Blur had arrived. They had achieved what they had set out to do. After the disillusioning experience of being partially forced into a set of already-dying English trends with their 1991 debut Leisure and the miserable U.S. tour that followed, Damon Albarn had become possessed in an effort to find some new sound, some assertion of contemporary Britishness. And they'd succeeded with 1993's Modern Life Is Rubbish, but true stardom eluded them until Parklife followed in 1994. That's when Blur solidified their footing as the Blur we know now: massive pop success in their native England, voice-of-a-generation kind of stature. After an album like Parklife, an album that offered up an overflowing, multi-faceted vision of English life that ran the spectrum from caustic to melancholic, where could Blur go next? In hindsight, it might've been the moment where, in terms of legacy and critical standing, it would've been time to abandon the form and content they'd already perfected. But there were circumstances at the time: Why leave behind the idiosyncratic voice and sound that had brought you to that moment? How could you realize, if you're in the center of the Britpop maelstrom, that you might have tapped out your ability to approach that material in the same way? Blur didn't abandon Britpop then, not yet. They doubled down with 1995's The Great Escape, the capstone to the arc that began with Modern Life Is Rubbish just two years earlier.

The Great Escape is an odd chapter in a career that would essentially progress in a continuing series of odd chapters from that point on. This is the moment that Britpop was reaching its zenith, at least in terms of the popularity and output of its primary figures. But The Great Escape also marks the moment where Blur themselves truly pushed the Britpop aesthetic and ethos about as far as they could. Modern Life, Parklife, and The Great Escape -- the three albums that comprise Blur's "Life" trilogy, or the Britpop trilogy -- all have their own specific qualities. As assertive a manifesto as Modern Life is, it also possesses the kind of faint murk of a grey afternoon; it was sprawling and ambitious to a ludicrous extent considering it was the answer to Leisure's near-total lack of individual identity, but it was also despondent, a tendency to shoegaze still lingering in "Blue Jeans," "Oily Water," or especially the gorgeously heartbreaking closer "Resigned." Parklife, in comparison, picked up the themes and imagery of '90s Britain and made it sharper, more vivid, like color flushing its way into a black-and-white film and lighting up all the corners of life you hadn't noticed before. Thematically speaking, The Great Escape continued apace, detailing the inertia or apathy of a certain kind of well-off British suburban life. While it's sonically of a piece with its predecessors, the way its tone differed, pretty inevitably, also meant it'd be one of conclusion. Here, Blur blew out everything they'd explored already into sounds and stories that were nauseatingly pretty in their over-orchestration, but also uglier in the seediness gurgling its way out to the surface of upper middle-class comfort. Over the course of The Great Escape, Blur offered up densely arranged pop that relayed their most cynical outlooks, crafting an album that was at once their most ridiculously overwrought, occasionally their most bitingly incisive, and also boasting some of the most achingly beautiful and yearning moments in their catalog.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Outside of Blur's own songwriting, though, The Great Escape hit at the feverish breaking point of Britpop. This was the same year Pulp would release Different Class; Oasis' What's The Story (Morning Glory)? would follow The Great Escape by less than a month. This was the year where the British media pit Oasis and Blur against one another in the so-called "Battle Of Britpop," the race to see who would have a more successful single after Blur's label Food Records moved "Country House" up a week to be released on the same day as "Roll With It," incensing Noel Gallagher. To speak with the stereotypes that are usually employed to sum this up: It was the Northerner classic rockers with "Roll With It" vs. the artier London group with "Country House." All the shit-talking in the British press, the archetypal Britpop argument of Oasis or Blur -- that stuff is rooted in this moment in the Britpop narrative. And the way the story goes is that Blur won -- "Country House" sat at #1 ahead of "Roll With It" at #2 -- but lost both their critical and popular standing when Morning Glory came out and became one of the highest-selling albums of all time in Britain. Oasis went on to become stratospheric superstars; Blur went onto remain more artistically vital and upend much of their sound and identity as a band in the latter half of the '90s. In hindsight, 1995 was both the peak and the end of something, the moment before all these bands scattered and wound up making wounded detours after becoming wildly famous in the thick of the Britpop rush.

Listening back to The Great Escape with knowledge of how the subsequent two decades played out for Blur and Albarn, the writing is on the wall. By the time you get here, the panoramic tales of Parklife have festered and resulted into mutant tales of dejection. The social commentary Blur had offered up on the two preceding records became hyperreal here, but also more depressive -- which is saying something coming off a record like Parklife, which could be acerbic throughout and then have something as gut-wrenching as "This Is A Low" at its conclusion. While much of Blur's "Life" trilogy parsed the long reckoning with post-empire British identity and '90s suburban ennui, the lyrics and instrumentation of The Great Escape offered an increasingly bleaker, more twisted take that surreptitiously set the tone for the fuzzed- and freaked-out self-titled LP in 1997 and the beleaguered 13 in 1999. Though "Country House" is one of the band's more cartoonish singles, it has some of the most telling lines on the album. Albarn sings "I'm a professional cynic, but my heart's not in it" and mentions being "Caught up in a century's anxiety." They'd already written a song called "End Of A Century," but the sense of a paradigm shift approaching -- and that it was approaching while people lived in a kind of bloated malaise -- runs through the entirety of The Great Escape. This time around, the social observations portray the sort of weathered and bored opulence that comes at the end of times, or at least the end of some kind of times.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

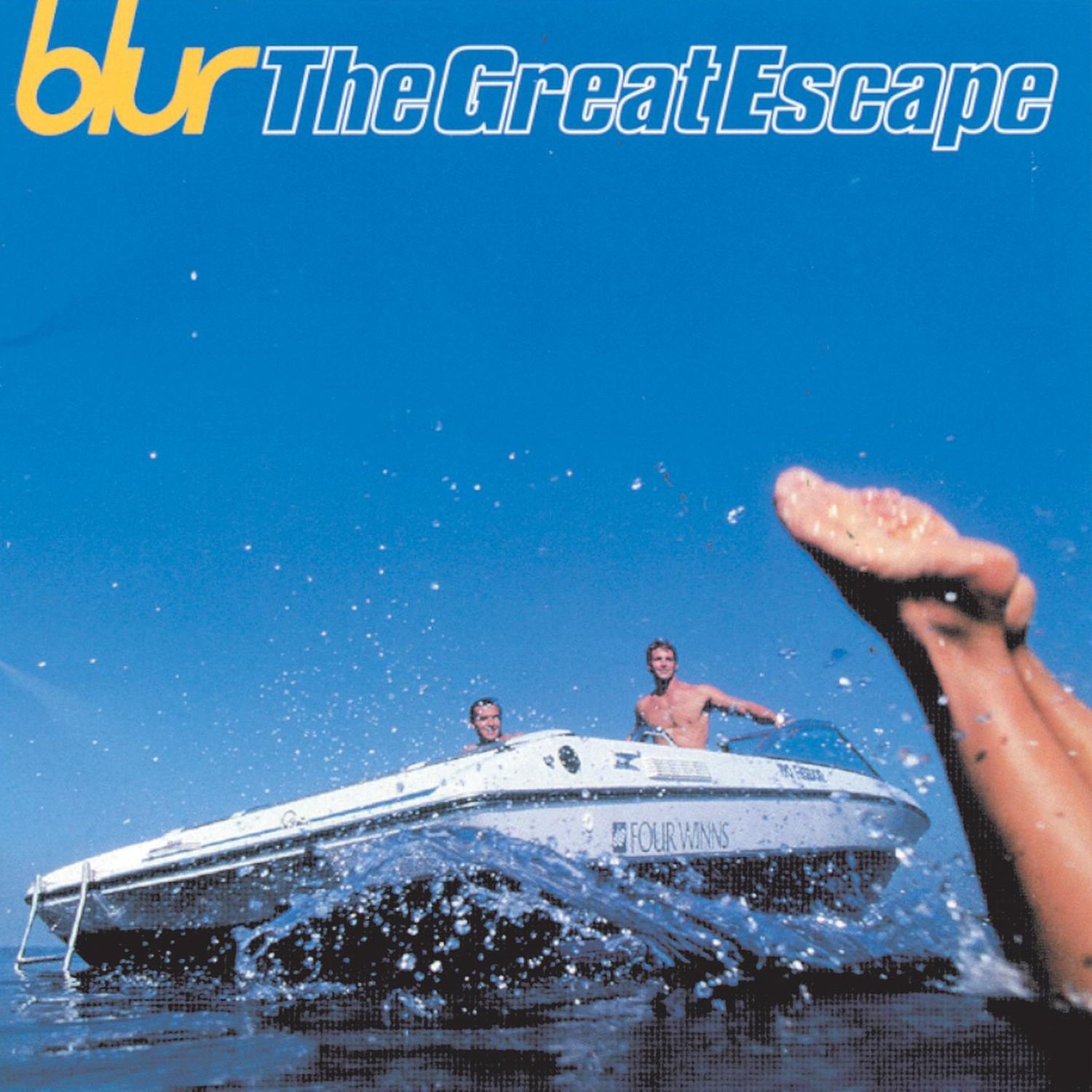

The whole ethos of The Great Escape approaches some kind of acidic Pop Art, from the vacation-brochure cover art to the decadence of the guitars and synths that open the album in "Stereotypes." There's a certain embrace of decadence in general -- or, if not an embrace, a willful immersion in it. Blame it on his experience with celebrity or blame it on whatever, but Albarn's interpretation of the end of the century this time is usually translated in feelings of detachment and alienation. On The Great Escape, that alternates between vignettes about the wealthy as well as the solidly middle class toiling away in dead-end suburban lives. Right after those almost-sleazy opening notes to "Stereotypes" comes the opening salvo of the album ("The suburbs they are dreaming, they are a twinkle in her eye") leading up to the proclamation that "Wife-swapping is the future" and tales of the protagonist watching sex tapes of herself. But it's all conveyed in the same way as so much of the rest of the album. You picture these characters -- Ernold Same, Dan Abnormal, Yuko & Hiro, the Charmless Man, the man with the Country House -- proceeding through lives of some level of comfort or wealth with flat, zombie-eyed affect. With Blur situating all of that in what is perhaps their most lavish production and instrumentation, the end result is some kind of grossly psychedelic or phantasmagoric vision of consumerism and rote daily routine.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Where Parklife had a frenetic, electric energy underlying even its most biting observations, there is a wearied weight to its successor. The way Albarn depicts everything here is in the vein of a lackadaisical kind of affluence, as if wanting to ask the question "Is that all there is?" but being too apathetic to muster the energy. The professional cynic voices that over and over: "Other people turn around and laugh at you/ If you say these are the best days of our lives" in "Best Days," "They stumbled into their lives/ In a vague way became man and wife" in "Fade Away," the sneer behind the character portraits in "Country House" and "Charmless Man." It's a specific kind of disenchantment, a loneliness and alienation amidst the brightest colors possible. Every now and then, the dark heart of the album exposes itself more explicitly, like in two of the band's finest deep cuts, "He Thought Of Cars" and "Entertain Me." The former's rhythm works in a sickly push-pull inertia as Albarn sings "He thought of cars and where, where to drive them/ Who to drive them with/ There, there was no one"; the latter is some kind of deluded dance track where he employs an android drawl to repeatedly demand "Entertain me." The over-the-top nature of all the music, the way the lyrics paint a world of pointless comfort in an advertising-ridden world -- collectively, these elements of The Great Escape approach a dystopian vision of a culture full of people who have what they want, and still want more, or don't know how to otherwise fill the still-extant void. Hiro drinks in the evening because it helps with relaxing; Hiro can't sleep without drinking.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

The crown jewel of The Great Escape is "The Universal." The track is quite possibly Blur's absolute finest, and it's also in a way the moment where everything about the album coalesces together. With its undulating guitar figure, massive string swells, and desperately open-hearted chorus, it's easily one of the most aesthetically pretty songs the band ever recorded, and easily one of their most wondrous and yearning. At the same time it feels like it could soundtrack a euphoric movie credits sequence, though, it also sounds like it could soundtrack some kind of mental breakdown. It's one of those perfect songs that can sound incredibly joyous or incredibly tragic depending on how you approach it. Its famous Jonathan Glazer-helmed video referenced Kubrick's adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, with Blur dressed up in Droog outfits in some kind of cleanly dystopian milk bar. The contrast underlines the loopy funhouse mirror projection of modern life that dominates The Great Escape as a whole. It's some of their most glistening, produced surfaces, leading the way down into the depths of some of their grisliest interactions with soul-crushing daily minutia. When the band play "The Universal" now, it's divorced from all that. It's simply the transportive classic saved for the end of the set. It's transportive on the album, too, it's just a question as to where. Maybe it's the transcendent escape from the world sketched out across The Great Escape; maybe it's the real escape. Or, maybe it's the same escape the title talks about -- the further descent into a repetitively sugary life, a further escape from self-evaluation amidst that end-of-the-century life.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Though it was rapturously received upon its release, The Great Escape is often slighted as one of the weaker entries in Blur's catalog. Sometimes that's hard to argue with, considering the highs that came before, and the radical, successful departures that followed. The band themselves have disowned it in ways, whether it's Albarn writing it off as messy (and aligning it with Leisure as one of the two bad albums he'd made as of 2007) or the various band members regularly recalling the fraying-at-the-edges experience of their lives at that point. And sure, it's uneven, but it's also potentially the most interesting record in a career that's basically wall-to-wall with records that are very interesting for very different reasons. It might've been the first bit of the Britpop bubble bursting, unseen at first, setting the stage for the big comedown through what was left of the 20th century. It's the excessive conclusion to one strand of the Britpop tale, to Blur's story within that larger framework. How could it be anything else? They already pushed this further than it arguably should or could have been pushed after Parklife; the deeper and darker things were seeping in and leading the band towards a sweetly haunting brand of pop music. From here, all they could do was embrace those darker impulses musically, too, whether with Blur's heroin meditation "Beetlebum" or the real-end-of-the-century gospel elegy of 13's "Tender." But to situate The Great Escape as simply an intriguing and crucial step in the band's development does it a disservice. It shouldn't be sidelined in their career. Its flaws are integral to it. There's a brilliance to big, overblown records like this, the ones that come after a band tried to grasp everything, succeeded, and then tried to grasp more. Or tried to reckon with what you do when you're in a place where you're trying to grasp more and there's simply nothing more to grasp. The Great Escape was the unavoidable final chapter to the path Blur had set themselves on with the "Life" trilogy, rendered in lurid technicolor that still, in its way, feels more like real life than a large percentage of the rest of their work. There couldn't have been a more fitting conclusion to this part of their story.