This year, the best story in rap -- and the best story in music, and maybe the best story in popular culture in general -- is the three-way dance that Drake, Kendrick Lamar, and Kanye West have been dancing. They've all been throwing huge shadows over rap for years, and they're all entangled with one another in different ways. And even if they aren't directly, outwardly feuding with one another, they're absolutely on each other's minds. At this exact historical moment, rap doesn't have any one dominant figure. It has these three guys, all quietly fighting to be the one guy. They're watching each other, planning their moves, acting and reacting. It's been fascinating. And it's been this way, actually, for a long time. Drake came out in Kanye's shadow, making melodic woozy electro-emo in the immediate aftermath of 808s & Heartbreak. And then Kendrick came out in Drake's shadow, getting a snarly flickering fast-rap showcase on Take Care and then, along with A$AP Rocky, opening the Take Care tour. Drake started out with robotic cosmopolitan sad-bastard new wave because Kanye made that rap's dominant sound. A couple of years ago, Kendrick was rapping over woozy, drifting synth-strobes because Drake made that rap's dominant sound. And now all three are on pace to release surprise albums within a few months of each other, and it's an exciting time to be following all of them. We don't yet know how Kanye's album will sound; Kanye's made damn good and sure of that. But Drake and Kendrick's albums are both out there in the world now, and they've gone complete opposite directions. They're the odd couple atop the rap heap.

If You're Reading This It's Too Late and To Pimp A Butterfly aren't responses to one another; the releases are too close together for that. But both are distilled aesthetic images of who Drake and Kendrick are, and the two records show just how different these two can be. If You're Reading This is a directly competitive record, one that takes subliminal shots at Kendrick over and over. To Pimp A Butterfly is an album concerned with bigger things, with ideas of blackness and Americanness, and it doesn't spare any words for Drake. (Interestingly enough, though, both have lines about how they took last summer off and how nobody else stepped up to challenge them. It's true in both cases!) But I think Kendrick was thinking about Drake when he made To Pimp A Butterfly, if only because that album is so far outside Drake's comfort zone. It's an insular, conflicted, emotionally fraught, stylistically cluttered freakout of a record, as far from Drake's sparse architectural hooks as Kendrick could possibly get. Kendrick knows Drake could never, ever make a record like this, and maybe that helped drive him to make it.

There's an ambition gulf between the two records. Drake first meant If You're Reading This to be a free mixtape. He may have released it commercially just to get out of his label deal, though it's sold so many copies that it sure turned out to be a lucrative decision. But it's also a retrenchment -- Drake further refining his spacey muffled thud, working with his favorite producers, barely inviting any outside guests to the party. Drake has been sure to point out that it's not his real album, that his real album will come out sometime soon. But that real album probably won't be any more likely to address our own chaotic moment. Instead, its ambitions will likely be of the commercial variety. It'll have bigger pop songs, more famous guests, more songs for the radio. If You're Reading This is a hard and bitter album, an album about being sick of having to deal with the people. It's terse and suspicious and not terribly kind to the women in Drake's life. But it still bursts with hooks and melodic flourishes and cool little production touches, mostly because Drake doesn't know how to make music that doesn't do those things.

To Pimp A Butterfly is something else. It's the album that's been brewing in the lab forever, the one that's been engineered to address our current cultural moment and the state of Kendrick Lamar's eternal soul. Putting it together, Kendrick practically developed a whole new musical language, bringing jazz virtuosos into the studio and rapping over a whole beat CD's worth of Flying Lotus tracks just to settle on the one he ended up using. Kendrick's nearly completely ditched the unearthly beat-demon flow that helped make him famous. Instead, he's adapted slam-poet cadences and rapped in a half-dozen different voices. There are hooks on the album, but they're of the DJ Quik oblique-funk school, and they don't always reveal themselves immediately. There aren't many non-Kendrick rappers on the album, but there are so many voices -- soul legends and half-forgotten neo-soul enigmas and Dr. Dre calling in with motivational advice. It's the album where Kendrick pulls his sound in as many different directions as it could possibly go; it's his Phrenology, his Electric Circus. And it has so many messages that you could spend an entire graduate thesis teasing all of them out. Drake's only real message is "people need to stop asking me for shit."

Even the method of release is different for the two. They both surprise-released their album on iTunes in the middle of the night, but the two surprise releases didn't go the same. Drake's was impeccably planned-out and executed, arriving in the middle of the night with no forewarning. Kendrick already had a release date, but he messily jumped the gun on it, and either Interscope or iTunes fucked up the release royally. At first, only the clean version was for sale. Then, the dirty version showed up late, presumably after many had already paid money for the clean one. Then, both disappeared. Then, both reappeared. For a while, you could stream the album on Spotify, but you couldn't buy it, which probably cost some people some money. The chaos of Kendrick's album even extended to the circumstances of its release.

Even with all those contrasts, though, there are big similarities. These are two albums from two sharp young dudes, only a year apart, who have achieved staggering levels of success and who are suspicious of that success. Drake had a couple of albums to enjoy it before he started fulminating about how these girls are too messy and telling his mother how the nice girl from her gym isn't ready for this life. Kendrick was barely famous before he started freaking about his wealth turning against him, wondering whether he'd end up like Wesley Snipes in his prison cell. But both are in the same place right now: Holed up in their hideouts, locking the world out. Both rely on motherly wisdom -- Drake speaking tenderly to her, Kendrick turning her words into dense aphorisms. They both think reverently of "old music, soul music," as Drake puts it. And they both see their hometowns as anchoring influences.

Kanye hasn't fully jumped into this conversation yet. He's of a different generation, a full decade older than these two. He's less concerned with rapping, more into ideas about fashion and design. He uses ghost writers and isn't shy about it. And he's already two or three fame-freakout albums deep into his catalog. But he is most assuredly watching these two and thinking about what he can do to top them, which different directions he can push his sound. He'll surprise-release his album, just like they did, and it'll be fascinating to see what he does different, what lessons he takes.

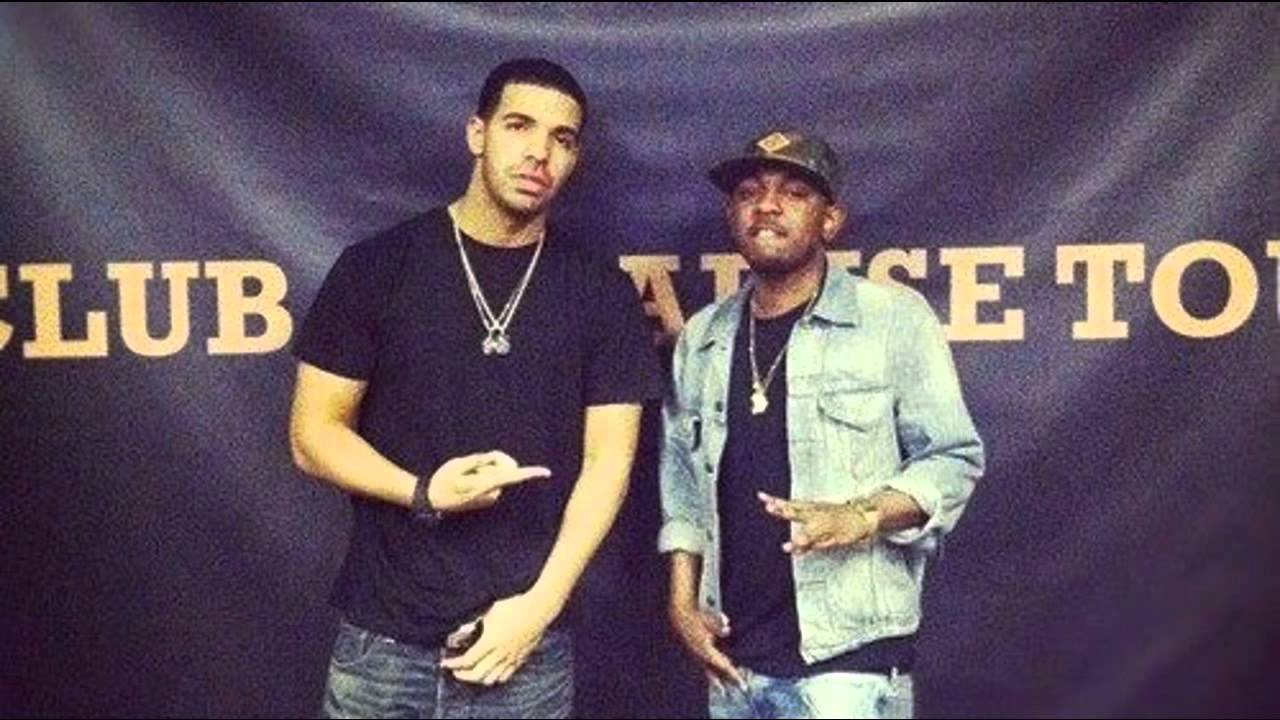

It'll also be fascinating to see what happens the next time Drake and Kendrick's paths converge. The last couple of times the two rapped on the same song -- Kendrick's "Poetic Justice," A$AP Rocky's "Fuckin' Problems" -- they were laid-back shit-talk sessions. They were friends in barbershops, talking about that sundress and the Halle Berry. Then came the "Control" verse and its aftershocks -- Kendrick saying that he wanted to murder every other rapper on record and saying Drake's name, Drake objecting, Kendrick objecting to Drake's objection. They'll probably eventually show up on the same track again; it's how rap works. But what will they be talking about next time?

FURIOUS FIVE

Meek Mill - "Monster"

Holy fucking fuck, this guy! The money turned him to a monster! The money turned his noodles into pasta! The money turned his tuna into lobster! The money didn't turn his rap voice into an electric-shock yelp, because it was always like that, but at least it didn't turn it back! When Meek finds his velocity, there's not a motherfucker who can touch him. He finds that velocity 10 seconds into this, and it never lets up. If you read any news stories about a 35-year-old central Virginia music critic flipping over a semi truck with his bare hands, know that this song was probably involved.

Denzel Curry - "Envy Me"

Curry is a Miami rapper who came up with SpaceGhostPurrp but who rose up as his own voice when SGP flamed out, and he feels like he's ready to take off any minute now. He walks that goon/nerd divide adeptly, sneering at Rich Homie Quan one minute and dropping anime references the next, and his hook is one of the finest fake-Future choruses I've heard in recent days. There's a dark energy at work here, and Travi$ Scott should watch his back. His spot is not safe.

Future Flocka - "Rotation"

So Future and Waka Flocka Flame are a duo now, and that shouldn't make sense. Flocka's combustible energy and Future's robo-blues croon should clash horribly. But on "Rotation," Flocka falls right into the digital churn, and Future ups his energy to "Same Damn Time" levels. Each one could be just what the other needs.

AZ - "Vintage"

This Queensbridge veteran is somehow still in the same deep-in-his-head rapping-for-days zone as he was on "Life's A Bitch" 21 years ago. Here, he attacks a lovely Spanish guitar loop with battle-scarred tenacity, doing that deep-concentration heavy-internal-rhymes QB thing. There's no chorus because AZ doesn't need a chorus.

Memory Man - "PSA (What Does It Mean?)" (Feat. Edan)

Dusty-fingered psych-rap traveler Edan hasn't come out with a new song in years, but here he is, doing lyrical-miracle conspiracy-theory head-blown philosophy like he never left. He's suspicious of Obama, but Obama should still make him Czar of Flute Samples.