One Of Those Treadmill Guys.

Regardless of how many years he is eventually blessed to squeeze out of this corporeal existence, this is the epitaph OK Go vocalist/guitarist Damian Kulash is absolutely certain will be carved into his tombstone.

And he might very well be right.

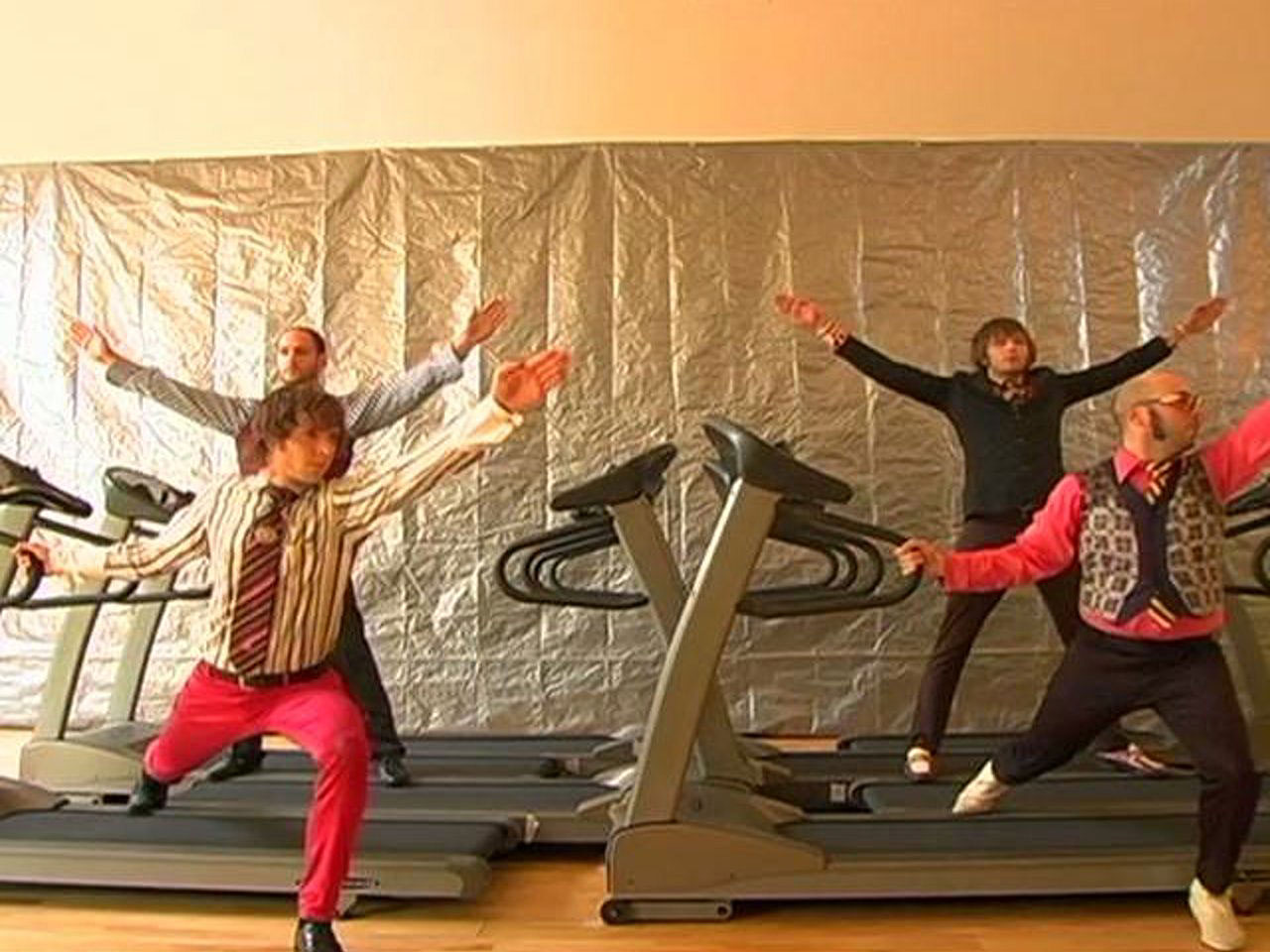

After all, the Los Angeles-by-way-of-Chicago indie rockers' 2006 video featuring an exuberant for-real-swagger-meets-pure-goofiness four-man choreographed dance across four running treadmills to the tune of the garage-y clang 'n' banger "Here It Goes Again" has been viewed tens of millions of times and is, like so many clips in band's vast, endlessly inventive videography.

The story of OK Go's evolutionary transition from deft, effortlessly hip earworm factory to unwitting Charles Darwins of the digital multimedia age -- i.e., dudes whose work reveals the interconnectedness of seemingly disparate elemental building blocks that roils just below the surface -- is not, however, a tale of clever Brave New World marketing and/or evil-genius exploitation of one and zeroes regaining some semblance of the pre-internet music industry glory days.

Yet neither can we quite label it the triumph of art over commerce -- true, in many respects, yes, but also overly reductive.

Rather, what OK Go helped nudge our now perpetually in-flux culture to transcend was certain antiquated preconceptions about the rigid boundaries of production and distribution, which limited -- and, of course, continue to limit -- potential. The band was like Toto tugging back the curtain near the still bellowing, blustering major label behemoths to reveal a few lever-pullers desperately trying to maintain a façade of power and prestige -- or at least hold onto jobs that increasingly lacked a defensible rationale.

For those who believe this is all hype and hyperbole -- a cohort that, admittedly, might include humble and bemused members of the band itself -- consider this: Back in 2006 OK Go's then-label Capitol dumped "Here It Goes Again" onto stupidvideos.com without consulting the band.

This was the level of expertise and respect granted.

In the ensuing years OK Go videos have screened at the Guggenheim, the Museum Of The Moving Image, the Edinburgh International Film Festival, the Los Angeles Film Festival, and more.

On the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the band's completely unintentional instant classic clip for "A Million Ways," we talked to Kulash about a bunch of things including the marriage of sound and image, the evolving business of music, Ian MacKaye as loan officer, what it is like to testify before Congress, and the complete incomprehensibility of viral success.

"Mostly we stumbled into this whole thing backasswards," says Kulash. "We weren't trying to make films -- we were just trying to put on a good show."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

STEREOGUM: It's the tenth anniversary of your band's "A Million Ways" video, which was sort of this seminal moment in what came to be known as the cultural phenomenon of viral videos. What do you recall about putting that clip together?

KULASH: Well, we actually didn't think of it as a video at all. To go back a little, in our very earliest days in 1999 -- we'd done a few shows and had recorded one demo for one song -- a local public access show in Chicago asked us if we would play. We were like, "Sweet! We're a band that's barely been together a few months and we're going to be on TV!" And then we learned, of course, they didn't have the technology to actually record bands, so we'd have to go on and lip sync. Being a self-respecting band we didn't want to lip sync, but we said, "Fuck it -- we've already agreed to do it and if we're going to do it, let's swing for the fences."

STEREOGUM: And what did "swinging for the fences" entail?

KULASH: We spent a week coming up with a ludicrous boy-band routine. I was working as an engineer at NPR at the time, so I invited all the hosts of the big Chicago public radio shows -- Peter Sagal and Ira Glass and Gretchen Helfrich and Jerome McDonnell -- to be our pretend backing band, just figuring they're people whose faces no one ever saw and it would be a weird, fun inside joke. So we basically did this strange little art project, and that was the end of that. Or so we thought. [The next year] Ira asked us to be his backing band for the This American Life fifth anniversary live tour -- and he really wanted us to do our dance on stage. We said, "Ira, you can't hear a dance on the radio." He was like, "I don't care. I just want you to do it." So we revived the dance and it was this really odd moment where this thing that was sort of a piss take in the first place, [and which was] so unexpected of an indie rock band, kind of broke the tension between the audience and the stage. It took us awhile longer to realize we should make that part of our normal live show -- thick in the skull, I guess -- but eventually we did.

STEREOGUM: I know you grew up in D.C. and were heavily influenced by the Dischord scene. Obviously one of the things Fugazi and those post-Fugazi D.C. bands strived to do was change the punk rock paradigm at shows from a violent explosion to something closer to joyous release. OK Go does a very different thing, but I'm curious if you feel like coming up in that scene made it more comfortable for you to behave in a way so unexpected for an indie rock band?

KULASH: In terms of doing something as ridiculous and self-effacing as dancing like a boy band on stage? No. I think Fugazi and the army that followed them were vastly more self-respecting than us! But in terms of having a show that was, on the one hand, totally all-consuming and immersive as a performance, and, on the other, completely transparent about the fact that it was being done by somebody just like you -- that's an idea that really affected me. I grew up in the era of Nation Of Ulysses, and, obviously, Ian Svenonius is this unbelievable showman going fucking insane on stage, but after the show he would totally be like, "Um, yeah, of course I'd love to listen to your cassette tape demo." Shudder To Think -- I worshipped them. There was one year I saw them twelve times. I was that fucking annoying mega-fan who would walk up to them after shows and ask all sorts of questions, and they were just nice, normal dudes. That's where I came from, you know? Simple Machines printed that booklet on how to put out seven-inches and that's what got me started putting out my friends' records. When I wanted to move from seven-inches to CDs, I walked up to Ian MacKaye's house and asked him for a loan.

STEREOGUM: You did?

KULASH: Yeah, absolutely.

STEREOGUM: And what was his answer?

KULASH: Uh ... Okay.

STEREOGUM: Seriously?

KULASH: Yeah. His speech was hilarious. He was like, "I don't do contracts, but I have five thousand dollars I loan out to make other stuff happen in D.C. So if you don't pay me back this twenty-five hundred bucks, you'll be the kid that basically sinks this whole part of the D.C. scene. Do you want to be that kid?" No sir!

STEREOGUM: Wow. What a crazy experience.

KULASH: Yeah, I had to show him a budget for how I planned to produce and promote the thing. I remember I wrote a-d-d instead of a-d for ads, and he was like, "What's this? You changing addresses? You going to add and subtract something?" Giving me shit for having bad spelling!

STEREOGUM: So it sounds like the influence of the ethic outlasted the sound for you.

KULASH: The difference between loving the D.C. aggression and [OK Go's] Cars and Elvis Costello beginnings was essentially the difference between me at 17 and me at 22. Aesthetically, the fun of doing these dances wasn't at all Ian MacKaye-inspired, but what's interesting is you can kind of find similar themes running through both. You know, you see Ian Svenonius up there doing what he does, but you don't actually believe he's James Brown. And that's kind of why you love it.

STEREOGUM: So anyway, you'd incorporated the public access/This American Life dance into your live show ...

KULASH: And by the time our second record came around we knew we liked that part of our set and wanted to keep doing it, but didn't want to end on a song from the first record anymore. So we were like, "I guess we need to come up with a new dance?" We were still on a major label at the time. Our first record had been big enough to not drop us, but not big enough to really promote or fully fund the second one. Which basically means we were on the very long un-monied leash out in the wasteland that is major labels -- you know, you're either in their big cycloptic gaze or you are not. We were not. But it didn't cost them much to keep us there, and there was still a chance something might happen, so they paid for the record and gave us a small budget for a video. We got [Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind director] Michel Gondry's brother Olivier onboard -- he's done a lot of the graphics and computer-y side of Michel's stuff -- and we made what I think is a pretty decent video for what the label thought the single would be. Everything was going along to major label plan. We're just sort of in the middle of the pack somewhere. That was our video. That was how the whole thing was supposed to go.

STEREOGUM: But that's not the way the whole thing ultimately went.

KULASH: Right. Completely separate from the label stuff, we enlisted my sister, who was a professional ballroom dancer at the time, to help us come up with a new dance for the end of our show. There was no way we could top that original ridiculous dance ourselves -- that was kind of the beginning and end of our choreographic acumen. She was living in Orlando and we flew her out to L.A. She spent a week in the house and we came up with the dance routine that became the "A Million Ways" video. It was really only meant for the live show. A couple weeks later, though, we heard from a person who had a friend who was a make-up person for Michel Gondry that he was about to make this huge incredible choreographed video for some young upstart rapper named Kanye something and we were like, "What? But we're the fucking dance band!" So we actually filmed that clip for an audience of one -- Michel Gondry -- we wanted him to understand he had to make the dance video with us.

STEREOGUM: Did he ever see it?

KULASH: As far as I know, no. But the resulting clip was the kind of thing you send to your friends -- Look at this stupid thing I made. So we did that. And someone we sent it to put it up on iFilm, which was the reigning video sharing site before YouTube ascended, and within a couple months it had been downloaded three hundred thousand times.

STEREOGUM: Whoever uploaded that video ... you owe that person a pretty big debt of gratitude, no?

KULASH: Absolutely! When we realized this was happening we started burning DVDs of [the clip] and giving them out at shows. "Here -- put this online somewhere." That's around the time we stopped looking at it as a weird artifact and realized it was actually a video.

STEREOGUM: Kind of a happy accident that opened up a lot of doors you maybe weren't knocking on.

KULASH: I've said it in far more pretentious ways than this before, but Tim and I have been friends since 1987 and making stuff together the whole time. The band obviously is sort of a conduit for all of that, but in the almost thirty years of our friendship it has been art and videos and songs and performances and whatever else. Most creative people I know sort of live that way. The internet just provided a home for all of that stuff at what was just a very lucky time for us. In the five years that the band existed before that video happened we made tons of little short homemade videos and we made tons of weird art projects for our friends. The difference is we never thought of them as things that would surface or that would be part of our allowable output.

STEREOGUM: In [Craig Marks and Rob Tannenbaum's] great oral history I Want My MTV, they spend a lot of time delving into this idea that there was this Wild West moment in music videos where a sudden need for content outpaced the utility of corporate controls and all this insane, surrealist, adventurous stuff was made for a few years until the gap closed and MTV had more at stake monetarily and "video director" became an actual career and there was less of a need to humor more eccentric artists. Is the internet a place where something like that moment in time is happening again?

KULASH: Partly, sure. Most of what we thought of as music throughout the twentieth century was a very stable because there was such a robust economy around it. Music was whatever you could put on a twelve-inch piece of plastic. And later a five-inch piece of silver plastic. It doesn't matter that a hundred years prior to that recording didn't exist and music was this ephemeral experience you had to be in the same room with someone else to make happen. All the stuff that surrounded that creatively was promotion, but that was the commodity -- that's what we grew up with music as conceptually. And, to me, it seems the internet has done a very good job of destabilizing that stable idea and reminding us how arbitrary those definitions are. It used to be that film was acetate and music was vinyl. We all know the difference between our eyes and ears but both [mediums] included visual and aural elements always: It's been a long time since silent films and I can't remember a single pop musician dating back to Elvis or Dizzy Gillespie who you can't imagine visually. I mean, when I hear a Beatles song I could tell you what haircut they had at the time. Now that everyone makes ones and zeroes there isn't a functional difference between what I make and what someone programming for the Xbox makes or what someone writing for Stereogum makes. We're all turning in our quote-unquote "content." And we all shudder at being placed in that disgusting box because we would like to think of the things we make as inspired and artistic. But at the end of the day we're using the same tools and maybe just creating different types of experiences ... [T]he things that inspired us to make stuff were not necessarily related specifically to music. Like, reading David Foster Wallace was more inspiring to us than watching another music video. Just getting inspired to make shit and having that as your outlet was just sort of like, "That's what's here. That's what in front of us."

So having said that pretentious thing I don't think of it as, "The internet has allowed for a wild west in music videos!" I think of what is happening as way more exciting than that. Are you on Instagram?

STEREOGUM: Yes.

KULASH: Do you follow The Fat Jewish?

STEREOGUM: No. I'm guessing I should?

KULASH: Yes. You should. He is really funny. He's an Instagram celebrity, millions of followers. His whole career is posting small, funny pictures. That format, previously, just literally did not exist. The types of jokes and little things we may have all emailed each other ten years ago -- there's an actual forum for that now, and it's art in its own way. And, from what I can tell, amusing people by Instagram can be a pretty substantial career. Comparatively, making a music video on YouTube is an old school super traditional thing to do.

STEREOGUM: So you do "A Million Ways" and it garners all this attention you weren't expecting. But now you are aware that people are paying attention. Did that change how you looked at your own art and process?

KULASH: Of course. But not in a negative way. More like, "If we can make a video by accident, we should see what happens when we make one on purpose..." I remember we were at LAX about to fly somewhere and I called my sister to tell her we taped the crazy dance she'd come up with and now it was on the internet and had been downloaded hundreds of thousands of times. In 2005 downloading videos wasn't a totally ubiquitous thing and our assumption was we had a new fan base not of rock n' roll people but, like, IT guys. Which I sort of preferred to tell you the truth -- they don't care what's on the radio, they found this thing we'd made, and they chose to like it. So we thought we'd be making the next thing for those same exact people. So we went to my sister's house for ten days and talked about making the next video on a merry-go-round or maybe sets of stairs before eventually deciding on treadmills. My brother in law found a guy we could buy treadmills from and return them at eighty percent of the price. You can't rent them so ... that was a plus. And we made up this thing. Out initial instinct once it was done was, "It's probably too similar to the last thing and pretty goofy -- let's just let the rock n' roll record do its thing, let's keep touring, put out the label-made video, and when this is all done we'll give it away to tide people over until the next record."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

STEREOGUM: And then?

KULASH: And then we were playing in Moscow and our guitar tech goes, "Guys, your video is online." It turns out Capitol, our label at the time -- their idea of a big premiere for this was to put it on stupidvideos.com. It was like, "Really?" Luckily, we were in Moscow and could get it taken down before the U.S. woke up. Then we put it up ourselves on YouTube where it got 800,000 hits on the first day. Which was insane. We thought it had to be a misplaced decimal point. And then all of a sudden the label cares, and we're getting a Grammy, and we're at the VMAs -- a very quick whirlwind and now the cycloptic eye is on us. For a few minutes that was awesome and then it was like, "Oh shit. This is us now. Our tombstones will read: One Of Those Treadmill Guys." Any big hit has that problem -- "Video Killed the Radio Star," you know? -- but especially one that features dudes in tacky suits jumping around on treadmills.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

STEREOGUM: This amazing bit of serendipity and success comes along, but you didn't want the music to get submerged in this other aspect of the art.

KULASH: Here's the thing: You can either go full Radiohead on the song and say, "We're never playing that again. We're way cooler than that and sorry we did it." Or you can try to figure out what made it work from a larger perspective and embrace that ... No matter what you think of our band, our videos, our trajectory, whatever, most bands yearn to establish the outlets to allow them to do what they feel like doing. The narrow path through the label system isn't narrow anymore -- it just doesn't exist. We were just really lucky to be band of old friends making all this shit together perfect fit for a much more amorphous cultural distribution.

STEREOGUM: The whole thing is so beautifully uncontrived.

KULASH: We get asked all the time about our keen, shrewd marketing savvy -- people don't understand there's no way that could happen. There are these agencies that make tons and tons of money selling the idea that they know how to game the internet -- that this is all a cold, cruel science -- but the real world just never works that way. There are fewer gatekeepers now. Now, on the downside, that means there are fewer people to pay you and to make sure the system is solid. But it also means you don't have to try to write the song that get you through the star-shaped hole of the label system and then the square-shaped hole of radio and the diamond-shaped hole of MTV until you've gone through so many holes that you have something that sounds exactly like everyone else.

STEREOGUM: You've been an outspoken supporter of "net neutrality." You must be pleased with the recent FCC vote.

KULASH: Uh, fuck yeah. I'm elated. It's great, even if the fight is far from over.

STEREOGUM: You testified before Congress as well. Was that a surreal moment for you?

KULASH: Extremely. People think it must be nerve-wracking to speak on stage in front of a large crowd of people. The truth is, it's usually inverted. Like, the smaller the crowd, the more nerve-wracking it is. Five thousand people is just a mass of people. A hundred people, you can see every sweating face in the room. Twelve congressmen is fucking scary as shit. It was very intense.

STEREOGUM: It must be gratifying, though, to have something you created as an artist provide this platform for you to advocate for things you believe in on such a huge scale.

KULASH: Very much so. And we're straight back to the D.C. roots again. The same women who put together Simple Machines -- Jenny Toomey and Kristin Thomson -- helped start a musicians policy group, and that's how I got involved. Jenny called me up and said, "I remember when you used to send us postcards asking for advice when you were sixteen years-old. I could really use your help with this right now." I was honored to do it ... Actually, I couldn't believe when I got to Chicago how aggressively disassociated politics and art were; that saying something you believed about an issue might be seen by an audience as alienating rather than a natural course of affairs. The music I grew up on in D.C., if it wasn't at some level political, there was a problem.

STEREOGUM: When you conceptualize videos like these, does it open up new avenues for you to explore your own songs in ways that you might not otherwise?

KULASH: There are kind of two answers to that question. First, with respect to individual songs, what changes a song most is playing it over and over again live. It is always the case that what I think a song will be while I'm writing it is never what it is when it's done. The hard and fast ones turn soft. And the soft ones turn dance-y and loud. Out in the world, songs just change. A similar thing happens with the videos. For instance, when we went to make the treadmill video, we actually had a different song in mind. We were going to do "A Good Idea At The Time," but walking at that tempo just felt weird. So we went back to the record and ... "Oh my God, 'Here We Go Again' is such a funny song to put to treadmills!" You know, "Ha-ha! Pun!" And that's now our most well known song. Which means, basically, videos can definitely change the cultural arc of a song.

The second answer, though, is the success of these videos full of our weirdest ideas and most homemade stuff did change the way we approached our own music. By the time we were making our third record the only thing that unquestionably worked for us has been following our own instincts and not trying to thread the needle. You know when you go back and read the things you wrote in the past, or listen to songs you wrote in the past, and you basically hate them? I can go back two records and still like our stuff and I think it is because that was the moment we started being honest with ourselves about what we actually liked and didn't like and stopped censoring ourselves based on what we thought the world wanted to hear.

STEREOGUM: You held back on certain ideas in the past?

KULASH: It's strange how you can convince yourself of things. Making our first two records, it didn't feel like we were playing anyone else's game. But I do remember writing this soft, falsetto kind of song for our second record and thinking, "Yeah, I like this -- but it's not who we are." There wasn't some label guy standing over my shoulder saying, "No." This type of thing just wasn't allowed in my own head. The totally surprise success of these videos gave us the confidence to just say, "Fuck it." We learned we should never say no to ourselves because clearly our weirdest ideas are our best ideas.

STEREOGUM: Do you ever think of doing longer videos? Is there a Phantom Of The Park or A Hard Day's Night on the horizon for OK Go?

KULASH: We don't have one in the works. Doesn't mean it's not possibly interesting. But a long form narrative film featuring us seems kind of boring to me, honestly. I could see us participating in a long form narrative feature film not about us.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]