In 1995, a few months after she released her best album, I saw PJ Harvey play an American football stadium. Alternative rock was firmly entrenched as a business interest by then, and major labels and radio programmers had started seizing on bands -- Candlebox, say, or Bush -- who could replicate the sounds of young America's rock heroes without bringing along their pesky unpredictability or punk-rock baggage. But some truly strange, obsession-forming things still snuck through from time to time. One of those things was PJ Harvey. That day in 1995, she was playing the local D.C. modern-rock station's annual festival, holding down the main stage right between Primus and Soul Asylum. She got to step onto that stage thanks to a sinuous, whispery song sung from the perspective of a woman who drowns her daughter in a river. That day, with absurd heat raging and frat kids moshing all around me on the stadium floor, Harvey looked like she'd teleported in from another, better world.

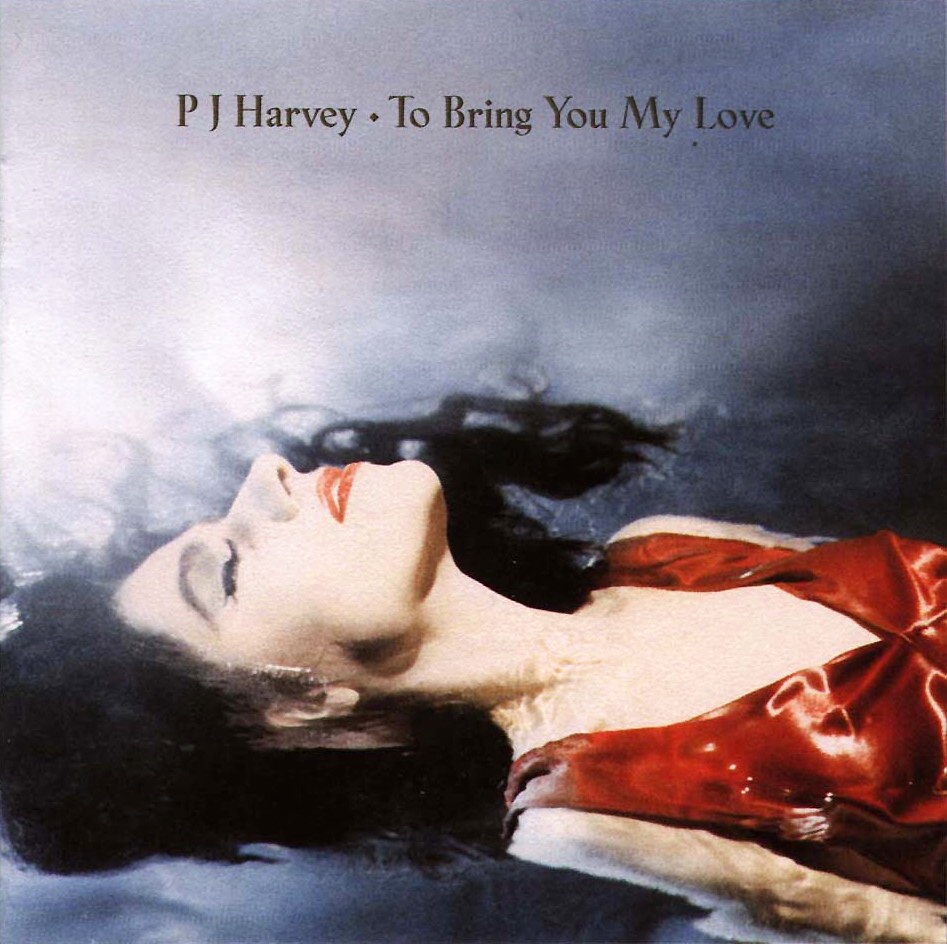

She wore a slinky red ball gown, with a slash of red lipstick across her face that I could see from across the football field, and she moved with a predatory grace. The guys in her band looked like middle-aged professionals, wearing dark suits and fading dutifully into the background. I wished the crowd would fade just like those dudes. I remember ripping crowd-surfers down because they were blocking my view. And I remember a beach ball drifting onto the stage, its presence a blight on the universes that Harvey was conjuring. I was pissed, in the way that only 15-year-old music dorks can be pissed, that some asshole would attempt to interrupt the spells she was casting with a fucking beach ball. Harvey was unruffled. She caught the ball, slowly danced with it for a few brief seconds, and sent it sailing back into the crowd. Since that day, I've probably seen a hundred beach balls bounce onto a hundred festival stages, and none of them have had any effect on me. But the things that Polly Jean Harvey did that day mattered.

Whatever commercial success Harvey had in America was a glorious fluke; it's not like she became anything other than a cult star even after "Down By The Water" went into medium rotation. But this was a time when cult stars threatened to become mass crossover stars, and Harvey was the greatest cult star that we had in 1995. Harvey was already a critical favorite in 1995. Her first two albums, 1992's Dry and 1993's Rid Of Me, had yielded one song apiece ("Sheela Na Gig" and "50 Foot Queenie," respectively) that would get a bit of radio play in late nights. (I know this because I taped both of them off the radio, which was what cash-strapped kids did to obtain music in the pre-downloading era.) More importantly, she'd matured at a frightening rate, going from fully-formed lost-in-obsession howler on Dry to avenging spartan male-ego destroyer on Rid Of Me.

Even taking that into account, though, the leap she took from Rid Of Me to To Bring You My Love (which came out 20 years ago tomorrow) remains staggering. Harvey's original power trio had broken up just after the punishing Rid Of Me sessions, and she reacted by altering her whole sound, persona, and approach. Harvey wasn't the leader of a band anymore on To Bring You My Love. She was something else. She was Patti Smith pretending to be Jessica Rabbit. She was Captain Beefheart fronting Violator-era Depeche Mode. She was Glenn Danzig reincarnated as a film-noir femme fatale. We'd never seen anything like her before, and we never will again.

Sonically, To Bring You My Love is a full about-face from Rid Of Me. Where that album had clanged and scraped, To Bring You My Love floated and sighed. Harvey had assembled a supporting cast that included Bad Seed Mick Harvey (no relation) and John Parish, the childhood friend who would become her musical consigliere in the years after. Where she'd once recorded with Steve Albini, she went with his aesthetic opposite here: Arena-goth guru Flood, who'd helped teach U2 to move and Nine Inch Nails to project. The album's sound was as spare, in its way, as what Harvey had done on Rid Of Me. But this time she went for ominous throb, not punishing crunch.

To this day, I don't know whether the buzzing groove on "Down By The Water" came from a synth pretending to be a guitar or a guitar pretending to be a synth. The sounds just blurred into each other that way. Everything was ornamental: Spanish guitar flourishes on "The Dancer," sustained string-drones on "C'Mon Billy," those Dead Can Dance plinks on "Down By The Water." When Harvey needed to make hard rock, she absolutely could; "Meet Ze Monsta" and especially "Long Snake Moan" are absolute crushers, closer to Zeppelin than the Jesus Lizard or whatever. But she was more interested in taking blues sounds and ideas and pushing them deep into the uncanny -- riding the guitar figure on the title track until it turned into a hypnotic mantra, or straight-up smothering every last sound on "I Think I'm A Mother" (even her own voice) until it sounded like it was about to suffocate.

All that arrangement and production served to highlight Harvey's voice, which has never sounded better, before or since. Harvey is one of the all-time great rock singers because she brought all-conquering strength and soul-ripping vulnerability at the same damn time. She was a feminist icon simply by virtue of existing, and she tore men's souls to shreds with her teeth on Rid Of Me. On To Bring You My Love, she's singing about transcending -- about moving beyond physical concerns, finding the place where love and desire turn mystical. There are moments where the you can feel the physical impact of her full-blooded wail on her voice: the avenging-angel roars on "Long Snake Moan," the sex-yelps on "The Dancer." More often, though, she sounds like a being out of time. That title track, which opens the album, starts out with silence, its rotating guitar figure emerging and getting louder and louder. Harvey sings the same words again and again, first in a monotonal mutter and building to a fevered howl: "I've lain with the devil / Cursed God above / Forsaken heaven / To bring you my love." Every lyric on the album comes with that same mythic weight. And she doesn't just sing those words. She makes you believe them.

Then and now, the song that crushes me the hardest is "Send His Love To Me," with its camel-galloping-through-the-desert acoustic guitar thrum and Harvey's searching desperation escalating eternally: "How long must I suffer / Dear God, I've served my time / This love becomes my torture / This love, my only crime." It's not a song about romantic love -- or, at least, 15-year-old me didn't hear it that way. It's a song about longing, about needing something else, about that feeling where you simply cannot go on with your life as you're living it right now. Harvey's unnamed lover might be the conduit for those feelings, but they're bigger than one man. When things were bad at home back then -- and, without getting too personal, things at home were really bad right then -- I'd retreat into my room in the basement, playing that song over and over, staring off into nothing. I don't know if that song saved me, but it sure helped.

This is usually the point in these Anniversary pieces where I talk about an album's enduring influence, about the impact that it left on the music that came after. I can't do that here. Can you name a single album that built on the foundation of To Bring You My Love? A subgenre that it helped will into being? A culture that it reshaped? I can't. It was a blip on the radar. It came and it went. This makes sense. When an album is channeling those sorts of energies, how can any other artist expect to step in and do anything even remotely comparable? Even Harvey never did again. She retreated further into the foggy ether on Is This Desire?, her next album, and then it was on to the next one, her restless spirit never staying long with one sound or persona. There might be a few echoes of the album's darkness in something like EMA's Past Life Martyred Saints, but I honestly cannot think of another example of an album that does similar things.

Instead, to trace the album's influence, you have to look outside music, to something like the Depression-era British crime drama Peaky Blinders. That's a show about blood and ancient blood rivalries and the weight of ancestral hatreds, and it's a lot of fun. Peaky Blinders isn't one of the all-time great TV shows or anything, but it gets a certain power from the way it plays with visions of old-time blood and fire. That extends to the musical choices. The show uses Nick Cave's "Red Right Hand" as its theme music, and every song on To Bring You My Love appears on the soundtrack during the second season, some of them more than once. The album pairs nicely with Tom Hardy's incomprehensible threat-mumbles and Cillian Murphy's detached bloodthirst.

Or: You could look beyond entertainment completely and just imagine the sight of Harvey on that festival stage, in front of tens of thousands of American teenagers. I was in that crowd, and it left a deep impact on me. I imagine I'm not alone. Now, let's watch some videos.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]