Like almost everything else about it, the release date of Sufjan Stevens' Illinois is almost too perfect. It's one thing to write an album about what it means to want to believe in your country during a time when many people struggled to believe in anything. It was something else to release that album on the Fourth of July, America's birthday. But it's not like Stevens has ever had much of a problem with gilding the lily.

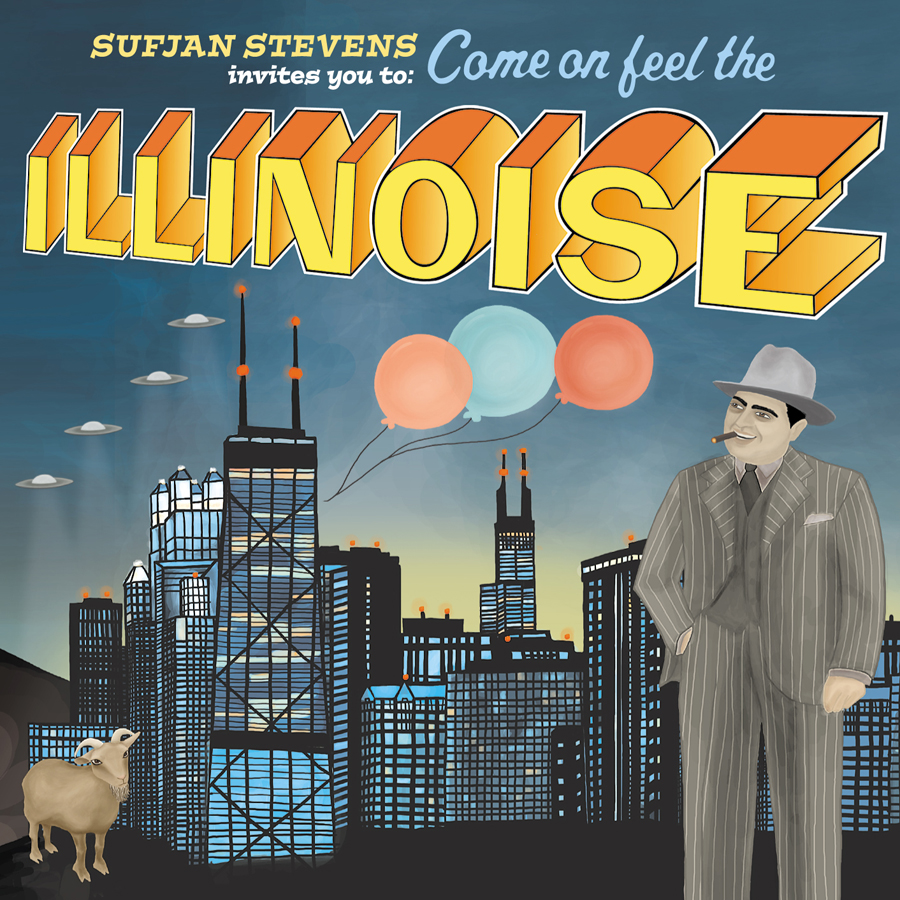

Illinois (or Sufjan Stevens Invites You To: Come On Feel The Illinoise, if you simply must) was billed as a musical tribute to the grandeur of our 21st state, and yeah, it is that (Stevens famously researched the hell out of the state before recording; going on road trips, getting stories from the locals, and even looking up immigration records), but that's ultimately just a feint. Really, Illinois is an album about America, and all of the myths, quiet heartbreaks, and indefatigable hopes a country can hold. And it turns 10 years old this weekend.

When looking back on Illinois, it's worth keeping in mind two things about the time when the album was released, and if you don't like it when entertainment publications get political, you may as well just skip this paragraph. The first is that in the wake of the success of the Arcade Fire, Bright Eyes, and, uh, Clap Your Hands Say Yeah, there was a feeling in the air that the traditional paths to popularity were breaking down, and all an artist needed to conquer the world was talent and the support of the right blogs. It didn't really work out that way in the long run, but it was an exciting moment, and every breathless Rolling Stone review and NPR profile indicated that the entire world was Sufjan's for the taking if he wanted it. But more crucially, in the summer of 2005, young, left-leaning creative types -- i.e., Stevens' target demo -- were still reeling from the re-election of George W. Bush. This was really what America wanted? It was a nasty time. Both sides dug their heels in throughout the year, ever more determined to have as little to do with the opposing team as possible.

And into this fray marched a skinny, effete Brooklyn hipster with a bunch of songs about the all-forgiving grace of the Great I Am and what a magical and weird place the Midwest is. Stevens, aware of this strife ("The Tallest Man, The Broadest Shoulders" might be about a frontier battle, but don't think the line "What have we become America?" got there by accident) wanted us to see that God and country was for everyone, not just Them. And the godless blue state kids went nuts for it. Only in America!

I kid somewhat, but in era when irony was the default pose of the cool, and caring about things left you open to attack, Stevens' sincerity felt heroic. We needed some damn catharsis. Of course, one of the reasons people like irony is that sincerity gets cloying if that's all that's being offered. Fortunately, Stevens also had songs. Good lord did he have songs.

Illinois is entirely too long, way too much and still just absolutely perfect. Stevens was on such a roll here that even the funky song about zombies worked. Until I began re-listening to the album in earnest for this piece, I hadn't heard the last song "Out Of Egypt, Into The Great Laugh Of Mankind, And I Shake The Dirt From My Sandals As I Run" in years, and now I wonder why I deprived myself. Of course, it could have been even longer. The Avalanche: Outtakes And Extras From The Illinois Album was released the following year, and it makes the argument that this could have been a great double album, except that for once Stevens didn't feel like showing off.

By the middle of the decade, the "Return of Rock" vogue was starting to wane, and artists were looking into other areas besides distorted guitar for inspiration. In Stevens' case, that meant tapping into the chamber-pop template that Belle & Sebastian had established, as well as modernist composers such as Steve Reich and Igor Stravinsky. There are odd time-signatures, literal bells and whistles, wave after wave of overdubbed strings and choir vocals, banjo upon banjo, and all matter of quirky sonic beauty. The sheer sound of the thing is impressive, especially considering that Stevens recorded a lot of it on his own. But listening to the album now, what strikes me are the words. Stevens moved from Detroit to New York City to study writing at the New School For Social Research, and Illinois is as fine a short story collection as you could hope for.

While he's one to Go For It musically, at least here, as a writer Stevens tends to give just enough information to fill in an entire world. We're not quite certain what happens on "The Predatory Wasp Of The Palisades Is Out to Get Us!", but we learn all we need to know about sexual awakenings, regret, and spending your life wondering if you moved too fast, or too slow. On "John Wayne Gacy, Jr." a few lines about what lurked under the floorboards turned the notorious serial killer into almost an elemental evil (do you remember the first time you heard Stevens sing "oh my goooooddddddd?" Of course you do), a stand-in for the darkness at the core of all men and this country, a darkness that we must stand vigilant against. My friend and colleague Rob Harvilla once said that even just thinking about "Casimir Pulaski Day" was enough to make him cry, and that's actually the only reasonable response to this delicately wrought story of the death of a childhood friend and perhaps the death of faith itself, complete with the saddest horn part since Nate Walcott helped Conor Oberst mourn America a few months previous on "Land Locked Blues." There's also a line about a cardinal that I can't write out for fear that I'll just lose it.

And then there is "Chicago." Oh, how there is "Chicago."

"Chicago" is easily one of the five best songs of this century and the song Stevens is best known for (partially due to its inclusion on Little Miss Sunshine). A road trip song par excellence about what seems to be an especially harrowing journey from Chicago to New York to adulthood, "Chicago" finds an entire army of backing vocalists and horns administering CPR to the last vestiges of the protagonist's innocence, before they must accept the fact that things will never be the same again. But it's too late. Too many mistakes have been made, too much has been said, and they'll never be able to go where they were before the trip began. We don't know what happened, and we don't need to know. It's not our business. We just know they'll never be able to go back to Chicago. But at least they'll have a good cry about it. (Stevens, or at least Stevens' characters, admit to crying all the time on this album, because Stevens has no use for your suffocating masculine archetypes.) Listening to this album 10 years on -- and this is corny but whatever -- I hope the character realizes his traveling companions aren't mad anymore, and probably weren't as mad as he was making them out to be. We all make mistakes.

Illinois was rapturously received, but the backlash was almost immediate, which is as it should be. When it comes to an artist of substance, a backlash is nothing to worry about. It proves that you're taking enough risks to piss people off, and you have the courage to commit to your affectations. Only cowards go halfway, out of fear of riling the commentators. And besides, complaints that Stevens is too delicate or twee is basically coded homophobia and misogyny from those who don't like their traditional notions of masculinity toyed with in any way.

Part of the mythology of this album, which I'm addressing here toward the end because I feel it's too prominent in the story of Illinois but I can't ignore it and remain truthful, is that it was the second installment of a plan to write about the history of all 50 states. Look, artists spend a lot of time giving interviews, and sometimes they get bored, or they worry they're coming off as boring, and they say outlandish things. It happens. We shouldn't hold them to it for the rest of their careers; he later told The Guardian that "I have no qualms about admitting it was a promotional gimmick."

After Illinois, it seemed like everything was on the table for Stevens. All he had to do was make an album that tightened up and refined his sound a bit, name it Missouri, maybe write a tearjerker based around a St. Louis riverboat casino, and he would know the glory of a Coachella headliner's vegetable tray in perpetuity. Instead, he retreated. Perhaps the attention was too much for him. Perhaps he didn't want to repeat himself or be turned into a caricature. Instead, he wrote a symphony about the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, and then made an elaborate electro-pop album and went on a tour that featured choreographed dancing inspired by Janet Jackson. (Always a smart guy, Stevens jumped on the poptimism train way ahead of schedule.) Earlier this year, Stevens released Carrie & Lowell, an album that put away all of his rhetorical and arrangement skill to simply tell the hard, honest truth about the mother he never knew. If you get tired this weekend and want the damn cookout to end already, throw on "Fourth Of July" and your guests won't be able to slink out fast enough.

Stevens is a clever guy. "Decatur, Or, Round Of Applause For Your Stepmother!" is a series of ingenious rhymes and historical references that feel like a McSweeney's submission put to jaunty folk-rock, and there are several other times on Illinois where Stevens goes right up the line of too arch, too maudlin, too much. But he always pulls back.

You can never really tell with him, but I like to think that Stevens is aware that someone with his level of talent can easily get lost in craft for craft's sake, or come to believe that dazzling us with his skill is an end in and of itself, and that he must be on guard. On the title track, the third to appear on the album after a few preambles, a backing chorus asks, "Are you writing from the heart?" It's a good question for any artist to ask themselves. The rest of Illinois was his reply.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]