When VNYL launched its Kickstarter campaign on December 22, 2014, the goal was to obtain $10,000 in funding. When the campaign ended 17 days later, on January 9, 2015, the project's organizers had nearly quadrupled that goal, amassing $36,000 total.

That money came in part thanks to countless news organizations who jumped on the story prior to the campaign's conclusion: Gizmodo, followed by Nerdist, Rolling Stone, AV Club, Alternative Press, Wondering Sound, Billboard, and literally dozens of others.

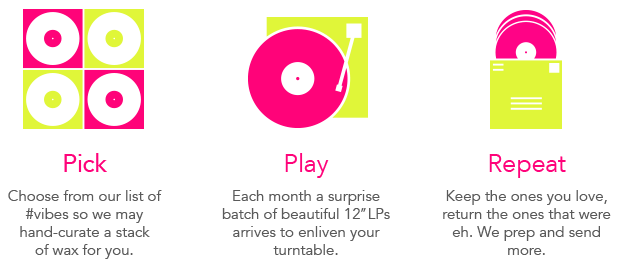

All of these stories referred to VNYL in some capacity as "Netflix for vinyl." Consequence Of Sound did a video interview with VNYL's founder, Nick Alt, who referred to his service as being like "old-school Netflix." The idea was that VNYL's staff would hand-curate a selection of three records for each subscriber (for a fee of $24 per month), and mail out those records to those subscribers, who would have no idea what musical selections they might receive. Then, subscribers would be allowed to keep those records as long as they wanted and return them at any time, at which point, VNYL's staff would send out a new batch of hand-curated records to that subscriber. Here; watch this and let Alt explain it to you himself:

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

None of these stories, however, mentioned an element of U.S. copyright law called the first-sale doctrine -- specifically section §109(b), popularly known as the Record Rental Amendment Of 1984, which makes it illegal to rent records.

The legalese may be esoteric but the message is clear:

[N]either the owner of a particular phonorecord nor any person in possession of a particular copy of a computer program (including any tape, disk, or other medium embodying such program), may, for the purposes of direct or indirect commercial advantage, dispose of, or authorize the disposal of, the possession of that phonorecord or computer program (including any tape, disk, or other medium embodying such program) by rental, lease, or lending, or by any other act or practice in the nature of rental, lease, or lending.

In short, the service being pitched by VNYL would have violated copyright law. The old-school Netflix model worked well for DVDs because movies weren't covered in the Record Rental Amendment -- but applying that same model to vinyl records (or cassettes, or CDs) would have been illegal.

VNYL was supposed to start shipping records to subscribers in early February, but it didn't actually do so till early April. When those records arrived, there were no instructions for how they might be returned -- almost as if VNYL had simply forgotten to include such instructions. Initially, this was met with cheery confusion.

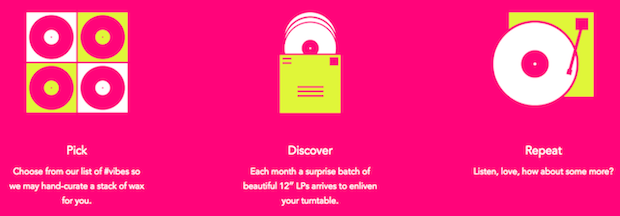

But if subscribers were "missing" anything, it was through no fault of their own. Notably (if not exactly noticeably), the service's description looked a little different on the official site than it did on the Kickstarter page. On the Kickstarter page, potential backers were told that they'd be able to "Keep the [records] you love, return the ones that were eh. We prep and send more." However, on VNYL's post-funded site, the prompt read, "Listen, love, how about some more?"

Here's how it looked on the Kickstarter:

Here's how it looks on VNYL.org -- notice too that the envelope graphic was flip-flopped with the turntable graphic; that envelope presumably made less sense when the "return" option had been erased from the "Repeat" section (coincidentally or not, the font is several point sizes smaller, too):

We reached out to Alt for this story, and this is what he had to say regarding the service's abandonment of their "Netflix-for-vinyl" model:

VNYL was Kickstarted as a "Hand Curated Music Discovery" project. I wanted to prove you could build the best human-curated music platform there is. After the campaign, I reached out to all our Kickstarter backers and asked them to fill out a questionnaire about VNYL and their own music experiences. I was really curious -- what were they listening to? What genres do they like? What don't they like? We're all being sold these digital streaming services, but VNYL is about doing something anti-algorithm and focused on how people experience and actually listen to music.

I also asked members why they backed VNYL. The vast majority (over 80%) chose to back us because they wanted to grow their vinyl collection, try a human curated service, and because they wanted to support vinyl as a medium. For a majority of our backers, the Netflix rental model just wasn't the draw and actually created the most apprehension. Since we're constantly making decisions around what the best user experience is for VNYL, it made sense to us to allow our backers and future members keep records they receive from us and pay us no additional costs.

To their credit, VNYL avoided committing any actual crime; irrespective of what they'd proposed, they never actually rented any records, they merely sold a bunch of them. Alt admits that he wasn't completely aware of the law until after the Kickstarter campaign had ended. "After the Kickstarter closed, and while we were setting up VNYL as a company, this came up," Alt tells us. However, he claims, "We could have loaned records to our backers and had them return [those records] without violating this Record Rental Exception to the first-sale doctrine." That seems unlikely; the law seems to make such exemptions only "for nonprofit purposes by a nonprofit library or nonprofit educational institution."

In any case, no one told the subscribers that the service they'd bought into was no longer "Netflix for vinyl." Yes, patrons were getting records, but they had no way to return those records. And soon thereafter, complaints started rolling in. You can find numerous such complaints on VNYL's Kickstarter comments page, but here's an example, via Rafael Macho, shared on April 21:

Hello Vnyl, how do I return the records I don't want? I can't find on your website any info ... nor there was a Netflix-like envelope with the last shipment. There is no help or contact info on your website. Seriously?

VNYL's fatal mistake, of course, was in doing a lax job of hand-curation. Had no one wanted to return the records they'd been sent, there would have been no problem. VNYL's promise was to select records for the individual subscriber based on "#vibe" -- with #vibe defined by the subscriber's existing tastes and interests -- but numerous commenters didn't feel their own #vibe had been reflected in the records mailed to them by VNYL. Here are some samples*:

Wrote Bill LaMonaca on April 22:

I am highly dissatisfied with what I was sent. All three were complete losers, and there was no real variety. And I'm not sure how you categorize the records -- I would not call Steppenwolf a "Lazy Saturday" listen, nor would I classify Uriah Heep as "Dinner Music."

Wrote Kaleena Burgess on May 8:

This was backed and bought as a birthday gift for my boyfriend who is open to all types of music. We waited and waited ... no shipment. Finally we received an email stating that our one-month trial was expiring. EXPIRING? We hadn't even received the first shipment yet. A few days later it arrived! And by "it" I mean three shitty ass old records from the '60s and '70s. Things we could have picked up in the bargain bin at our local record store.

Wrote Matt Darst on May 11:

I received three poor-quality '80s metal albums that were likely pulled from a 50-cent bin that in no way approximate my musical tastes.

Backer Vincent Chang had some positive comments to share: "Personally, I think almost every record in the world is amazing or horrible; it all depends on what we are listening for." However, the praise was tempered with requests for improved service in other areas:

[P]lease check carefully for scratches -- the one album I did like was also the one with a significant scratch on one track.

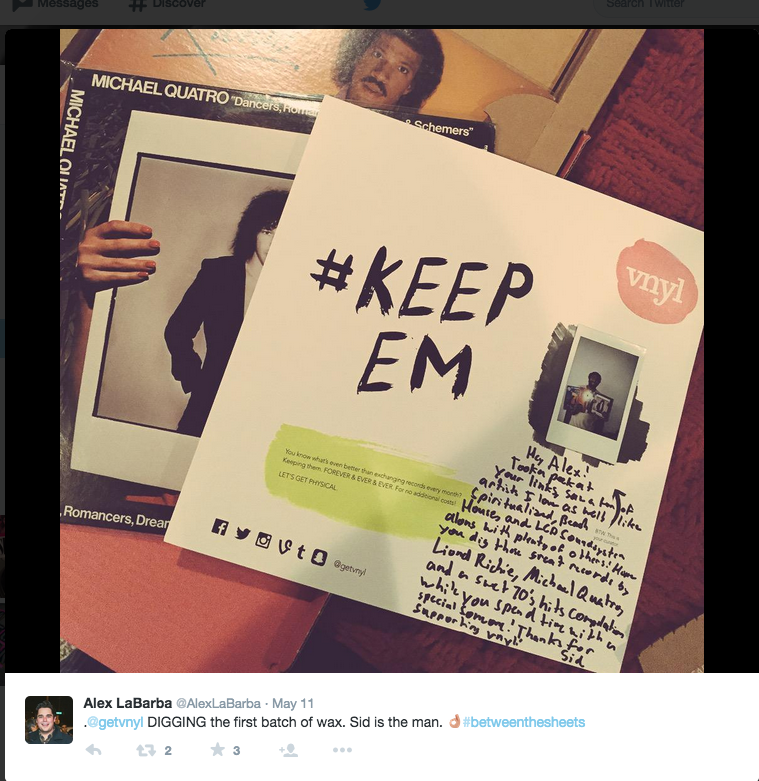

Even customers who were highly satisfied displayed evidence of hauls that seemed to fall short of what had been promised. Subscriber Alex LaBarba tweeted enthusiastically at VNYL, saying he was "DIGGING the first batch of wax" sent to him by the service. But with that tweet he included a picture of that wax, as well as the note included explaining why these particular records had been chosen for him. The note was signed by a VNYL staffer who identified himself as Sid, and in it, Sid wrote:

Took a peek at your links, saw a ton of artists I love as well, like Spiritualized, Beach House, and LCD Soundsystem, along with plenty of others! Hope you dig these great records by Lionel Richie, Michael Quatro, and a sweet '70s hits compilation while you spend time with someone special.

The "sweet '70s compilation" isn't visible in the photograph shared by LaBarba, but the Lionel Richie record is his 1982 self-titled solo debut, and the Michael Quatro record is his 1976 LP, Dancers, Romantics, Dreamers & Schemers. Both appear to be used copies with worn sleeves. (Alt admits that the majority of VNYL's current inventory consists of used goods: "It's a mix of pre-owned and new, and at the moment skews toward vintage," he tells us. "Over time, it will shift to new.") It's not at all clear why these records were hand-curated for someone whose favorite artists include Spiritualized, Beach House, and LCD Soundsystem.

VNYL subscriber Rob Baird talked to Stereogum for this story. For his #vibe, Baird told us, he chose the hashtag #lazysaturday, "based on [VNYL's] Spotify playlist, which contained artists like Iron & Wine, Jack Johnson, Sufjan Stevens, Father John Misty, and Norah Jones, who I listen to regularly and are part of my record collection." Baird also shared with us a link to his Discogs profile. This not only helps to give you, the reader, an idea what he listens to; it was ostensibly consulted by VNYL personnel in order to help hand-curate musical selections based on his #vibe. When his first VNYL shipment included old releases from Jefferson Airplane, Dan Fogelberg, and England Dan & John Ford Coley (the picture at the top of his page features the shipment sent to Baird), he took his frustration to Twitter and Yelp. He also emailed Alt directly, and shared screen shots of that exchange on Twitter. Here's a snippet of Baird's first email to Alt:

I got my first order today ... and I do not like any of the records. In fact, I do not want to keep them. I would like to return them and just get my money back. Also, please cancel my new order for May and refund that charge too. And then, cancel my account.

Concurrently, there arose a problem of perception: On April 16, VNYL opened a brick-and-mortar location in Venice Beach, CA, prompting some backers to claim they'd been victims of a bait-and-switch scam -- those subscribers believed VNYL had used a large percentage of the $36,000 of crowdfunded money not to optimize the promised "Netflix for vinyl" service, but to pay down the costs of opening a new record store.

Alt tells Stereogum that's entirely untrue:

After Kickstarter took their cut, it left us with $32,000 to spend on what the campaign said we would -- design and print amazing packaging, pay for the garage space to house all my records, and ship out all the vinyl.

The [brick-and-mortar] record store was entirely bootstrapped. When I first launched our Kickstarter, I thought VNYL would be my weekend side project ... and initially, that was all I was equipped for. Having a record store in this age of digital music is so important to me because it's a way for our customers to rediscover their love of physical music and open the doors to a whole new generation of listeners who never grew up with vinyl.

Ultimately, VNYL's representatives did themselves no favors by being so publicly opaque about the service they were providing.

"About right" indeed! Alt eventually told Kickstarter commenters to email him directly at hello@vnyl.org rather than leave public feedback on the Kickstarter page, saying, "I don't look at this comment board all that frequently, but I'm checking that email address all the time."

In fact, that was the address at which Baird contacted Alt. And Baird got a reply. In the exchange, after hearing Baird's initial complaint (excerpted above), Alt wrote:

Sorry you didn't like the records we chose for you. Do you have any more info to give as to why? Unfortunately, we don't accept returns on the records we've already sent you.

(Note the last sentence quoted there: "Unfortunately, we don't accept returns on the records we've already sent you." That obviously directly contradicts the original promise of, "Keep the [records] you love, return the ones that were eh." However, by not accepting returns, VNYL successfully circumvent any violation of the first-sale doctrine.)

Baird wasn't happy with the resolution as proposed by Alt, and said as much in a follow-up email: "I thought the whole point of VNYL was that it was the 'Netflix of vinyl records.'"

This prompted a second reply from the VNYL founder:

Sorry this wasn't what you wanted.We really do try our best on every single member, so I thought you'd like those records...

We checked out your Discogs and thought the handful we picked were ones that would be cool to have alongside your current collection. I thought for sure we nailed it for you. But I get it, sometimes we just can't seem to zero in on your tastes. Sorry about that. We obviously want you to love what you get from us ... I'm guessing there's someone else you might be friends with who might love getting vinyl from you even if these aren't quite your style.

To that, Baird replied:

If you looked at my Discogs and thought that Jefferson Airplane, Dan Fogelberg, and ENGLAND DAN AND JOHN FORD COLEY were albums I would like, you need to re-assess your business, dude, because it's not working. I'm not giving those records to anyone, I'm sending them back to you and I don't even give a shit if you give me my money back. Go pawn that shit off on someone else.

Whether VNYL could in fact "pawn that shit off on someone else" under the first-sale doctrine is a complicated matter; they'd probably be better off not trying to do so without the advisement of a lawyer. However, it remains an open question just what can be done to fairly compensate those subscribers who bought into VNYL thinking it was "Netflix for vinyl" when it would end up operating more like "Columbia House Record Club for random used/overstock albums you might find at a yard sale or storage-locker auction." Perhaps there's nothing to be done at all.

A photo posted by VNYL (@getvnyl) on

Consider this: Alt and VNYL stopped short of violating the terms of the Record Rental Amendment. Kickstarter, meanwhile, leaves due diligence in the hands of the crowd being sourced: caveat investor. Kickstarter's terms of use note that, "There may be changes or delays, and there's a chance something could happen that prevents the creator from being able to finish the project as promised." As the New York Times wrote in an April 30 story (about a Kickstarter campaign entirely unrelated to VNYL): "Although Kickstarter's terms of use stipulate that any creators unable to satisfy the terms of their agreement with their backers might be subject to legal action, no sane attorney would initiate a class-action suit on a contingency-fee basis against insolvent creators, and no sane backer would ante up the necessary legal fees." Numerous aggrieved commenters on the VNYL Kickstarter page have threatened to report the company to the Better Business Bureau, but that seems like a dead end: If it's hard to account for taste, it's almost impossible to legally enforce for taste. Was VNYL acting in bad faith, or did its curators sincerely believe those records would appeal to those particular subscribers? Here's what Alt tells us:

It fucking sucks when we disappoint our members. We honestly feel incredibly sad when a member doesn't like what we sent. That sucks for them and also for us. It's like you just spent all this time planning out what you think is an awesome surprise gift idea for someone and then they can't mask the look of disappointment when they open it up right in front of you. It's completely deflating. Unfortunately, this comes with the territory of being a human curated service.

With time, VNYL will only improve. As shitty as it feels when someone doesn't like our choices, when we do get it right, it's a total rush. There's nothing more rewarding for me or our curators when we see someone tweet or Instagram their open box of vinyl and are debating which one to spin first.

In March, Alt told the Toledo City Paper that he'd received some 10,000 requests for invites to VNYL, but was proceeding slowly in filling them -- partly because VNYL didn't have enough shipping containers to meet that demand, partly because Alt wanted to "make sure we nail it for the people who got in early." His ultimate ambition, though?

Hopefully, at the end of the day we've created something that didn't exist before in the marketplace, needs to exist, and creates new [avenues] for people to experience music in a way that they want to.

He did successfully identify "something that didn't exist before in the marketplace" -- although it didn't exist because it had been forbade by law, not because no one had ever tried to make such a thing exist. He could still, perhaps, achieve that last goal, though. The people behind VNYL could upgrade their service to eventually achieve a standard that is commensurate with their subscribers' expectations, even if it can never be "Netflix for vinyl." In the meantime, Venice Beach has a new record store -- Rick Rubin has been spotted there! If you go there, you can hand-curate some records for yourself.

//

*Per Kickstarter's regulations, only a project's backers are allowed to comment on that project's Kickstarter page. Also: All comments,correspondence, and quoted text here have been edited for style and/or grammar where appropriate.