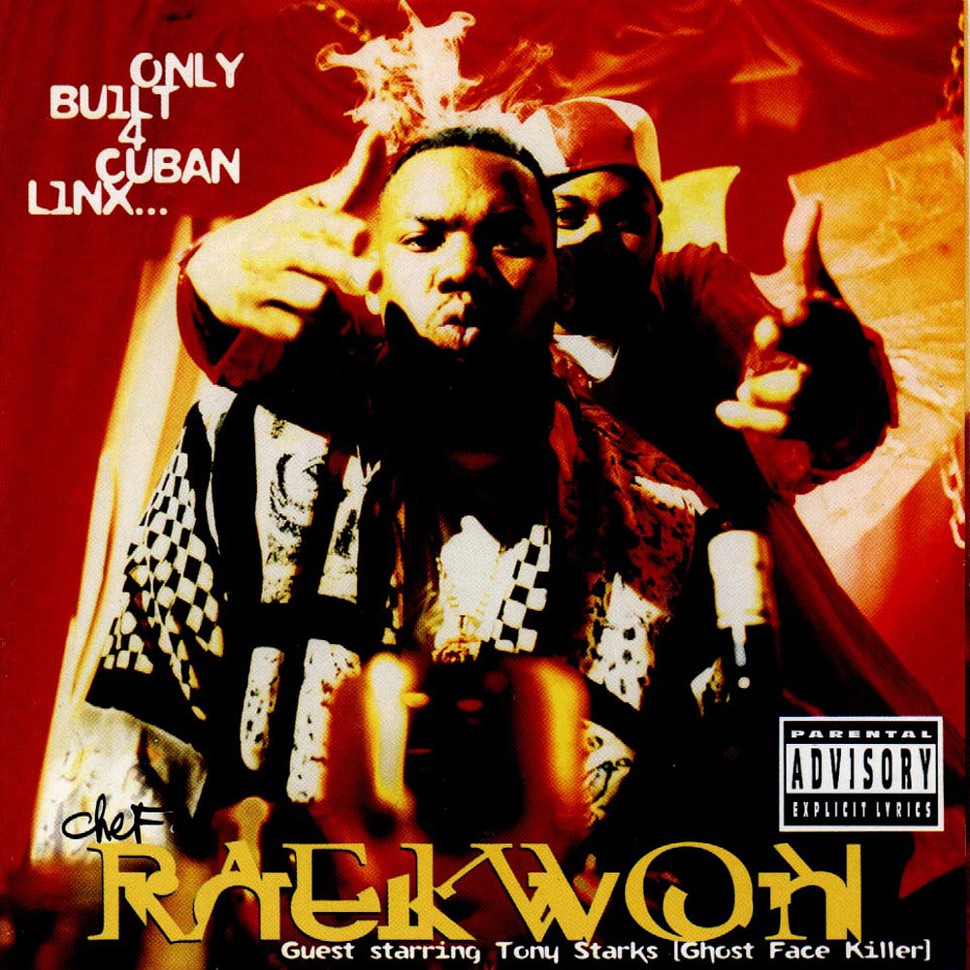

At this past year's Coachella festival, Raekwon and Ghostface Killah, the only heritage rappers on the whole weekend's bill, came out to a loud mid-afternoon reception on one of the two main stages. But when they told the crowd that they'd be performing all of Rae's 1995 album Only Built 4 Cuban Linx, I don't think they got the response they wanted. (They didn't end up doing the entire album, though they did do 10 songs from it.) Cuban Linx is a canonical work, the sort of album you need to know backwards and forwards if you want to call yourself a rap nerd. It's a crucial chapter in the entire Wu-Tang myth, and it reshaped the way people rapped about criminal enterprise. But Coachella is one big weekend-bender party, and Cuban Linx is not a party album. It's not even a live-performance album, really.

There are bangers on Cuban Linx, like "Incarcerated Scarfaces" and "Criminology," and borderline hits, like "Ice Cream." But if you play these songs on a loud enough sound system, with the two guys who rapped these songs rapping them at you, they tend do evaporate into the air. Instead, Cuban Linx is a solitary album, a headphones album. To experience it right, you have to get into the right cluttered headspace, ready to lose yourself in dense and tangled wordplay and eerie beat-construction. People still refer to Cuban Linx as the "Purple Tape." That's because Raekwon insisted that the cassette copy be made out of a distinctive purple plastic, using the rationale that drug dealers would mark their best product by tagging their bags distinctively. But the CD jewel case was also purple, and nobody ever calls it the "Purple CD." Instead, this was an album made to be heard on Walkman headphones, with the words coming through those fuzzy headphones and bouncing around in your brain, the tape hiss thickening the low end and blunting the production's sharper edges.

The Wu-Tang Clan were still a mysterious and shadowy force in 1995, an endlessly compelling cult phenomenon that had nonetheless produced, like, one and a half pop stars. After the group's debut album Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) blew the doors open, the different members of the group, one by one, started to release solo albums. Because of some canny contract manipulation from crew leader RZA, each one of the crew's nine members got to sign his own solo-release deal, which meant the different rappers were scattered across different record labels. This would eventually lead to the group's undoing, as competing managers and old resentments and internal competition led the group to become more a loose confederation of solo artists, one that occasionally gets back together to put together a contentious whole-crew album. But they were still this fascinating and varied phenomenon all the way through their initial run of solo albums, which marks one of the more bulletproof creative runs in rap history.

Method Man was the group's designated outsized cartoon-character star, the only guy on the first album who got a song to himself, so he was naturally up first. Tical, his debut, was raw and sloppy, but it had singles, including "You're All I Need," which Puff Daddy remixed into a Mary J. Blige duet, turning it into a definitive mid-'90s summer jam. Then came Ol' Dirty Bastard, whose Return To The 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version was an incoherent mess, an album I've never managed to listen to end-to-end despite multiple tries. (Lots of people love that album. Maybe my tolerance for garbled howling is just low.) But even if Return didn't work as an album, it was a masterful piece of persona-projection, and it succeeded in convincing the world that Dirty was the group's drunken, explosive, excitably rambling soul. Also, it had "Shimmy Shimmy Ya," and I'm not sure there's ever been a song that was more fun to rap along to. The different members of the group would show up on these albums, guest verses that worked like Avengers-movie cameos, suggesting things that would come along later, and RZA used them to show off different sides of his production style. The plan was working.

Considering that Wu was, by summer '95, in the business of making pop stars, Raekwon was a surprising choice for next guy up. He didn't look like a star: Short, portly, messed-up teeth. And he didn't rap like one either, delivering dense and allusive verses in a hard, marbled monotone and daring you to figure out what the hell he was talking about. But Rae had the sort of intricate, intuitively detailed rapping style that other rappers tend to love. And he had personality; his memoir-of-a-street-kid verse on "C.R.E.A.M." was tremendously important in introducing the group to the world. He and best rapping friend Ghostface Killah actually cared deeply about how they dressed and presented themselves to the world, which wasn't exactly a paramount concern within the rest of the group. And he had vision. Cuban Linx wasn't just a collection of potential singles, or a way of throwing the Rae persona out into the world. Instead, it was a deep-immersion experience.

Together, Rae and RZA concocted a loose narrative, coming up with a whole arc about Rae and the other rappers on the album as criminals looking for a way out of the grind. (U-God raps on album opener "Knuckleheadz" and then never returns. RZA explains that the idea was for U-God's character to die in the heist described early on the album, even if he really only had one verse because he'd violated his parole and only had time to record one before being sent back to prison.) And RZA had realized that Rae and Ghostface had an uncommon on-record chemistry. So Ghost shows up on nearly every track, he and Rae trading verses and adding colors and shadows to each other's narratives. Throughout, RZA adds samples from the great John Woo Hong Kong shoot-'em-up The Killer, claiming that the relationship of Rae and Ghost, kids from opposing projects in Staten Island, reminded him of the relationship between Chow Yun-Fat's principled hitman and Danny Lee's rogue cop. (A flattered Woo reportedly charged RZA nothing for the use of those samples.)

In this great XXL oral history of Cuban Linx, RZA says that he pretty much missed the initial wave of Wu-Tang's fame because he was in his dank basement studio the whole time, putting together Cuban Linx and GZA's Liquid Swords. He could've been out partying and spending money, but instead he was holed up, eating turkey burgers for dinner every night and figuring out ways to further distill his broken, eerie, minor-key sound. The tracks on Cuban Linx sound fundamentally wrong, and that's entirely intentional. Those half-buried horn stabs and detuned pianos and icepick-jab drums create a whole sonic universe, a musical reflection of the treacherous underworld depicted in the lyrics. Rae was sometimes coked-up when he came up with his lyrics, and Ghost was usually drunk on Ballantine ale when he recorded his. But both were constantly pushing themselves and each other. Wu-Tang's whole friendly-competition internal dynamic worked wonders for the album, as the different members of the group went up against each other for the limited number of guest spots. Cappadonna, a gifted Staten Island hardhead who was in prison during the Enter The Wu-Tang era, entered the group's extended circle and guaranteed his own immortality when he chivalrously offered, "I love you like I love my dick size." On "Verbal Intercourse," Nas became the first non-Wu rapper to rap on a Wu-Tang track, contributing a dazzling verse that proved how much sense he made alongside this crew.

But this wasn't a group effort. It was two guys, Rae and Ghost, trading lines back and forth. Despite Wu's rising profile, they never went out of their way to be inviting. Instead, they went the other way, developing this whole insular rap language that, if you were a white suburban teenager, made no sense initially but still had its own weight and logic. You'd listen all day, trying to figure out way, say, "slang-rap democracy" meant -- if it even meant anything rather than just being a bunch of words that sounded cool together. Wu-Tang's mystique was already thick before Cuban Linx, but after the album landed, it became practically impenetrable, which of course made it more interesting.

Raekwon likes to brag about the trends he started with Cuban Linx, but the things he mentions were mostly shallow: The practice of constantly coming up with new mafioso nicknames, the Cristal fixation. But the album was tremendously important anyway because of the way it talked about crime. There had been plenty of rap about crime before Cuban Linx, but most of it was rendered in broad strokes: Gun battles, death threats, run-up-in-your-house stuff. Rae and Ghost were dealing with the intricacies of the drug trade, the fear and anxiety and the weird codes of etiquette that outsiders can never decipher. They'd talk about specific geography, about finding new connects, about the petty resentments that can lead to death. After Cuban Linx, you couldn't just rap about being a criminal; you had to add all the little storytelling details that let the world know you'd actually been there. Jay-Z would run with that a year later on Reasonable Doubt, and Young Jeezy would run with it a decade later on Let's Get It: Thug Motivation 101. It's still there. You still need to rap like you know what you're talking about.

More than a way forward, though, Cuban Linx represented a peak, the moment when everything came together for Wu-Tang. It's not my favorite of that first wave of Wu-Tang solo albums; for sheer energy and emotion, that's still Ghostface's Ironman. But Cuban Linx is the most beloved of that run, and I understand why. After Cuban Linx, it was impossible to hear RZA as anything but an auteur, a musician who translated New York boom-bap into sinister cinema. It also built on the foundation of the other great New York rap full-lengths that were coming out around the time -- Illmatic, The Infamous, Ready To Die -- hanging with them in ways that no other Wu-Tang album had managed. It represented a moment when New York rap was hard and weird and uncompromising and popular. Cuban Linx never had a huge single, but it still sold a million copies and led to a spike in babies being named "Raekwon." It resonated. Now, some videos: