that they produced and contributed the composition "Rapunzel" to Apogee, his quintet album with Warne Marsh, a year later.

Aja really is this knotty, elaborate thing in both lyrics and music, so much so that when it very briefly gets merely "catchy" and "kind of elusive" -- the loping cocktail-reggae "Home At Last" and the jagged Thelonious disco-funk of "I Got the News" are the orphan deep cuts here -- you get a little breathing room before that latter cut starts getting all hairy with the solos and segues fiendishly into the Plato's Retreat hedonism of every-line-a-diamond dance cut "Josie" ("lay down the law and break it" -- hell yes, even their own rules get thrown out). You can get this record pretty much anywhere and spend a lot of time trying to decrypt its odd little mysteries of mostly disappeared yet still familiar lifestyles. You might not get all the way down to the core, but there's plenty to help string you along if you think you've got a chance to. Like, for instance, the making-of documentary where they acknowledge Lord Tariq & Peter Gunz and chortle at McDonald's isolated vocals on "Peg." Then again, you could skip that -- there's nothing like an album that feels both omnipresent and still more or less just a series of startling out-of-nowhere ambushes.