In 1963, American International Pictures released the first of the Beach Party movies, a series of films targeted toward teen audiences at a time when the concept of young adulthood was still half-rendered. Every one of them stars Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello, and every one takes place on or near a sunny beach in Southern California or some other hip and idyllic location. The plot is always scaffolded as follows: a group of teens go to a beach-like destination and are instantly misunderstood by the surrounding adults who consider them delinquents and attempt to foil their vacationing fun. Surfing, drag racing, motorcycle gangs, skateboarding, whatever recreational activities were in vogue at the time, are on display, alongside the outfits and up-dos. Though the narrative arc never changes, the most original element of each film comes in the shape of its musical score and soundtrack. There is always a musical performance or two, a stray character made to imitate a pop-culture icon of the era. Stevie Wonder, Dick Dale, the surf rock band the Hondells, Nancy Sinatra, James Brown, Lesley Gore, and the Supremes all made appearances. They're unmistakable B-movies, bad objects made for a drive-thru theater that have ended up in the arsenal of film history because AIP managed to do one thing extraordinarily well: bottle up the passing fads of an era to be dug up and perused decades later. They also made a lot of money because they gave teenage audiences across the country a glimpse of the look and sound of cutting-edge coolness.

In the tradition of Beach Party, We Are Your Friends -- the directorial debut from Max Joseph (of Catfish fame) -- is not a movie made for posterity. Even its title, co-opted from Justice's remix of Simian's "Never Be Alone," already sounds dated. Structurally, it's a much more narratively sound film than any of the Beach Party classics; it's a coming-of-age tale, a hero's journey, that follows a group of 20-something men born and raised in the San Fernando Valley who promote parties in the certifiably trendy L.A. neighborhood of Silver Lake. It's an aspirational story about a group of working-class kids who have been worn down by a shitty economy and are all too aware of the fact that they're going nowhere and are hustling in all the wrong places to try and change that. Cole Carter (played by Zac Efron) lives with his best friend and kinda-sorta manager, the tweaky, crazy-eyed Mason, who gets Cole booked to DJ parties by being a somewhat charming, fast-talking asshole. Each character in the film undergoes a transformation of sorts, and there is at least one sad scene, but any film that builds its identity around a very specific contemporary musical moment is doomed to be labeled an artifact the minute it's out of theaters. That, and the throngs of people who consider themselves a part of the still-growing and changing musical scene are inevitably going to push back on a major studio's portrayal of their community. Big-budget EDM as a generalized blanket genre is entirely built on a culture of "community." It's globalized and all-inclusive because all it depends on to sustain itself is a fanbase willing to spend an inordinate amount of money on festival tickets. You don't need to have a shared past or a common language to gyrate and fist-pump; the bass drop is universal.

This interconnectivity is painstakingly explained during one of the most pivotal scenes in We Are Your Friends, when Cole Carter mansplains the delicate art of DJing to his love interest, Sophie. The explanation is a laundry list of facts, namely the BPM of different forms of dance music. This how-to-be-a-DJ description is featured prominently in the trailer, and it's one of many unintentionally laughable bits of dialogue found throughout that proves screenwriter Meaghan Oppenheimer and Joseph earnestly wanted this to be a movie about music, or at least, about the way that music makes us relate to other people, and to our immediate surroundings. We watch Cole painstakingly drag clips of audio around on Ableton-esque software, repeatedly pitch-shifting the same crappy sample. Later, Cole's main adviser, the alcoholic once-great-DJ James, shows his protégé the impressive home-recording studio in his Hollywood basement. Cole gasps when he sees the room and exclaims in a cringe-inducing try-too-hard moment: "You have a Wurlitzer?!" And then, in what should henceforth be known as the Analog 101 Lecture Scene, James explains to Cole that "sounds have souls" and just because electronic music is played off of a laptop, doesn't mean that samples are all synthetically produced. Cole's eyes visibly widen as James scurries around his studio playing real-life instruments, explaining that the sounds of the universe can fit into one crappy laptop if Cole focuses on innovating his production sound in order to avoid imitation. James also warns Cole against trying to sound like "Skrillex's brother."

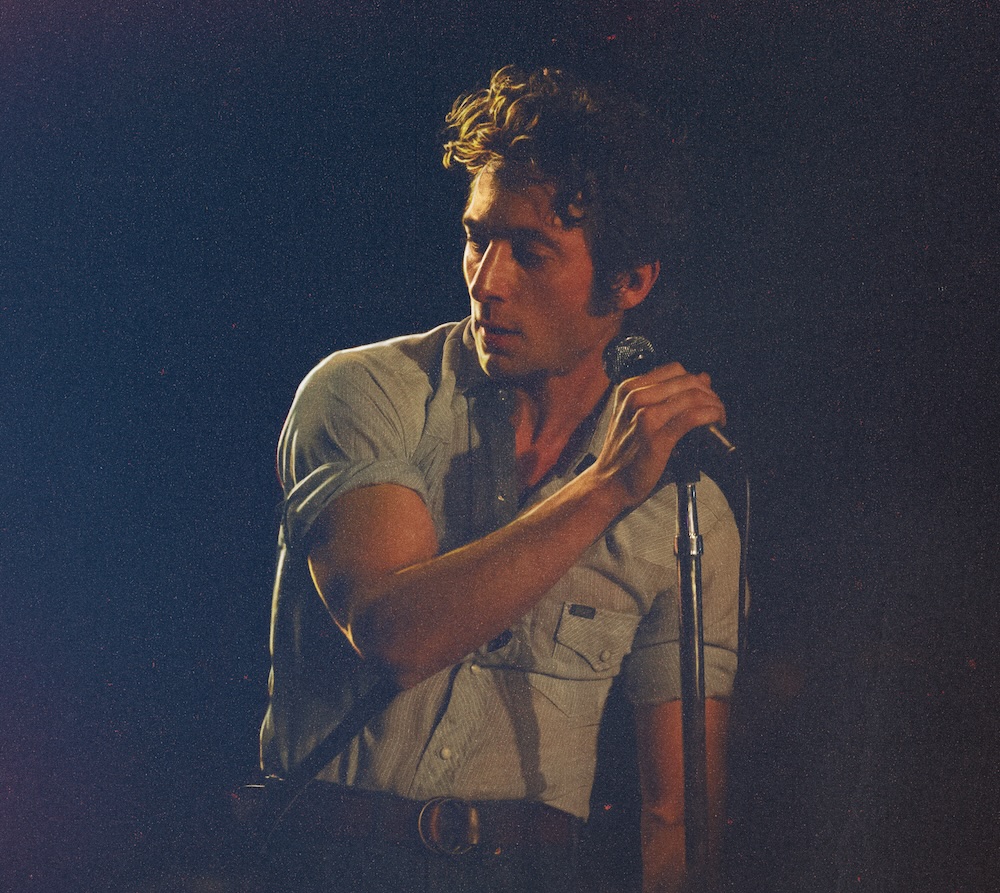

That scene will remind anyone with a basic understanding of electronic music-making what this movie is: a movie for people who don't know anything about electronic music-making. (Which begs the obvious question: If people who genuinely love this culture aren't going to want to see this movie, then who is?) This is a Warner Bros. picture starring Zac Efron, the dude from High School Musical who proved himself to be a conventionally attractive grown male when he graced the cover of Rolling Stone back in 2007. I remember it well, because I couldn't help but drool a little bit in my half-assed goth costume (read: lots of eyeliner, studded belt) when the issue arrived in my mailbox. Fans of Efron's (perfect) biceps will love We Are Your Friends because there's only a handful of scenes in which Efron wears an actual shirt, a welcome byproduct of his San Fernando Valley-boy aesthetic.

Efron's look is important, because he and all of his surrounding friends and followers do an immaculate job portraying an outsider's view of mainstream EDM culture in all of its broed-out glory. As someone who doesn't have personal stakes in the scene, this doesn't bother me. I expect the muscle-tees, the copious drug consumption, and the rampant misogyny from a movie about a partying culture that doesn't represent my ideals. But it's problematic when a movie infiltrates a culture and doesn't even try to counteract negative stereotypes about it. One of the first things we hear in Efron's voice-over narration is an introduction to the Valley, known for its porn industry and "ditzy girls." (Note that Efron's love interest, Sophie, is not a ditz because she went to Stanford.) This is both good and bad; on one hand, if the characters in We Are Your Friends weren't semi-losers who only talk about women in the context of sex, I would feel like I'd been catfished into seeing this film (haaaa). On the other hand, any fans who don't take drugs (they exist!) will be crushed to see how much each of the characters live up to misperceptions.

That being said, nothing about We Are Your Friends is so outwardly offensive or frustrating to the point that it will send people storming out of the theater, and despite its predictable plotline, it's rarely boring. We Are Your Friends is edited to mirror its soundtrack, each scene drags on just long enough to cut at the warble that precedes a bass drop, and though party scenes abound, they're always pointed. Those scenes propel the plot forward and are soundtracked by the most memorable songs. Cole and Sophie share their first kiss at Vegas' Electric Daisy Carnival (EDC) to a remix of Years & Years' "Desire." When James drags Cole to ogle strippers on a rough drunken night, "I Like Tuh" plays in the background. The score that accompanied the soundtrack was produced by Segal, who is best known for his work on the UK version of Skins, which is fitting. His is the stuff that makes surround-sound systems shake, and We Are Your Friends does just as good of a job as that TV show does at making cinematic hedonism look like a lot of fun until it's not.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Regardless of how plainly tolerable the soundtrack is, everything about We Are Your Friends is so of-this-moment that its most purposefully winking one-liners are fated to read as empty statements in fewer than 10 years. It already feels late when the 30-plus-year-old James suggests that Cole should "slap a hashtag" on a snarky comment. When I wrote about Clueless for its 20-year anniversary back in July, I talked about how films made for teens are ephemeral by default, because writers and directors will always feel pressure to make every aspect of them as contemporary and immediate as possible. Clueless survived because it's self-aware, but We Are Your Friends doesn't have any of the same wit or hindsight. Mainstream EDM is still growing into something astronomically bigger than it was when We Are Your Friends was in pre-production. The impulse behind We Are Your Friends isn't wholly unlike Cameron Crowe's romantic comedy Singles, which was set in Seattle in 1992 and featured a soundtrack dominated by popular grunge bands. But unlike Singles, the community displayed in We Are Your Friends isn't an emerging subculture: It's a multi-million dollar industry.

This distinction matters, because there will be voices arguing that We Are Your Friends is exploiting a community, that it's infiltrating a small and sacred PLUR mentality and oversimplifying it. But the version of "EDM" depicted in the film isn't a subculture, it's a mainstream music trend that's far less novel than the movie makes it out to be. It's also, from Cole's perspective, a genre that produces an enviable cash flow. In one of the early scenes in the film, Cole explains away any potential complexities that come with trying to make it in the EDM industry and says: "All you need is a laptop, some talent, and one track." (In the case of this film, it takes that, and a ton of support from an already established, loaded producer). We Are Your Friends already feels like a relic; a romanticized, long-since-passed opportunity to cash in on a highly-marketable contemporary moment in pop culture before it fizzles out or balloons into something more ubiquitous than it already is.