In season four of Dawson's Creek, there's an episode, called "Great Xpectations," where Dawson and his gang of photogenic friends go to a rave. Plotwise, it's about what you'd expect from a Dawson's Creek rave episode: They have follow a "yellow brick road" to the party, the music is somehow not loud enough to drown out long-winded romantic squabbles, one girl overdoses on ecstasy and almost dies. And the music is also exactly what you'd expect to hear on a Dawson's Creek rave episode, which is to say that it's made up entirely of Chemical Brothers tracks that were years old at that point. For something like five years, the Chemical Brothers were put in the unenviable position of demonstrating, for a vast and clueless American public, what this rave stuff was all about. Labels and press were hyping the coming wave of electronica, but nobody quite knew what that meant. This music had been underground in America for years -- it had been created as underground American dance music -- but after seeing the way it could move thousands of kids at European outdoor festivals, various monied interests were hoping to turn it into the next white American youth-culture wave once grunge died out. And it did become a dominant white American youth-culture wave; all it took was many years of club-culture development and the cultural influence of Jersey Shore. The Chemical Brothers are headlining dance-music festivals in America still, but the strains of festival EDM that have blown up the hugest have nothing to do with the music they were making once upon a time. Still, they made an impact in America and around the world, and they did it without resorting to attention-grabbing goofiness. The late-'90s dance records that had the biggest popular impact in the U.S. -- the Prodigy's The Fat Of The Land, Fatboy Slim's You've Come A Long Way, Baby -- today sound as fun-but-gimmicky as any of the popular ska-punk albums that were coming out at the same time. The Chemical Brothers found a more difficult way to break through: They made two of the best psychedelic rock records of the '90s. The first of those, Exit Planet Dust, had its UK release 20 years ago today.

I remember my teenage self being deeply flummoxed when critics would talk about how the Chemical Brothers made a form of dance music that rock listeners could get behind. To my rock-reared ears, this stuff sounded weird as fuck. Only two of the songs had any kind of singers, and the duo mostly didn't even use the repeating-vocal-phrase sample technique that I'd already gotten used to, thanks to Baltimore club and the rare late-night moments when I'd hear Moby or the Prodigy on the radio. Instead, these were two nondescript weedy-looking guys making entirely-instrumental music, music that was just drum sounds with weird noises piled up over them. And because the album sequenced these tracks to flow into each other, it was just about impossible to figure out when one song ended and another song began. When I put it on his car tape deck, a friend sniped, "When is this song going to end?" before ejecting the tape and throwing it out the car window. (He promptly apologized, and we spent about 15 minutes looking for the cassette in the grass outside. A couple of years later, when he did the same thing with Madonna's Ray Of Light, he broke the tape, and I got royally pissed.)

I had to radically recalibrate the way I listened to music to make any kind of sense out of the thing. But I kept listening to it, and it paid off. I forgot about deciding which song was my favorite and which one I'd put on a mixtape, and I got into the flow of the thing instead. Actual songs stopped mattering to me, and the things that stuck with me were the moments, like the part on "Chico's Groove" where one bassline gives way to another, or way the beat dissolves miasmically and then snaps violently back into place on "In Dust We Trust." Something about the album had to keep drawing me back, to intrigue me just enough that I'd stop listening to Reel Big Fish for an hour at a time.

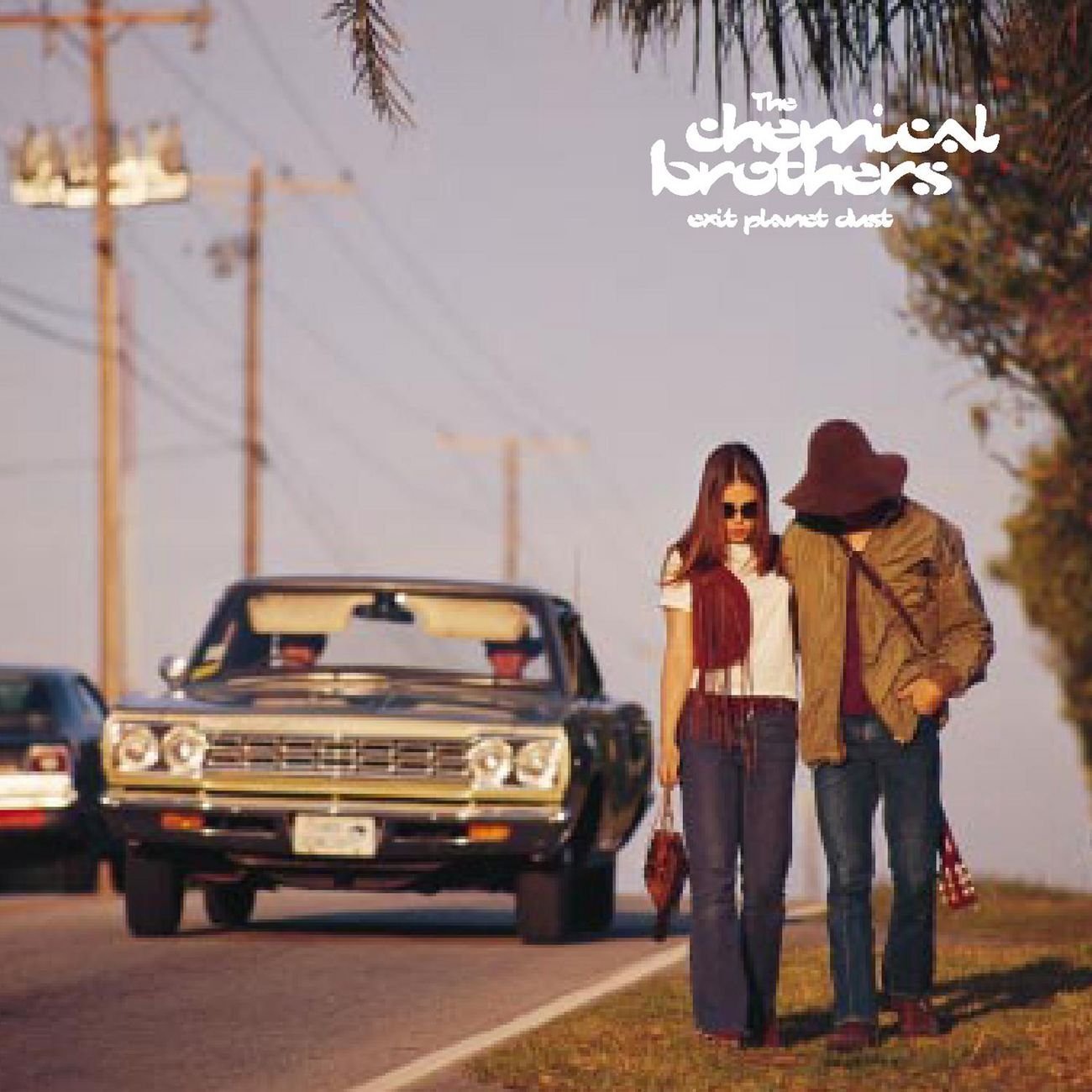

Listening to it years later, it's a whole lot easier to understand what those critics were writing about back then. Exit Planet Dust is a psychedelic rock record, the big instrumental rave-up that, say, the 13th Floor Elevators might've made if they'd had access to mid-'90s technology and less-damaging drugs. The drums aren't nimble house drums; they're big, gallumphing thunder-bombs, even approaching Bonham territory on "Playground For A Wedgeless Firm." The bass-tones aren't computerized rumbles; they sound like someone ran John Entwistle's axe through a whole pile of fuzz pedals. the synths don't needle or stab; they riff. There's a reason why, in an age of producers using non-representational CGI polygons for their cover art, the Chemical Brothers went with an image straight out of Dazed & Confused.

They weren't making a record for DJs, though a few of the tracks on Exit Planet Dust apparently did get major club play. They were making an album of fired-up stoner music, one that was intended to be received as an album. Album-oriented dance music was a pretty new thing in the mid-'90s; techno was a singles genre. But Exit Planet Dust was a landmark in figuring out how this stuff could play in album form. The structure -- bangers up front, woozy pretty music on the second half -- pretty much defined the way most people would assemble dance albums for at least the next few years. And maybe that's why Exit Planet Dust has aged so much better than so many of the albums that came in its wake. There's no forced crossover, no pay-attention-to-me gimmick. Instead, it maintains and manipulates a mood, and it does it without dissipating into ambience. And on the two tracks that do feature vocals, those vocals serve a purpose. On "Life Is Sweet," Charlatans UK frontman Tim Burgess taps into a lost-little-kid stumble that unites the Chems with the Charlatans' Madchester scene and, by extension, the jangled-up '60s music that inspired the Madchester scene. And on album closer "Alive Alone," previously-unknown singer-songwriter Beth Orton coos over sitar samples and accesses the starry-eyed longing that Orton was never able to conjure on her own. To this day, I'm mad that we never got a full album of Chems/Beth Orton collabs. They sounded better together than either ever sounded on their own.

Exit Planet Dust was a culturally important album, and an influential one, at least for a while. The combination of rave sirens and psych-rock far-outness was probably what convinced people like Noel Gallagher and Mercury Rev to jump onboard when the Chems made their even-better follow-up album Dig Your Own Hole two years later. And in the second half of the '90s, spaced-out dance music came to rival Britpop as the dominant sound of young people getting fucked up in the UK, as you'll hear on the Trainspotting soundtrack. Exit Planet Dust was a big part of that. But if you look at the dance music that's taken over the world in the past few years, the bleary space-rock force of Exit Planet Dust is basically a nonfactor. These days, it feels like the Chemical Brothers most influential song is their shallow 2005 Q-Tip collab "Push The Button." Songs like that are what led American executives to realize that dance music could make ideal beer-commercial soundtrack music, and I'd argue that that's what really led to the EDM takeover. I'm not even mad at the way festival EDM has taken over. I get it. Watching Kaskade draw the biggest crowd of anyone at this year's Coachella was an instructive experience; why shouldn't these vast throngs of kids dumb out to sugary melodies and cinematic buildups? It's a formula, but it's one that works. Still, it's nothing compared to what this music can be. Five years ago, I saw the Chemical Brothers headline a rock festival in Sweden, and it was probably one of the five best festival sets I've ever seen. In a crowd of Europeans, in a place where this music has moved crowds like that for decades, I felt an echo of the dizzy communal transcendence that was always supposed to be the point of this music, something I didn't get from Kaskade. The Chems worked a couple of Exit Planet Dust tracks into that Swedish festival set, and they felt right at home.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]