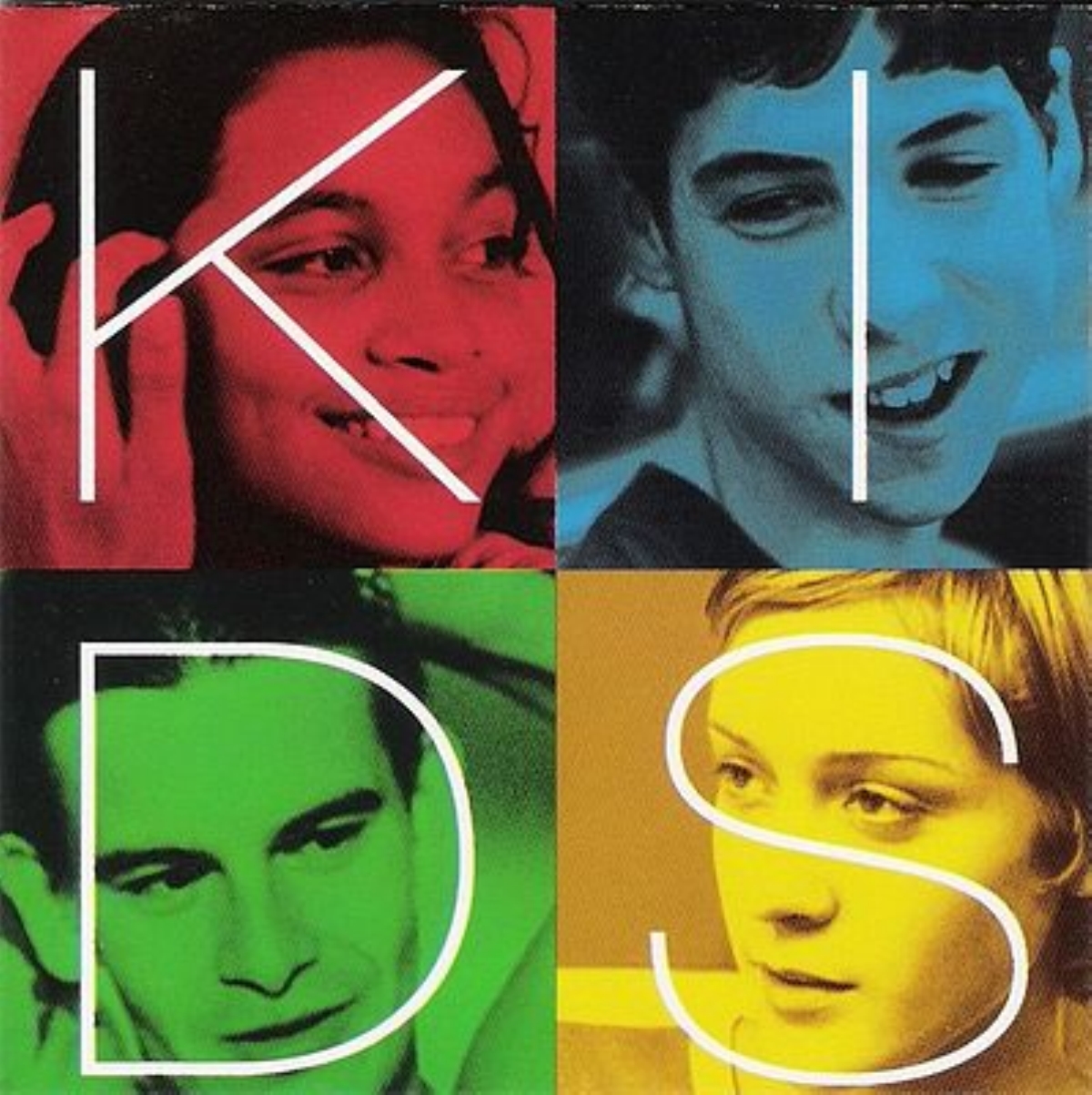

This week marks the 20th anniversary of Kids -- Larry's Clark's infamous, lascivious, inflammatory film about a bunch of New York City teenagers drinking, drugging, fighting, skating and, most notoriously, having sex with virgins. Given how commonplace such subject matter has become in recent years, it's easy to forget just how controversial Kids was at the time of its release. Janet Maslin famously referred to the NC-17-rated film as a "wake-up call to the modern world" in The New York Times, and many critics found the movie's quasi-documentary style and unflinching depictions of rape and sex among minors (the movie famously opens with the seduction of a 12-year-old girl) to be something akin to child pornography. Regardless what you thought of Kids, there is no denying that the movie was more than just a lightning rod for controversy (I myself nearly got booted from my small Oklahoma college for staging an unauthorized screening of the movie on campus): It opened up a dialogue about just how far a mainstream movie could go in its depictions of sex and violence. It also provided a window, albeit a profoundly fucked-up one, on how some urban teenagers actually lived and talked and related to each other. The movie's perceived ambivalence regarding violence and female victimization -- not to mention it's grim, questionably moralistic HIV narrative -- inspired a million think pieces and grad school film dissertations. The movie itself, while by no means a fun watch, is a fascinating look at '90s youth culture. Aside from essentially launching the careers of Harmony Korine, Chloë Sevigny, and Rosario Dawson, the film also generated what would become one of the most ubiquitous and era-defining movie soundtracks of the 1990s.

Curated and compiled by Lou Barlow, the Kids soundtrack featured music from almost all of Barlow's various projects -- Sebadoh, Folk Implosion, Deluxx Folk Implosion -- as well as perfectly chosen tracks by Slint and Daniel Johnston, among others. For those of us having the indie-rock college experience in 1995, the Kids soundtrack was, at least for the better part of a year or so, basically the soundtrack to our lives. For lots of folks, the soundtrack provided a crucial first contact with Johnston and Slint (I knew more than a few people that went out and bought Spiderland after Kids), and the number of times "Natural One" or "Nothing Gonna Stop" provided the background to blackout-inducing house parties or lengthy weed-smoking sessions in my dorm room is basically incalculable. Even now, two decades later, the Kids soundtrack still sounds great. I may truly never need to watch the movie again (or buy any of the Larry Clark-approved swag produced by Supreme to commemorate the occasion), but I'll never get tired of listening to Sebadoh's "Spoiled" and shudder at being reminded of just how scary and beautiful and often deeply tragic it sometimes is to be a teenager. Or a college student. Or an adult, for that matter.

Barlow has a new album coming this fall, which you'll be hearing about soon. In the meantime I talked to him about Kids and how the soundtrack came to be.

STEREOGUM: How did you come to be involved with Kids?

BARLOW: Harmony Korine, the screenwriter, was really into my early work. I did a lot of stuff under the name Sentridoh and a lot of 4-track cassette stuff that he was into. He started writing me these long letters pretty early on. My girlfriend at the time, who became my first wife, eventually wrote him back. We didn't think too much about it. We were getting these really intense letters from this kid. Then it turned out that he actually sent me his screenplays. He sent me one for Kids and then one for something called Ken Park. I read through the screenplays and I was like, "That's pretty stark." Then, pretty soon [afterward], he was really doing a movie, and he was doing it with Larry Clark, and he wanted me to come to New York. He wanted me to do the soundtrack, to score it. He wanted to use certain pieces of mine from my early cassettes in the movie. He was really excited and he wanted me to come to New York and meet with him and Larry [Clark]. That's when I realized it was a real thing. It was a big deal.

STEREOGUM: Had they already shot the movie by that point?

BARLOW: No. It was kind of cool because they involved me in the very beginning of the process. I actually saw them casting it.

STEREOGUM: Wow.

BARLOW: The cool thing about them was they really wanted to do it from a very artistic point of view and in a very organic way. They wanted me to be down there because they liked the idea that theoretically I was this sort of East Coast nerd guy living in my sheltered academic Boston community -- which isn't entirely true -- but that was their perception of me. They liked that I would come in and write something inspired by what was happening in New York. They thought it would be an interesting juxtaposition, which I thought was perfectly reasonable and kind of an interesting way to approach it. I enlisted my partner John Davis, whom I was doing the Folk Implosion with at that time. We were just in a really good spot as writers and friends and collaborators. I got John involved because he and I just talked all the time. We were always talking and brainstorming about musical ideas. I thought he would be the perfect person to help me with it. So that's what we did.

STEREOGUM: That is pretty amazing. I've done a tiny bit of music supervision and I know how the process often works. You don't always get to be involved with the aesthetic of the project from the ground up.

BARLOW: No. I think as we went along in the process and as the movie was being shot, we started really working on the score. You'd have to go to the screenings with all the people involved, and that's when I got a taste of the bullshit involved. Some studio guys would be like, "There's a Latino girl leaning out a window. There should be salsa music playing!" Such fucking idiots. We'd be like, really? To be honest, we experienced very little of that stuff. In the end, we had so much of our real organic and very inspired-by-the-film music in the film. We were able to do it in a pretty raw way. We did it on a 4-track -- a lot of it, anyway. Then, at the end, when everything was actually all done and scored, they were like, "There's one little piece we'd like you to finish. Why don't you go in and finish that and put some vocals on it, so we can have a song for the movie?" It was awesome. The guy who was the actual music supervisor for the film is very successful and he's still doing it. His name is Randall Poster and he's very good. He was actually a really encouraging presence in the midst of all this. He was very close to Harmony. He would come up to Boston and talk to me and John, and he was very nice and very supportive. He just gave me basically free studio time to do whatever I wanted with John, which was unbelievably fun. It was a great time for me. We loved it.

STEREOGUM: It shows. I haven't actually watched the move in quite a while to be honest, but that soundtrack was literally part of the everyday soundtrack to my life during that time. Everybody I knew had it. It was one of those things that you played it a party and people would be like, "What is this?" It had a weird life of its own separate from the movie, too. Did that surprise you?

BARLOW: Harmony and Larry, from the very beginning, kind of knew what they wanted. Like I said, before the movie was shot, when they were just casting it, they said, "We want to make a movie. We want the soundtrack to have Slint in it and we want it to have Daniel Johnston." They had these ideas of other things that they were going to mix in with what we made and I was like, "Yeah, great. That's a great Slint song and it's amazing to put Daniel Johnston on there." They really had a vision from the beginning about the film and what they wanted to do. They were just flat-out like, "We want to make a shocking film. We want to make something that makes people really uncomfortable." That was their mission from the very beginning. They started showing me the very first things they had filmed, and it's part of the opening scene of the movie -- there's this very young kid making out with a girl. Larry was very very proud of the fact that that was actually the first time that that kid had ever kissed a girl. He was like, "That's the first time he's ever done this!" We were like, "Jesus."

STEREOGUM: I remember hearing that story. It's still a pretty shocking movie. Did you ever have any reservations about it? Did it ever feel like a weird thing to be a part of once you realized it was really going to push people's buttons in a crazy way?

BARLOW: I think part of the reason that Harmony Korine was attracted to my stuff was because my early work definitely has that same spirit. It definitely has a "push the envelope" spirit about it. That was part of the way that I approached music for a long time. Early on I really liked the idea of being confrontational. I loved the idea of making songs that made people really uncomfortable. I related to that. Having said that, I remember the premiere for the movie in Boston. John and I went, and our parents came to Boston, and we sat in the [same] row with them. The movie opens up with some 12-year-old smoking pot and having sex, and we were both like, OK, this is what we're in for ... Larry and Harmony are both real instigators. When I first came to New York, they took it upon themselves to show me around and they were just such wild guys. They knew no law. They were just walking into traffic in New York like people do and smoking weed on the street. Harmony had a bunch of those snappers -- those little gunpowder things you could throw -- and he'd just throw them at people. We're walking around and they're strutting through the street like Larry and Harmony -- like they own the place. They're like, "This film is going to win an Academy Award!" And this is before they even shot it. They're like, "This going to win an Oscar! We're going to walk down the carpet to accept our award to 'Good Morning, Captain' by Slint!" They just had that vision. What do you call it? The Secret? You know, the Oprah thing? They were like, "We are succeeding and this is what is going to happen!" They were so brash about it. We're walking down the street, Harmony's throwing these poppers at cops and really old ladies, and I'm like, "Jesus!" I'm running in their wake, literally just stumbling behind them as they just strut through the streets of New York into a sushi dinner that cost $400. This was a different scene for me. I was kind of stunned. Those guys were on a mission.

STEREOGUM: Did the success of the soundtrack change anything for you? Did you have new audience after "Natural One" started airing on MTV?

BARLOW: Not really. It was pretty anonymous. The success of that song was totally random. We had a video that was on MTV, but then at the same time there was a Rolling Stone article that came out on the heels of it that was like, "Hit singles that don't sell!" There was a picture of a pile of those cassette singles they used to make and right on top of the pile was "Natural One." Basically, "Natural One" was pitched to radio stations by a very shrewd ... what do you call it? Radio programmer? Promoter guy? Anyway, it was pushed by a major label through the channels of this weird glad-handing system to get the song on the radio. I don't mean to diminish the success of the song, but it was very anonymous. I just went on about my business and finished the Sebadoh record, and then Folk Implosion went into a studio and did another record. Then, we went on to make a record after that that completely flopped. Nothing really changed. John was very concerned that maybe we'd become famous or something. He thought that he wouldn't be able to walk down the street. I'm like, "Dude, you know, this song is very, very anonymous. Nobody cares what we look like." The people who liked the song don't care what we look like, and we're not going to go on tour with White Zombie, and we're not going to become famous ... We aren't going to do any of these things. We're not going to become a real band because the song is a hit. We're going to just make our little records ourselves and just continue doing what we were always doing despite all of this."

STEREOGUM: There were a lot of people that had never heard of Daniel Johnston before buying the Kids soundtrack. You guys were really doing God's work by helping bring him to a bigger audience.

BARLOW: That's true. That was really cool.

STEREOGUM: The 20-year factor does feel kind of crazy, because I was in college at the time. It is hard for me to separate my nostalgia for that period of my life from how I feel about the record. That being said, it is a really good record. Unlike a lot of movie soundtracks, Kids is a really good album.

BARLOW: I was really proud of what we did. We recorded that stuff lo-fi on cassette, but that kind of texture sounded great in a movie theater. Things have changed quite a bit as far as the way people use low-fidelity recordings in movies and stuff. Back then, when I saw the film, it still felt kind of unbelievable. I remember seeing the movie and thinking, "You know what? This works. It's cool." I was psyched. I mean, these were things I had made on little shitty portable tape recorders. One of the pieces -- I think it was "Raise The Bells" -- I made it on the portable tape recorders that I found in my parents' house, using a very cheap keyboard, and it sounded awesome. I was really pleased. It's funny too, because everything did just get back to normal after that. I was never asked to score another film or make another soundtrack. Nothing like that ever happened. It wasn't my "in" to the world of scoring films or anything. I was never asked to do it again.

STEREOGUM: That's really surprising to me. I feel like that soundtrack gets referenced all the time among film people I know.

BARLOW: I don't know. The thing with the Folk Implosion ... I mean, we did a record after that, and we finally signed to a major label on the back of "Natural One." We really knuckled down and did this real pretty big-production record, but we did it really organically in regular studios, but that record totally tanked. I hear people telling me a lot that the production of that particular record -- One Part Lullaby -- really influenced them. I'm like, "What? We were dropped from the label after that!" That was the last time that I've ever been given a budget to make a record. There was a Folk Implosion record after that I'd done without John, but that tanked too. Still to this day I have never been handed a real budget to do a record.

STEREOGUM: Oh man. That is ... such a bummer, actually.

BARLOW: One Part Lullaby. It was our big major-label record. People reference it quite a bit, but it did absolutely nothing. It's like the Kids soundtrack. It did nothing. It didn't start anything for me. It was all just back to the road after that, back to the grind of doing everything on your own, and that was it. None of these things were really a gateway to doing more film work, which would be great. It would be great to be able to do something like that again, but I've never, ever ... I'm not joking. No one ever asks.