In a 2011 interview with Amanda Petrusich for the A.V. Club, the Decemberists' Colin Meloy copped to his band's reputation as a so-called "literate rock band": "I guess it's better than being called an illiterate rock band, because in fact we can all read. But yeah, I'll take that. That's fine. It's English-major rock. I'll wear that on my sleeve."

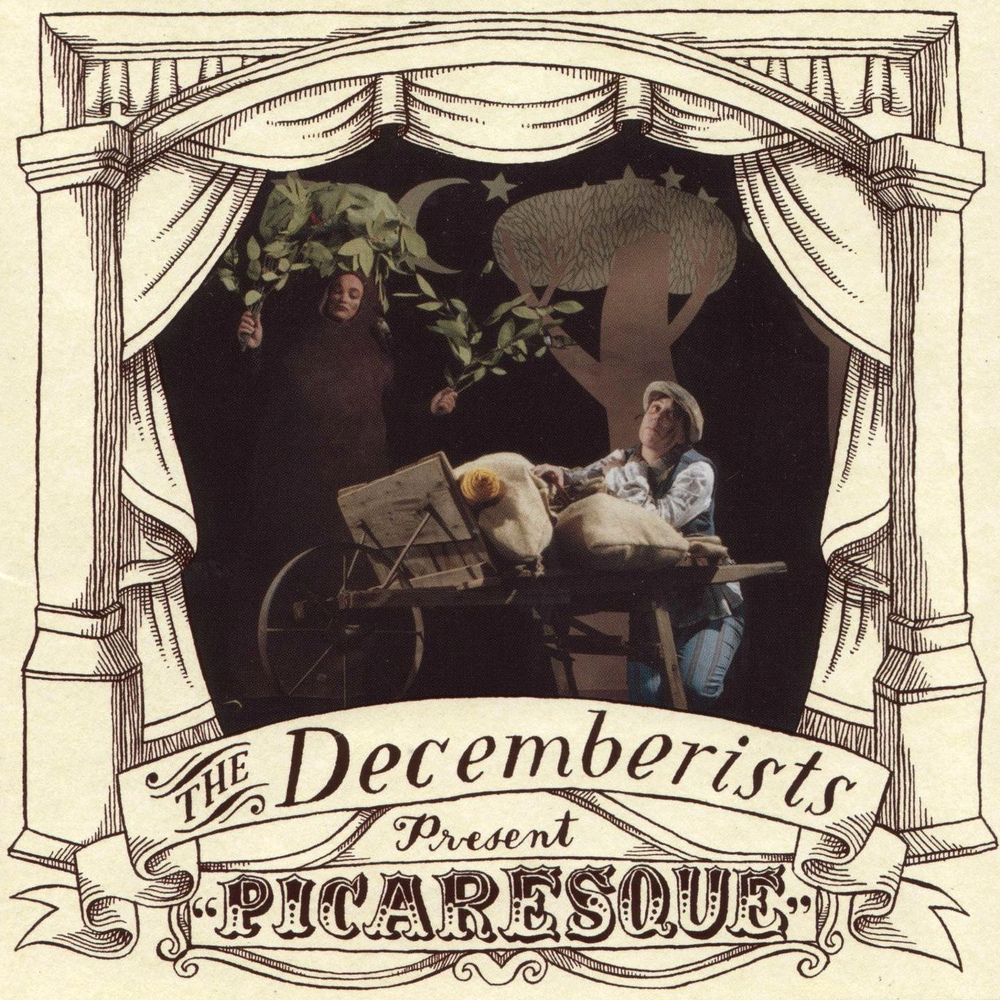

Meloy gave that quote in an interview promoting The King Is Dead, the alt-country return to form that followed the band's fiasco of a rock opera, The Hazards of Love. By then, it was already hard to remember a time that the Decemberists lived close to the heart of the prevailing indie rock idiom; today, it's almost impossible. But 10 years ago, the band released Picaresque, and in a time when the definition of cool was being redefined by a growing number of influential blogs and a legion of suddenly über-informed kids, it seemed as likely as any other indie record to turn its makers into zeitgeist-definers.

It's tempting to call 2005 the year of LCD Soundsystem and Late Registration and mostly leave it at that. That draws a neat line through the 10 years since then and helps explain how we reached the current accepted hierarchy. Among the indie rock kids at my high school, though, it was the year of Picaresque, Sufjan's Illinois, Bright Eyes' I'm Wide Awake, It's Morning, and The National's Alligator. It was the year after Joanna Newsom's The Milk-Eyed Mender and Arcade Fire's Funeral. It was the year In the Aeroplane Over the Sea seemed to ascend to the hushed-tone-classic level past generations of high schoolers reserved for Led Zep IV. (It was also the year some of my friends started calling Franz Ferdinand the best band in the world. 2005 was weird.)

Admittedly, that's all just anecdotal evidence, but even so, it reveals an attitude that few people who consider themselves informed fans of indie music would stand behind in 2015. It places a high value on a dated concept of authenticity based mostly on lionizing musicians who play "real instruments" and sing with their hearts on their sleeves, often through the eyes of tragic historical figures. And yes, it was very often "literate."

Picaresque was the record that was both the most representative of this strain of indie rock, and the most demonstrative of its power. "The Infanta" heralds the album much the way it heralds its protagonist, a royal daughter whose introductory procession is fitted with appropriate musical bombast. Anyone new to the Decemberists can very quickly learn what they're up to after pressing play. There's Colin Meloy's acoustic guitar, strumming away at the center of everything, supplemented as needed by flourishes of horn, strings, piano, accordion, hurdy-gurdy, whatever's needed, flanked by a martial drum beat and electric guitar that help anchor the song, however tenuously, in the rock n' roll tradition.

Then there's the lyrics. The story Meloy spins in his signature nasal baritone is imaginative and full of rich imagery, but his diction makes it easy to see why he's so often been placed in the "English-major rock" ghetto. In a five-minute pop song, Meloy manages to use the words palanquin, pachyderm, largess, baroness (and barrenness), phalanx, parapets, coronets, falderal, chaparral, and coronal. "The Infanta" is a great Decemberists litmus test. Either you heard Meloy sing those words and found the band intriguingly erudite, or you found them utterly pretentious. 10 years ago, it felt easier to stand with the former camp than it does now.

A seismic shift in the value of "authenticity" and what that concept means in indie music has undermined the Decemberists' legacy slightly. Rockists have been widely discredited within the critical discourse, and their acoustic-toting cousins are as likely to ride for Mumford And Sons and the Avett Brothers as the Decemberists, ultimately lumping Meloy's songs in with cheap facsimiles of folk songs repurposed as arena anthems and fodder for Gap ads. The Decemberists still make records, but they're difficult to appreciate in and of themselves because they now feel representative of a dated trend. (Exceptions abound, of course, but even Sufjan Stevens had to wander in a weirdo wilderness for several years before coming back to acclaim for his gently dark folk music, and it took Josh Tillman quitting Fleet Foxes and coming back as the schticky Father John Misty for people to care about his songs, so fuck it, it's a trend.)

Revisit Picaresque in 2015 and its songs come back to life. "The Infanta" still charges ahead with regal bluster; "We Both Go Down Together" is still sweetly tragic; "The Bagman's Gambit" and "On the Bus Mall" will still leave you an emotional wreck. The Decemberists even manage to clear the bar on the self-consciously fun songs, songs that would likely sound silly if a new band attempted them. "The Mariner's Revenge Song" is a rollicking sea shanty that's also a shockingly effective bit of storytelling, at once blasphemously Biblical and reverent of the great tradition of the Irish drinking song. In fact, no band's shadow looms as large on the tunes here as The Pogues, whose own shamelessly affected take on the hip alternative music of their era made them as many fans as vocal opponents. Rum, Sodomy & the Lash is an especially huge influence; the lovely, heartbreaking "On the Bus Mall" might be the best song on Picaresque, and it's essentially an adaptation of "The Old Main Drag."

The Decemberists will most likely never be a cool band again. Their music is less idiosyncratic than it once was, despite Meloy's ever-present yowl still directing the proceedings. Their music also isn't as good. Their two-album peak of Picaresque and 2006's epic Jethro Tull/Neutral Milk Hotel mashup The Crane Wife remains the absolute pinnacle of this kind of rock music. Their recent retreat to a gentler folk rock sound has neutered a lot of what made those albums so inspiring. But listening to those great records is still as rewarding as it was when they came out, and it offers a thrilling exercise in speculative fiction: What if things turned out differently? What if, for more than just a few thousand English majors, Picaresque was Led Zep IV?