Somewhere along the way, the Black Keys sneakily became one of the weirdest bands of the 21st century. Not stylistically, of course -- and that's where a whole lot of the weirdness is rooted. There are still famous rock bands in 2015, but the topic of their decreased relevance is by now its own cliché. And then you have something like the Black Keys -- composed of singer/guitarist Dan Auerbach and drummer Patrick Carney -- who began by playing as a scuzzy blues-rock duo, garnering obvious but not always accurate comparisons to the White Stripes and existing in the more amorphous world of the early-'00s rock revival outside New York, one of the satellites off in the ether of Akron, Ohio distantly orbiting the Strokes and their ilk. That's the best you can do for these guys in terms of context. What this is really about is two men who self-recorded four rough-hewn albums with big sludgy grooves in Ohio. There might be all these quotes out there from either of them, regarding their love of rap, or just how much of a blight Nickelback is, or their rationale behind not putting a record on Spotify. All these quotes do is provide a cognitive dissonance, because otherwise the Black Keys exist almost totally removed from their time and place, making classicist rock music of the most classicist form, but never seemingly with any irony or self-consciousness on the matter. This is just the music they played. And then eventually they became one of the biggest rock bands of the 21st century.

For a band whose work is most often enjoyed best at its surface level, devoid of any larger mission or theme, there is a surprising amount of paradoxes about the Black Keys. The narrative goes now that they toiled for years for a discerning fan base and enthusiastic critics, but mainstream attention eluded them until their real breakthrough five years ago with Brothers. I mean, that's true, but it's also difficult to remember a time when, at least if you were paying attention to music publications of any sort, the Black Keys weren't a perpetual presence. They were furiously prolific -- a smattering of EPs and eight albums in the span of 12 years, not accounting for side projects and solo efforts and production gigs, which would up the number considerably. And they were always there, always getting covered, always getting really good -- even consistently great -- reviews while at the same time existing as this band it seemed easy to write off as kind of the lamest contemporary option if you were going to make a go at defending rock music's continuing merits.

It's an impressively stable buzz of critical adoration vs. a gut-punch of very shameful unhipness in admitting you actually like the Black Keys. It's straightforward rock music vs. the fact that Auerbach and Carney have, against some kind odds, found ways to develop their sound that have essentially turned them into a pop band. It's ever-increasing popularity (awards, bigger tours, even more licensing) vs. becoming an ever-increasingly easy target of derision. There are those who would celebrate the Black Keys for committing to doing this their way and making it work, for the sheer fact that you can have blues-rock licks written in the '00s echoing out over a field at 10:30 on a Saturday night during the summer. There are others that would decry them as the cheapest and most banal idol for rockists, the kind of band that would ruin it for everyone else who still cares about guitar solos.

Nothing quite makes sense about how it all happened. Nobody really gets it, even though there were those of us who watched it happen, both incrementally and suddenly. I remember days in high school when the Black Keys were new and cool. The kind of band that'd noisily and scrappily emanate from a senior's beaten up car as he exited, leather-jacketed, having recently returned to campus after leaving to smoke. (Even just recalling this scene makes me think of how it sounds like a ridiculous movie and the Black Keys kind of feel like a band born in a movie or a cartoon, but more on that in a bit). I paid attention for years, then got bored, then got hooked more than I ever had been when Brothers and El Camino came out so close together. The moment when this band became totally aggravating to people with whom I often share musical taste is the exact moment I actually started to really like them. How could a band this straightforward be a little bit divisive? Again, nothing makes sense with these guys and their career, exacerbated by the fact that there shouldn't be anything confusing about them to begin with.

As mentioned above, the Black Keys -- still somewhat shockingly -- have been around for over a decade and have produced eight records. It may require some distance before it's truly possible to divine the shifting perceptions of these guys and where their legacy stands in the music narrative of the '00s and '10s, but a fair starting point is to dig into their own legacy a bit. For the purpose of this list, we stuck with just the Black Keys' eight studio albums -- omitting the EPs, Blackroc, Dan Auerbach's solo album, etc. If there's someone out there who thinks Magic Potion is a great innovation for guitar music, make your case in the comments.

Unlike the bottom-ranked albums on some other lists of this sort, it's not that there's a whole lot wrong with Magic Potion relative to other Black Keys albums. This was their fourth album in as many years, and the last one they recorded just the two of them in a makeshift studio. Simply put: Where that novelty had served earlier records well, by now it was starting to wear thin. There could be something exhilarating about the rawness of the early Black Keys material, but these records could also grow repetitive, and their standing in the band's catalog overall is basically reliant on how memorable the hooks and riffs are, because otherwise this stuff is all pretty similar. They'd been on a pretty good streak leading up to this, but eventually the vibe had to grow stale, and this is where the band's early spark began to falter. There's solid stuff here, like the yearning "You're The One," but in the grand scheme of the band's career you could basically reduce Magic Potion to "Your Touch." It was time to start mixing things up.

Attack & Release occupies a weird place in the Black Keys' discography, a kind of demarcation between Act 1 and Act 2. The much needed change-up post-Magic Potion occurred here, through a partnership with Danger Mouse that resulted from the producer soliciting the band to write material for an Ike Turner comeback album that never came together. It was the first time the duo worked with a producer, in an actual studio. But clarity and production value weren't the issues -- the charm of those early Keys records is partially rooted in that scuzzy homemade vibe. It was more about the necessity to start varying their songs, in structure and in style, and Attack & Release is where you could first see the band making some strides in that direction. Given, everything's relative. It seems a little funny to give a band credit for experimenting when experimentation entailed adding instruments beyond guitar and drums on your fifth album. But, hey, the textures on Attack & Release were a welcome thing, whether it was the bleary 5 a.m. opener "All You Ever Wanted" or the slight psychedelia of "Remember When (Side A)."

The issue was that, while it was a step in the right direction, the album didn't have the songs on the same level as what would follow. It starts off strong. After "All You Ever Wanted" there's "I Got Mine" which at that point was a retread, but a hell of a good one. "Strange Times" remains one of the band's best songs, and probably the first time they showed us how they can craft grooves that are badass and danceable and propulsive all at once, a skill they've since employed repeatedly and seemingly effortlessly. Other than that, there's one of their finest closers in "Things Ain't Like They Used To Be," one of the earliest examples that the band could do pretty and meditative as well as thunderous, and the most promising example of the palette expanding on Attack & Release. Otherwise, though, a lot of the middle of the album drops off, and it's easy to look at moments as still just-another-Black-Keys album with some Danger Mouse bells and whistles. As a result, Attack & Release lives on mostly as a transition album -- a crucial one in the arc of their career, but not the most essential bit of listening in their catalog.

Thickfreakness came out just under a year after The Big Come Up, but the Black Keys already presented a slight but distinct modification of their sound. Even though it was recorded in similarly makeshift conditions -- supposedly in one long session in Carney's basement -- it has a more muscular and gnarly sound than its predecessor. More so than their debut, this is the album that established the template of the original Black Keys sound thoroughly and specifically, with chunkier rhythms and the blues influences moved up a few decades, to a Zeppelin-sized overhaul. In short, the album sounds like its name. While the ubiquity of Black Keys licensing is something more easily associated with their increasing fame as their career went on, it actually all started back here with "Set You Free" in a Nissan commercial. The sounds were a lot different, but between that and the developments in their style since The Big Come Up, Thickfreakness in many ways feels like the beginning of the Black Keys as we came to know them, that sometimes-inexplicably lauded and popular rock band. Thickfreakness left some Keys classics in its wake, and depending on who you ask it might remain a definitive document from the band. But, like with the other early Keys releases, repetition and the passage of time have let its initial charm dwindle somewhat. In a weird way, Thickfreakness is a kind of background mood record, the sort of thing to throw on and not really pay attention as one riff and thumping drumbeat carry on into the next. It might be the moment where they began to distinguish their personality, but it'd take a bit longer for them to distinguish their songwriting beyond an ability to line up a series of reliably blistering blues-rock riffs.

The year 2002, when the Black Keys released their debut The Big Come Up, seems like such an innocent time in hindsight. This album was a cult fixation. Who could've predicted the car commercials, the prolific licensing of this band, the festival headlining gigs, or the total impossibility of avoiding El Camino singles like, if you went outside? But there's also a kind of innocence to how this stuff was so invigorating, a grungy blues duo as a tangent to the early '00s retro rock revival business. The first four Black Keys albums were released in such a blur that they kind of, you know, blur together as entities. Revisiting The Big Come Up all these years later reveals a record that's actually quite a bit straight-bluesier than the big, chunky blues-rock riffage that'd populate its successors. Personally, I'd take The Big Come Up over some of the albums that immediately followed: I find it spritelier, less prone to the ponderousness the band could fall into during some of their heavier moments. This version of the band is now pretty much totally unrecognizable, and ironically enough there's something invigorating about The Big Come Up again in 2015, hearing the earliest and in many ways loosest Black Keys ethos once more. The thing is, that inability to now recognize this as the Black Keys puts The Big Come Up in a weird place when taking in the whole of their discography. It might be one of the better albums they've made, but it doesn't quite feel like the band we knew even by the next year on Thickfreakness, let alone now. It was an important first step and a more enduring listen than some of their other material, but also feels destined to live on as a gem of an outlier in the history of a band that would eventually choose a much different identity.

After the furious one-two of Brothers in 2010 and El Camino in 2011, the Black Keys reaching a new commercial peak, and an uncharacteristic stretch of two and a half years before Turn Blue, I remember the band's eighth album feeling disappointing. This must be anecdotal, rooted in conversations I had with people; otherwise, you have the fact that Turn Blue was their first #1 album in the U.S., another wave of very positive reviews, another lap of major festival gigs. But there definitely was something off-putting about it. These guys had learned to wield concise, rapid-fire hooks in recent years, and they followed it up with a hazy, moody foray further into psychedelia and soul? The moodiness, at least, had an explanation. While the band started sessions with the intent to produce a like-minded set of world-conquering singles after El Camino, Auerbach was going through a messy divorce characterized by unsettling allegations from both sides, which, one would imagine, doesn't make writing another batch of gloriously sleazed-out glam rock riffs all that enticing. As music, it eventually struck me as something I never really expected the Black Keys to craft -- that wonderful music critic designation known as "a grower." Sure, where everything was streamlined and crisp and going right for the jugular on El Camino, Turn Blue was murky and sprawled out in an even more indistinct way than the very-long Brothers. But over time, it's revealed itself to be a slow burn but worthy candidate for the ranks of the band's better output.

It's still best to look to the Black Keys for the simple pleasures, but adding a bit more emotional heft did them some good, too. The seven minute opener "Weight Of Love" offers Auerbach -- and the listener -- some proper guitar catharsis that burns open the path into the album. Towards "Fever," the one song that sounds like the loopy cotton-candy colors of the album's cover; towards "Bullet In The Brain" and its wondrously fried keyboard melody, the sort of thing that sounds like machinery coming undone beneath an atomic sky of some unnatural color; towards "Gotta Get Away," the sun-still-rises closer that seems to cement these guys as just a straight-up classic rock band, no longer anything revivalist. I'm beginning to feel like an apologist for what I perceive as some kind of vague schlockiness in the Black Keys' second act or in over-relying on Danger Mouse, but whatever: these guys are still getting better because they have songs now, and psychedelia is starting to look like a better look for them than blues, anyway.

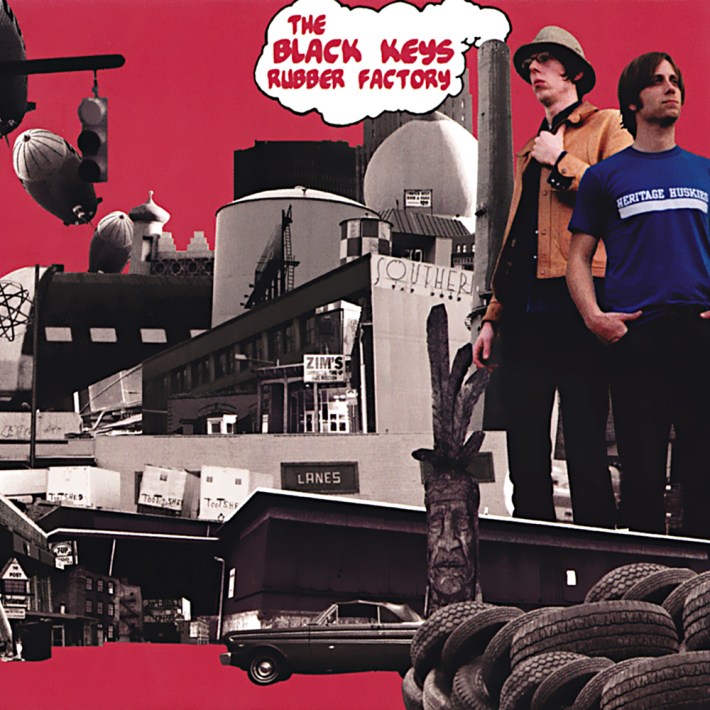

Again, the early Black Keys records live or die according to what they had to offer beyond their shared sonic territory: a more memorable riff or vocal hook, some structure or arc to the songs or album in question. Rubber Factory is easily the peak of the Black Keys' first act, a strong realization of the elements they'd built up on The Big Come Up and Thickfreakness -- so strong, in fact, that they had all their best ideas for this form here, which is why they wound up with the lukewarm Magic Potion two years later. Named for the fact that it was recorded on the second floor of an abandoned tire factory in Akron that Carney and Auerbach rented, it's also probably the peak of their initial lo-fi classic rock, the bit of their personality that'd be mythical if they were a more elusive or esoteric band. Despite the fact that it was made in much the same manner as the records that surrounded it in their catalog, Rubber Factory simply feels like more of an album. There's actual flow to this one, as opposed to a steady stampede of riffs. "When The Lights Go Out" is still amongst their better openers, a piece of ominous apocalypse blues that finally showed them mixing it up a bit with the song craft. As for quintessentially Black Keys songs, you've got "10 A.M. Automatic," "Girl Is On My Mind," and "All Hands Against His Own," which are, well, the quintessential Black Keys songs. Sometimes it's easy to group the whole of the band's first four albums together into one particular collection of music separate from the latter half, when the albums began to actually sound different from one another. The main problem there is that Rubber Factory stands starkly apart from it all, remaining one of their best releases.

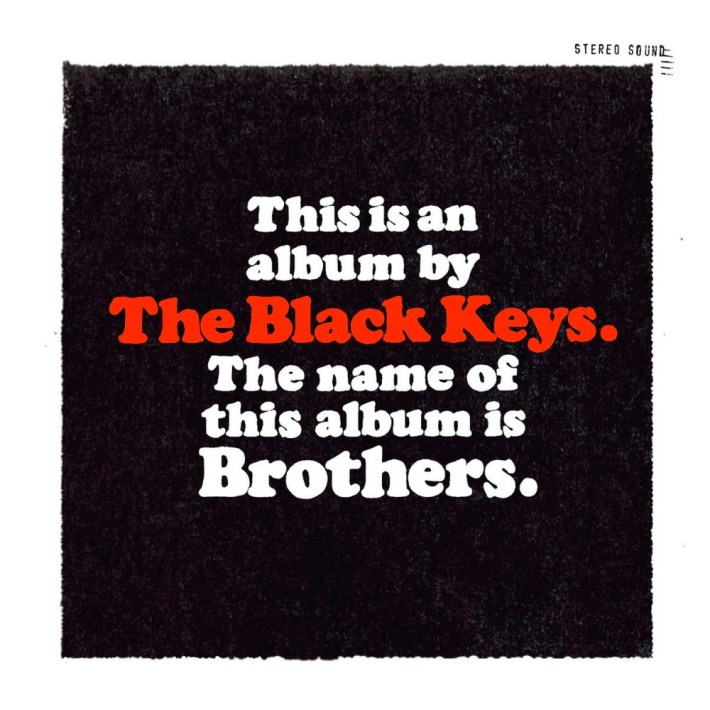

Over night but also after five albums, the Black Keys changed. Attack & Release might've hinted at some new diversity in sound and style, but there were still stretches of that record that sounded rooted in the Black Keys' earlier work, just dressed up with Danger Mouse's influence. I remember having moved on from Black Keys before Brothers came out. They were the kind of band I liked throwing on when I was younger, but it had all started to get too boring, too similar. And then Brothers came out and floored me, and a lot of other people, too. It might've been easy to find Black Keys on festival lineups and in commercials and TV shows before this, but this was different. This is one of those weird things about this band's career: they got steadily positive reviews and constant licensing deals, but somehow Brothers felt like a turning point where they really blew up in a more mainstream way, partially rooted in the fact that "Tighten Up" and "Howlin' For You" felt ubiquitous regardless of their chart positions (which were the highest the Black Keys had yet achieved, anyway).

From a musical standpoint, it felt like the band finally arrived someplace that was both surprising for them and had, in another way, been awaited for the preceding several years. Soul and psychedelia and straight classic rock influences fleshed out their sound; Auerbach employed a falsetto surprisingly well on highlights like "Everlasting Light," and "The Only One." "Next Girl" might be the last old-school Black Keys song the band has done, and it's one of their best in that form -- its familiar chug possessing more urgency than usual. In different ways, "The Only One" and "Sinister Kid" had addictive grooves that set the stage for the across-the-board infectiousness of El Camino. Most importantly, though, Brothers was perhaps the first Black Keys album that felt like it had a reason to exist relative to their other work beyond the fact that some time had passed and it was time for them to crank out more music. Auerbach and Carney had reached a breaking point leading up to this album. Between Carney's divorce and Auerbach's solo album Keep It Hid, which Carney claims was a complete surprise to him, there was the possibility that the Black Keys were done. But they reconciled and made an album called Brothers. It felt like a mission statement, finally, for what the Black Keys could be beyond the one trick they'd learned to do really well in the first phase of their career. Its unruly swampiness is part of what makes it great, but might be too much to make it their masterwork. But it's also likely that, depending on how many more records these guys release, it will live on as perhaps their most definitive work: The one where it really felt like they had a stake in it this time. And it paid off, resulting in an album that summed up everything these two did well together.

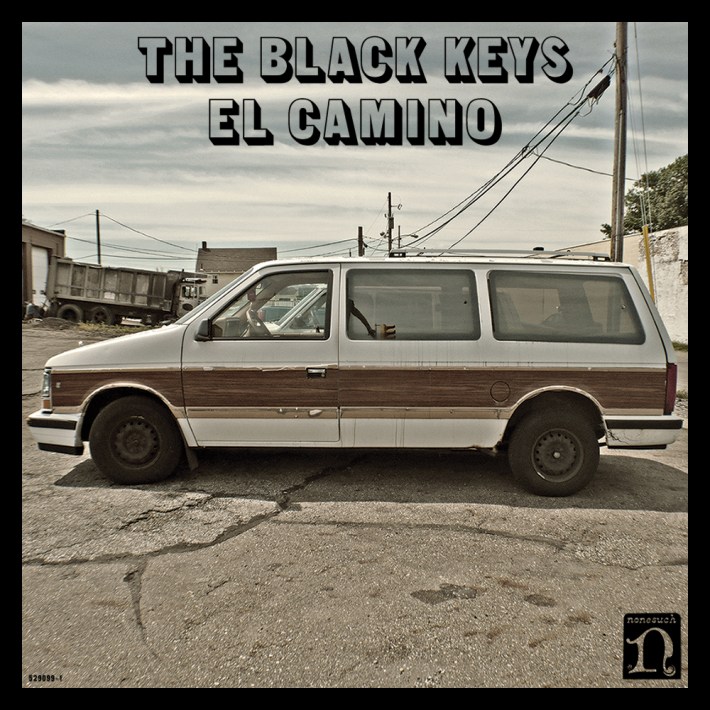

There were popular singles and accolades and Grammys for Brothers. It was the band's breakthrough, but in many ways it still feels like the setup for El Camino, the album that snuck up the following year and really catapulted these guys into the kind of rock stardom that isn't supposed to exist anymore. It's been three and a half years since El Camino came out, and in that time I can't remember any letup in the persistence with which I hear "Lonely Boy" and "Gold On The Ceiling" and even "Dead And Gone" and "Little Black Submarines" (the other two, slightly-less-ubiquitous singles) constantly. I don't even know where and how and when, they’re just the kinds of songs that have perpetually felt inextricably a part of the atmosphere since they were introduced to it. Given, the Black Keys achieving this kind of popularity isn't necessarily what makes El Camino their best album. I know plenty of people who were into this band and can't stand their recent iteration; I know people who hate hearing these songs again even as, somehow, they haven't lost any of their impact for me despite their extreme overexposure.

There's a kind of cartoonish rock ideal you could pin on the Black Keys, a reason to not take them seriously, I guess. That's most evident in the psychedelic trappings of Turn Blue or the big glam-rock riffs of El Camino, but, you know what? This band was always a little cartoonish, it's just that they had that cultish, lo-fi vibe to hide behind for a few records. The Black Keys have become better for embracing all the baser pleasures of rock music: this is a brisk album full of your stock rock tropes of cars and women and all that. It isn't profound, and that's kind of why it's great. This is one of the most shameless, sleaziest, glitziest big rock albums in recent memory, made all the better for the fact that there isn't a drop of irony in the Black Keys' being. They actually have the out-of-time rock star status that backs this stuff up.

Not that it needs a whole lot of support, necessarily. The other way El Camino distinguishes itself from almost every other Black Keys release is that there is no filler, no wasted space, no meandering. These are eleven relentless tracks, written with the live setting in mind. (Presumably a packed festival crowd, where these songs do indeed flourish.) These are songs labored over with the specific intent that the hooks and riffs and little instrumental touches are as economic and deliberate as possible. Whether it's the singles, or the way "Money Maker" and "Run Right Back" seem distantly reminiscent of early Keys material only hammered into far more memorable form, or the way the weird synth sound at the beginning of "Nova Baby" and the '70s coke-rock riff of "Mind Eraser" are equally as catchy, El Camino doesn't mess around. Auerbach admitted the lyrics -- written after the songs were completed -- are meaningless; the album title is a joke. Really, though, were the Black Keys ever a very meaningful band? This is the moment they embrace that totally, crafting a rock album that is made for mainlining endorphins. It's not the sort of album you want a bunch of other bands to start making, but when you have someone like the Black Keys find the sweet spot in their talent and it results in something that's as much of a mindless, mind-numbing good time as El Camino, it's impossible to resist.