When I saw San Francisco's revenant Faith No More play Seattle for the first time in nearly 20 years, they closed their set with "Mark Bowen," a song from their first album, named after their very first guitarist. Mark Bowen was there in the audience. It struck me as a classy move to reach back to the band's first album, one that didn't feature the band's iconic vocalist, Mike Patton. It also struck me as a dick move, since the band didn't let Bowen onstage to play his own song.

But that's the story of Faith No More: They care a lot, but they need to take the piss out of their listeners and themselves.

To many, Faith No More is a band heard but not seen. Their lone top-10 radio hit in the United States, "Epic," still receives regular play, but other than an excellent cover of "Easy" by Lionel Riche's band the Commodores, that's the sum total of their breakthrough success. It's easy to forget, however, that when "Epic" was catching fire in 1990 (almost a year after its release), Faith No More were ascendant -- one of the many West Coast rock bands that A&R reps thought might become a household name. For a minute there, it might have been them or Metallica, them or Nirvana.

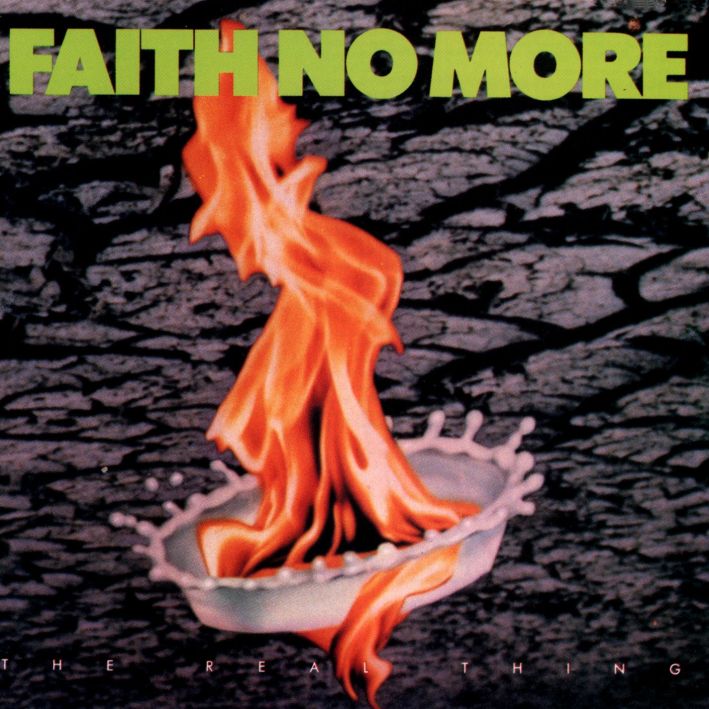

After all, Faith No More were doing as much to undermine the mainstream rock idiom of the '80s as anyone else, maybe even more so. Their lyrics, by turns emotional and perverse, frequently homoerotic, skewered West Coast machismo and then roasted it over an open flame. While MTV was trying to find a feather-haired young stud to become the perfect fusion of Eddie Van Halen and Keith Richards, Faith No More put bass, drums, and synthesizers in the spotlight, rendering the guitar sometimes perfunctory (in retrospect, maybe this is why the band changed guitarists so often). And most significantly, the band prized versatility. Jazz, funk, swing, metal, soul, new wave, hip-hop, and straightforward pop were all elements of the group's sound to varying degrees from that point on, later joined by opera, cabaret, industrial, and film soundtracks as the group evolved. Their melding of rap verses and metal guitar was not completely original (Public Enemy had been sampling Slayer and teaming up with Anthrax before "Epic" came out), but it carried cultural significance, as if announcing that hard rock music could be urban, intelligent, sexual, and cosmopolitan all at once. The amount of diversity Faith No More crammed into 1989's The Real Thing seemed to be a middle finger to arena rock, which dealt songs in two flavors: ballad and anthem.

It doesn't take much imagination to see why Faith No More are almost fully independent now. The bands that killed hair metal were trying to find something sacred still alive in rock music, but Faith No More were trying to take the air out of everyone's tires. They were chameleons, embracing irony before doing so was fashionable. Following "Epic," the band didn't so much fall out of the mainstream as swan dive.

Faith No More released three albums afterward, two of which were pretty good and one of which is a must-hear masterpiece, but never really took off, despite their adoring cult fan base. After the band's initial breakup in 1998, the group was lionized as a rock nerd's rock band. Among a certain subset of music lover, Faith No More could be used as a shorthand signifier of taste -- instant evidence that someone had taken time to dig into semi-obscure rock music.

The first reason for this is that FNM's zeal for music itself is one of their greatest strengths, as evidenced by the band's love for offbeat and faithful covers. Their recorded output includes the aforementioned "Easy," as well as Black Sabbath's "War Pigs" and, um, the theme from Midnight Cowboy. Live, the band is known for blending a few bars of contemporary radio hits into pre-existing songs. Their essential You Fat Bastards: Live At The Brixton Academy album includes snippets of "Pump Up The Jam" and "The Right Stuff," and a cursory YouTube search yields gems like Lady Gaga's "Poker Face," Portishead's "Glory Box," and Jay Z & Kanye West's "Niggas In Paris."

Whether they come from affection, disdain, or (more likely) a mix of both, none of those covers would be possible without the band's other tentpole of nerd credit, singer Mike Patton. Although not FNM's original singer, Patton is easily the most visible member of the band, both for his larger-than-life personality and his vocal skill. His six-octave range makes Patton, by one particular measure, the best singer in pop music, but he excels in other ways as well. Whereas most signers express only in terms of notes and intonation, Patton began early on to see his voice as a tool for the creation of sound, which includes singing but also the generation of noise. Owing to his background in extreme heavy metal, he's a singer and a sound-effects studio in one, not to mention a charismatic frontman. In his time away from Faith No More, Patton founded the experimental label Ipecac, and sang in less-known but still fascinating groups like Mr. Bungle, Fantomas, Tomahawk, and Lovage, each of which experimented in some way with niche music. In this way, Patton functions as a one-man gateway from rock music into esoteric and experimental music, so it's no wonder that his fan base is legion. But he's not actually the core of Faith No More's sound.

Neither is guitarist Jim Martin, who played on the group's most well known albums (after playing with Metallica's Cliff Burton in Agents Of Misfortune, in a bit of odd shared heritage). While the band's commercial hits would not sound the same without him, the band continued well enough past him, in the same way that the band existed prior to Patton.

The core of Faith No More is the trio of musicians that formed the band and who wrote the bulk of its classic material and reunion album: drummer Mike Bordin, bassist Billy Gould, and keyboardist Roddy Bottum. Each are distinct and essential in his own way. With his long dreadlocks and history of session work outside of Faith No More, Bordin is the most recognizable member of the band after Patton, and his penchant for snare cracks remains distinct, as does Gould's fierce-but-clear bass tone. Together they're a tight and inseparable rhythm section. Bottum, on the other hand, has an ear for melody, and an ability to work a hook into the various experimental tangents the band eventually took. He's historical for a second reason: as one of the first openly gay musicians in metal music (he came out in 1993, beating Judas Priest's Rob Halford by half a decade). It's tempting to regard such facts as inconsequential or incidental, but considering the recurring theme of gay sex in the band's music, it's important to recognize how critical Bottum's presence was in staking out a corner of guitar music as a safe space for celebrating gayness (even if Patton did most of the actual talking). Even without the brilliant guitarists and singers who have joined the band over the years (Courtney Love fronted briefly), the core Faith No More trio would have been a solid rock band.

With those people, however, Faith No More created probably the most well-known gateway from major label-backed radio rock into various forms of independent, nonwhite, queer, and non-English-speaking music. In other words, to a certain subsection of people they're the band that ruined wholesome rock music, and wrote some indelible tunes doing it. They were missed when they were broken up, and now that the band is active as a touring and recording entity again, it's time to recant their career up to this point with consideration and depth.

There are probably people who greatly prefer original Faith No More singer Chuck Mosley's output to Mike Patton's. Those people will probably make themselves known in the comment thread.

But I've never met any of them in person. And I'll go out on a limb and say they constitute a tiny minority of the band's fan base.

Mosley, a Bay Area punk with a mohawk, joined Faith No More shortly before independently recording the songs that would become the band's debut album, We Care A Lot. The group initially began playing with no vocalist, and invited audience members to sing for them with little to no preparation. Mosley received the position after commandeering the microphone at several "open mic" events, which raises questions as to what his competition sounded like, since Mosley's delivery is snotty, nasal, and deadpan all at once.

More charitably, Mosley is a decent lyricist and has co-writing credits on some of the album's better songs, namely "As The Worm Turns," which crept up occasionally in live sets up until the band's hiatus, and was later re-recorded with Patton.

The whole record could use a re-recording, really. Age has not been kind to We Care A Lot from a sonic standpoint. Bordin's drums and Bottum's keyboards sound louder than anything else, which is fine considering that the drums and keyboards are the strongest pieces of the music, but both betray obvious flaws: The synths sound cheap and tinny, while Bordin plays variations on a single mid-paced beat throughout most of the record. That steady groove lends the album a distinct dance-pop quality not present in the rest of their work. In 1985 people might have imagined the band evolving into a more gothic synth-pop ordeal along the lines of Depeche Mode.

The album's highlight, however, is the title track -- a ramping, bouncing number written by Gould and Bottum, and anchored in their locked-in rhythm. In a way, We Care A Lot has become a cornerstone of the band's discography; it was re-recorded for their second album, and remained a constant in the band's set list into their reunion years, long after every other song from this debut faded into relative obscurity. That said, Patton's live version of the song from the You Fat Bastards: Live At The Brixton Academy record is the definitive version, performed at a slightly sped-up tempo with a greater emphasis on the defibrillator guitar blasts that open the tune up and keep it alive. Still, one amazing song does not a great album make.

Faith No More's second record with Mosley, 1987's Introduce Yourself, is in every way its predecessor's superior, and marks the beginning of the fully formed funk-rock-metal hybrid that the band would pilot to brief mainstream success two years later. Gould's bass is far more prominent in the mix -- all the better to showcase his percussive style; Martin's guitar is a more integral (and interesting) piece of the arrangements after two years of performing with the band.

Twenty-eight years after its release, Introduce Yourself still wears its ambition on its sleeve, and at times hints toward the grand and emotive songwriting that the band would perfect soon after. For example, "The Crab Song" begins as a cheesy ballad, but thanks to some foreboding chord choices by Martin, works itself into an unsettling and groovy bit of metal that evokes both Run DMC and Judas Priest circa Sad Wings Of Destiny. It's the best cut on the record, but the Grand Guignol of "Blood" and "Spirit," the two songs that follow it, also deserve mention as hints of what's to come. And "Chinese Arithmetic" serves as the template for several of the band's singles on later records.

The title track, all minute and a half of it, is livelier than the half hour and change of We Care A Lot put together. However, the mix of punk and power-pop beneath serves as a prime example of the band's greatest weakness with Mosley: cloying immaturity. The band members literally introduce themselves, with Mosley referring to his band mates in the most emasculated forms of their names (Billy, Roddy, Jimmy), as if they're the Lost Boys, and Mosley positions himself as some sort of punk-rock Peter Pan. Worse is the non-starter storytelling in "Anne's Song" and the horrible skit that opens "Death March." No collection of music has ever been enriched by the uttering of "Fuck you I'll skate to the beach and I'll look better getting there." Not once. Which is a shame because the rest of the song achieves some drama. It's clear that for all of his shortcomings, Mosley had some insight into real darkness and had something to say about society. When he sang this superior re-recording of "We Care A Lot," there's some real anger and pathos in his voice. It's clear why he was chosen out of all the people who first auditioned to be Faith No More's singer, but too much of the time his lyrics were nonsense that his delivery failed to sell.

Apparently Mosley was as dissatisfied with the results of his work as I am. He famously fell asleep onstage during the album's release show, and was relieved of his vocal duties not long after.

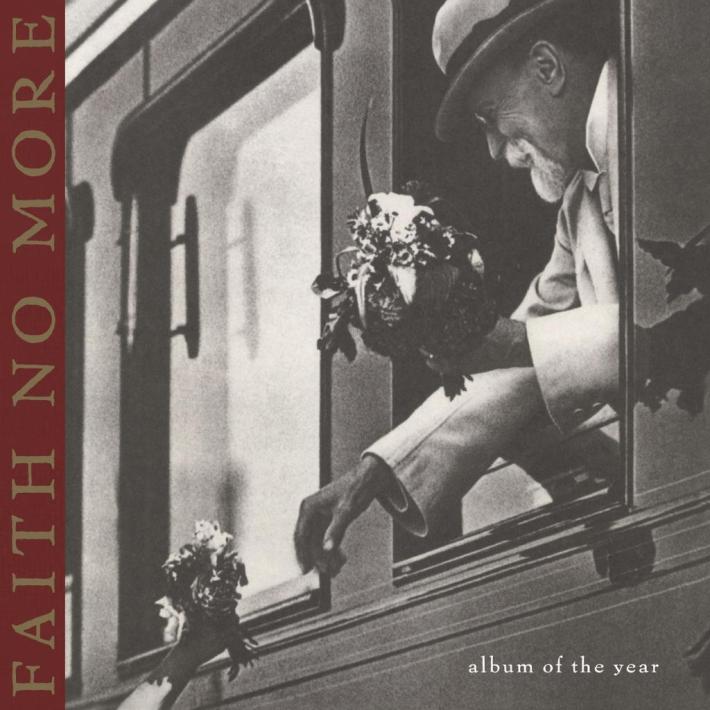

Claiming that Faith No More's work with Mosley is inferior to their work with Patton is not controversial. The esteem with which fans hold the band's work in the later '90s, however, is. While 1995's King For A Day ... Fool For A Lifetime, and its successor, 1997's Album Of The Year, have their vocal proponents, they carry the stigma of failing to live up to the expectations set by Angel Dust. Both records offered diminishing sales, and neither features guitarist Jim Martin, who feuded with the rest of the band, especially Patton, during the recording of Angel Dust. Following that album's disappointing sales, Martin was fired (reportedly via fax), leaving the band to record an album without him for the first time (Mark Bowen had left prior to We Care A Lot). To fill the void, and remembering the fighting that plagued the Angel Dust sessions, the band turned to Trey Spruance, who had worked with Patton in Mr. Bungle. Through Spruance had a history of genre experimentation, he brought out the most straightforward heavy metal elements in Faith No More -- songs like "Ricochet" and "The Gentle Art Of Making Enemies" sound at times reminiscent of Metallica's self-titled album, perhaps as an open attempt at greater radio play.

While Martin's departure fuels much of the consternation fans have with later Faith No More, it's not his absence that is felt most deeply on King For A Day. Bottum left the band for most of the recording session following the deaths of both his father and Kurt Cobain (Courtney Love and Bottum were close friends at the time). Martin had been contributing less and less to Faith No More over the years, but Bottum was a founding member and key part of the songwriting process. Without him, the band's previously madcap flirtations with other genres tapered back, resulting in their most obvious album, even with Patton screaming like a maniac, singing in Italian, and spouting gibberish. Yes, there's a dip into bossa nova on "Caralho Voador," which also showcases Patton's growing fascination with non-English-language pop music, but that song stands out in the album's lineup. The band cast a wider, more eclectic net, but did so fewer times.

To compound matters, Spruance, Bordin, and Patton were involved in a car accident early on in the recording process. Patton had been driving, and while he's been reluctant to discuss himself too personally in interviews, Patton was a known partier earlier in his career, and it's fitting that there's a song on the record called "Take This Bottle," one that's remarkably heartfelt by Patton's standards.

The result was an album that sounds somber and relatively stark, but that doesn't mean it's all straitlaced. "The Gentle Art Of Making Enemies" takes the homoerotic overtones of Angel Dust and shifts them into high gear on one of the band's most rollicking numbers. "Digging The Grave" is less humorous and zany, but still as supple as the group's best work. Things excel most with Bottum involved, as his penchant for melody brings out the best in Patton, as well as the most exotic, as evidenced on the aforementioned "Caralho Voador" and "Star A.D.," a fun flirtation with oldies.

Even when Faith No More broke from the rock formula on this album, they played it straight. For all the band's obvious love of R&B, it took them this long to write an unabashed funk-pop tune. "Evidence" is a no-frills soul jam, as well as the finest cut on the album, perhaps the result of a confidence boost pursuant to their successful cover of "Easy" and its commercial success.

King For A Day ... Fool For A Lifetime is a rough successor to a masterpiece, as well as an overly long record, but when it's at its best, it showcases a more congealed and put-together outfit than before, one less inclined to douse their songs with effects and samples. The lessons learned in making the record would pay off on its follow-up.

After an 18-year hiatus, and six years of greatest-hits-style reunion shows, Faith No More returned this year with Sol Invictus, and while it's not a jaw-dropping comeback on the lines of Alice In Chains' Black Gives Way To Blue or the Afghan Whigs' Do To The Beast, it's still a worthy piece of the band's discography, even if it takes some time to show its charm.

Recorded by the same five men that recorded Album Of The Year, Faith No More's long-awaited comeback sounds like it could have been written (though maybe not performed with such conviction) right after its predecessor, meaning those thirsting for the sublime funk metal of The Real Thing or the manic genre collage of Angel Dust are in for disappointment. Taken on its own terms, though, Sol Invictus is a polished piece of groove-heavy and soul-influenced progressive rock music, one that sports, to its credit, the finest production of any Faith No More album since 1989. It's warm, dry, and smooth, as befitting the record's title. Recorded piecemeal and at a leisurely pace in Gould's home studio (well, mostly -- Patton recorded at his own home), with minimal input from forces outside of the band, it's the most relaxed Faith No More record in terms of both tempo and attitude.

Patton pulls out a refined cast of characters from the rogues gallery that is his voice box, although he sticks in his middle and lower registers, suggesting that middle age might have shaved off some of his top octave. Still, the younger Patton might not have managed the subtle crooning of album highlight "Sunny Side Up" (one of the band's catchiest tracks, bar none) or the bellowing fire horse that is the last half of "Cone Of Shame."

Not to be outdone, the rest of the band plays it loud and, at times, surprisingly mean. Guitarist Jon Hudson is still sort of a non-entity, albeit one with a great chord vocabulary. He's still a fine second melodist behind Bottum, and the two play nicely together on "From The Dead." That said, there was a period of time where the album might have been recorded with Jim Martin, before the band decided that working with him would be too uncomfortable. As a result, while Sol Invictus is satisfying, it does carry a big old "what if?" in the guitar department. Gould and Bordin, though? They still have the low-end chemistry that was always the band's spinal column. "Superhero" and "Separation Anxiety" are some of their most burly romps together and will be fine additions to further Faith No More set lists.

The very best thing about the album is that by Faith No More standards it's pretty concise. Like many rock bands in the '90s, Faith No More hamstrung themselves by trying to fit as much material as possible onto their earlier albums, and in so doing, sacrificed consistency. At 10 songs and just under 45 minutes of music, Sol Invictus is more easily digested in one sitting. That said, there's still fat to trim. The title track and opening song is a vocal-less synth intro and, to quote a former editor of mine, the road to hell is paved with intro tracks. "Black Friday," meanwhile, is almost great but still feels somehow undercooked. Worse is "Motherfucker," a limp piece of hype work with a spoken-word vibe at the beginning -- it's probably the single worst song in Faith No More's Patton era.

In contrast, however, "Matador" is one of their best songs, channeling the operatic madness of Angel Dust's second half without any of the sonic excess. It's painting with every sonic shade the band can muster, but it paints inside the lines. To some, that defies everything that made the group great to begin with. To everyone else, Sol Invictus is a fine reunion record, but one that leaves room for a superior, more adventurous follow-up.

Complaints with Faith No More's later output fall apart at Album Of The Year. Released in 1997, the album was recorded with Gould's former roommate Jon Hudson, who proved to be a more stable addition to the team than Spruance, as well as a more melodically accomplished musician than his predecessor. His biggest songwriting contribution to the record, "Stripsearch," is actually built around a MIDI loop as opposed to a guitar riff. With Hudson on the team, as well as the core trio of Bordin, Bottum, and Gould intact from the beginning, Faith No More released a more measured and laid-back record than the band had produced previously. Hudson and Bottum in particular seem to speak the same language, and share a talent for bringing out Patton's gift for big, lovable choruses -- even though Album Of The Year is light on riffs, it sounds like a more logical continuation of the prog-pop tunes that anchor Angel Dust. For example, ebullient album highlight "Ashes To Ashes" features Patton sounding almost heartfelt, his voice seemingly trying to burst out of his body.

Put another way, Album Of The Year sounds "mature," a blasphemous term for a band of self-professed oddballs who had a reputation as crass and scatological pranksters, which may have as much to do with the band splitting as Patton's unquenchable lust for side projects. However, adulthood treated the band well. All the humor on Album Of The Year, right down to its title, feels a bit crestfallen and self-deprecating, as if the band had aged a decade since King For A Day. The sublime "Last Cup Of Sorrow" telegraphs the band's falling out while at the same time marrying Patton's Tom Waits-esque spoken growl with an instantly lovable chorus. Elsewhere, "Naked In Front Of The Computer" predicts both a quintessential piece of Internet-age angst as well as the direction that the Deftones would take their music in years later. Like too much of Faith No More's discography, it seems a bit too forward-thinking for its own good.

Though it carries the stigma of being the band's last album before their initial breakup, Album Of The Year charted well in Australia and parts of Europe. That wasn't enough to keep Faith No More together, however. A year after the album's release, and in light of Patton's growing list of side projects, not to mention Bottum's taste of surprise critical acclaim with his own side project, Imperial Teen, the band parted ways. Patton would go on to record innumerable experimental records as well as front bands like Fantomas and Tomahawk, among others. Bordin, meanwhile, became essentially the drummer-in-residence at Ozzfest, filling in for most of the crap bands that began by imitating Faith No More in the first place. Bottum scored TV and films, while Gould started his own independent label, and Hudson, um, managed real estate.

In retrospect, Album Of The Year seems lightweight, almost relieved, as if the group saw the end of their mutual run together in the distance and found with it a kind of relief. It's a great record, one that releases all the pent-up frustrations and anger from the previous two. Still, it lacks the nervous tension of their previous work, the sense that anything could happen at any moment in time.

In all honesty, plenty of Faith No More fans only listen to the band's first two records with Patton. Reasonable, considering that The Real Thing and its successor are more than good. They are transcendent.

After firing Chuck Mosley, an increasingly ambitious Faith No More began scouting for a new singer. Eventually they courted Patton after coming across the demo tape of his genre-spanning high school band, Mr. Bungle. As different as the core trio was from Martin, Patton was even further removed. At 21, he was the youngest member of the group by almost five years. And Patton was a very young 21, fond of practical jokes and clearly unsettled in his sexuality. Patton's early lyrics blister with innuendo, and interviews with him continually hovered on his fixation on masturbating and mild contempt for his young fan base (Patton became something of a sex symbol following the album's release, a role he clearly held in mixed esteem). Perhaps most alienating, Patton hailed from the small logging California hamlet of Eureka, where he spent his days roughhousing in the wilderness. The band courted him anyway, and it was the most intelligent decision they ever made.

Even if sudden immersion in cosmopolitan urban life contributed to Patton's friction with his band mates, it obviously fueled his natural showmanship and prowess. The Real Thing is his debutante ball, and he came out as a singular belle. Later, Patton would focus his career on creating unnatural and inhuman sounds with his voice, but as an exercise in pure singing, the album might be his finest moment. Albeit nasal and snotty, Patton's takes are clear and cover a remarkable range, frequently at the tip-top of his register -- and Patton rarely resorts to a falsetto. At 21, the wailing sirens that are his final big opener hits in "Underwater Love" are, to reiterate, the natural voice of someone who had never taken a singing lesson in his life.

Patton's lyrics, less mature than Mosley's though better in terms of songcraft, haven't aged overly well, but it's critical to remember that Patton penned them in two weeks after most of the album had already been written. In that tight timeframe, he wrote a pack of sex anthems that are, if not literary, at least imaginative. Where Mosley tried to critique the world around him, Patton reached into his inner psychic universe and pulled out a motley crew of characters to play-act. "Zombie Eaters" is a twee plea for affection sung apparently from the point of view of a baby, while "Edge Of The World" is its opposite: the seductive crooning of an old man (it's worth noting that this song kind of fizzles out on record, but absolutely demolishes on You Fat Bastards: Live At Brixton Academy).

But like all rock signers, Patton is nothing without a great song to sing, and the core of the band wrote a taut and cohesive set of tracks for him to breathe life into. All of the post-punk ephemera and hazy recording that clouded the Mosley records melted away, but the band's love of experimentation had yet to become a central selling point, resulting in what might dismissively be described as a straightforward funk-metal album of the sort that California was producing at the time (Primus and Psychefunkapus were active in the Bay Area, with Excel and Suicidal Tendencies spearheading the short-lived movement in Los Angeles).

Even without Patton, the album would have been a highlight of the genre. Martin, who was open with his commercial ambitions at the time, laid down the most prominent guitar parts ever to grace a Faith No More album, aiming to capture the grandiosity of his '70s guitar heroes and meld it with the slick appeal of Guns N' Roses. The song "Surprise! You're Dead!" is one of his, a holdover from his time in Agents Of Misfortune; it's one of the lone straightforward metal songs in the group's discography. Martin's interest lay more in big singles than in thrash, judging by his writing credits. Martin's name appears next to the album's three high-profile singles. His guitar solo on "Epic" is instantly recognizable, as is his work on "Falling To Pieces," and both remain perhaps the group's most well-known songs.

Running counter to that, Gould's bass work shows both power and restraint, as on the monolithic single note hits that anchor the eight-minute title track. At the same point in time, Flea and Les Claypool, Gould's obvious peers, were interested in dexterous slapping and popping -- Gould could do that, too, but he knew the value of pure sustain.

The Real Thing was a moderate success at first, receiving some positive reviews and lukewarm sales until the music video for "Epic" hit heavy rotation on MTV in 1990, more than six months after its release. The Real Thing hit the Billboard Top 200, peaking at #11 in October 1990. The song eventually became a #1 single, while the record was later certified platinum. By anyone's reckoning, even a passable follow-up record would float the band into a sustainable career. That ... didn't happen.

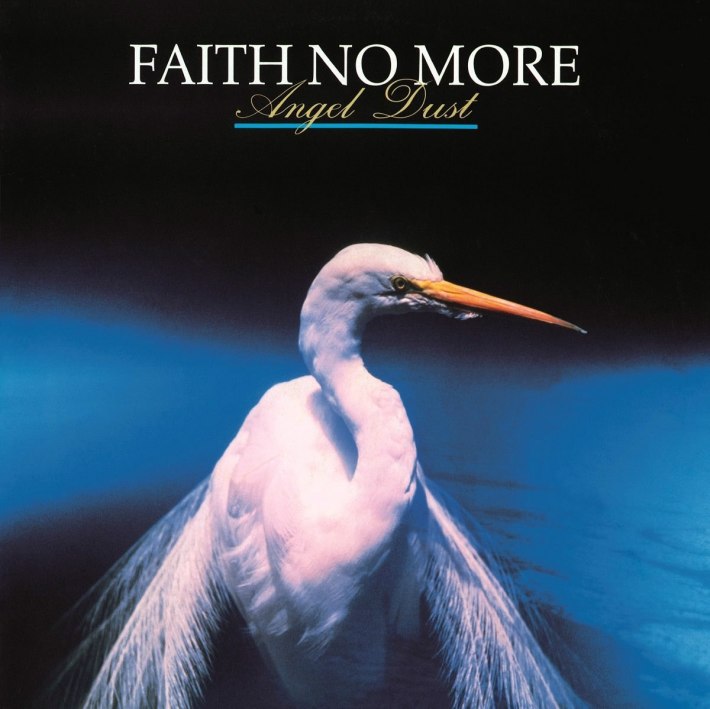

In 1990, Faith No More were essentially piloting a Boeing 747 over the rapidly changing landscape of pop music. In 1992 they decided to fly it straight into a mountain, and the brief, brilliant burst of fire and shrapnel that resulted was Angel Dust.

The success of The Real Thing had in some ways predicted the downfall of the 1980s rock idiom, as well as the stranglehold of control that the Los Angeles scene had over the country. Nirvana smashed that control completely, but Metallica proved that big, likeable heavy metal could weather the storm. Faith No More could have easily survived the sea change in heavy guitar music -- hell, they helped kick start it. What they could not survive was themselves.

In interviews from the time, the band members are sardonic, removed, and incapable of taking themselves seriously. By most accounts, the band was prone to bickering and infighting. Worse, while The Real Thing had begun to pay off the band's debts, it kept them on the road performing, wearing them down. Record industry personnel buzzed about their camp, anxious for another hit, something to give them confidence while mainstream tastes pulled a 180-degree turn. It was under those circumstances that the band retreated to San Francisco to record Angel Dust.

At the outset, Angel Dust doesn't seem so far removed from its predecessor. The production is a bit heavier and darker, with the guitars pushed back in the mix, and the bass and keys pushed forward, but that's the primary difference. The opening trio of songs are each excellent hard-rock singles. "Land Of Sunshine," bass-driven and bombastic, shows Patton in soaring pop mode as well as sarcastic social commentator, skewering Scientology and other for-profit self-help types and literally peeling with laughter. It's more dramatic and morbid than The Real Thing, but it still boasts a Martin guitar solo and instantly memorable verses. Following that, "Caffeine" pounds slower and lower, reimagining the rap verses of "Epic" as scraping spoken word. The third song, "Midlife Crisis," on the other hand, is probably the band's finest moment -- Bordin and Gould bounce like the studio floor was a trampoline while Patton constructs the entire song as a series of interlocking choruses which, at its climax, each fire at once. It rewards at least one repeat listen by design, drawing attention first to Patton's vocal prowess and then his crass humor. It's probably the most beloved song ever about a man whose girlfriend won't have sex during her period, and it remains a highlight of the band's live shows.

If Faith No More had just populated the rest of Angel Dust with songs like the first three it would have been a suitable follow up to The Real Thing, albeit one a bit too morbid to repeat its success. Rather, those songs are outliers. Four songs in, the album goes off-book with "RV," a bizarre Tom Waits-ish piano screed sung in the persona of a paranoid homebody. In one sense, it's a logical continuation of the idea that the band experimented with on "Edge Of The World," but on the other hand, it runs contrary to everything that came before it on the album as well as The Real Thing. It says "Love me if you dare."

Angel Dust is contrary on the whole. The Real Thing played with many ideas, but it presented them in a straightforward way, while Angel Dust is so heavily layered with sounds that it fatigues the ear. There may be no genre so antithetical to soul as industrial, and the band threw grating samples all over the album, particularly on Patton's first composition, "Malpractice," which seems to narrate a piece of gladiatorial combat.

Much of the album's brilliance as well as its grating bits seem to be Patton's doing. Documentary footage from the making of the album shows a band plagued with awkward silences, and Patton's tension with Martin seems nerve-wracking in particular. Martin was part of the hit-making process, as were Patton's soaring vocals, and it seems like Patton wasn't interested in either of those things anymore. As often as he sings, Patton uses his unique voice box to make sounds, to speak with the voice of monsters and perverts and barnyard animals, and then run those takes through filters, distortion pedals, and truck radios. He loved soul music but he also loved grindcore, and he employs that genre's oft-maligned "pig squeal" once or twice, but he also sings some of his finest choruses on Angel Dust. Fan-favorite "Everything's Ruined" in particular charms, even though it seems to be about the band knowingly taking their patrons' expectations and smashing them.

Patton's penchant for odd characters steers the album into territory that would never have flown with Middle America, and the lyrics make no effort to conceal or encrypt his eccentricities. The prime example is album highlight "Be Aggressive," a song Bottum wrote in order to humiliate Patton, dedicated to the virtues of male-on-male fellatio. It remains one of the band's most enduring live numbers. Patton screams "I swallow," during the pre-chorus, setting the stage for a group of cheerleaders to sing the chorus "be aggressive," tying the homoeroticism to high school sports and pubescent discovery, the most defended bastions of family values. Similarly, the last three songs on the record are "Crack Hitler," "Jizzlobber," and finally, a cover of the theme to Midnight Cowboy, an acclaimed X-rated film about a gay prostitute. In retrospect it's easy to see why the label people were flipping out. Angel Dust wasn't exactly the commercial suicide feared by Warner Bros. -- it's the band's most successful album in Europe, and sold well in re-issue, largely thanks to the bonus track, "Easy" -- but it did thumb its nose at many of the people who made the band a success.

The critical acclaim surrounding Angel Dust was immediate upon its release, and it continues. Kerrang! called it the most influential album of all time (hard rock only). What is less than immediate is the album's appeal. The Real Thing is the more cohesive, lovable record, and Angel Dust is exhausting as well as overlong. But it's also the rare rock and roll album that invites the listener to think, not just about the jagged self-combating music itself, but also about the fragmented society that produced it. It is the sound of a great band setting itself on fire rather than conforming to a capitalist agenda, even while it tries to write great arena rock music (and sometimes succeeds). Faith No More were trying to recuperate from the album and its fallout up until their dissolution six years later. In many ways it seems like it took them until this year's Sol Invictus and their reunion tour to mend entirely. It was all worth it, even if they never reach such heights again, even if everything for the band as a unit remains, in some way, ruined.