There are plenty of reasons the horror and sci-fi and action movies of the late-'70s and '80s have aged so well. There was the self-conscious and shameless cheapness of it all: These were movies designed to entertain fucked-up teenagers, and they prized jolts and cheap thrills and general viciousness. But there was also the '60s-hangover sense that you could cram big ideas into these cheap shells: The future warriors sent back through time to change or preserve the course of history, the vision of New York as a byzantine map of colorful gang territories, the escaped mental patient who turned out to be the true embodiment of unstoppable evil. There were the special effects: Sophisticated and tactile and often genuinely disgusting before CGI came in and gave filmmakers a way-too-realisitic shortcut. And then there was the music. Somewhere in there, directors and composers figured out that synthesizers could create an otherworldly sensibility that orchestral scores couldn't. Louis and Bebe Barron made the first-ever all-electronic score for the 1956 sci-fi flick Forbidden Planet and came away with something unsettling even in a movie with a wooden and straightlaced Leslie Nielsen as the star. By the time Kubrick made A Clockwork Orange in 1971, Wendy Carlos had elevated that feeling to high art. And by the late-'70s, there was a whole generation of musicians whose gleaming synthscapes had changed the way movies sounded, turning them into tense dreamlike reveries: Tangerine Dream, Vangelis, Giorgio Moroder, Goblin, Brad Fiedel, Harry Manfredini, Charles Bernstein. And then there was John Carpenter, possibly the greatest of all of them.

Carpenter started putting together the scores for the movies he directed because it was cheaper than hiring a composer and an orchestra. That sort of low-budget necessity can sometimes lead to great things, and Carpenter's scores are great. His theme music for Halloween might be the all-time greatest piece of horror-movie music, and it's been sampled countless times. His eerie score for Assault On Precinct 13 made the movie's silent, creepy-as-fuck gang armies feel like supernatural wraiths. The absurd dystopian future of Escape From New York, where Manhattan is a walled-off prison for society's dregs, somehow becomes more tangible with Carpenter's ethereal synth theme. When Carpenter finally reached the point where he could make a movie without doing the score himself, it was 1982's The Thing, which I think was his greatest movie. For that one, he hired Ennio Morricone, arguably the greatest film composer who has ever lived. And here's the thing: Without one of those itchy cold-sweat synth scores, The Thing felt like it was missing something. It's a fantastic movie, but a Carpenter keyboard doodle could've pushed it even further. There's a sense of vision and atmosphere in Carpenter's movies that owes everything to his music. Without even meaning to, he left his imprint on electro and rap and drone and techno and house. He helped create a world where a ringing keyboard tone could imply a cold, harsh future. My favorite film scores in recent years, for movies like Drive and The Guest, are the ones that most directly echo the music that Carpenter made years ago. And that sense of vision is all over Lost Themes, the first straight-up album that Carpenter has ever made.

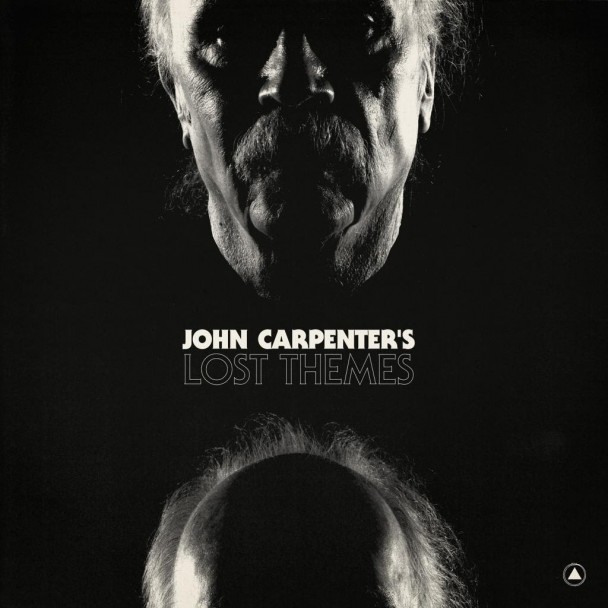

Carpenter is 67 now, and he's essentially retired from directing; his last theatrical feature was Ghosts Of Mars, which turns 14 this year. (Ghosts Of Mars may have been the nadir of Carpenter's film-scoring career. He did the soundtrack with Anthrax and Steve Vai and Buckethead. It was a bad look.) In interviews, he's been saying that he's too old to make any movies anymore, that the process of dealing with studios is too much of a pain in the ass. He seems to smoke a lot of weed. He made Lost Themes with his 30-year-old son Cody, who has a one-man prog project called Ludrium. To hear Carpenter tell it, they made the music on the album for fun, fucking around in Carpenter's basement studio in between video-game sessions. Carpenter's godson Daniel Davies, the son of the second-best Kink, helped out too. It's all improvised, and it was never intended for release; Sacred Bones only got ahold of it when Carpenter's lawyer asked him if he'd had any music laying around. Point is: Lost Themes should not be anything special. It should be the sound of a faded legend with time on his hands and nothing left to prove. It is not that. Lost Themes, as the title implies, sounds like the soundtracks for a few alien-invasion private-eye movies that Carpenter never got around to make in the early- to mid-'80s. It sounds like shapes outside your house at night, like mysterious things moving in the shadows that mean you harm. It's heavy, creepy mood-music of the highest order. It has some motherfucking teeth to it.

In a lot of ways, Carpenter is an icy minimalist. The tracks on Lost Themes are built on heavy repetition, on melodic figures repeated so many times that they get under your skin. But Carpenter is a rock dude at heart. Before he made movies, he played guitar in late-'60s frat-party cover bands, and he met Kurt Russell, the De Niro to his Scorsese, when he cast him in amade-for-TV Elvis biopic in 1978. There's a sense of blues progression to some of the tracks on Lost Themes, and there's a bleary metallic guitar that rears up every so often. The tracks don't just needle away at you, either. They build. There's a dramatic rising action to all of them; they go places. Carpenter has talked about the tracks as soundtracks to imaginary movies, and a couple of times, my wife has walked downstairs while I've been listening to it and asked me what movie I'm watching. Even if he doesn't make movies anymore, Carpenter is still a storyteller, and the way the songs move towards a climax mirrors the way a movie would. The songs establish a mood, and they build from there. I can't remember the last time I heard an instrumental album quite this riveting. These tracks refuse to sit still, and there's an internal logic in the way they ratchet up the tension. It's an album for driving empty city streets late at night, for imagining yourself into a movie of your own life. And it's too bad Carpenter doesn't make movies anymore; you can't help but envision the scenes that this music could soundtrack.

Lost Themes is out now on Sacred Bones. Stream it here.

Other albums of note out this week:

• Title Fight's sad-guitar post-post-hardcore movie Hyperview.

• Mount Eerie's cold, heavy-hearted auteurist lo-fi double album Sauna.

• Bob Dylan's improbable Sinatra tribute Shadows In The Night.

• New Robert Pollard project Ricked Wicky's debut album I Sell The Circus.

• The Staves' Justin Vernon-produced If I Was.

• Nite Fields' stark postpunk debut Depersonlisation.

• All We Are's elegant self-titled retro-funk debut.

• Feature Films' lush, emotive self-titled debut.

• Say Lou Lou's glittering studio-popper Lucid Dreaming.

• Interpol guitarist Daniel Kessler's Big Noble side-project debut First Light.

• Murder By Death's dramatic roots-rocker Big Dark Love.

• Two Gallants' craggy blues-punker We Are Undone.

• Fulgora's death-grind smasher Stratagem.

• Sun Hotel's erudite indie rocker Rational Expectations.

• Kind Of Like Spitting and Warren Franklin & The Founding Fathers' split LP It's Always Nice To See You.

• The punk rock benefit compilation Strength In Weakness.

• Hiss Golden Messenger's Southern Grammar EP.

• S. Carey's Supermoon EP.

• Open Mike Eagle's A Special Episode Of EP.