Throughout Madonna's four decade career, she's pissed off a lot of people. Backlash against Madonna has brought otherwise divergent groups to consensus, from Pope John Paul II to Planned Parenthood. As an artist, she has given us so many iterations of herself that she's been able to remain both relevant and agitating across generations.

Her incessant experimentation, whether with her albums or her Instagram, is often irreverent and offensive, but her refusal to apologize no matter how severe the public outrage set a precedent for female musicians. For years, Madonna insisted that her lyrics and sexual expressions were no more explicit than those of her male counterparts, and that most of the criticism she received was rooted in sexism. She never relented in exploring topics of sexuality and gender, and in doing so paved the way for other women artists pushing the boundaries beyond a safe marketing strategy.

Despite her groundbreaking victories in music, she is still getting trolled 30+ years later. But it's okay if you want to body shame her or watch that video of her falling off stage at the BRIT Awards, because Madonna already knows she's flawed. That's her point. She was never America's sweetheart, but she offered the music industry an icon that had been missing for years: a woman with an arc.

There is no better method to explore that arc than assessing her discography, a canon of her varied vocal stylings, cultural samplings, and even spiritual callings. Though her 13 studio albums are often distinct departures from each other in sound and identity, her lack of apology has been a consistent message throughout, reminding us that you have to express yourself if you want to respect yourself.

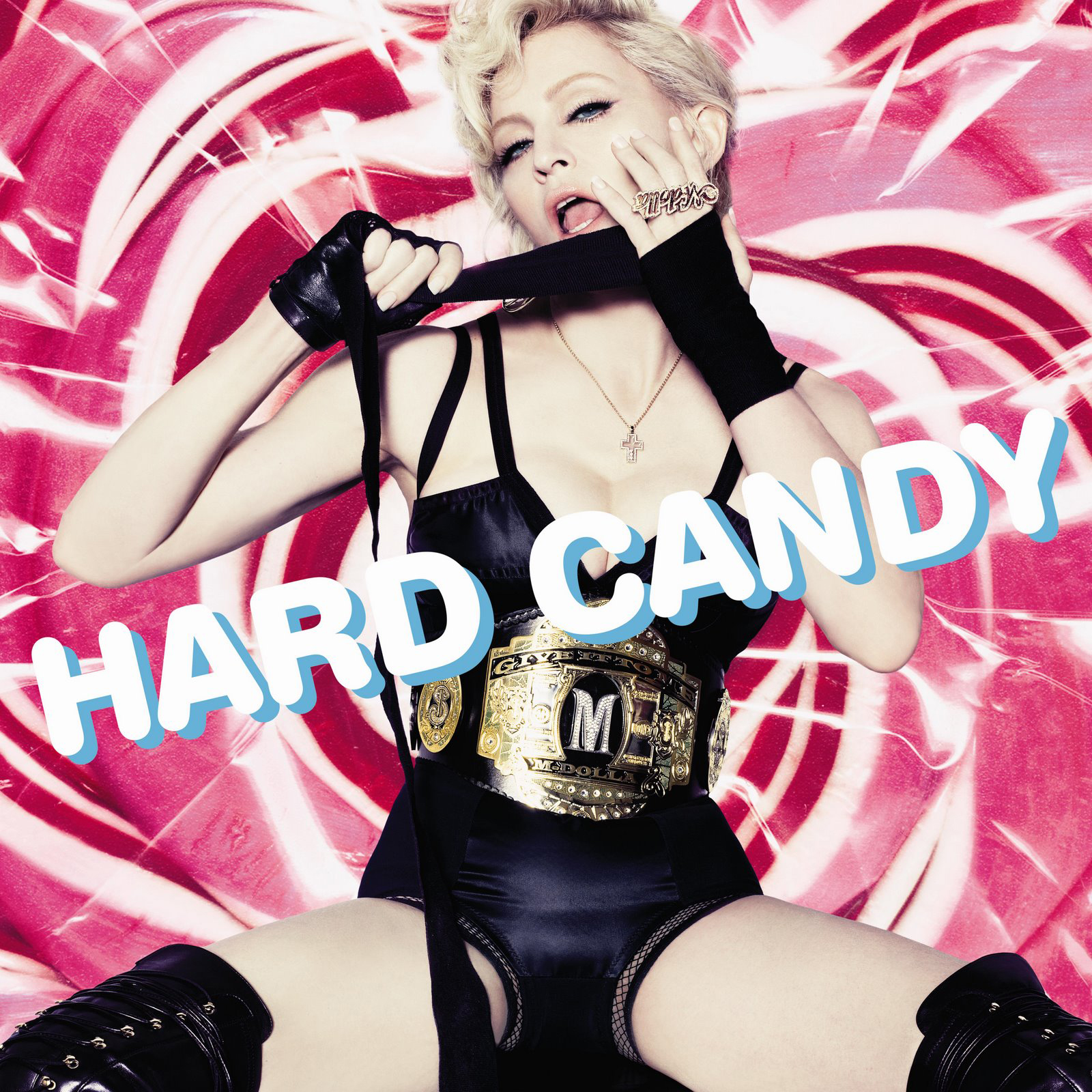

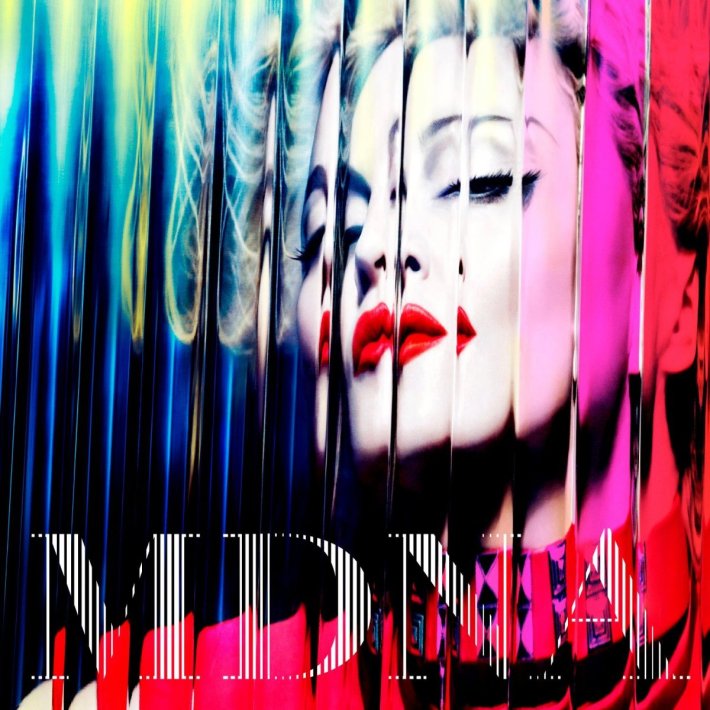

With MDNA, Madonna fully embraced EDM, leaving mainstream pop behind and a large portion of her fan base feeling alienated. Songs like “I’m Addicted” are undoubtedly catchy, but rely too heavily on producer Benny Benassi’s repetitive Euro trance. Madonna barely sounds like she’s a part the action and begins to sound like a distant memory in this transient homage to MDMA. She lends an adolescent timbre to an album that lacks both the forcefulness and the candid sincerity of her lyrics.

While MDNA’s first single “Give Me All Your Luvin’” offered some variety, its real strength rested in the contributions from M.I.A and Nicki Minaj. Throughout the album, Madonna’s vocals serve as an afterthought to the heavier techno productions, making the concept and direction of the album feel even more distant.

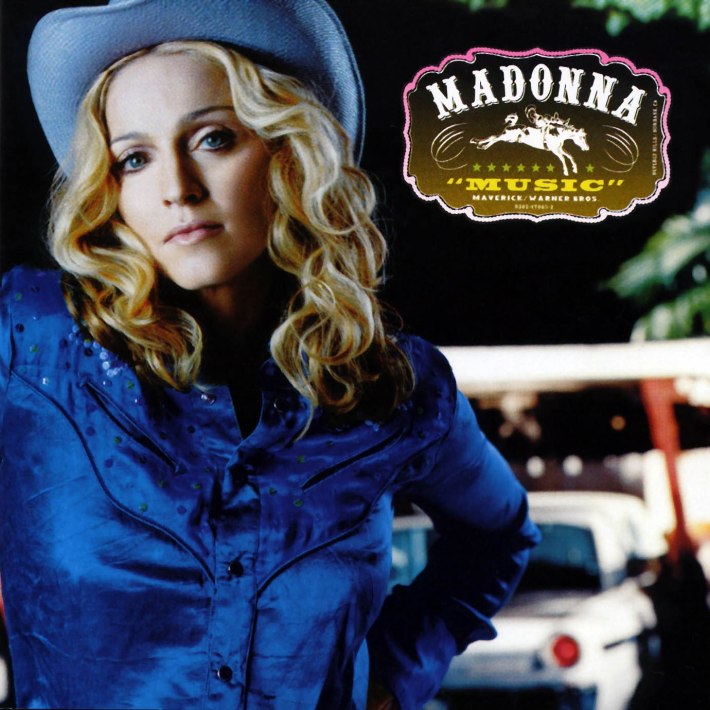

Feeling like the pop scene was oversaturated in the late '90s, Madonna went searching for a more distinctive sound. With the help of French producer Mirwais Ahmadzaï, Madonna samples everything from funk to country, creating what she called “futuristic folk.” Although William Orbit, who produced her previous album Ray Of Light, worked on “Amazing,” “Runaway Lover,” and “Gone,” the album is much less serious than its predecessor, retaining only the electronic vibe. Music became Madonna’s first album to top the Billboard 200 for the first time in eleven years thanks to the album’s playful lyrics and party anthems.

Topping the charts isn’t the only throwback in Music. Madonna shifted into heavier themes with “What it Feels Like for a Girl,” a song whose music video was banned from daytime airplay on MTV. Then-partner Guy Richie directed the music video in a typical Guy Richie style, portraying Madonna on a pill-fueled crime spree while chaperoning an elderly woman. The album is expansive in sound and genre without feeling scattered, and was another example of Madonna’s ability to innovate.

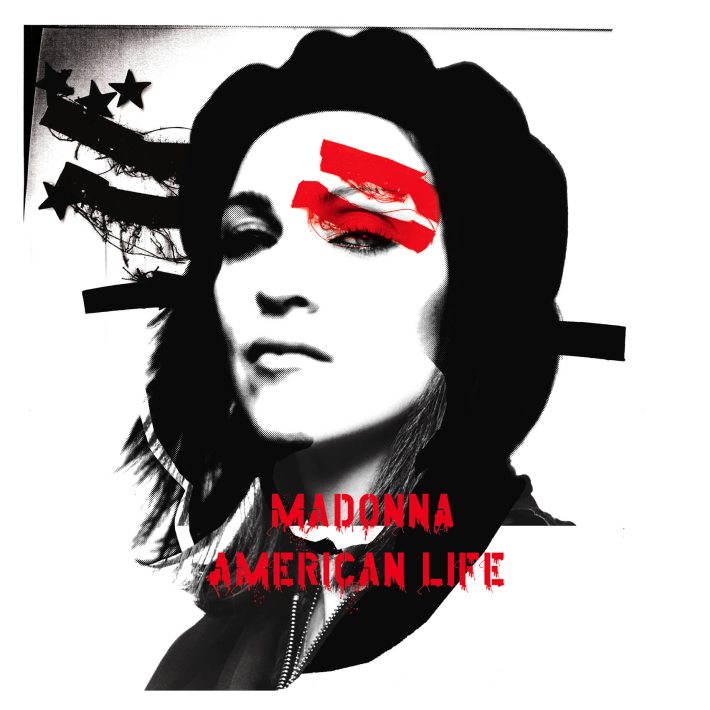

American Life is a subtly drawn concept album that offers political commentary alongside Hollywood satire. After working with Ahmadzaï on Music, Madonna decided to stick with the “futuristic folk” sound that they had created on the previous album. The politically charged lyrics are better interwoven with Nord Lead synthesizers, over-filtering, and country samples. While producing American Life, Ahmadzaï includes a few acoustic guitars, which pair more intuitively with anti-war proclamations, and ultimately gives the album a smooth and consistent foundation.

Madonna also sounds more comfortable in her second attempt at “futuristic folk,” and opens up lyrically in ways she hadn’t since Ray Of Light. The key difference is that although the album is introspective, it lacks the spiritual references that had been present in various iterations across her career. In American Life, she is self critical and equally as scathing of the music industry, but doesn’t indulge us in the higher wisdom she found from yoga/Kabbalah/an ancient text you probably have never heard of because like, it’s super rare.

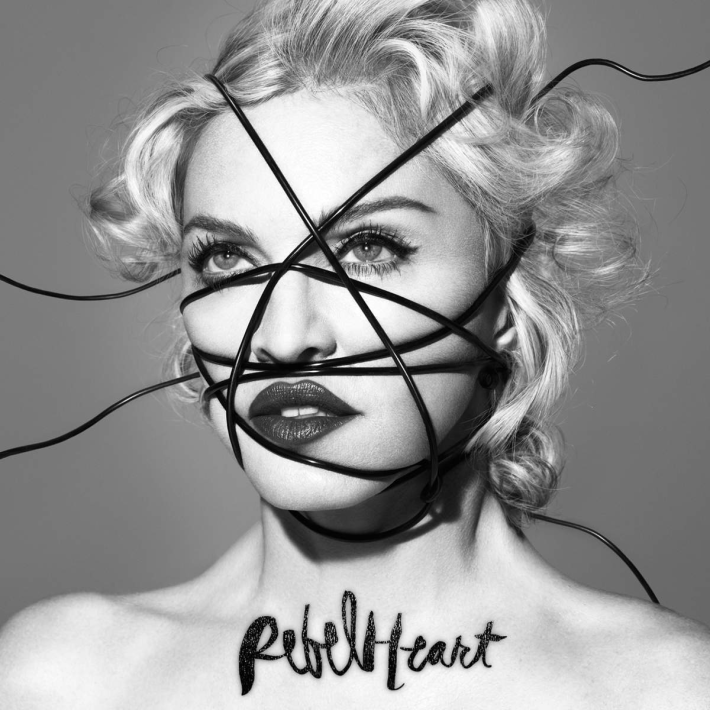

Rebel Heart lives up to its name by pivoting back and forth between rebellion and introspection. The dualistic nature of the album gives Madonna room to dabble with an eclectic amount of influences. “Unapologetic Bitch” creates a dancehall vibe while “Body Shop" sounds like she’s going to Graceland with Paul Simon.

The EDM tracks that dominated her last two albums are still present but not nearly as overarching. Despite Diplo, Avicii, and Kanye on the production credits, the slower, more melodic ballads such as “HeartBreakCity” are the real standouts for revealing a vulnerable side we haven’t seen since the '90s. “Ghosttown” is a synthesized ballad on survival, and recreates a pop-folk blend similar to what she created with Ahmadzaï in Music and American Life.

Madonna revisits the religious themes in both the rebellious and introspective sides on the album. “Joan of Arc” laments her sordid relationship with the media while “Holy Water” describes -- in accurate detail I’m sure -- the taste of her holy water. The album is strewn with lyrics on sin, redemption, and other papal jargon that any Catholic School dropout would recognize. Only this time, Madonna sings with uncouth authority, reminding us that she’s an unapologetic bitch, but not one impenetrable to guilt or remorse. Rebel Heart depicts a rebel with a heart of gold, one who weighed every option and realized there is no nobility in saying sorry.

As discussed earlier, Madonna has angered a wide range of people throughout her career. In addition to Christendom, there have been Orthodox Jewish communities who rallied against her, not to mention Pepsi and the governments of Puerto Rico and Argentina. Yet, there has never been a more controversial Madonna record than Erotica. None of Madonna’s endeavors before or since have received as much backlash and resistance, nearly ending her career.

Maverick Records released this eerie and experimental concept album alongside the coffee table book Sex. The dual release works as a visual and musical ode to bondage, with both media exploring the same themes. Multiple countries banned the album’s airplay and the Papacy went ahead and banned Madonna from entering their realm, but Erotica still managed to debut at #2 on the Billboard 200.

Erotica successfully bounces from house and techno to soul, giving the album an overall ambient quality. Using an alter ego “Miss Dita,” Madonna creates a space of earnest inquiry, which at times becomes more sincere than sexy. Madonna wasn’t afraid to anchor the sex-talk to more serious issues, such as losing her friends to AIDS. Through Erotica, Madonna was able to advocate for AIDS awareness, helping to bring the epidemic into the public discourse.

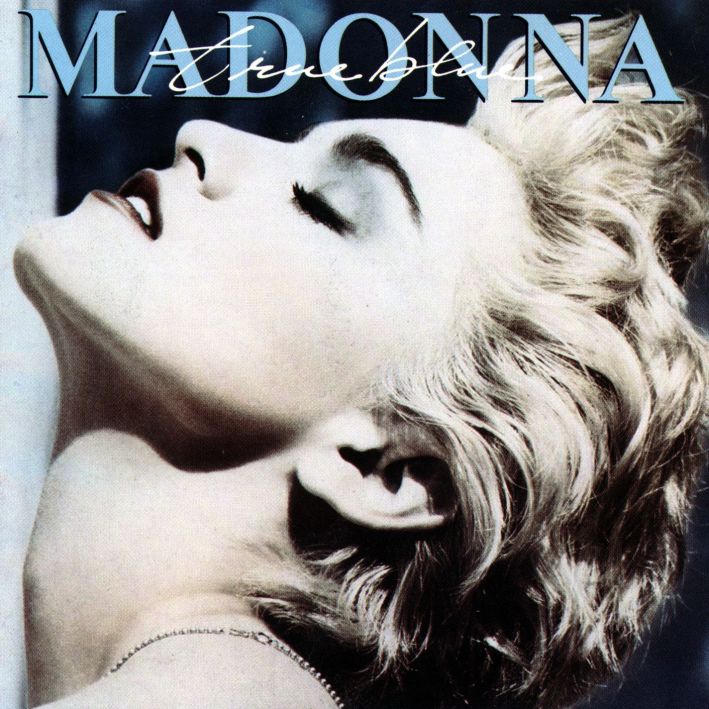

Marking Madonna’s first pivot from her standard high-pitched vocals, the album offers more vocal range and lyrical complexities than her previous two albums. By this point in her career, even her controversies were becoming layered: “Papa Don’t Preach,” the opening track, struck a nerve among conservative groups as well as progressive non profits.

Set to baroque string arrangements and synths, Madonna tells the story of a pregnant teenager defending her choice to keep the baby. She dedicated “Papa Don’t Preach” to the Vatican, assuming her pro-life message would be seen as an olive branch. Instead, Pope John Paul II urged for its boycott on the grounds that it promoted pre-marital sex. Likewise, the song was strongly criticized by Alfred Moran, the executive director of Planned Parenthood of New York City, also fearing that the song encouraged teenage pregnancy. With outrage emerging from both sides, she couldn’t win. The song is about a young girl who made her own choice, but that didn’t seem to work for anybody.

True Blue experiments with different sounds that are well executed as singles, but ultimately sound disjointed as an album. The Latin samplings in “La Isla Bonita” and '60s Motown influence in “True Blue,” are nearly incompatible, and “Live to Tell,” with its personal message of surviving a toxic relationship, feels thrown under the bus when it’s followed by “Where’s the Party.”

There is little doubt that “Papa Don’t Preach” and “Open Your Heart” are songs that established her as a cultural icon, but the album doesn’t live up to the strength of its singles. She dedicated this album to Sean Penn so I’m willing to believe he’s at fault in this.

In the months leading up to Like A Virgin’s release, music critics had already written Madonna off as a one-hit wonder. Then the album sold twelve million copies worldwide on its release, and almost instantly there were courses offered at your campus Women’s Studies Department on how Madonna changed the game for women in pop music. The phenomenon of her fandom was being compared to Beatlemania, as fleets of teenage girls began to dress like the street-smart pop diva and embrace the image of a woman who was sexually confident and unashamed.

This growing fascination with Madonna was further encouraged by the public outrage amongst conservatives, a trend that would start in 1984 and seldom subside. It wasn’t just the subtle promotion of promiscuity that ruffled feathers; Madonna leveraged her Catholic upbringing to include religious references in her music videos that would juxtapose crosses and weddings dresses with candid sexual openness, challenging the virgin/whore complex.

After hearing the album, Tipper Gore and the Parents Music Resource Center placed Like A Virgin on their list of the “Filthy Fifteen,” urging Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) to add a warning label to the record, as song such as “Dress You Up” were deemed unsuitable to minors. Although the moral moms of the country condemned her lyrics and imagery, the album was becoming a focal point for discussions of sex, gender, and religion. Madonna’s only defense was that she had nothing out of the ordinary for male musicians, and the criticism was based in engendered “virginal” expectations she shunned. She was a woman in control of her sex life and her career, and it is that enduring image that has made her so influential.

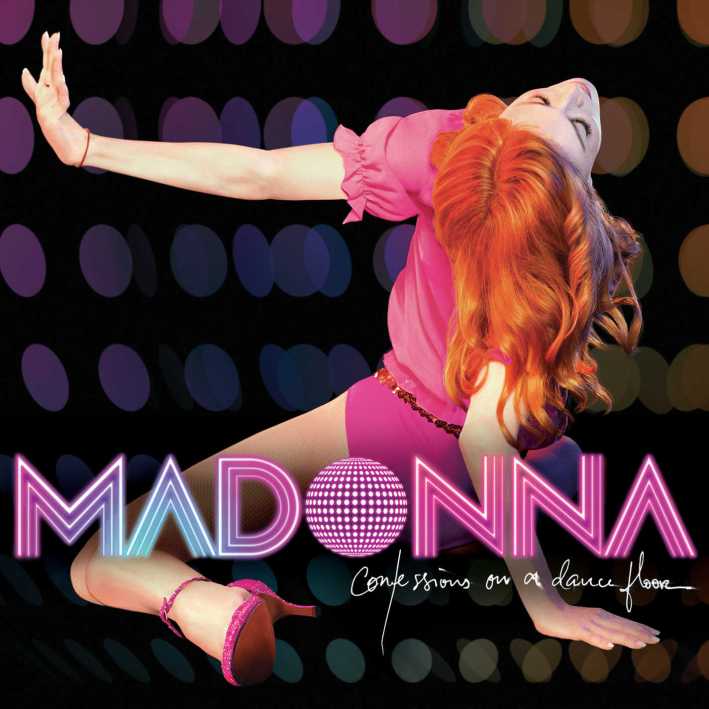

Many of Madonna’s albums are densely packed with divergent influences. Madonna rarely shies away from blending multiple genres and influences onto one album, but unlike its predecessors, Confessions on a Dance Floor derives much of its strength from its singularity. The album carries a story across a steadily growing beat, lending itself to narrative.

Madonna wanted to develop the album as a DJ set, so collaborated with producer Stuart Price to blend each track in sequential order, beginning with an upbeat, fast tempo and progressing towards more complex arrangements. Alongside each track’s consistent climb, Madonna’s lyrics become more intimate, resulting in climactic confessional and heavy bass to go with it. With samples and references to ABBA and Donna Summer along the way, the album reads like a disco-opera.

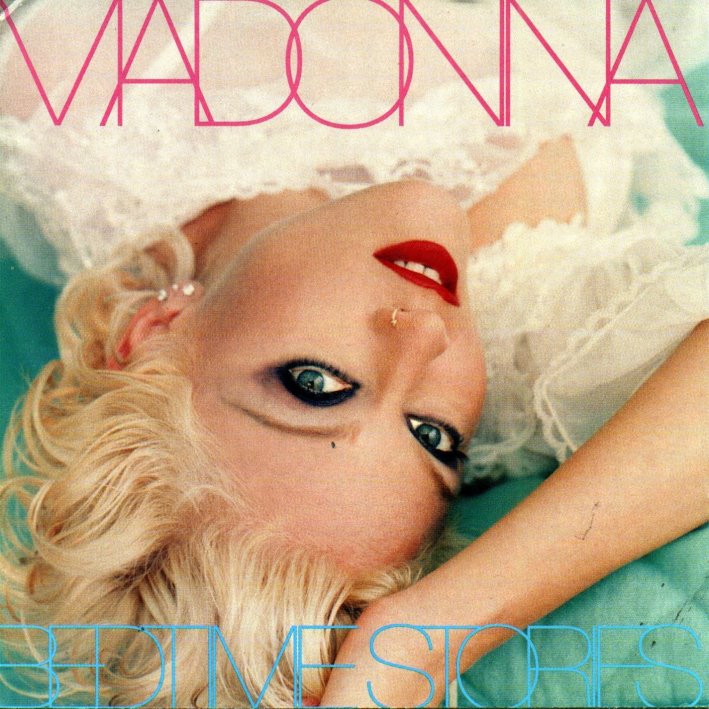

In the months leading up to its release, Bedtime Stories was marketed as Madonna’s return to innocence after the backlash of Erotica nearly threatened her career. The album was anything but an apology. “Human Nature” directly responded to the backlash, asking her critics, “Would it sound better if I were a man?” By openly responding to the problem of women celebrities being scrutinized for their sexuality, she set a tone for how women musicians would later deal with critiques to their sex life.

Although “Take a Bow” was her most successful single on the album, the Bjork-penned title track stands out for being accompanied by one of Madonna’s most beautiful music videos, which is now stored in a permanent collection at MoMA. It also marks an important pivot in Madonna’s image, as it is her first attempt at referencing other religious traditions outside of Catholicism. Her previous album resulted in her banishment from the Vatican, so it’s possible the papal backlash catalyzed a new exploration. Regardless the source, Madonna’s interest in borrowing and reimagining ancient philosophy would be an ongoing journey.

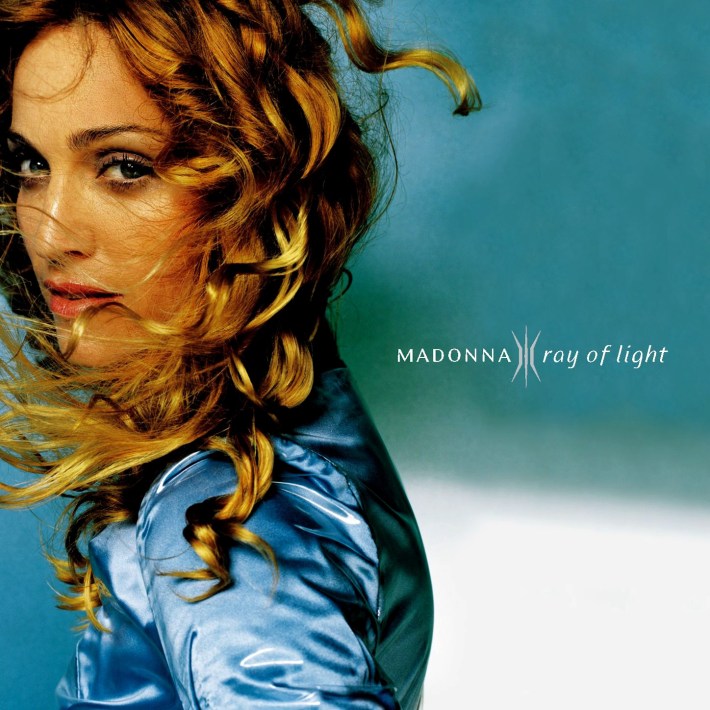

Ray Of Light reestablished Madonna as a groundbreaking artist, thanks in part to the quality of the album but also the context from which it emerged. Boy bands and Disney alums ruled the pop charts in the late '90s, and Madonna’s reemergence onto the scene had a commanding presence over the genre. Its lyrical depth gave the album a sense of maturity, and marked another reinvention in Madonna’s history. Rather than relying on her veteran status, Ray Of Light offered an innovative sound, with many crediting the album for bringing electronica to the mainstream.

Leveraging her voice lessons from the Evita soundtrack, Madonna offers her strongest vocals and breadth of range in Ray Of Light. The album, despite all its experimentation with producer William Orbit, captured a larger audience than previous albums, marking her final departure from teen pop. Ray of Light was her first since motherhood, and born from her earliest studies of the Kabbalah. In addition to references of Jewish mysticism, the lyrics to "Shanti/Ashtangi" are adapted from Yoga Taravali, a Sanskrit text written by the 8th century Hindu philosopher Adi Shankara. When not singing in Sanskrit or bringing underground electronica into the spotlight, the album gives her a vertical for spiritual exploration, lyrically developing ideas on Hinduism, Buddhism, and that old hat of hers Catholicism. The result is her most expansive project to date. With its inclusion of innovative synth technology and production, it is a holistic project that seems to encompass all of her spiritual and musical drifting.

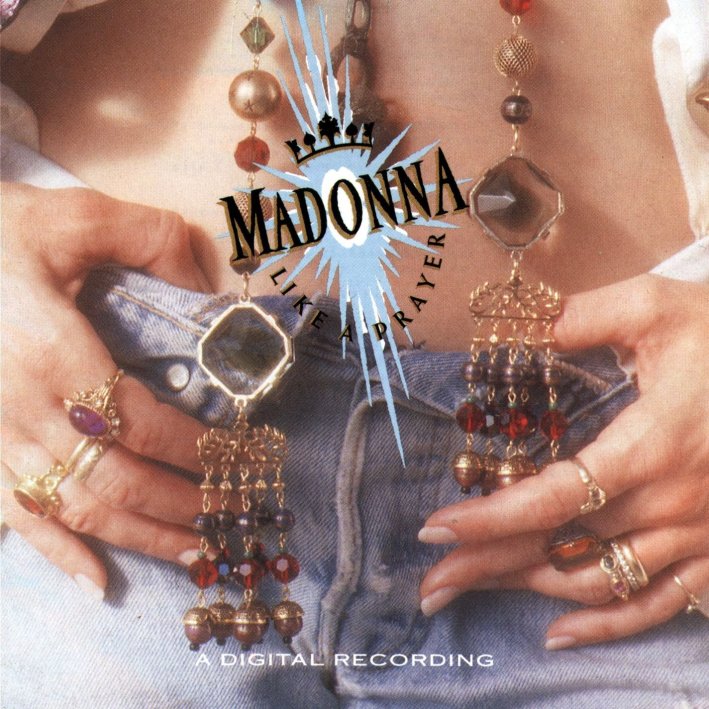

By the late '80s, Madonna’s music videos were an artistic medium in their own right, giving her a portal to further explore themes of sex, gender, race, and religion with imagery. Unlike past singles that backed suggestive lyrics with equally evocative videos, the album’s title track had been considered a graceful move towards spirituality.

When the music video for Like A Prayer finally aired, critics were shocked that the spirited and prayerful hymn to Madonna’s late mother could lend itself to a video that included burning crosses, plot lines of racial profiling, and a fantasy of making out with a saint in the pews. Pepsi immediately cancelled Madonna’s sponsorship contract and took her commercials off the air, while the Vatican one again condemned her lyrics, reminding us that she’s still an apostate.

Similar to Like A Virgin, Madonna defiantly used religious symbolism to explore more relevant, contemporary themes. Despite the eruptive controversy, the album retains its dance pop qualities while conveying her most deeply personal lyrics. “Promise To Try,” “Keep It Together,” and “Oh, Father” are all discussing her struggles of adolescence, often including the effects of growing up under strict Catholicism. This is most evident in the harrowing chorus of “Oh Father,” where she reminds dad “I lay down next to your boots and I prayed/ For your anger to end/ Oh Father I have sinned/ You can't hurt me now/ I got away from you.” She also reveals a history of violence and abuse in her failed marriage to Sean Penn in “Till Death Do Us Part.” and later confronts the issue of AIDS in her memorial “Pray for Spanish Eyes.” Lyrically, she was at her most vulnerable, adding spiritual checkpoints to songs about each major crossroad in her life.

While the title track catapulted Madonna into new levels of controversy, the album’s opus is undoubtedly “Express Yourself.” Not only does the track clearly define the album’s modus operandi, it’s the hymn best equipped to sum up her entire musical career. It is a dance anthem that plays with themes of lackluster romance and the habit of being silenced as a woman, and settles on a resolution of unapologetic noise.